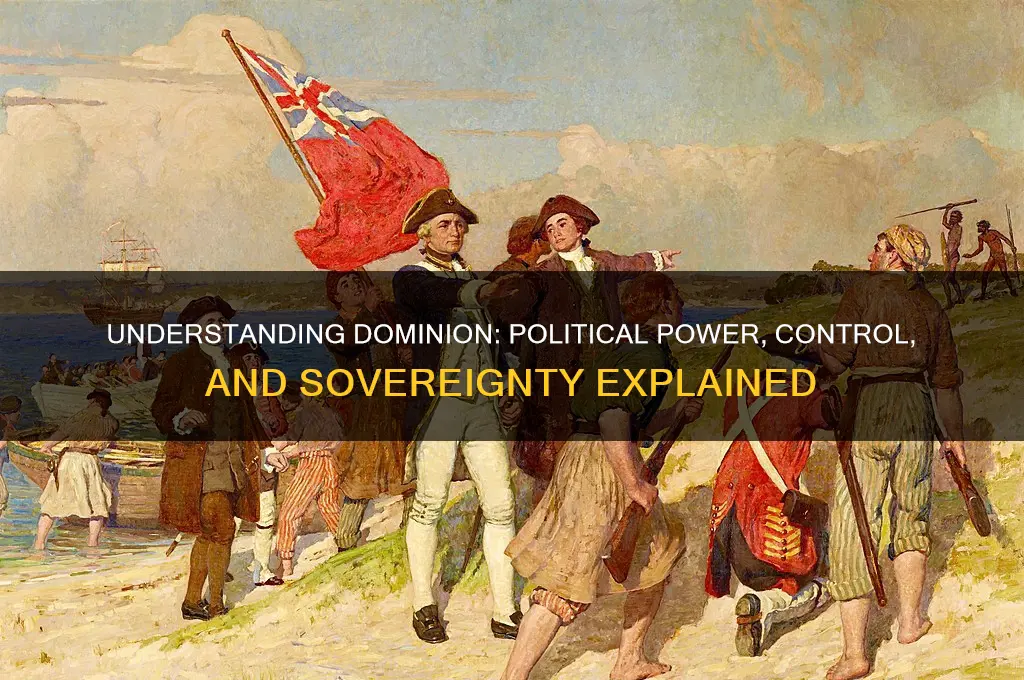

Dominion in politics refers to a status of self-governance granted to certain territories within the British Empire, allowing them to manage their internal affairs while remaining under the sovereignty of the British Crown. Established in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, dominions such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa were considered semi-independent nations with significant autonomy in domestic and foreign policy. This concept marked a pivotal shift from colonial rule to a more cooperative relationship within the Commonwealth, laying the groundwork for the modern understanding of independent nations within a shared framework of allegiance to the Crown.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A self-governing nation with a status of formal equality to other nations, yet constitutionally subordinate to a crown or parent state. |

| Historical Context | Emerged in the 19th century within the British Empire; formalized in the Balfour Declaration (1926) and the Statute of Westminster (1931). |

| Sovereignty | Possessed internal sovereignty but limited external sovereignty, often requiring approval from the parent state for foreign affairs. |

| Head of State | Shared a common monarch with the parent state (e.g., the British monarch). |

| Self-Governance | Had independent legislative, executive, and judicial systems. |

| Foreign Relations | Initially conducted through the parent state, though later dominions gained full control over their foreign policy. |

| Defense | Often relied on the parent state for defense, though some maintained their own military forces. |

| Examples | Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Ireland (pre-1949). |

| Evolution | Most dominions evolved into fully independent republics or monarchies, severing formal ties with the British Crown. |

| Legal Status | Recognized as "autonomous communities within the British Empire" until full independence. |

| Symbolism | Retained symbols of the parent state (e.g., flags, anthems) initially, later adopting unique national symbols. |

| Current Relevance | The term is largely historical; modern Commonwealth nations are fully independent. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Origins: Dominion's roots in British Empire, evolving from colonies to semi-independent states

- Legal Status: Dominions as self-governing entities under the Crown's nominal authority

- Key Examples: Canada, Australia, and others as prominent historical Dominion examples

- Balfour Declaration: 1926 statement recognizing Dominions as equal, autonomous nations

- Transition to Commonwealth: Dominions' shift to independent republics or Commonwealth realms

Historical Origins: Dominion's roots in British Empire, evolving from colonies to semi-independent states

The concept of Dominion emerged as a pivotal innovation within the British Empire, marking a transition from rigid colonial rule to a more nuanced system of semi-independent states. This evolution began in the late 19th century, as Britain sought to reconcile its imperial ambitions with the growing demands for self-governance in its settler colonies. The term "Dominion" itself was first formally used in the Constitution Act of 1867, which established Canada as the first Dominion, signaling a shift from subjugation to partnership within the empire.

