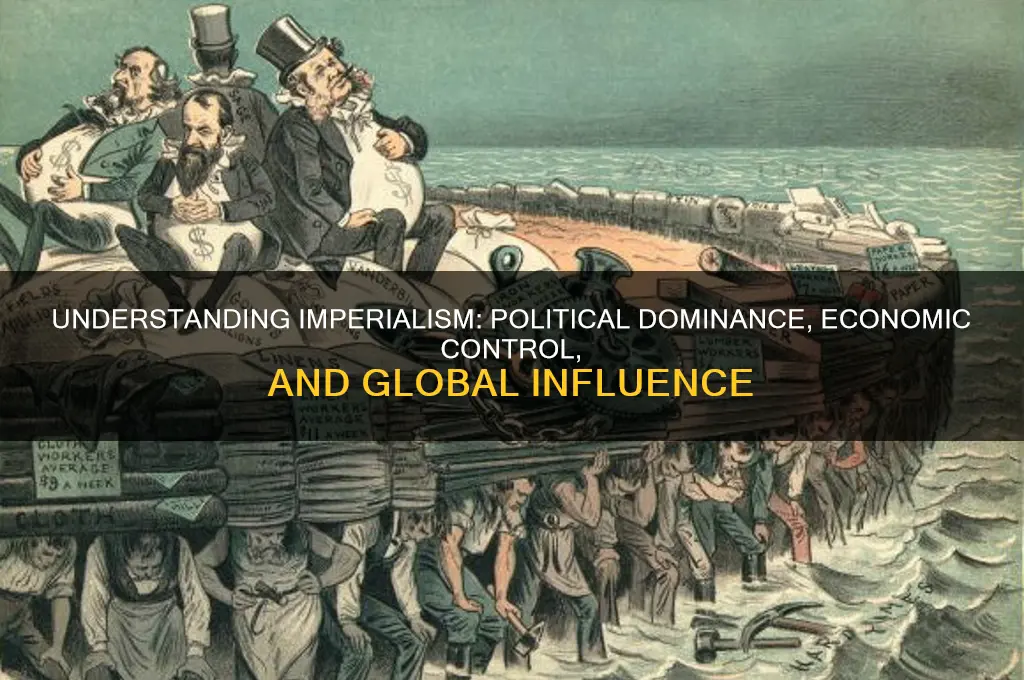

Imperialism in politics refers to the practice of a powerful nation extending its authority, control, or influence over other territories, often through military force, economic dominance, or cultural imposition. Rooted in the pursuit of economic resources, strategic advantages, and ideological supremacy, imperialism has historically involved the subjugation of less powerful regions, frequently resulting in exploitation, cultural erasure, and political dependency. While often justified by claims of civilizing missions or spreading superior values, it is fundamentally driven by the expansionist ambitions of dominant states. Its legacy continues to shape global power dynamics, influencing contemporary discussions on colonialism, sovereignty, and international relations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Domination | Imperialism involves the extension of a country's power through territorial acquisition or political and economic control over other nations. |

| Exploitation | It often leads to the exploitation of resources, labor, and markets of the dominated territories for the benefit of the imperial power. |

| Cultural Imposition | Imperial powers frequently impose their culture, language, religion, and social norms on the colonized populations, often suppressing local traditions. |

| Military Force | The use of military force or the threat thereof is a common tool to establish and maintain imperial control. |

| Economic Control | Imperialism often involves the establishment of economic systems that favor the imperial power, including trade policies, resource extraction, and infrastructure development. |

| Political Subjugation | Colonized regions are often governed by the imperial power, with limited or no political autonomy for the local population. |

| Colonial Administration | Imperial powers set up administrative systems to manage their colonies, often with local elites co-opted into the governance structure. |

| Racial and Social Hierarchy | Imperialism frequently creates and enforces racial and social hierarchies, with the colonizers considered superior to the colonized. |

| Resistance and Nationalism | Imperialism often sparks resistance movements and the rise of nationalism in colonized territories, leading to struggles for independence. |

| Global Influence | Imperial powers aim to project their influence globally, establishing spheres of influence and competing with other imperial powers for dominance. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic Exploitation: Extracting resources, labor, and wealth from colonized territories to enrich the imperial power

- Political Domination: Imposing control through military force, puppet governments, or direct colonial administration

- Cultural Hegemony: Spreading the dominant culture, language, and values of the imperial power

- Territorial Expansion: Acquiring new lands for strategic, economic, or ideological purposes

- Resistance Movements: Indigenous and local efforts to oppose and overthrow imperial rule

Economic Exploitation: Extracting resources, labor, and wealth from colonized territories to enrich the imperial power

Imperialism, at its core, is a system of domination where a powerful nation extends its authority over other territories, often through political, military, or economic means. One of its most insidious facets is economic exploitation, a process that systematically extracts resources, labor, and wealth from colonized territories to enrich the imperial power. This mechanism is not merely a byproduct of imperialism but a central strategy, meticulously designed to sustain and expand the dominance of the colonizer.

