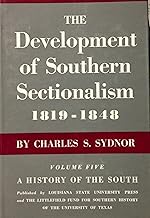

Political sectionalism refers to the division of a country or region into distinct sections, each with its own unique political, economic, and cultural interests, often leading to conflicts or tensions between these groups. This phenomenon typically arises when different regions within a nation prioritize their local concerns over national unity, resulting in competing agendas and ideologies. In the United States, for example, sectionalism was a significant factor in the 19th century, particularly between the North and the South, where disagreements over issues like slavery, tariffs, and states' rights ultimately contributed to the outbreak of the Civil War. Understanding political sectionalism is crucial for analyzing historical and contemporary political landscapes, as it highlights how regional disparities can shape national policies and social dynamics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Political sectionalism refers to the division of a country into regions with distinct political interests, often leading to conflict or competition. |

| Regional Identity | Strong identification with a specific region over national identity. |

| Economic Interests | Regions prioritize local economic agendas, often conflicting with others. |

| Cultural Differences | Variations in culture, values, and traditions across regions. |

| Political Polarization | Regions align with opposing political parties or ideologies. |

| Historical Grievances | Long-standing historical conflicts or perceived injustices between regions. |

| Resource Competition | Disputes over natural resources, funding, or infrastructure allocation. |

| Legislative Gridlock | Regional interests hinder national policy-making and compromise. |

| Secessionist Movements | Extreme cases may lead to calls for regional autonomy or independence. |

| Media Influence | Regional media outlets reinforce local perspectives, deepening divisions. |

| Electoral Patterns | Consistent voting patterns along regional lines in elections. |

| Federal vs. State Power | Tensions between centralized government and regional autonomy. |

| Social Issues | Divergent views on issues like immigration, education, and healthcare. |

| Global Examples | Observed in countries like the U.S. (North vs. South), India, and Spain. |

| Impact on Unity | Weakens national cohesion and complicates governance. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Regional Identities: How geographic areas develop distinct political cultures and loyalties within a larger nation

- Economic Interests: Divergent economic priorities among regions driving political divisions and conflicts

- Social Values: Differences in social norms, beliefs, and ideologies creating sectional political alignments

- Historical Grievances: Past events or injustices fueling ongoing regional political tensions and rivalries

- Policy Disputes: Regional disagreements over specific policies (e.g., tariffs, slavery) exacerbating sectionalism

Regional Identities: How geographic areas develop distinct political cultures and loyalties within a larger nation

Geographic regions within a nation often cultivate distinct political identities, shaped by historical, economic, and cultural factors. Consider the American South, where a legacy of agrarian economies and the Civil War has fostered a political culture that values states' rights and conservative social policies. Similarly, the industrial Northeast, with its history of urbanization and labor movements, tends to lean towards progressive policies and federal intervention. These regional identities are not static; they evolve in response to demographic shifts, economic changes, and national political trends. For instance, the Sun Belt’s rapid growth in the late 20th century transformed it into a politically influential region, blending conservative and libertarian ideologies. Understanding these dynamics requires examining how local histories and economies intersect with broader national narratives.

To analyze how regional identities form, consider the role of geography itself. Mountainous regions, like the American West, often prioritize land use and environmental policies, while coastal areas focus on trade and maritime interests. Economic dependencies further entrench these identities—coal-dependent regions may resist environmental regulations, while tech hubs advocate for innovation-friendly policies. A practical tip for policymakers is to tailor messaging to align with these regional priorities. For example, framing climate policy as a job creator in renewable energy can resonate in regions with declining industrial bases. Caution, however, must be taken to avoid reinforcing stereotypes; regional identities are diverse within themselves, and overgeneralization can alienate specific communities.

Persuasively, regional identities can either unite or divide a nation, depending on how they are acknowledged and managed. In countries like India, regional parties often champion local languages and cultures, challenging the dominance of national parties. This can lead to healthier political competition but also risks fragmentation if regional loyalties overshadow national unity. A comparative look at Canada reveals how federal structures can accommodate regional identities through devolved powers, as seen in Quebec’s linguistic and cultural autonomy. For nations grappling with sectionalism, a takeaway is to balance regional representation with shared national goals, perhaps through constitutional reforms or inclusive policy frameworks.

