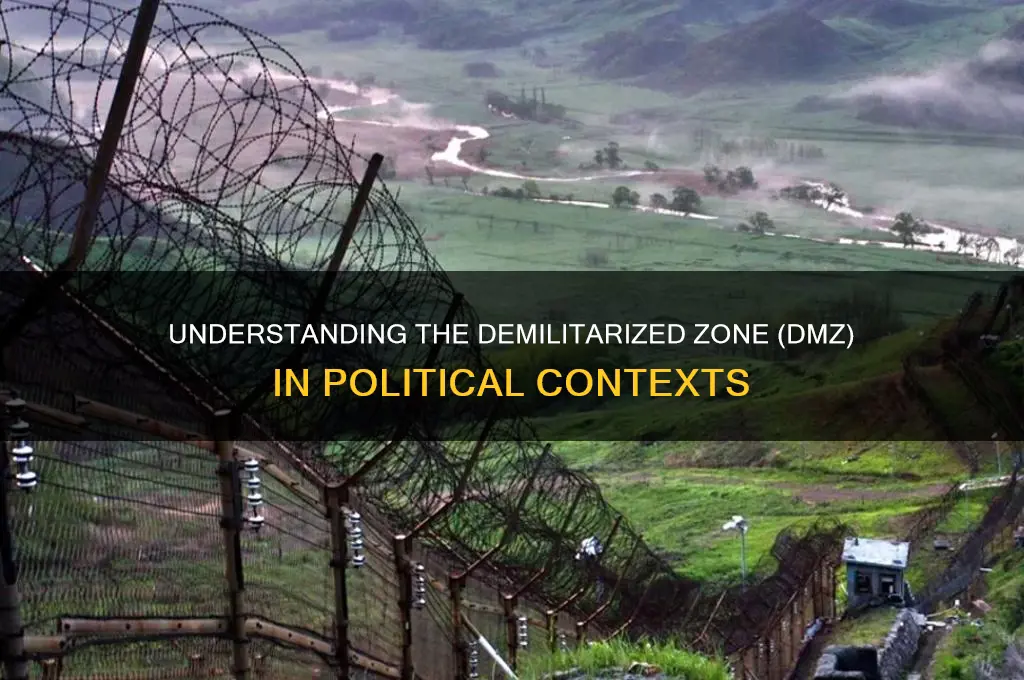

The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) in politics refers to a buffer area established between two or more hostile parties, typically as part of a ceasefire or peace agreement, where military activities and personnel are prohibited. The most well-known example is the Korean DMZ, created in 1953 to separate North and South Korea after the Korean War, serving as a physical and ideological divide between the two nations. DMZs are designed to reduce tensions, prevent direct conflict, and provide a space for diplomatic negotiations, though they often become symbols of enduring division and geopolitical standoff. Beyond Korea, DMZs have been implemented in various regions, each reflecting unique historical and political contexts, highlighting their role as both practical security measures and powerful political statements.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) is a buffer area between two or more hostile nations, free from military presence and activities. |

| Primary Purpose | To prevent direct conflict, reduce tensions, and serve as a neutral zone. |

| Legal Status | Often established through treaties, agreements, or international mediation. |

| Geographical Features | Typically a strip of land, sometimes including water bodies, with defined boundaries. |

| Military Restrictions | No military personnel, weapons, or fortifications allowed within the zone. |

| Civilian Presence | May allow limited civilian activities, depending on the agreement. |

| Monitoring and Enforcement | Often overseen by international organizations (e.g., UN) or joint commissions. |

| Examples | Korean DMZ (between North and South Korea), Green Line in Cyprus. |

| Ecological Impact | Often becomes a haven for wildlife due to lack of human interference. |

| Symbolism | Represents both division and potential for peace and reconciliation. |

| Duration | Can be temporary or permanent, depending on the political situation. |

| Economic Impact | May restrict development but can also foster tourism or conservation efforts. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- DMZ Definition: Demilitarized zone, a buffer area between nations, free from military presence, to prevent conflict

- Korean DMZ: Divides North and South Korea, established in 1953, heavily fortified border zone

- DMZ Purpose: Reduces tensions, prevents direct confrontation, and serves as a neutral territory

- Global DMZs: Examples include Cyprus, Israel-Syria, and Kashmir, each with unique political contexts

- DMZ Challenges: Smuggling, espionage, and occasional military incidents despite demilitarized status

DMZ Definition: Demilitarized zone, a buffer area between nations, free from military presence, to prevent conflict

A demilitarized zone (DMZ) is a geopolitical concept designed to prevent conflict by creating a buffer area between nations, entirely free from military presence. This zone acts as a physical and symbolic barrier, reducing the likelihood of accidental or intentional escalation. For instance, the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), established in 1953, separates North and South Korea along the 38th parallel, stretching 160 miles long and 2.5 miles wide. It is one of the most heavily fortified borders in the world, yet its core purpose remains the absence of military forces within its boundaries, serving as a stark reminder of the fragile peace it maintains.