Consider the historical example of Belgian King Leopold II’s exploitation of the Congo Free State in the late 19th century. Under the guise of humanitarianism, Leopold established a private colony where rubber, ivory, and minerals were extracted at an unprecedented scale. Congolese laborers were subjected to brutal forced labor, with quotas enforced through violence. Those who failed to meet demands faced mutilation or death. The wealth generated from this exploitation—estimated at over $1.1 billion in today’s dollars—enriched Leopold personally and funded grandiose projects in Belgium, while the Congo was left impoverished and devastated. This case illustrates how economic exploitation under imperialism is not just about resource extraction but about creating a system of dependency and deprivation.

Analyzing the mechanics of economic exploitation reveals a deliberate structure. Imperial powers often impose unequal trade agreements, monopolize industries, and dismantle local economies to ensure a steady flow of wealth outward. For instance, during British colonial rule in India, the textile industry was systematically destroyed to make way for British-manufactured goods. Raw materials like cotton were exported to Britain, processed into textiles, and then sold back to India at inflated prices. This not only drained India’s wealth but also destroyed its self-sufficiency, forcing it into a subordinate economic position. Such practices highlight the strategic intent behind economic exploitation: to create a one-sided flow of resources that perpetuates the colonizer’s prosperity at the expense of the colonized.

To understand the enduring impact of economic exploitation, examine its modern manifestations. Multinational corporations, often backed by imperial powers, continue to extract resources from former colonies with little regard for local communities. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, cobalt mining—essential for smartphones and electric vehicles—generates billions for foreign companies while miners work in hazardous conditions for meager wages. Similarly, oil extraction in Nigeria has led to environmental degradation and social unrest, with profits largely benefiting foreign entities. These contemporary examples underscore how the legacy of imperial economic exploitation persists, adapting to new forms but retaining its exploitative core.

Addressing economic exploitation requires a multifaceted approach. First, transparency in global supply chains is essential to hold corporations accountable for their sourcing practices. Second, international policies must prioritize equitable trade agreements that benefit both parties, not just the economically dominant nation. Finally, former colonies must be empowered to reclaim control over their resources through capacity-building and legal frameworks. By dismantling the structures of exploitation, we can move toward a more just global economic system, one that does not replicate the injustices of imperialism.

Data's Role in Politics: Power, Influence, and Ethical Dilemmas Today

You may want to see also

Political Domination: Imposing control through military force, puppet governments, or direct colonial administration

Imperialism, at its core, is the extension of a nation's power through territorial acquisition or political and economic control over other regions. Political domination stands as one of its most overt manifestations, achieved through military force, the installation of puppet governments, or direct colonial administration. These methods are not relics of a bygone era; they persist in modern forms, often cloaked in the language of intervention or stabilization. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for recognizing how power is wielded on the global stage.

Consider the historical example of the British Raj in India. Direct colonial administration was employed to govern a vast and diverse population, imposing foreign rule through a combination of military might and bureaucratic control. The British established a system where local elites were co-opted into the administration, ensuring compliance while maintaining ultimate authority. This model of domination was replicated across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, leaving a legacy of economic exploitation and cultural erasure. The takeaway here is clear: direct administration is a blunt instrument of control, but its effectiveness lies in its ability to centralize power and suppress dissent.

Military force, another pillar of political domination, is often the precursor to more subtle forms of control. The 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq exemplifies this. Under the guise of eliminating weapons of mass destruction and promoting democracy, the invasion resulted in the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime and the installation of a government heavily influenced by foreign powers. While direct colonial administration was not imposed, the use of military force created a power vacuum filled by external actors, effectively rendering Iraq a puppet state. This approach highlights how military intervention can serve as both a tool of domination and a catalyst for long-term political control.

Puppet governments represent a more insidious form of political domination, where a nominally independent state is controlled from the shadows by a foreign power. During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union frequently employed this tactic, propping up regimes that aligned with their ideological and strategic interests. For instance, the U.S.-backed government in South Vietnam was dependent on American military and economic support, effectively functioning as a proxy in the broader struggle against communism. Such governments lack legitimacy and often face internal resistance, but they serve their sponsors by maintaining regional influence without the costs of direct administration.