Descriptively, the development of regional political cultures is a slow-burning process, often invisible until it manifests in voting patterns or social movements. Take the Rust Belt in the U.S., where deindustrialization fueled economic anxiety, contributing to a shift toward populist politics. Similarly, Scotland’s push for independence reflects a distinct political identity rooted in historical grievances and differing policy preferences. To foster understanding, engage with local narratives through media, literature, and community dialogues. A practical step is to create platforms where regional voices can shape national discourse, ensuring that their concerns are not overshadowed by dominant narratives.

Instructively, individuals can contribute to bridging regional divides by educating themselves on the histories and challenges of different areas. For instance, a Midwesterner learning about the economic struggles of Appalachia can foster empathy and reduce political polarization. Organizations can play a role by implementing regional diversity training, ensuring that employees understand the cultural and political contexts of their colleagues. A cautionary note: avoid tokenism by ensuring these efforts lead to tangible policy or behavioral changes. Ultimately, recognizing and respecting regional identities is not about fragmenting a nation but about building a more inclusive and responsive political system.

Navigating School Politics: Strategies for Success and Stress-Free Survival

You may want to see also

Economic Interests: Divergent economic priorities among regions driving political divisions and conflicts

Economic disparities between regions often serve as the bedrock for political sectionalism, where divergent economic priorities fracture unity and fuel conflict. Consider the United States in the 19th century, when the agrarian South clashed with the industrial North over tariffs, labor systems, and economic policies. The South’s reliance on slave labor and cotton exports pitted it against the North’s manufacturing interests, culminating in irreconcilable differences that led to the Civil War. This historical example underscores how economic structures, when misaligned, can become catalysts for political division.

To understand this dynamic, examine the role of resource distribution and industry specialization. Regions dependent on agriculture, mining, or manufacturing develop distinct economic priorities shaped by their environments and labor forces. For instance, coal-dependent states prioritize policies protecting fossil fuel industries, while tech hubs advocate for innovation and deregulation. These competing interests create friction in legislative bodies, where representatives champion regional agendas over national cohesion. Policymakers must navigate this complexity, balancing localized demands with broader economic strategies to avoid deepening divides.

A persuasive argument emerges when considering the impact of globalization and trade policies. Free trade agreements, such as NAFTA, disproportionately benefited certain regions while devastating others, as seen in the decline of Rust Belt manufacturing in the U.S. Such economic shocks foster resentment and political polarization, as affected communities feel abandoned by national leadership. To mitigate this, governments should implement targeted economic development programs, retraining initiatives, and transitional support for displaced workers. Failure to address these disparities risks further entrenching sectionalism and eroding trust in institutions.

Comparatively, the European Union faces similar challenges, where wealthier northern nations like Germany clash with southern economies like Greece over fiscal policies and debt relief. These tensions highlight how economic interdependence, without equitable distribution of benefits, can exacerbate regional divisions. A descriptive lens reveals the human cost: rising unemployment, stagnant wages, and social unrest in economically marginalized areas. Addressing these issues requires not just economic reforms but also a cultural shift toward solidarity and shared prosperity.

In conclusion, divergent economic priorities among regions are a potent driver of political sectionalism, rooted in historical, structural, and global factors. By analyzing resource distribution, industry specialization, and the impact of globalization, policymakers can devise strategies to bridge economic gaps. Practical steps include investing in infrastructure, diversifying regional economies, and fostering dialogue between competing interests. Without proactive measures, economic disparities will continue to fuel political conflicts, undermining social cohesion and national stability.

