Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) politics, often referred to as Wobbly politics, are rooted in the organization's founding principles of revolutionary industrial unionism, solidarity, and direct action. Established in 1905, the IWW advocates for the unity of the working class across industries, races, and genders to challenge capitalist exploitation and build a worker-controlled economy. Its politics emphasize grassroots organizing, workplace democracy, and the abolition of the wage system, envisioning a society where labor is not commodified. Unlike traditional trade unions, the IWW focuses on class struggle rather than reformist bargaining, promoting strikes, boycotts, and collective resistance as tools for empowerment. Central to its ideology is the slogan An injury to one is an injury to all, reflecting its commitment to global worker solidarity and the ultimate goal of replacing capitalism with a cooperative commonwealth.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Anti-Capitalist | Advocates for the abolition of capitalism, viewing it as exploitative and inherently oppressive. |

| Worker Solidarity | Emphasizes unity among all workers across industries, races, genders, and nationalities. |

| Direct Action | Promotes direct methods like strikes, boycotts, and workplace occupations to achieve labor goals. |

| Industrial Unionism | Organizes workers by industry rather than by trade, aiming to build a broad-based labor movement. |

| One Big Union | Seeks to unite all workers into a single, powerful union capable of challenging capitalist systems. |

| Grassroots Democracy | Encourages democratic decision-making at the local level, with workers controlling their own organizations. |

| Internationalism | Supports global solidarity among workers, recognizing that labor struggles transcend national borders. |

| Anti-Authoritarian | Opposes hierarchical structures and authoritarianism, both in society and within the organization. |

| Class Struggle | Focuses on the conflict between the working class and the capitalist class as the central issue of politics. |

| Worker Empowerment | Aims to empower workers to take control of their workplaces and lives through collective action. |

| Socialism | Advocates for a socialist society where the means of production are owned and controlled by the workers. |

| Inclusive Membership | Welcomes all workers regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, or skill level, promoting diversity and equality. |

| Educational Focus | Emphasizes education and skill-building to equip workers with the knowledge to fight for their rights. |

| Historical Legacy | Builds on a legacy of radical labor activism, including the Wobblies' early 20th-century struggles. |

| Cultural Work | Uses art, music, and literature as tools for organizing and spreading the message of worker solidarity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Origins and Founding Principles

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), founded in 1905, emerged as a radical response to the limitations of mainstream labor unions. Unlike the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which focused on skilled workers and often excluded immigrants, women, and people of color, the IWW embraced an inclusive, revolutionary vision. Its founding convention in Chicago brought together socialists, anarchists, and disillusioned workers, united by a shared belief in the need for a global, class-based struggle against capitalism. This diverse coalition laid the groundwork for a union that would challenge not just wages and hours, but the very structure of the capitalist system.

At the heart of the IWW’s founding principles was the concept of "One Big Union," a unified organization transcending trade, race, and national boundaries. This idea was encapsulated in their Preamble, which declared, "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common." By rejecting craft unionism and advocating for solidarity among all workers, the IWW sought to build a movement capable of confronting capitalist exploitation on a global scale. Their slogan, "An injury to one is an injury to all," underscored this commitment to collective action and mutual aid.

The IWW’s tactics were as bold as their principles. They championed direct action—strikes, boycotts, and sabotage—over political lobbying or arbitration. This approach, known as "revolutionary industrial unionism," aimed to empower workers to take control of production and dismantle capitalist hierarchies from within. For example, the Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912, led by the IWW, demonstrated the power of solidarity and direct action, as workers of diverse backgrounds united to win significant concessions. Such actions exemplified the IWW’s belief that real change comes from the grassroots, not from legislative reform.

Despite its radical vision, the IWW faced immense challenges from its inception. Government repression, corporate opposition, and internal divisions often hindered its growth. Yet, its founding principles—solidarity, direct action, and a rejection of capitalism—continue to inspire labor movements worldwide. The IWW’s legacy reminds us that true liberation requires not just better working conditions, but a fundamental transformation of the systems that perpetuate inequality. For those seeking to build a more just world, the IWW’s origins offer both a blueprint and a cautionary tale.