To counter political domination, transparency and accountability are essential. International bodies like the United Nations must enforce norms against unilateral military interventions and support genuine self-determination. Civil society plays a critical role in exposing puppet regimes and holding external powers accountable. For individuals, staying informed and advocating for ethical foreign policies can help dismantle the structures of domination. The goal is not just to resist control but to foster a global order based on equality and mutual respect. Political domination may be a persistent feature of imperialism, but its tools and tactics can be challenged and, ultimately, overcome.

Is Christine Running for Office? Unraveling Her Political Ambitions

You may want to see also

Cultural Hegemony: Spreading the dominant culture, language, and values of the imperial power

Imperialism, as a political and economic system, often relies on more than just military conquest and territorial expansion. A crucial aspect of its enduring legacy is cultural hegemony—the process by which the dominant culture, language, and values of the imperial power are spread and internalized by the subjugated population. This phenomenon ensures that even after formal colonial rule ends, the influence of the imperial power persists, shaping societal norms, identities, and power structures.

Consider the British Empire’s imposition of English as the administrative and educational language in its colonies. In India, for instance, English replaced regional languages in schools and government, creating an elite class fluent in the colonizer’s tongue. This linguistic shift was not merely practical; it was a tool of control, fostering dependency on British systems and marginalizing indigenous knowledge. Today, English remains the lingua franca in many postcolonial nations, a testament to the enduring power of cultural hegemony. To counteract this, educators in countries like Nigeria and Kenya are now integrating local languages into curricula, aiming to reclaim cultural autonomy.

Cultural hegemony also operates through media and popular culture. Hollywood films, American music, and Western fashion trends dominate global markets, often overshadowing local artistic expressions. For example, Bollywood, while a powerhouse in its own right, frequently incorporates Western narratives and aesthetics, reflecting the pervasive influence of U.S. cultural exports. This global dissemination of Western ideals shapes aspirations and self-perceptions, often at the expense of diverse cultural identities. A practical step for individuals is to actively seek out and support local artists, filmmakers, and writers, thereby fostering cultural diversity and resistance to homogenization.

The spread of dominant values is another facet of cultural hegemony. Capitalism, individualism, and consumerism—core tenets of Western societies—are often presented as universal ideals. In Latin America, for instance, U.S. corporations have long promoted a culture of consumption, linking personal worth to material possessions. This has led to the erosion of communal values and traditional practices. To mitigate this, communities can organize cultural preservation programs, such as workshops on indigenous crafts or storytelling, reinforcing local values and histories.

Ultimately, cultural hegemony is a subtle yet powerful mechanism of imperialism, embedding the colonizer’s worldview into the fabric of colonized societies. Recognizing its manifestations—whether in language, media, or values—is the first step toward resistance. By prioritizing local languages, supporting indigenous arts, and reclaiming traditional values, societies can challenge the dominance of imperial cultures and forge paths toward genuine self-determination.

Understanding the Role and Influence of a Politico in Modern Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Territorial Expansion: Acquiring new lands for strategic, economic, or ideological purposes

Territorial expansion, a cornerstone of imperialism, involves the acquisition of new lands driven by strategic, economic, or ideological motives. Historically, nations have sought to extend their borders to secure resources, establish military strongholds, or spread cultural and political influence. For instance, the 19th-century Scramble for Africa saw European powers carving up the continent to exploit its raw materials and labor, illustrating how economic gain often fuels such expansion. This practice is not confined to the past; modern forms of territorial ambition, such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative, demonstrate how nations continue to seek influence through infrastructure and economic ties in strategically vital regions.

Strategic territorial expansion often revolves around securing geographic advantages, such as access to trade routes, natural defenses, or buffer zones against rivals. The United States’ acquisition of Alaska in 1867, initially seen as a frozen wasteland, later proved invaluable for its natural resources and strategic position during the Cold War. Similarly, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 was driven by its desire to maintain control over the Black Sea and its naval base in Sevastopol. These examples highlight how territorial expansion is frequently a calculated move to enhance national security and project power, even at the risk of international condemnation.

Economic motives are equally compelling. Colonial powers like Britain and France expanded their empires to access raw materials, establish new markets, and exploit cheap labor. The Dutch East India Company’s control over the Spice Islands in the 17th century is a prime example of how corporations drove territorial expansion for profit. Today, resource-rich regions like the South China Sea remain contested as nations vie for control over oil, gas, and fishing rights. This economic dimension underscores the enduring allure of territorial acquisition as a means to bolster national wealth and industrial capacity.

