Impeachment is a formal political process in which a public official, typically a high-ranking government officer such as a president, judge, or legislator, is charged with serious misconduct or crimes committed while in office. Rooted in English common law and enshrined in many democratic constitutions, including the United States, impeachment serves as a mechanism to hold leaders accountable and protect the integrity of governance. It is not a direct removal from office but rather a formal accusation, often initiated by a legislative body, that triggers a trial to determine whether the official should be removed. While the specific procedures and grounds for impeachment vary by country, it is universally regarded as a grave and rare measure, reserved for offenses such as treason, bribery, or abuse of power. The process underscores the principle of checks and balances, ensuring that no individual, regardless of their position, is above the law.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Impeachment is a formal process in which a public official, such as a president, judge, or other high-ranking official, is charged with serious misconduct or crimes while in office. |

| Purpose | To hold officials accountable for actions that violate their oath of office or commit "high crimes and misdemeanors." |

| Process | Typically involves two stages: 1) Impeachment (formal charges by a legislative body) and 2) Trial (judgment by another body, often the upper house of the legislature). |

| Outcome | If convicted, the official may be removed from office, disqualified from future office, or face other penalties. |

| Legal Basis | Derived from constitutional or statutory provisions, e.g., Article II, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution. |

| Examples of Misconduct | Treason, bribery, obstruction of justice, abuse of power, or other serious offenses. |

| Historical Examples | U.S. Presidents Andrew Johnson (1868), Bill Clinton (1998), and Donald Trump (2019, 2021); Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff (2016). |

| Distinction from Recall | Impeachment is a legal process for removal, while recall is a voter-driven process to remove an elected official. |

| Global Variations | Procedures and criteria vary by country, e.g., parliamentary systems may have different mechanisms than presidential systems. |

| Political Implications | Often highly partisan and can significantly impact public trust in government and the official's legacy. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition: Impeachment is a formal process to charge a public official with misconduct

- Historical Context: Origins in British law, adopted in U.S. Constitution (Article II, Section 4)

- Process: Begins in House (majority vote), trial in Senate (2/3 vote to convict)

- Grounds: Treason, bribery, high crimes, misdemeanors, or abuse of power

- Outcomes: Removal from office, disqualification from future positions, no criminal penalties

Definition: Impeachment is a formal process to charge a public official with misconduct

Impeachment, at its core, is a constitutional mechanism designed to hold public officials accountable for egregious misconduct. Unlike a criminal trial, it is a political process initiated by a legislative body, typically the lower house, to bring formal charges against an official. These charges, known as articles of impeachment, must outline specific allegations of wrongdoing, such as treason, bribery, or high crimes and misdemeanors. The process is not a conviction but rather an indictment, setting the stage for a trial in the upper house, where a two-thirds majority is required to remove the official from office. This distinction is crucial: impeachment is the accusation, not the punishment.

Consider the steps involved in this formal process. First, the legislative body investigates the allegations, often through a committee tasked with gathering evidence and testimony. If sufficient grounds are found, articles of impeachment are drafted and voted on. A simple majority is usually required to pass these articles. Next, the case moves to the upper house, where a trial is conducted, often with members of the lower house acting as prosecutors. The official in question may present a defense, and the trial concludes with a vote. Removal from office is the most severe consequence, but additional penalties, such as disqualification from holding future office, may also be imposed. This structured approach ensures that the process is deliberate and fair, balancing the need for accountability with the protection of due process.

A comparative analysis reveals that impeachment is not unique to any single country but is a feature of many democratic systems. In the United States, for example, the Constitution explicitly outlines the process, while in the United Kingdom, it is rooted in parliamentary tradition. Despite these differences, the underlying principle remains the same: to safeguard the integrity of public office by providing a legal means to address serious misconduct. However, the rarity of successful impeachments underscores its gravity; it is a tool reserved for the most extreme cases, not a routine political maneuver.

Practical considerations highlight the challenges of impeachment. The process is inherently political, often influenced by partisan dynamics, which can complicate its impartiality. For instance, public opinion and media coverage can sway legislators, potentially undermining the process's objectivity. Additionally, the high threshold for conviction—a two-thirds majority in many systems—means that even well-founded charges may fail to result in removal. Officials and citizens alike must understand these complexities to appreciate both the power and limitations of impeachment as a mechanism for accountability.