Understanding Political Caricature: Art, Satire, and Social Commentary Explained

You may want to see also

Industrial Unionism vs. Craft Unionism

Industrial unionism and craft unionism represent two distinct approaches to labor organizing, each with its own philosophy, structure, and implications for workers. At its core, industrial unionism, championed by organizations like the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), advocates for uniting all workers within a specific industry, regardless of skill level or trade. In contrast, craft unionism organizes workers based on their specialized skills, such as carpenters or electricians, often excluding less-skilled laborers. This fundamental difference in scope shapes how these unions operate, negotiate, and address workplace inequalities.

Consider the practical implications of these models. Industrial unionism fosters solidarity across the entire workforce, from factory floor operatives to machine technicians, creating a unified front against employers. For instance, in a manufacturing plant, an industrial union would include assembly line workers, maintenance staff, and supervisors, all bargaining collectively. Craft unionism, however, might only represent skilled machinists, leaving other workers to fend for themselves. This fragmentation can weaken bargaining power and perpetuate hierarchies within the workforce, as seen historically in industries like construction, where skilled trades often prioritized their interests over those of laborers.

To illustrate further, imagine a strike in a textile mill. An industrial union would mobilize all employees, from weavers to janitors, amplifying the impact of the strike and forcing management to address grievances comprehensively. A craft union, representing only skilled weavers, might achieve wage increases for its members but fail to improve conditions for the broader workforce. This example highlights industrial unionism’s emphasis on collective action and its potential to dismantle class divisions within industries. Craft unionism, while effective for securing specialized benefits, often falls short in fostering broader workplace equity.

Adopting industrial unionism requires a strategic shift in organizing tactics. Organizers must focus on building trust across diverse worker groups, addressing shared concerns like wages, safety, and job security. For instance, the IWW’s “One Big Union” philosophy encourages workers to see themselves as part of a larger struggle, transcending skill-based divisions. Craft unions, on the other hand, thrive on exclusivity, often requiring apprenticeships or certifications for membership. While this ensures high standards within specific trades, it can alienate workers without formal qualifications, perpetuating inequality.

In conclusion, the choice between industrial and craft unionism hinges on the desired outcomes for workers. Industrial unionism offers a path toward inclusive, industry-wide solidarity, challenging systemic inequalities. Craft unionism, while effective for skilled workers, risks reinforcing workplace hierarchies. For those seeking to organize in the spirit of the IWW, embracing industrial unionism means prioritizing unity, equity, and collective power—a radical departure from the fragmented approach of craft unions.

Unfiltered AM Politics: Debates, Insights, and Breaking News Live

You may want to see also

Global Influence and Chapters

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), founded in 1905, has cultivated a global footprint through its unique brand of revolutionary unionism. Unlike traditional trade unions, the IWW organizes across industries and national borders, advocating for a worker-controlled economy. This transnational approach has led to the establishment of chapters in over 50 countries, from Australia to Zimbabwe. Each chapter adapts the IWW’s core principles—direct action, solidarity, and the abolition of the wage system—to local contexts, creating a diverse yet unified movement. For instance, the IWW’s Australian chapter has been instrumental in campaigns for fair wages in the hospitality sector, while its South African branch focuses on combating labor exploitation in mining communities.

To start or join an IWW chapter, follow these steps: first, identify local labor issues that align with the IWW’s principles. Second, connect with existing members or use the IWW’s global network to gather resources. Third, organize small-scale actions, such as workplace protests or community education events, to build momentum. Caution: avoid isolating your chapter by neglecting to engage with broader labor movements or local communities. Successful chapters, like those in the UK and Canada, thrive by fostering alliances with other unions and grassroots organizations.

A comparative analysis reveals that IWW chapters in countries with strong labor laws, such as Sweden and Germany, often focus on systemic change, while those in regions with weaker protections, like India and Mexico, prioritize immediate workplace struggles. This adaptability underscores the IWW’s strength but also highlights challenges in maintaining ideological consistency across diverse political landscapes. For example, the Swedish chapter advocates for cooperative ownership models, whereas the Mexican chapter emphasizes worker safety in maquiladoras.

Persuasively, the IWW’s global influence lies in its ability to inspire localized resistance while maintaining a universal vision. By decentralizing power and encouraging autonomous chapters, the IWW avoids the bureaucratic pitfalls of traditional unions. However, this model requires constant communication and solidarity among chapters to prevent fragmentation. Practical tip: utilize digital platforms like the IWW’s global forum to share strategies and resources, ensuring that chapters remain interconnected despite geographical distances.