Establishing a DMZ requires careful negotiation and clear boundaries, both physical and legal. The process involves delineating the zone’s exact coordinates, agreeing on enforcement mechanisms, and ensuring compliance from all parties. For example, the DMZ between Israel and Syria in the Golan Heights, monitored by the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF), relies on international oversight to maintain its demilitarized status. Practical steps include removing military installations, prohibiting armed personnel, and implementing surveillance systems to verify adherence. However, challenges arise when nations interpret agreements differently or when external actors attempt to exploit the zone’s neutrality.

The effectiveness of a DMZ hinges on mutual trust and shared commitment to peace. While it reduces the risk of direct military confrontation, it does not eliminate tensions entirely. The Korean DMZ, for instance, has seen sporadic incidents, such as the 1976 Axe Murder Incident, highlighting the zone’s limitations. To maximize its utility, nations must complement DMZs with diplomatic efforts, such as regular dialogue and confidence-building measures. For policymakers, the key takeaway is that a DMZ is not a solution in itself but a tool that requires ongoing maintenance and political will to succeed.

Comparatively, DMZs differ from neutral zones or peacekeeping areas in their strict prohibition of military activity. Neutral zones, like the Saudi-Iraqi Neutral Zone (1922–1991), allowed limited civilian activity but maintained a demilitarized status. In contrast, DMZs are often devoid of human presence, serving solely as a buffer. This distinction underscores the DMZ’s unique role in conflict prevention: it is not about shared use but about creating a void where conflict cannot thrive. For nations considering a DMZ, understanding this difference is crucial to setting realistic expectations and designing effective agreements.

In practice, DMZs can have unintended consequences, both positive and negative. On one hand, they preserve ecosystems by limiting human interference, as seen in the Korean DMZ, which has become a haven for rare species. On the other hand, they can perpetuate division, as communities separated by these zones often struggle to reconnect. For instance, families divided by the Korean DMZ have faced decades of separation. Policymakers must weigh these outcomes, ensuring that the benefits of conflict prevention do not come at the expense of long-term societal healing. A well-designed DMZ balances security with the potential for future reconciliation.

Understanding the Role and Function of a Political Cabinet

You may want to see also

Korean DMZ: Divides North and South Korea, established in 1953, heavily fortified border zone

The Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), stretching 160 miles across the Korean Peninsula, is one of the most heavily fortified borders in the world. Established in 1953 as part of the armistice agreement that halted the Korean War, this 2.5-mile-wide buffer zone separates North and South Korea, serving as a physical and ideological divide between two vastly different political systems. Unlike typical demilitarized zones, the Korean DMZ is anything but demilitarized; it is bristling with landmines, guard posts, and troops, making it a stark symbol of Cold War tensions that persist to this day.

Analytically, the DMZ’s existence highlights the unresolved nature of the Korean conflict. The armistice signed in 1953 was intended as a temporary measure, yet it remains the only agreement governing relations between the two Koreas. The DMZ’s heavy fortification reflects the deep mistrust and hostility between the regimes in Pyongyang and Seoul. For North Korea, the DMZ is a defensive barrier against perceived U.S. and South Korean aggression, while for South Korea, it is a critical security buffer. This mutual suspicion has prevented the DMZ from evolving into a zone of peace, despite occasional diplomatic overtures.

From a practical standpoint, the DMZ’s ecological significance is often overlooked. Decades of minimal human interference have transformed it into an unintended wildlife sanctuary, home to rare species like the red-crowned crane and the Amur leopard. Conservationists argue that the DMZ could serve as a model for how militarized zones can inadvertently protect biodiversity. However, this ecological haven is fragile, threatened by political instability and the potential for renewed conflict. Efforts to study or preserve the DMZ’s ecosystem are complicated by its militarized status, underscoring the tension between security and environmental conservation.

Comparatively, the Korean DMZ stands in stark contrast to other demilitarized zones worldwide. For instance, the DMZ between Israel and Syria in the Golan Heights is far less fortified and has seen periods of relative calm. The Korean DMZ, however, remains a flashpoint, with incidents like the 2018 inter-Korean summit offering fleeting hope for reconciliation. Unlike the Berlin Wall, which fell in 1989, the Korean DMZ endures as a physical reminder of division, shaping the identities and policies of both North and South Korea.