In conclusion, impeachment serves as a critical check on the power of public officials, ensuring they remain answerable to the law and the people they serve. Its formal structure, from investigation to trial, reflects a commitment to fairness and due process. While it is a potent tool, its effectiveness depends on the integrity of those who wield it and the public's trust in the process. By understanding its definition, steps, and implications, we can better navigate its role in maintaining the health of democratic institutions.

History's Echoes: Shaping Politics, Power, and Modern Society's Future

You may want to see also

Historical Context: Origins in British law, adopted in U.S. Constitution (Article II, Section 4)

The concept of impeachment, a mechanism to hold public officials accountable, traces its roots to medieval England, where it emerged as a tool to address abuses of power by royal appointees. By the 14th century, the British Parliament formalized impeachment as a process to try officials for "high crimes and misdemeanors," a phrase that would later resonate in American constitutional law. This early framework was not a criminal proceeding but a political one, designed to protect the realm from corruption and tyranny. Parliament’s role in impeachment reflected its growing authority to check the monarchy, setting a precedent for balancing power between branches of government.

When the framers of the U.S. Constitution sought to establish a system of checks and balances, they drew directly from this British tradition. Article II, Section 4, of the Constitution explicitly empowers Congress to remove the President, Vice President, and all civil officers for "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors." This language mirrors the British standard, though its application in the American context was tailored to a republic rather than a monarchy. The Founding Fathers viewed impeachment as a safeguard against executive overreach, ensuring that no official, regardless of rank, could act above the law.

The adoption of impeachment in the U.S. Constitution was not without debate. Some framers feared it could become a weapon for partisan attacks, while others argued it was essential to preserve the integrity of the new government. The compromise reached—a two-step process requiring a House majority to impeach and a two-thirds Senate vote to convict—was designed to make impeachment deliberate and difficult, reflecting its gravity. This structure underscores the framers’ intent: impeachment is a political remedy, not a legal one, aimed at protecting the public trust rather than punishing individual wrongdoing.

Practical examples from British history informed the framers’ thinking. For instance, the 1788 impeachment of Warren Hastings, Governor-General of India, demonstrated how the process could address corruption and abuse of power in colonial administration. Similarly, the 1649 trial of King Charles I, though ending in execution, highlighted the dangers of politicizing impeachment. These cases shaped the American understanding of impeachment as a measured, constitutional response to misconduct, distinct from criminal prosecution or revolution.

In applying this historical context today, it’s crucial to recognize impeachment’s dual nature: it is both a legal procedure and a political act. While rooted in British law, its American incarnation reflects the unique challenges of a democratic republic. For practitioners of constitutional law or students of political history, understanding this lineage provides clarity on impeachment’s purpose—not to settle policy disputes or punish unpopular decisions, but to address grave breaches of public trust. This distinction remains vital in interpreting Article II, Section 4, and its role in modern governance.

Is AOC Leaving Politics? Analyzing Her Future and Impact

You may want to see also

Process: Begins in House (majority vote), trial in Senate (2/3 vote to convict)