Descriptively, an IWW chapter meeting might involve workers from various industries discussing ongoing campaigns, planning direct actions, and sharing stories of resistance. In Melbourne, for instance, a chapter meeting could include hospitality workers strategizing a rent strike, while in Johannesburg, miners might coordinate a safety audit protest. These gatherings embody the IWW’s ethos of worker-led organizing, where every voice contributes to the collective struggle.

In conclusion, the IWW’s global influence and chapters demonstrate the power of decentralized, transnational solidarity. By combining local adaptability with a universal vision, the IWW continues to challenge capitalist exploitation worldwide. Whether you’re in a bustling city or a remote village, the IWW offers a framework for workers to unite, organize, and fight for a better future.

Are Anonymous Political Contributions Protected by Free Speech Rights?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Key Campaigns and Strikes

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), known as the Wobblies, have a storied history of organizing key campaigns and strikes that challenge capitalist exploitation and advocate for workers' rights. One of their most influential campaigns was the Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912, also known as the "Bread and Roses" strike. Over 20,000 immigrant workers, primarily women and children, walked off the job in Lawrence, Massachusetts, to protest wage cuts and inhumane working conditions. The IWW's strategy of solidarity across ethnic lines and their emphasis on direct action led to a successful outcome, with workers winning wage increases and improved conditions. This strike became a blueprint for future labor movements, demonstrating the power of diverse, unified resistance.

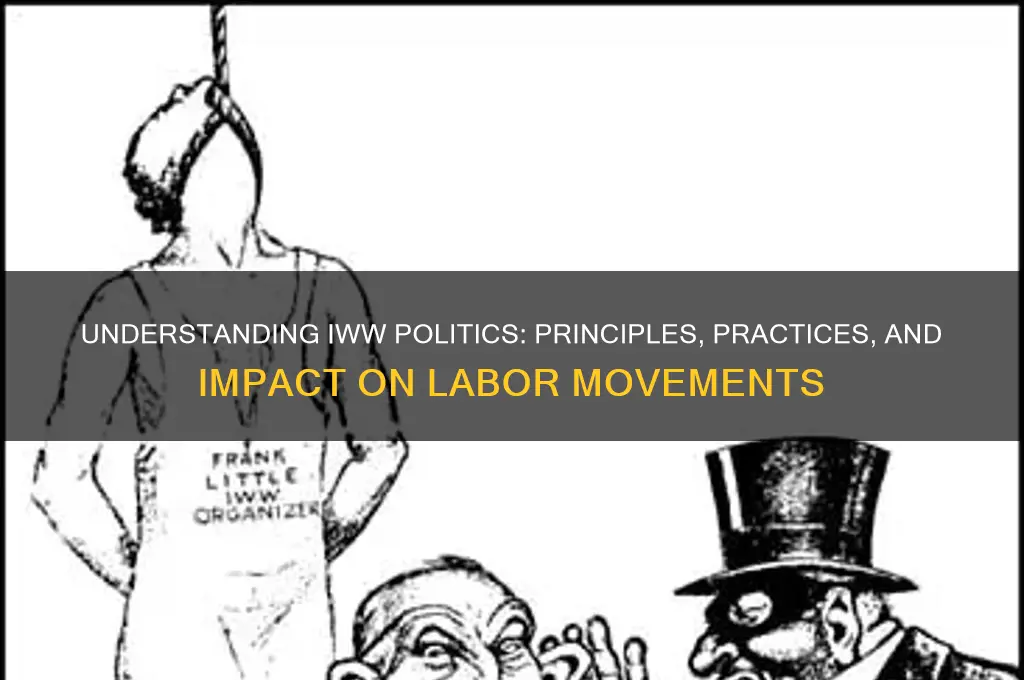

Another pivotal campaign was the Everett Massacre of 1916, which highlights the IWW's commitment to free speech and labor rights. Wobblies organized a rally in Everett, Washington, to support striking shingle weavers, but local authorities and vigilantes violently suppressed the gathering, resulting in several deaths. Despite the tragedy, the IWW's persistence in defending workers' rights and their willingness to confront systemic violence underscored their dedication to the cause. This event also drew national attention to the harsh realities faced by laborers and the lengths to which power structures would go to silence dissent.

In the agricultural sector, the IWW's Wheatland Hop Riot of 1913 stands out as a critical moment in the fight for migrant workers' rights. After a peaceful protest over unpaid wages turned violent due to police intervention, the IWW organized a broader campaign to expose the exploitation of seasonal laborers. This strike not only highlighted the dire conditions in the fields but also laid the groundwork for future agricultural labor movements, such as those led by Cesar Chavez decades later. The IWW's ability to mobilize and amplify the voices of marginalized workers remains a hallmark of their approach.

