North Vietnam, officially known as the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), was a socialist state that existed from 1945 to 1976, primarily characterized by its communist political system under the leadership of the Vietnamese Workers' Party, later renamed the Communist Party of Vietnam. Founded by Ho Chi Minh, the DRV was established following Vietnam's declaration of independence from French colonial rule and was marked by its alignment with the Soviet Union and China during the Cold War. Politically, North Vietnam was a one-party state, with the Communist Party holding absolute power and implementing Marxist-Leninist ideologies, including centralized planning, collectivization of agriculture, and a focus on anti-imperialist and nationalist struggles. Its political structure was deeply intertwined with its role in the Vietnam War, where it sought to unify the country under its socialist system, ultimately achieving this goal in 1975 with the fall of South Vietnam and the reunification of Vietnam in 1976.

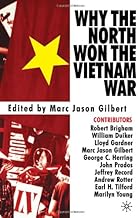

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Communist Party Dominance: One-party system led by the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV)

- Political Structure: Socialist Republic with a President, Prime Minister, and National Assembly

- Ideology: Marxism-Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought guide governance and policies

- Foreign Relations: Focus on independence, non-alignment, and strategic partnerships with global powers

- Economic Policies: State-controlled economy with Doi Moi reforms promoting market-oriented socialism

Communist Party Dominance: One-party system led by the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV)

The political landscape of North Vietnam, and subsequently unified Vietnam, is defined by the unyielding dominance of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). This one-party system, established in 1945, has been the cornerstone of the country's political structure, shaping its governance, policies, and societal norms. The CPV's control is not merely a theoretical construct but a practical reality, where the party's influence permeates every aspect of Vietnamese life.

The CPV's Monopoly on Power

In Vietnam, the CPV holds an exclusive grip on political power, a monopoly that is both constitutional and deeply ingrained in the nation's fabric. The 1992 Constitution of Vietnam explicitly states that the CPV is the "leading force of the state and society," effectively legalizing its dominant position. This one-party system means that all other political parties are prohibited, and the CPV's leadership is the ultimate authority in decision-making processes. The party's Central Committee, a powerful body comprising around 200 members, sets the country's political agenda, making it the de facto ruling organ. This committee elects the Politburo, an even more exclusive group of approximately 19 members, who hold the most significant decision-making power.

A Top-Down Governance Structure

The CPV's dominance is characterized by a highly centralized governance model. The party's leadership appoints key government officials, including the President, Prime Minister, and ministers, ensuring that its members or affiliates hold these positions. This top-down approach extends to local levels, where CPV committees oversee provincial and municipal governments, effectively controlling policy implementation and administration. The party's influence is so pervasive that it often blurs the lines between government and party functions, with CPV committees frequently making decisions that should typically fall under the purview of state institutions.

Maintaining Control: Strategies and Mechanisms

To sustain its dominance, the CPV employs various strategies. Firstly, it maintains a tight grip on media and information dissemination, ensuring that state-controlled media outlets promote the party's agenda and ideology. This control over information limits public access to alternative political narratives. Secondly, the CPV has a vast network of party members and affiliates, estimated to be over 5 million, who are strategically placed in various sectors, including government, military, and state-owned enterprises. This extensive network ensures the party's presence and influence at all levels of society. Additionally, the CPV has been adept at co-opting potential sources of opposition, often integrating influential individuals or groups into its fold, thereby neutralizing dissent.

Impact and Criticisms

The CPV's one-party rule has had significant implications for Vietnam's political and social development. On one hand, it has provided stability and a clear direction for the country's growth, particularly in the post-war reunification period. The party's focus on economic reform and development has lifted millions out of poverty. However, this dominance also raises concerns about political freedom, human rights, and the lack of democratic processes. Critics argue that the absence of political competition stifles innovation and accountability, leading to inefficiencies and corruption. The CPV's control over media and civil society limits public discourse and the ability to challenge the status quo. Despite these criticisms, the CPV's dominance remains unchallenged, and any significant political reforms would likely emerge from within the party itself.

In understanding North Vietnam's political system, it becomes evident that the CPV's one-party rule is not just a theoretical concept but a practical framework that shapes the country's governance and societal dynamics. This dominance, while providing stability, also presents challenges to democratic ideals and political diversity.

Does the Political Caucus System Truly Work for Democracy?

You may want to see also

Political Structure: Socialist Republic with a President, Prime Minister, and National Assembly

North Vietnam, officially known as the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) until 1976, was a socialist state with a distinct political structure that mirrored its ideological foundations. At its core, the DRV was a one-party system dominated by the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), which held ultimate authority over governance. This structure was characterized by a tripartite leadership model: a President, a Prime Minister, and a National Assembly. Each of these institutions played a specific role in the functioning of the state, though their powers were ultimately derived from and subordinate to the CPV.