Ideological expansion, though less tangible, is no less powerful. The spread of religious, political, or cultural systems has often justified territorial claims. The Spanish conquest of the Americas was framed as a mission to spread Christianity, while the Soviet Union’s post-World War II expansion aimed to export communism. Even in contemporary times, nations like Turkey invoke historical and cultural ties to justify interventions in regions like Syria or northern Iraq. Such ideological drives can blur the lines between legitimate influence and imperial overreach, complicating international relations.

While territorial expansion has historically offered nations immediate benefits, it carries long-term risks. Resistance from indigenous populations, economic overextension, and international backlash can undermine the gains. For example, the British Empire’s costly efforts to suppress the Indian independence movement ultimately led to decolonization. Modern nations pursuing expansion must weigh these risks against potential rewards, recognizing that the era of overt colonialism has given way to more subtle forms of influence. Understanding the motivations and consequences of territorial expansion is crucial for navigating the complexities of global politics today.

Elgintensity's Political Leanings: Unraveling the Controversial Online Personality's Views

You may want to see also

Resistance Movements: Indigenous and local efforts to oppose and overthrow imperial rule

Imperialism, as a political and economic system, has historically involved the domination and exploitation of one nation by another, often resulting in the suppression of indigenous cultures, economies, and sovereignty. Resistance movements have emerged as a powerful counterforce, with indigenous and local populations mobilizing to reclaim their autonomy and challenge imperial rule. These movements are not monolithic; they vary in tactics, ideologies, and outcomes, but they share a common goal: liberation.

One of the most instructive examples of indigenous resistance is the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya (1952–1960). The Kikuyu people, subjected to British colonial land dispossession and forced labor, formed a clandestine movement to reclaim their ancestral lands and self-governance. Their tactics included guerrilla warfare, sabotage of colonial infrastructure, and the establishment of alternative governance systems in the forests. While the British responded with brutal suppression, including internment camps and torture, the Mau Mau’s resilience laid the groundwork for Kenya’s eventual independence in 1963. This case underscores the importance of leveraging local terrain and community networks in resistance efforts, as well as the need for international solidarity to expose imperial atrocities.

In contrast, the Zapatista Movement in Chiapas, Mexico, offers a modern, non-violent model of resistance. Emerging in 1994, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) sought to protect indigenous rights and autonomy against neoliberal policies that marginalized rural communities. Instead of outright armed conflict, the Zapatistas employed symbolic actions, such as occupying government buildings and issuing communiqués, alongside the construction of autonomous municipalities. Their strategy highlights the power of cultural preservation and political education as tools of resistance, demonstrating that opposition to imperialism need not always involve direct confrontation.

A comparative analysis of these movements reveals a critical takeaway: successful resistance requires adaptability. While the Mau Mau relied on armed struggle in a colonial context, the Zapatistas adapted to a post-colonial state by blending direct action with grassroots organizing and media outreach. Both movements, however, underscore the necessity of unity within diversity, as they mobilized broad coalitions of indigenous groups, peasants, and urban allies. For contemporary resistance efforts, this suggests that strategies must be tailored to local contexts, balancing traditional methods with innovative approaches to address evolving imperial tactics.

Practically, communities resisting imperial or neo-imperial influences today can draw from these historical lessons. Steps include: 1) Documenting and publicizing human rights violations to garner international support, 2) Strengthening local economies to reduce dependency on imperial systems, and 3) Building alliances across ethnic, regional, and ideological lines. Cautions involve avoiding internal fragmentation and remaining vigilant against co-optation by external powers. Ultimately, the legacy of these movements reminds us that resistance is not merely about overthrowing rule but about reimagining and reconstructing systems that honor indigenous sovereignty and self-determination.

Understanding Political Opportunism: Tactics, Impact, and Ethical Implications

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Imperialism is a policy or ideology of extending a country's power and influence through diplomacy or military force, often resulting in the domination of other territories, cultures, or peoples.

Imperialism involves a broader exercise of power and control, often economic or political, while colonialism specifically refers to the establishment of settlements and direct rule over a territory by an external power.

The main motivations include economic gain (access to resources and markets), political dominance, strategic military advantages, and the spread of cultural or ideological influence.

Examples include the British Empire in India, the Spanish conquest of the Americas, and the Scramble for Africa in the 19th century, where European powers divided and controlled African territories.

Long-term effects include economic exploitation, cultural erasure, political instability, and the creation of artificial borders that often lead to conflicts in post-colonial nations.