Persuasively, the DMZ’s continued existence raises questions about the cost of division. Economically, the DMZ hampers regional integration, preventing the flow of goods, people, and ideas. Socially, it perpetuates a narrative of fear and enmity, particularly among younger generations who have no memory of a unified Korea. Diplomatically, it serves as a barrier to meaningful dialogue, with even small steps toward cooperation often derailed by political tensions. Dismantling the DMZ would require not just demilitarization but a fundamental shift in the relationship between the two Koreas, a daunting but necessary step toward lasting peace.

Understanding Political Orderliness: Structure, Stability, and Societal Governance Explained

You may want to see also

DMZ Purpose: Reduces tensions, prevents direct confrontation, and serves as a neutral territory

A demilitarized zone (DMZ) is a geographic buffer separating hostile factions, designed to minimize conflict by creating a no-man’s-land where military activity is prohibited. Its primary purpose is to reduce tensions by physically distancing opposing forces, making spontaneous clashes less likely. For instance, the Korean DMZ, established in 1953, stretches 160 miles across the peninsula, serving as a stark reminder of the armistice that halted the Korean War. This 2.5-mile-wide strip of land, heavily fortified yet devoid of active combat, has prevented direct confrontation between North and South Korea for decades, illustrating how a DMZ acts as a pressure valve in volatile regions.

To understand its mechanism, consider a DMZ as a diplomatic airbag—it absorbs shocks before they escalate into full-scale conflict. By prohibiting military installations, weapons, and personnel within its boundaries, a DMZ eliminates the trigger points that often spark violence. For example, the Green Line in Cyprus, separating Greek and Turkish Cypriots since 1974, has allowed both sides to maintain autonomy while avoiding direct conflict. This neutral territory fosters a psychological barrier, conditioning adversaries to view the zone not as contested land but as a shared commitment to peace.

However, establishing a DMZ is not without challenges. It requires mutual agreement, often brokered by third-party mediators, and strict enforcement mechanisms. The United Nations, for instance, has played a critical role in monitoring the Korean DMZ, ensuring neither side violates its terms. Yet, even with oversight, tensions can simmer. In 2018, North and South Korea began dismantling guard posts along the DMZ as a gesture of goodwill, but such steps are fragile and dependent on political will. This highlights the DMZ’s dual nature: a tool for peace, but one that relies on continuous cooperation.

Practically, a DMZ’s effectiveness lies in its ability to serve as a neutral territory, often used for diplomatic engagements. The Joint Security Area (JSA) within the Korean DMZ, for example, has hosted numerous high-level talks, including the 2018 summit between North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and South Korean President Moon Jae-in. Such spaces allow adversaries to meet without the symbolism of crossing each other’s borders, reducing the risk of escalation. For policymakers, the lesson is clear: a DMZ is not just a physical barrier but a strategic framework for dialogue.

In conclusion, a DMZ’s purpose—reducing tensions, preventing direct confrontation, and serving as neutral territory—is both practical and symbolic. It transforms contested land into a shared responsibility, offering a breathing space for diplomacy. While not a permanent solution, it buys time, saves lives, and provides a foundation for potential reconciliation. As global conflicts persist, the DMZ model remains a vital tool in the arsenal of conflict resolution, proving that sometimes, the absence of action—in the form of a demilitarized zone—can be the most powerful action of all.

Inflation's Dual Nature: Economic Forces vs. Political Decisions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Global DMZs: Examples include Cyprus, Israel-Syria, and Kashmir, each with unique political contexts

Demilitarized Zones (DMZs) serve as buffers between conflicting nations, often freezing tensions rather than resolving them. Globally, DMZs like those in Cyprus, Israel-Syria, and Kashmir illustrate how geography, history, and politics intertwine to create unique zones of uneasy peace. Each DMZ reflects distinct origins, management structures, and impacts on local populations, offering insights into the complexities of conflict management.

Consider Cyprus, where the Green Line divides the island into Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot sectors since 1974. Managed by the United Nations Peacekeeping Force (UNFICYP), this DMZ is both a physical barrier and a symbol of ethnic division. Unlike other DMZs, it runs through the heart of a capital city, Nicosia, disrupting daily life and economic activity. Efforts to reopen crossings, such as at Ledra Street in 2008, highlight incremental steps toward reconciliation, yet the DMZ remains a stark reminder of unresolved conflict.