The President of North Vietnam served as the head of state, representing the nation domestically and internationally. While the position held symbolic importance, its powers were largely ceremonial, with the President acting as a figurehead for the socialist regime. In contrast, the Prime Minister wielded significant executive authority, overseeing the government’s day-to-operations and implementing policies directed by the CPV. This division of roles ensured a balance between symbolic leadership and administrative efficiency, a common feature in socialist republics.

The National Assembly, as the legislative body, was theoretically the highest organ of state power. Composed of elected representatives, it was tasked with enacting laws, approving the state budget, and ratifying treaties. However, in practice, the Assembly’s decisions were guided by the CPV’s Central Committee, which set the political agenda. This dynamic highlights the overarching control of the Party, which ensured that all state institutions aligned with socialist principles and revolutionary goals.

A comparative analysis reveals that North Vietnam’s political structure shared similarities with other socialist states, such as the Soviet Union and China, where a single party dominated governance. However, the DRV’s model was uniquely tailored to its revolutionary context, emphasizing collective leadership and ideological purity. For instance, the President’s role was less authoritarian than in some other socialist states, reflecting the DRV’s focus on consensus-building within the Party.

In practical terms, understanding North Vietnam’s political structure requires recognizing the interplay between these institutions and the CPV’s central role. While the President, Prime Minister, and National Assembly had distinct functions, their actions were always framed within the Party’s ideological framework. This structure was designed to consolidate power, ensure stability, and advance the socialist agenda, making it a defining feature of North Vietnam’s political identity.

Navigating the Path: A Beginner's Guide to Entering Indian Politics

You may want to see also

Ideology: Marxism-Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought guide governance and policies

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), was founded on the principles of Marxism-Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought, a unique synthesis of communist ideology adapted to the Vietnamese context. This ideological framework was not merely a theoretical construct but a practical guide for governance, shaping policies in economics, social welfare, and foreign relations. At its core, Marxism-Leninism provided the DRV with a blueprint for a classless, socialist society, while Ho Chi Minh Thought infused this with nationalist aspirations and agrarian-focused strategies tailored to Vietnam’s realities.

To understand the application of this ideology, consider the land reform campaigns of the 1950s. Guided by Marxist principles of redistributing wealth from the bourgeoisie to the proletariat, the DRV confiscated land from wealthy landowners and redistributed it to peasant farmers. This policy, though rooted in Marxist theory, was executed with a distinctly Vietnamese twist: it emphasized collective farming and rural self-sufficiency, reflecting Ho Chi Minh’s emphasis on agrarian socialism. However, the campaign also highlights the challenges of ideological implementation, as it led to social unrest and economic disruptions, underscoring the tension between theory and practice.

Instructively, the DRV’s economic policies were structured around centralized planning, a hallmark of Marxist-Leninist systems. The state controlled key industries, such as agriculture, manufacturing, and trade, aiming to eliminate capitalist exploitation and ensure equitable distribution of resources. For instance, the First Five-Year Plan (1961–1965) prioritized industrialization and agricultural collectivization, mirroring Soviet models. Yet, Ho Chi Minh Thought tempered this approach by emphasizing self-reliance and local initiative, a pragmatic adaptation to Vietnam’s limited resources and geopolitical isolation. This blend of ideological rigor and contextual flexibility was critical to the DRV’s survival during the Vietnam War.

Persuasively, the DRV’s commitment to Marxism-Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought extended beyond domestic policies to its foreign relations. The ideology positioned the DRV as a vanguard of anti-imperialist struggle, aligning it with other socialist states while fostering solidarity with global liberation movements. For example, the DRV’s support for the Pathet Lao in Laos and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia was framed as a continuation of its revolutionary mission. However, this ideological alignment also constrained its diplomatic flexibility, as it often prioritized ideological purity over pragmatic alliances, particularly during the Sino-Soviet split.

Comparatively, the DRV’s ideological framework contrasts sharply with that of South Vietnam, which was aligned with Western capitalist systems. While the South embraced market-driven economics and U.S.-backed modernization, the North’s state-led, collectivist model aimed to dismantle class hierarchies and foster communal solidarity. This ideological divide was not merely economic but deeply moral, with the DRV portraying its struggle as a fight for justice against exploitation. The reunification of Vietnam in 1975 under socialist principles underscores the enduring influence of this ideology, though its practical implementation evolved significantly in the post-war era.

In conclusion, Marxism-Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought were not static doctrines but dynamic tools that shaped North Vietnam’s governance and policies. Their application reveals both the strengths of ideological clarity—such as mobilizing mass support for revolutionary goals—and the limitations of rigid frameworks in addressing complex realities. For those studying political systems, the DRV offers a case study in how ideology can be both a unifying force and a source of tension, depending on its adaptation to local conditions. Practical takeaways include the importance of balancing ideological purity with pragmatic flexibility and the need to address unintended consequences, such as those seen in the land reform campaigns.

