Cracking in politics refers to a gerrymandering technique where a dominant political party dilutes the voting power of the opposing party by spreading its supporters across multiple districts. This strategy ensures that the opposing party’s voters are in the minority in each district, effectively preventing them from winning any seats despite having a significant overall presence. Cracking is often used to minimize the influence of minority or opposition groups and solidify the majority party’s control over legislative bodies. It raises ethical and legal concerns, as it undermines the principle of fair representation and distorts the democratic process.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A strategy used in redistricting to dilute the voting power of a specific group by spreading their voters across multiple districts, making it harder for them to achieve a majority in any single district. |

| Purpose | To reduce the electoral influence of a particular demographic, political party, or interest group. |

| Target Groups | Often targets racial, ethnic, or political minorities to minimize their representation. |

| Effect on Representation | Decreases the likelihood of the targeted group electing representatives of their choice. |

| Legal Considerations | Can be challenged under the Voting Rights Act (VRA) and other anti-discrimination laws if it disproportionately affects minority groups. |

| Examples | Splitting urban areas with high concentrations of Democratic voters into multiple Republican-leaning districts. |

| Contrast with Packing | While cracking disperses voters, packing concentrates them into a single district to limit their influence elsewhere. |

| Recent Cases | Used in states like Texas, North Carolina, and Ohio during the 2020 redistricting cycle, leading to legal challenges. |

| Public Perception | Widely criticized as a form of gerrymandering that undermines fair representation and democratic principles. |

| Remedies | Courts may order redistricting to undo cracking, and some states use independent commissions to reduce partisan manipulation. |

Explore related products

$14.24 $22.99

$14.99 $14.95

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Origins: Brief history and meaning of cracking in political contexts, especially gerrymandering

- Purpose and Effects: How cracking dilutes voting power of specific groups in elections

- Legal Challenges: Court cases and laws addressing cracking as a political tactic

- Examples in Practice: Real-world instances of cracking in U.S. and global politics

- Countermeasures: Strategies and reforms to prevent or mitigate cracking in redistricting

Definition and Origins: Brief history and meaning of cracking in political contexts, especially gerrymandering

Cracking in politics refers to a specific tactic within the broader practice of gerrymandering, where the goal is to dilute the voting power of a particular group by spreading its members across multiple districts. This strategy ensures that the targeted group becomes a minority in each district, effectively minimizing its ability to influence election outcomes. Unlike "packing," which concentrates voters into a single district to limit their broader impact, cracking disperses them to diminish their collective voice. The origins of this practice can be traced back to early American political history, where redistricting was often manipulated to favor certain political interests. However, it gained prominence in the 20th century as political parties and incumbents sought to secure electoral advantages through precise demographic engineering.

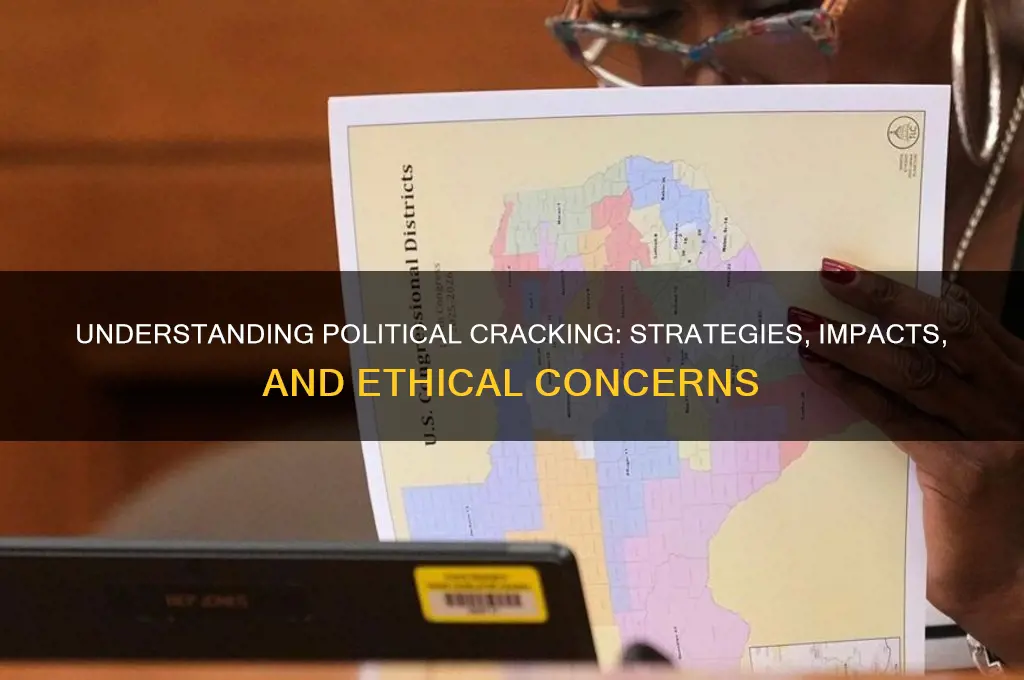

To understand cracking, consider its mechanics: imagine a city with a significant population of young, progressive voters concentrated in one area. By redrawing district lines to split this group into several districts, each with a conservative majority, their voting power is effectively neutralized. This method has been employed in states like North Carolina and Ohio, where redistricting maps have been challenged in court for disproportionately targeting minority or politically aligned groups. The 2019 *Rucho v. Common Cause* Supreme Court case highlighted the challenges of addressing partisan gerrymandering, as the Court ruled that such claims were beyond the scope of federal judicial review, leaving states to regulate the practice.