Analytically, the Dominion status was a strategic compromise. It granted colonies like Canada, Australia, and New Zealand significant autonomy in domestic affairs while retaining British control over foreign policy and defense. This arrangement allowed these territories to develop their own identities and institutions, fostering a sense of national pride without severing ties to the Crown. For instance, Canada’s ability to enact its own criminal code in 1892 exemplified the practical independence Dominions enjoyed, even as they remained constitutionally linked to Britain.

Instructively, the transformation from colony to Dominion followed a clear pattern. Colonies had to meet specific criteria, such as a stable population of European descent, a functioning economy, and a demonstrated capacity for self-governance. Once these conditions were met, Britain would grant Dominion status through constitutional acts, as seen in the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910. This process was not merely administrative but symbolic, reflecting a redefinition of imperial relationships based on cooperation rather than coercion.

Persuasively, the Dominion system was a masterstroke of imperial diplomacy. By offering colonies a degree of autonomy, Britain mitigated the risk of rebellion and secession, as seen in the absence of major independence movements in Dominions compared to other colonial powers. Moreover, it solidified the empire’s influence by embedding British values and institutions in these emerging nations, ensuring long-term cultural and political alignment. This approach contrasts sharply with the more exploitative models of other European empires, which often led to violent decolonization struggles.

Comparatively, the Dominion model stands out as a unique experiment in imperial governance. Unlike the French or Spanish empires, which maintained tight control over their colonies, Britain’s approach allowed for the organic growth of nation-states within its orbit. This flexibility enabled Dominions to evolve into fully independent countries within the Commonwealth, as evidenced by the Statute of Westminster in 1931, which formally recognized their sovereignty. The legacy of this system is still visible today in the shared legal frameworks, cultural ties, and cooperative relationships among former Dominions.

Descriptively, the Dominion era was characterized by a blend of tradition and innovation. While the British monarch remained the symbolic head of state, Dominion governments exercised real power, crafting policies that reflected local needs and aspirations. This duality is vividly illustrated in the Balfour Declaration of 1926, which declared Dominions as "autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another." Such declarations underscored the evolving nature of imperial authority, transforming it from a hierarchy of dominance to a network of equals.

Mastering Debate: Effective Strategies to Dismantle Political Disadvantages

You may want to see also

Legal Status: Dominions as self-governing entities under the Crown's nominal authority

The concept of Dominions within the British Empire represents a pivotal evolution in colonial governance, marking the transition from direct imperial rule to self-governing entities under the Crown’s nominal authority. This legal status, formalized in the Balfour Declaration of 1926 and the Statute of Westminster in 1931, granted Dominions like Canada, Australia, and New Zealand autonomy in domestic and foreign affairs while maintaining symbolic allegiance to the British monarch. This framework allowed these nations to function as independent states, yet their constitutional ties to the Crown ensured a shared identity within the Commonwealth.

Analyzing the legal structure, Dominions were not merely colonies but sovereign states with the power to legislate, govern, and conduct international relations independently. The Crown’s authority was largely ceremonial, exercised through a Governor-General appointed on the advice of the Dominion’s government. This duality—self-governance coupled with nominal royal oversight—created a unique political model that balanced national autonomy with imperial unity. For instance, Canada’s ability to sign treaties independently after 1931 exemplified this shift, though the monarch remained the formal head of state.

A comparative perspective highlights the distinction between Dominions and other colonial territories. Unlike protectorates or crown colonies, which were directly administered by the British government, Dominions enjoyed full legislative freedom. This status was not static; it evolved through constitutional milestones, such as the 1926 Imperial Conference, which declared Dominions as "autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another." This evolution underscores the Dominions’ role as pioneers of modern Commonwealth nations.

Practically, the Dominion model offered a blueprint for decolonization, allowing nations to transition from colonial rule to independence without severing all ties with Britain. For emerging nations today, this historical framework provides a lesson in negotiating sovereignty while retaining cultural and institutional links. However, it also serves as a caution: the nominal authority of the Crown could sometimes blur the lines of true independence, as seen in early Dominion struggles to assert full control over foreign policy.

In conclusion, the legal status of Dominions as self-governing entities under the Crown’s nominal authority was a groundbreaking political innovation. It redefined the relationship between colonies and the imperial center, offering a middle ground between dependence and complete separation. This model not only shaped the histories of nations like Canada and Australia but also influenced global discussions on sovereignty, autonomy, and post-colonial identity. Its legacy endures in the modern Commonwealth, where member states continue to navigate the complexities of shared heritage and independent governance.