A comparative analysis of these campaigns reveals a consistent IWW strategy: solidarity, direct action, and a focus on the most vulnerable workers. Unlike traditional unions, the IWW has always prioritized organizing across industries and ethnicities, challenging the divide-and-conquer tactics of employers. Their strikes are not just about immediate gains but also about building a broader movement for economic justice. For instance, the Lawrence strike's success was as much about winning higher wages as it was about proving the efficacy of multicultural unity in labor struggles.

To replicate the IWW's impact in modern campaigns, organizers should take note of three key takeaways: build coalitions across diverse groups, prioritize direct action over bureaucratic negotiation, and frame struggles in terms of human dignity rather than mere economics. For example, in today's gig economy, workers can draw inspiration from the IWW's model by forming cross-platform alliances and using strikes or boycotts to demand fair pay and benefits. By studying these historical campaigns, contemporary activists can adapt the Wobblies' principles to address 21st-century labor challenges, ensuring their legacy continues to inspire future generations.

Am I a Political Centrist? Exploring Middle-Ground Ideologies and Beliefs

You may want to see also

Modern Relevance and Challenges

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), founded in 1905, advocated for direct action, solidarity, and worker control across industries. Today, their emphasis on grassroots organizing and anti-capitalist struggle resonates in movements like the Fight for $15 and gig worker unions. However, modern challenges include adapting to the gig economy’s fragmented workforce and countering anti-union legislation in right-to-work states. For instance, app-based workers face algorithmic management, making traditional strikes less effective. To remain relevant, IWW-inspired tactics must integrate digital tools for mobilization while maintaining their core principles of direct democracy and cross-industry solidarity.

Consider the gig economy’s unique hurdles: workers are classified as independent contractors, stripping them of labor protections. Here’s a practical strategy: use social media platforms to coordinate "virtual picket lines" that disrupt algorithms by mass-reporting exploitative practices. Pair this with local meetups to build trust and shared identity, a key IWW tenet. Caution: avoid over-reliance on digital solutions, as they can alienate workers with limited tech access. The takeaway? Blend old-school solidarity with modern tools to address 21st-century exploitation.

Persuasively, the IWW’s "One Big Union" vision offers a counter to the atomization of modern labor. Unlike traditional unions focused on single industries, IWW’s inclusive model can unite warehouse workers, delivery drivers, and retail employees under a common cause. This approach is particularly potent in low-wage sectors where workers are often marginalized by race, gender, or immigration status. For example, the IWW-affiliated Starbucks Workers United campaign leverages this inclusivity to challenge corporate giants. However, scaling such efforts requires overcoming internal divisions and external suppression, demanding patience and strategic flexibility.

Comparatively, while traditional unions negotiate within capitalist frameworks, IWW politics seek to dismantle them. This radical stance is both its strength and weakness. In countries with strong labor laws, like Sweden, IWW-style direct action complements legal protections. In the U.S., however, such tactics often face harsh backlash. A practical tip: focus on small, winnable battles (e.g., securing hazard pay) to build momentum for larger systemic change. The challenge lies in balancing immediate gains with long-term revolutionary goals, ensuring workers remain engaged without sacrificing ideological purity.

Descriptively, imagine a warehouse worker in the Midwest, paid $12/hour with no benefits, joining an IWW-inspired collective. Through workshops on labor history and role-playing strike scenarios, they learn to challenge management’s divide-and-conquer tactics. This worker’s story illustrates the IWW’s enduring relevance: empowering individuals to see themselves as part of a global class struggle. Yet, such efforts require sustained effort and resources, often scarce in underfunded grassroots movements. The challenge is to scale these micro-level successes into macro-level change, ensuring the IWW’s legacy thrives in an era of unprecedented inequality.

Understanding the Political Model: Frameworks Shaping Governance and Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

IWW stands for the Industrial Workers of the World, a global labor union and political organization founded in 1905. It advocates for workers' rights, socialism, and industrial unionism.

The IWW is guided by principles of solidarity, direct action, and the abolition of the wage system. It promotes worker-controlled industries and opposes capitalism and authoritarianism.

Unlike traditional unions, the IWW organizes across industries, includes all workers regardless of skill or trade, and focuses on revolutionary change rather than negotiating within the capitalist system.