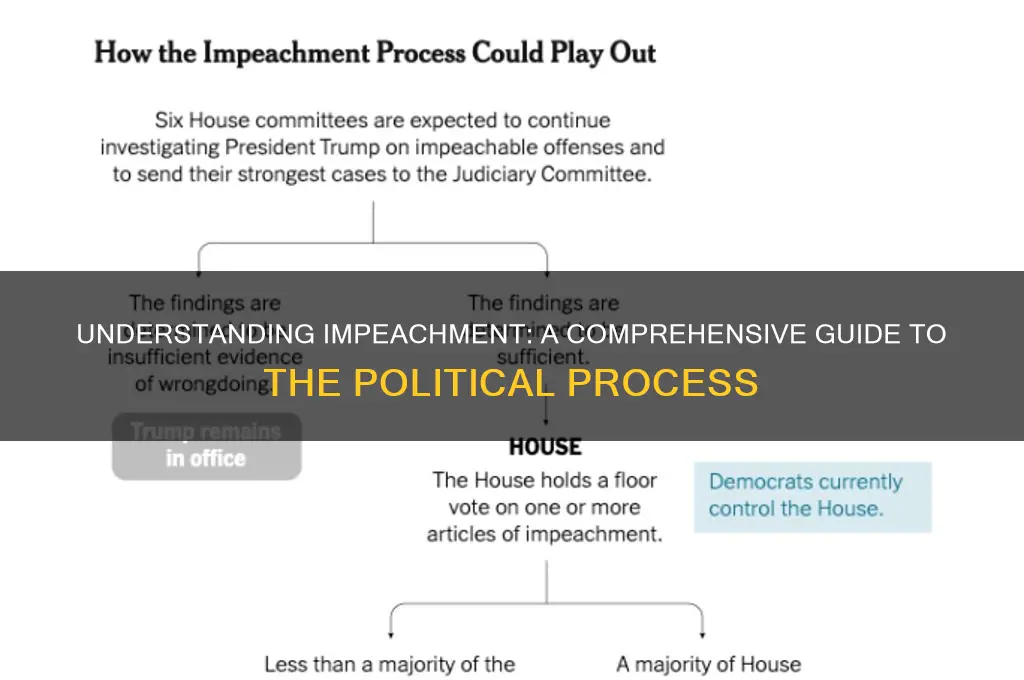

Impeachment, a constitutional mechanism to address serious misconduct by federal officials, is a two-stage process rooted in checks and balances. It begins in the House of Representatives, where the focus is on investigation and accusation, not conviction. Here’s how it works: the House Judiciary Committee conducts hearings, gathers evidence, and drafts articles of impeachment—formal charges akin to an indictment. If approved by the committee, these articles go to the full House for a vote. A simple majority (218 votes in the current 435-member House) is required to impeach. This step is procedural, not punitive; it merely establishes that there is enough evidence to warrant a trial.

Once impeached, the process shifts to the Senate, where the trial unfolds. The Senate acts as both judge and jury, with the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court presiding if the President is on trial. House managers serve as prosecutors, presenting the case, while the impeached official’s defense team counters. Senators deliberate, question witnesses, and weigh the evidence. Conviction requires a two-thirds majority (67 votes in the 100-member Senate), a high bar designed to ensure bipartisan consensus for such a grave action. Notably, conviction removes the official from office and may bar them from future federal positions, though it does not impose criminal penalties.

A critical distinction exists between impeachment and removal. Impeachment by the House is a political act, often influenced by party dynamics and public opinion. The Senate trial, however, demands a higher standard of evidence and bipartisanship. For example, in 1998, President Bill Clinton was impeached by the House for perjury and obstruction of justice but acquitted in the Senate, where the 67-vote threshold was not met. This illustrates the process’s dual nature: accusatory in the House, deliberative in the Senate.

Practical considerations abound. The process is time-consuming, often taking months, and can paralyze governance. It also carries political risks; parties must balance constitutional duty with electoral consequences. For instance, during President Trump’s first impeachment in 2019, the House voted largely along party lines, while the Senate’s acquittal reflected partisan divisions. Citizens should note that impeachment is not a criminal trial but a constitutional remedy, requiring both legal and ethical scrutiny.

In summary, the impeachment process is a deliberate, structured mechanism to hold officials accountable. It begins with a House majority vote, emphasizing investigation, and culminates in a Senate trial requiring a two-thirds conviction. This design ensures that removal from office is neither arbitrary nor partisan, but a measured response to grave misconduct. Understanding this process empowers citizens to engage critically with its use and implications.

Frankenstein's Political Anatomy: Power, Creation, and Social Responsibility Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Grounds: Treason, bribery, high crimes, misdemeanors, or abuse of power

Impeachment, a constitutional mechanism to hold public officials accountable, hinges on specific grounds outlined in Article II, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution: treason, bribery, high crimes, misdemeanors, or abuse of power. These categories are deliberately broad, allowing for flexibility in addressing misconduct while ensuring that only the most serious offenses warrant removal from office. Each ground serves as a distinct yet interconnected pillar, reflecting the framers’ intent to safeguard democracy against corruption and tyranny.