Exploring the Length and Impact of Political Poetry Through History

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$38.95 $14.95

Foreign Relations: Focus on independence, non-alignment, and strategic partnerships with global powers

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), has historically pursued a foreign policy rooted in independence, non-alignment, and strategic partnerships with global powers. This approach, shaped by its struggle for sovereignty and the Cold War context, remains a cornerstone of its international relations.

At its core, North Vietnam's foreign policy prioritizes autonomy in decision-making. This stems from its experience as a colony and its subsequent fight for independence from France and later, its resistance to American intervention. The DRV has consistently sought to avoid becoming a pawn in the geopolitical games of major powers, instead carving out its own path on the world stage.

A key manifestation of this independence is North Vietnam's commitment to non-alignment. While it received significant support from the Soviet Union and China during the Vietnam War, the DRV carefully avoided formal alliance structures that could compromise its autonomy. This non-aligned stance allowed it to maintain a degree of flexibility in its foreign relations, engaging with both Eastern and Western blocs when it served its interests.

However, non-alignment doesn't equate to isolation. North Vietnam has strategically forged partnerships with global powers to advance its national interests. During the war, the Soviet Union and China provided crucial military and economic aid. Post-unification, Vietnam has diversified its partnerships, engaging with the United States, the European Union, and other regional powers. These partnerships are carefully calibrated, focusing on areas of mutual benefit while safeguarding Vietnam's independence.

A prime example is Vietnam's relationship with the United States. Despite their historical conflict, the two countries have normalized relations and established a comprehensive partnership. This partnership encompasses trade, investment, security cooperation, and people-to-people exchanges. Vietnam benefits from increased economic opportunities and access to technology, while the US gains a strategic partner in Southeast Asia.

North Vietnam's approach to foreign relations offers valuable lessons for other nations seeking to navigate the complexities of the international system. By prioritizing independence, embracing non-alignment, and forging strategic partnerships, countries can safeguard their sovereignty while engaging effectively with the global community. This delicate balance requires constant vigilance and adaptability, but it allows nations to chart their own course in a multipolar world.

Understanding Political Sectionalism: Causes, Impacts, and Historical Context

You may want to see also

Economic Policies: State-controlled economy with Doi Moi reforms promoting market-oriented socialism

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, emerged from decades of war with a centrally planned economy characterized by state ownership of the means of production. This system, while ensuring equitable distribution of resources, stifled economic growth and innovation. By the 1980s, the limitations of this model became starkly apparent, prompting a bold shift in economic policy.

Enter Doi Moi, a series of market-oriented reforms initiated in 1986. This marked a pivotal moment in North Vietnam's economic trajectory, introducing elements of capitalism while retaining the Communist Party's control.

Doi Moi wasn't a wholesale abandonment of socialism but a pragmatic adaptation. It aimed to harness the dynamism of market forces while maintaining the state's guiding hand.

The reforms unfolded in stages, gradually opening the economy to foreign investment, privatizing state-owned enterprises, and encouraging private entrepreneurship. Agriculture, the backbone of the economy, saw the dismantling of collective farms in favor of household-based production, significantly boosting output.

The results were transformative. Economic growth accelerated, poverty rates plummeted, and living standards improved dramatically. North Vietnam, once a war-torn nation, emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

However, Doi Moi's success wasn't without challenges. Income inequality widened, and the influx of foreign capital raised concerns about national autonomy. Balancing the benefits of market liberalization with the principles of socialist equity remains a delicate tightrope walk for the Vietnamese government.

Doi Moi serves as a compelling example of a socialist state navigating the complexities of economic modernization. It demonstrates that market mechanisms can be harnessed within a socialist framework, fostering growth while striving for social justice. The ongoing evolution of North Vietnam's economy offers valuable insights for other nations seeking to reconcile the demands of a globalized world with their unique ideological commitments.

Are New Yorkers Polite? Debunking Stereotypes About NYC Manners

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

North Vietnam, officially known as the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), was a socialist state with a one-party system led by the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). The CPV held ultimate authority, and the government operated under a Marxist-Leninist framework.

The most prominent leader was Ho Chi Minh, who served as the President and the figurehead of the Vietnamese independence movement. Other key figures included General Vo Nguyen Giap, the military commander, and Le Duan, who became the General Secretary of the CPV and played a significant role in shaping North Vietnam's policies.

North Vietnam's communist ideology led to strong ties with other socialist countries, particularly the Soviet Union and China. It received significant military and economic aid from these allies during the Vietnam War. The DRV's foreign policy was largely driven by its goal of unifying Vietnam under communist rule and resisting what it saw as American imperialism.

![The Slanted Door: Modern Vietnamese Food [A Cookbook]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91M1YXo6XWL._AC_UY218_.jpg)