Is Masculinity Politically Incorrect? Debunking Myths and Redefining Manhood

You may want to see also

Key Examples: Canada, Australia, and others as prominent historical Dominion examples

The term "Dominion" in politics historically refers to a self-governing nation within the British Empire, maintaining allegiance to the Crown while exercising significant autonomy. Among the most prominent examples are Canada and Australia, whose evolution from colonies to Dominions shaped modern Commonwealth nations. Canada, achieving Dominion status in 1867, became a model for federated governance, balancing provincial and federal powers. Australia, federated in 1901, mirrored this structure, though its path to full sovereignty was more gradual. These nations exemplify the Dominion system’s ability to foster unity under a shared crown while nurturing distinct national identities.

Consider Canada’s journey as a case study in pragmatic nation-building. The British North America Act of 1867 not only granted Dominion status but also established a parliamentary system with a Governor General representing the Crown. This framework allowed Canada to navigate complex issues like French-English duality and territorial expansion. For instance, the creation of provinces like Manitoba in 1870 and Alberta in 1905 demonstrated how Dominion status facilitated regional autonomy within a unified nation. Practical tip: When studying federal systems, examine how Canada’s Dominion model influenced its ability to integrate diverse populations and regions.

Australia’s Dominion experience contrasts with Canada’s in its emphasis on cultural and legal evolution. While Canada’s Dominion status was a direct grant, Australia’s federation in 1901 was the culmination of decades of negotiation among its colonies. The Australian Constitution, drafted during this period, reflects a unique blend of British traditions and local aspirations. Notably, the 1926 Imperial Conference affirmed Australia’s legal equality with the UK, though full sovereignty came later with the Australia Act of 1986. This gradual shift underscores the Dominion system’s flexibility, allowing nations to mature politically at their own pace.

Beyond Canada and Australia, other Dominions like New Zealand and South Africa illustrate the system’s adaptability. New Zealand, achieving Dominion status in 1907, became a pioneer in social reforms, such as women’s suffrage in 1893. South Africa, a Dominion from 1910 to 1961, highlights the system’s limitations, as its racial policies diverged sharply from Commonwealth ideals, leading to its departure. These examples reveal how Dominion status could both empower and constrain nations, depending on their internal dynamics and global context.

In analyzing these historical Dominions, a key takeaway emerges: the Dominion model served as a transitional phase between colonialism and full independence. It provided a framework for self-governance while maintaining ties to a shared imperial heritage. For modern nations seeking autonomy, studying these examples offers insights into balancing tradition and innovation. Caution: Avoid romanticizing the Dominion era; its successes were often accompanied by struggles over identity, sovereignty, and equality. Instead, focus on its practical lessons for fostering unity in diversity.

Is Politics Nation Cancelled? Analyzing the Show's Current Status and Future

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Balfour Declaration: 1926 statement recognizing Dominions as equal, autonomous nations

The Balfour Declaration of 1926 marked a pivotal shift in the British Empire's relationship with its Dominions, redefining their status from subordinate colonies to equal, autonomous nations. This statement, agreed upon at the Imperial Conference, formally recognized that Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the Irish Free State were no longer dependent territories but independent members of the British Commonwealth. The declaration explicitly stated that they were "equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the Crown." This was a radical departure from earlier imperial policies, laying the groundwork for the modern Commonwealth of Nations.

To understand the significance of this declaration, consider the context of the early 20th century. The aftermath of World War I had heightened nationalistic sentiments within the Dominions, and their contributions to the war effort had bolstered their claims for greater autonomy. The Balfour Declaration was not merely a symbolic gesture but a legal and political acknowledgment of their maturity as nations. It clarified that the British government could not legislate for the Dominions without their consent, effectively ending any residual imperial control over their internal affairs. This principle of equality was further solidified in the Statute of Westminster in 1931, which formally granted the Dominions legislative independence.

From a practical standpoint, the Balfour Declaration had far-reaching implications for international relations and governance. It allowed the Dominions to conduct their own foreign policies, negotiate treaties, and participate independently in international organizations. For instance, Canada began to assert its sovereignty in global affairs, such as signing the Treaty of Versailles independently in 1919. This newfound autonomy also meant that the Dominions could diverge from British policies when their interests differed, as seen in South Africa's departure from the Commonwealth in 1961 due to its apartheid policies. The declaration thus served as a blueprint for decolonization, demonstrating how imperial powers could transition from dominance to partnership.

Critics might argue that the Balfour Declaration was more about preserving British influence than genuine emancipation. While the Dominions gained formal equality, their ties to the Crown and cultural affinities with Britain ensured that the empire's legacy persisted. However, this perspective overlooks the transformative nature of the declaration. It was a voluntary agreement among nations, not a decree imposed by an imperial authority. By recognizing the Dominions as equals, Britain set a precedent for peaceful decolonization, contrasting sharply with the violent struggles seen in other empires. This approach allowed for a gradual, negotiated transition to independence, preserving mutual respect and cooperation.