Treason and bribery stand as the most explicit grounds for impeachment, rooted in historical precedents and legal clarity. Treason, defined as levying war against the United States or adhering to its enemies, is a rare charge but carries profound implications. Bribery, involving the exchange of favors for official actions, is more common and often tied to financial or political corruption. For instance, the 1974 articles of impeachment against President Nixon included allegations of accepting bribes, though he resigned before the process concluded. These grounds are straightforward, leaving little room for ambiguity, and serve as a clear deterrent against overt abuses of power.

High crimes and misdemeanors, however, are more nuanced and open to interpretation. Unlike criminal statutes, these terms encompass a broader range of misconduct, from illegal acts to violations of public trust. The 1998 impeachment of President Clinton, for example, centered on perjury and obstruction of justice, which were deemed high crimes despite not being treason or bribery. This flexibility allows impeachment to address evolving forms of misconduct, but it also invites partisan disputes. Critics argue that vague definitions risk politicizing the process, while proponents emphasize the need for adaptability in holding officials accountable.

Abuse of power, though not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, has emerged as a critical ground in modern impeachment proceedings. It refers to actions that exploit the office for personal or political gain, even if they do not violate specific laws. The 2019 impeachment of President Trump, for instance, alleged that he pressured Ukraine to investigate a political rival, leveraging foreign policy for personal benefit. This ground underscores the principle that public office is a public trust, not a tool for self-interest. While subjective, it ensures that officials cannot evade accountability by skirting legal technicalities.

In practice, these grounds often overlap, with impeachment articles combining multiple allegations to build a comprehensive case. For example, an official might face charges of bribery and abuse of power for the same act. This interplay highlights the complexity of political accountability and the need for a thorough, evidence-based process. Ultimately, the grounds for impeachment serve as a constitutional safeguard, reminding officials that no one is above the law and that the public’s trust is not to be betrayed.

Is Nozick a Political Liberal? Examining His Libertarian Philosophy

You may want to see also

Outcomes: Removal from office, disqualification from future positions, no criminal penalties

Impeachment, a political process rooted in holding public officials accountable, culminates in specific outcomes designed to address misconduct while maintaining the integrity of governance. The most immediate and visible consequence is removal from office, a measure reserved for violations deemed severe enough to warrant termination of the official’s tenure. This step is not automatic; it requires a trial and conviction, typically by a legislative body. For instance, in the United States, the House of Representatives impeaches, but the Senate conducts the trial and decides whether to remove the official. Removal is a powerful tool, signaling that the individual has betrayed public trust and can no longer serve effectively.

Beyond removal, disqualification from holding future office is another critical outcome of impeachment. This penalty extends the consequences beyond the immediate term, ensuring that individuals who abuse power are barred from returning to positions of authority. In some jurisdictions, disqualification requires a separate vote after conviction, adding an extra layer of scrutiny. This measure is particularly significant in democracies, where the recurrence of misconduct by the same individual could erode public confidence in institutions. For example, the U.S. Constitution allows for disqualification as a punishment following impeachment, though it has rarely been applied.

Importantly, impeachment does not impose criminal penalties, a distinction often misunderstood by the public. While the process may stem from criminal behavior, it is fundamentally a political mechanism, not a legal one. Conviction in an impeachment trial does not result in fines, imprisonment, or other criminal sanctions. Instead, it focuses on preserving the integrity of the office and the system. Criminal charges, if applicable, must be pursued separately through the judicial system. This separation ensures that impeachment remains a tool for addressing political misconduct rather than becoming a substitute for criminal justice.

Understanding these outcomes highlights the dual nature of impeachment: it is both punitive and protective. Removal and disqualification safeguard the public interest by eliminating officials who have violated their duties, while the absence of criminal penalties underscores its role as a political rather than judicial process. This balance ensures that impeachment serves as a check on power without overstepping into the realm of law enforcement. For those navigating the complexities of governance, recognizing these distinctions is essential to appreciating the full scope and purpose of impeachment.

Is Northwestern University Politically Biased? Exploring Its Orientation and Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Impeachment is a formal process in which a public official, typically a high-ranking government official like a president or judge, is charged with serious misconduct or crimes while in office. It is a constitutional mechanism to hold officials accountable.

Common grounds for impeachment include treason, bribery, and other high crimes and misdemeanors, which often involve abuse of power, corruption, or violation of public trust.

No, impeachment is only the formal charging process. Removal from office typically requires a separate trial and conviction, often conducted by a legislative body like the Senate in the U.S.