Political Fashion: How Clothing Shapes Power, Protest, and Identity

You may want to see also

Social Values: Differences in social norms, beliefs, and ideologies creating sectional political alignments

Social values, deeply ingrained in communities, often serve as the bedrock for political sectionalism. Consider the stark divide between urban and rural areas in many countries. Urban centers, with their diverse populations and exposure to global ideas, tend to embrace progressive social norms like LGBTQ+ rights, multiculturalism, and environmental sustainability. In contrast, rural regions, rooted in tradition and homogeneity, often prioritize conservative values such as religious doctrine, individualism, and local economic interests. These contrasting social values create distinct political alignments, with urban areas leaning left and rural areas tilting right, fragmenting the political landscape into predictable sections.

To understand how social values drive sectionalism, examine the role of education and media consumption. Communities with higher educational attainment and access to diverse media sources are more likely to adopt liberal ideologies, emphasizing equality and social justice. Conversely, areas with limited educational opportunities and reliance on localized media often reinforce conservative beliefs, focusing on stability and traditional hierarchies. This divergence in information exposure and interpretation solidifies sectional political identities, as individuals align with parties that mirror their social values. For instance, debates over issues like gun control or healthcare reform often break along these lines, with each section advocating for policies that reflect their unique worldview.

A persuasive argument can be made that addressing sectionalism requires bridging the gap between these social value systems. Policymakers and community leaders must engage in cross-sectional dialogue, fostering understanding rather than deepening divisions. Practical steps include organizing town hall meetings that bring together urban and rural residents, creating educational programs that highlight shared values, and promoting media literacy to combat echo chambers. By encouraging empathy and collaboration, societies can mitigate the polarizing effects of differing social norms, beliefs, and ideologies.

Comparatively, historical examples illustrate the enduring impact of social values on sectionalism. The American Civil War, rooted in economic and moral disagreements over slavery, exemplifies how divergent social ideologies can lead to political fracture. Similarly, contemporary debates over immigration in Europe reflect clashes between multiculturalism and nationalism, further entrenching sectional divides. These cases underscore the need for proactive measures to reconcile conflicting social values before they escalate into political crises. By learning from history, societies can navigate the complexities of sectionalism with greater foresight and unity.

Finally, a descriptive lens reveals how social values manifest in everyday life, shaping political alignments. In neighborhoods, churches, and workplaces, individuals gravitate toward like-minded groups, reinforcing their beliefs and creating microcosms of sectionalism. For example, a community that values religious freedom may oppose government policies perceived as infringing on those beliefs, while another prioritizing public safety might support stricter regulations. These localized expressions of social values collectively contribute to broader political sectionalism, highlighting the importance of addressing differences at the grassroots level. By acknowledging and respecting these variations, societies can foster a more inclusive and cohesive political environment.

Mastering Polite Responses: A Guide to Answering Questions Gracefully

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$10.7 $19.95

Historical Grievances: Past events or injustices fueling ongoing regional political tensions and rivalries

Historical grievances, often rooted in past injustices or conflicts, serve as fertile soil for ongoing regional political tensions and rivalries. These grievances, whether real or perceived, create a collective memory that shapes identities and fuels sectionalism. Consider the American South, where the legacy of the Civil War and Reconstruction continues to influence political attitudes. The defeat of the Confederacy and the imposition of Northern policies are still cited by some as reasons for resistance to federal authority, illustrating how historical wounds can persist for generations.

To understand the mechanics of this phenomenon, examine the role of narrative in perpetuating sectionalism. Communities often craft and retell stories of past wrongs to justify present-day divisions. For instance, in the Balkans, the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 remains a rallying cry for Serbian nationalism, despite centuries having passed. This narrative is not merely historical; it is actively used to mobilize political support and deepen regional rivalries. Such storytelling transforms history into a weapon, reinforcing us-versus-them mentalities.

A practical takeaway for addressing historical grievances lies in acknowledging their validity while fostering dialogue. Ignoring these wounds or dismissing them as irrelevant only deepens resentment. In Northern Ireland, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 succeeded in part because it recognized the historical grievances of both Unionists and Nationalists, creating a framework for reconciliation. This approach requires political leaders to balance accountability for the past with a commitment to a shared future, a delicate but necessary task.