In conclusion, the Balfour Declaration of 1926 was a landmark in the evolution of dominion status, redefining the relationship between Britain and its former colonies. It was not just a statement of equality but a practical framework for autonomous governance and international engagement. By acknowledging the Dominions as independent nations, Britain paved the way for a new era of Commonwealth relations based on mutual respect and shared values. This declaration remains a testament to the power of diplomacy in transforming imperial structures into partnerships of equals.

Do Political Candidates Memorize Speeches? Unveiling Campaign Rhetoric Secrets

You may want to see also

Transition to Commonwealth: Dominions' shift to independent republics or Commonwealth realms

The evolution of Dominions within the British Empire marks a pivotal shift in global political structures, as these self-governing territories transitioned into either independent republics or Commonwealth realms. This transformation reflects broader trends in decolonization and the redefinition of sovereignty in the 20th century. Dominions, initially established as semi-autonomous states under the British Crown, gradually asserted their independence through constitutional reforms, culminating in the Statute of Westminster in 1931. This statute granted Dominions full legislative independence, though many retained symbolic ties to the British monarchy. The subsequent decades saw nations like India, Pakistan, and South Africa severing these ties entirely, becoming republics, while others, such as Canada and Australia, maintained the monarch as head of state, evolving into Commonwealth realms.

To understand this transition, consider the steps nations took to assert their sovereignty. First, constitutional amendments were enacted to redefine the role of the British Crown, often replacing the monarch with a ceremonial president or governor-general. Second, referendums were held in some countries, such as South Africa in 1960 and Australia in 1999, to gauge public sentiment on becoming a republic. Third, legal frameworks were established to ensure a smooth transition, preserving stability while asserting independence. For instance, India’s transition in 1950 involved adopting a new constitution that retained the Commonwealth membership but removed the British monarch as head of state. These steps highlight the deliberate and structured nature of the shift from Dominion status.

A comparative analysis reveals distinct motivations behind the choice to become a republic or remain a Commonwealth realm. Republics often sought to sever all colonial ties, symbolizing complete political and cultural independence. For example, Ireland’s transition in 1949 was driven by a desire to distance itself from British influence, while South Africa’s move in 1961 was tied to apartheid policies and international isolation. In contrast, Commonwealth realms prioritized continuity and pragmatic considerations, such as maintaining access to Commonwealth markets and institutions. Canada’s decision to retain the monarchy, for instance, was influenced by its bilingual and multicultural identity, which found a unifying symbol in the Crown. These choices underscore the interplay between historical context, national identity, and strategic interests.

Practical tips for understanding this transition include studying key constitutional documents, such as the Statute of Westminster and individual nation’s independence acts, to trace the legal evolution of sovereignty. Analyzing public debates and referendums provides insight into societal attitudes toward independence and monarchy. Additionally, examining the role of Commonwealth institutions, like the Commonwealth Secretariat, helps illustrate how former Dominions maintained global connections post-transition. For educators and researchers, focusing on case studies—such as India’s republic model versus Canada’s realm model—offers a nuanced understanding of the diverse pathways nations took in redefining their political status.

In conclusion, the transition from Dominions to independent republics or Commonwealth realms exemplifies the complex interplay of legal, political, and cultural factors in the decolonization process. This shift not only redefined the relationship between former colonies and the British Empire but also reshaped global governance structures. By examining the specific steps, motivations, and outcomes of this transition, one gains a deeper appreciation for the enduring legacy of Dominions in contemporary international politics. Whether through republic or realm, these nations charted their own paths to sovereignty, leaving an indelible mark on the modern world.

Understanding Pakistan's Political Landscape: Dynamics, Challenges, and Future Prospects

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In politics, dominion refers to the sovereignty or control a state or government has over a particular territory or group of people, often implying a degree of autonomy or self-governance under a larger empire or authority.

A dominion typically enjoys more autonomy and self-governance compared to a colony. While colonies are directly ruled by the imperial power, dominions have their own governments and constitutions, though they may still owe allegiance to a common crown or authority.

Historical examples of dominions include Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa during the British Empire. These territories were self-governing but remained part of the British Commonwealth, with the British monarch as their symbolic head of state.

The formal use of the term "dominion" has largely been replaced, but the concept of autonomous territories within a larger political framework persists. Modern examples include Commonwealth realms, where countries like Canada and Australia are independent but recognize the British monarch as their head of state.

In international law, dominion refers to a state's effective control over a territory. It is a key principle in determining sovereignty and jurisdiction, often relevant in disputes over territorial claims or the legality of governance in certain areas.

![Rose's hand-book of Dominion politics, etc., etc., etc., 1886 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41qaVm0pKML._AC_UY218_.jpg)