In contrast, the Israel-Syria DMZ along the Golan Heights is a product of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, enforced by the UN Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF). This zone is less about ethnic division and more about strategic military disengagement. Its stability is fragile, influenced by regional dynamics like Iran’s presence in Syria and Israel’s security concerns. The DMZ’s narrow buffer zone, often just a few kilometers wide, underscores the precarious balance between deterrence and escalation.

Kashmir’s DMZ, known as the Line of Control (LoC), separates Indian- and Pakistani-administered territories, a legacy of the 1947 partition and subsequent wars. Unlike Cyprus and Israel-Syria, the LoC is not monitored by an international force, relying instead on bilateral ceasefire agreements. This absence of third-party oversight contributes to frequent violations, with cross-border shelling and skirmishes displacing civilians. The LoC exemplifies how DMZs can become flashpoints rather than stabilizers, perpetuating hostility rather than fostering peace.

These examples reveal that DMZs are not one-size-fits-all solutions. Their effectiveness depends on factors like international involvement, local governance, and the nature of the conflict. While Cyprus’s Green Line and the Israel-Syria DMZ benefit from UN oversight, Kashmir’s LoC suffers from its absence. Policymakers must tailor DMZ frameworks to specific contexts, balancing security needs with humanitarian considerations. For instance, in Cyprus, reopening crossings has eased tensions, while in Kashmir, establishing neutral monitoring could reduce violations. Understanding these nuances is crucial for transforming DMZs from zones of division into bridges for dialogue.

Are Canadians Really Polite? Unraveling the Stereotype and Cultural Truths

You may want to see also

DMZ Challenges: Smuggling, espionage, and occasional military incidents despite demilitarized status

A Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) is theoretically a buffer, a no-man’s-land where military activity is prohibited to reduce conflict. Yet, in practice, DMZs often become hotspots for smuggling, espionage, and sporadic violence. Take the Korean DMZ, the most famous example, stretching 160 miles across the peninsula. Despite its heavily fortified borders and minefields, it hasn’t stopped tunnels, drones, and even defectors from crossing. Smugglers exploit its porous nature to traffic goods, from electronics to narcotics, while spies use its obscurity to gather intelligence. Even minor incidents, like a misplaced loudspeaker or an accidental border crossing, can escalate tensions, proving that demilitarization doesn’t always mean peace.

Consider the logistical challenges of policing a DMZ. In the Korean case, both North and South Korea maintain guard posts and patrols, creating a paradox: a demilitarized zone teeming with military personnel. This duality makes it easier for illicit activities to thrive. Smugglers often bribe officials or use clandestine routes, while espionage operations leverage the zone’s restricted access to operate undetected. For instance, North Korea has been accused of using tunnels under the DMZ for infiltration, while South Korea employs advanced surveillance to monitor activity. The result? A high-stakes game of cat and mouse where the line between security and provocation is razor-thin.

To mitigate these risks, DMZ management requires a delicate balance of enforcement and diplomacy. One practical strategy is joint patrols, where both sides collaborate to monitor the zone, reducing the likelihood of unilateral aggression. Technology also plays a role: thermal cameras, motion sensors, and drones can detect unauthorized activity without escalating tensions. However, even these measures aren’t foolproof. Smugglers adapt by using decoys or operating under cover of darkness, while spies exploit technological gaps. The takeaway? A DMZ’s effectiveness hinges on mutual trust and consistent enforcement—two elements often in short supply in politically charged regions.

Finally, the occasional military incidents in DMZs highlight their inherent fragility. In 2018, a North Korean soldier defected by crossing the Joint Security Area, sparking a shootout. Such events underscore how even a single individual can destabilize the zone. For policymakers, the lesson is clear: demilitarization alone isn’t enough. Comprehensive agreements on border management, transparency, and conflict resolution mechanisms are essential. Without these, a DMZ risks becoming a stage for covert operations and accidental conflicts rather than a barrier to peace. In the end, the challenge isn’t just maintaining a demilitarized zone—it’s ensuring it serves its purpose without becoming a liability.

Understanding Political Conditions: Dynamics, Influences, and Societal Impacts Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

DMZ stands for Demilitarized Zone, which is a buffer area between two or more countries, typically established to prevent military conflict and serve as a neutral zone.

The most famous DMZ is located on the Korean Peninsula, separating North Korea and South Korea. It was established in 1953 after the Korean War Armistice Agreement.

The primary purpose of a DMZ is to reduce tensions and prevent direct military confrontation between conflicting nations by creating a neutral, non-militarized buffer zone.

Yes, DMZs typically have strict rules, such as prohibiting military activities, weapons, and sometimes civilian access, to maintain their neutral and non-combative status.