Comparatively, regions that fail to address historical grievances often see sectionalism harden into intractable conflict. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict, for example, is deeply rooted in competing claims over land and historical injustices. Without a mechanism to address these grievances, political tensions remain high, and sectional identities become increasingly polarized. This comparison underscores the importance of proactive measures to prevent history from becoming a permanent barrier to cooperation.

Finally, consider the role of education in mitigating the impact of historical grievances. Teaching history in a way that encourages critical thinking and empathy can help break cycles of resentment. In Rwanda, post-genocide education programs focus on shared humanity rather than ethnic divisions, aiming to prevent future conflicts. While this approach is not a quick fix, it offers a long-term strategy for reducing sectionalism by reshaping how communities understand their past and envision their future.

Fiji-Taiwan Relations: Political Implications and Global Impact Analysis

You may want to see also

Policy Disputes: Regional disagreements over specific policies (e.g., tariffs, slavery) exacerbating sectionalism

Regional disagreements over specific policies have long been a catalyst for deepening political sectionalism, creating fault lines that divide nations along geographic, economic, and cultural boundaries. Consider the contentious issue of tariffs in 19th-century America, where Northern industrialists championed protective tariffs to shield their burgeoning factories from foreign competition, while Southern agrarian interests vehemently opposed such measures, viewing them as a tax on their imported goods and a subsidy for Northern industry. This policy dispute was not merely an economic quarrel but a reflection of fundamentally different regional economies and priorities, each side perceiving the other’s agenda as a threat to its survival. The resulting tension did not remain confined to legislative chambers; it permeated public discourse, media, and social attitudes, reinforcing a sense of "us versus them" that exacerbated sectional divides.

To understand how such disputes escalate sectionalism, examine the role of slavery in the antebellum United States. Here, policy disagreements were not just about economic systems but about moral and existential questions. The North’s push for restrictions on slavery, culminating in proposals like the Wilmot Proviso, clashed directly with the South’s insistence on its right to expand slavery into new territories. These disputes were not isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern where regional identities became inextricably linked to specific policies. The South’s perception of Northern aggression on slavery fueled a narrative of victimhood and justified secessionist sentiments, while the North viewed Southern resistance as obstructionist and morally bankrupt. This dynamic illustrates how policy disputes can transform from political disagreements into existential battles over regional identity and autonomy.

A comparative analysis of modern policy disputes reveals similar patterns. For instance, debates over climate policy in the U.S. often pit coastal states advocating for stringent environmental regulations against inland states reliant on fossil fuel industries. Coastal regions, more vulnerable to rising sea levels and extreme weather, prioritize green energy initiatives, while inland states fear economic collapse from restrictive policies. These disagreements are not merely about carbon emissions but about competing visions of economic survival and regional prosperity. As with tariffs and slavery, the absence of a unifying national narrative allows these disputes to harden into sectional identities, with each region viewing the other’s policies as a direct assault on its way of life.

To mitigate the sectionalism fueled by policy disputes, policymakers must adopt strategies that acknowledge regional diversity while fostering national cohesion. One practical approach is to design policies with built-in regional flexibility, allowing states or localities to adapt national frameworks to their specific needs. For example, a federal climate policy could include incentives for renewable energy adoption in rural areas, addressing economic concerns while advancing environmental goals. Additionally, fostering cross-regional dialogue and collaboration can help bridge divides by humanizing opposing viewpoints and identifying shared interests. Ultimately, the goal is not to eliminate regional differences but to prevent them from becoming irreconcilable barriers to national unity. By treating policy disputes as opportunities for innovation rather than division, societies can navigate sectional tensions without fracturing along regional lines.

Measuring Political Equality: Tools, Challenges, and Pathways to Fair Representation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political sectionalism refers to the division of a country or region into distinct sections, each with its own interests, values, and political priorities, often leading to conflict or competition between these sections.

Political sectionalism is typically caused by differences in geography, economy, culture, or ideology among regions, which can lead to competing interests and divergent political agendas.

Political sectionalism can hinder effective governance by creating polarization, gridlock, and difficulty in reaching national consensus, as regions prioritize their own interests over collective goals.