The historical roots of cracking are intertwined with the evolution of gerrymandering itself. The term "gerrymander" dates back to 1812, when Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry approved a redistricting plan that created a district resembling a salamander, favoring his Democratic-Republican Party. While early gerrymandering was often crude and visually obvious, modern cracking relies on sophisticated data analytics and mapping software to achieve surgical precision. This technological advancement has made it easier to identify and disperse specific voter groups, often with minimal public scrutiny. For instance, the 2010 redistricting cycle saw widespread use of cracking to dilute the influence of urban and minority voters, solidifying Republican control in key states.

A critical takeaway from the history and practice of cracking is its role in undermining democratic representation. By systematically diluting the voting power of specific groups, cracking exacerbates political polarization and reduces the incentive for elected officials to address the needs of marginalized communities. Practical steps to combat this include advocating for independent redistricting commissions, as seen in states like California and Arizona, which remove the process from direct partisan control. Additionally, public awareness campaigns and legal challenges remain essential tools in exposing and challenging cracking practices. While the Supreme Court’s stance limits federal intervention, state-level reforms and grassroots efforts offer pathways to mitigate its impact.

Cognitive Artifacts and Power: Exploring the Political Implications of Tools

You may want to see also

Purpose and Effects: How cracking dilutes voting power of specific groups in elections

Cracking, a gerrymandering technique, surgically divides concentrations of voters from a specific group across multiple districts to dilute their collective influence. Imagine a city with a strong Democratic-leaning minority population. Cracking would carve this population into several Republican-majority districts, ensuring their votes are spread too thin to elect a representative of their choice in any single district.

This strategy, often employed by the party in power during redistricting, effectively silences the voice of targeted groups.

The effects of cracking are insidious. It diminishes the ability of minority groups to elect representatives who reflect their interests and values. This underrepresentation translates to policies that may neglect or actively harm these communities. For instance, a cracked Latino community might struggle to secure funding for bilingual education or immigration reform.

Consider the 2010 redistricting in North Carolina. The Republican-controlled legislature cracked African-American voters across multiple districts, significantly reducing their ability to elect Democratic representatives. This resulted in a congressional delegation that was disproportionately Republican, despite the state's relatively even partisan divide.

Combating cracking requires vigilance and reform. Transparency in the redistricting process, the use of independent commissions, and stricter legal standards for fairness are crucial. Voters must demand accountability and push for systems that prioritize fair representation over partisan gain.

Are All Acts Political? Exploring the Intersection of Life and Power

You may want to see also

Legal Challenges: Court cases and laws addressing cracking as a political tactic

Cracking, the practice of diluting the voting power of a specific group by spreading their population across multiple districts, has faced significant legal scrutiny. Courts have grappled with the constitutionality of this tactic, often weighing it against the Equal Protection Clause and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Landmark cases like *Shaw v. Reno* (1993) and *Cooper v. Harris* (2017) have set precedents for evaluating whether cracking constitutes racial gerrymandering, a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. These cases highlight the delicate balance between political strategy and constitutional rights, as judges must determine when cracking crosses the line from legitimate redistricting to unlawful discrimination.

To address cracking, legal challenges often focus on proving discriminatory intent or effect. Plaintiffs must demonstrate that the redistricting process was motivated by a desire to diminish the influence of a particular racial or political group. For instance, in *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019), the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts lack jurisdiction to decide partisan gerrymandering claims, leaving such cases to state courts and legislatures. However, state-level lawsuits, like those in North Carolina and Pennsylvania, have successfully challenged cracking by arguing that it violates state constitutional provisions guaranteeing free and fair elections. These cases underscore the importance of local legal frameworks in combating this tactic.

Legislative efforts to curb cracking have also gained traction, particularly through the enforcement of preclearance requirements under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Before its partial invalidation in *Shelby County v. Holder* (2013), this provision required jurisdictions with a history of discrimination to obtain federal approval for redistricting plans. While preclearance is no longer universally applicable, states like California have adopted independent redistricting commissions to reduce partisan manipulation, including cracking. Such commissions aim to prioritize fairness and transparency, though their effectiveness varies depending on their structure and funding.

Practical tips for legal advocates include gathering comprehensive demographic data to illustrate the disproportionate impact of cracking on minority communities. Collaborating with civil rights organizations can amplify the reach and credibility of legal challenges. Additionally, leveraging public opinion through grassroots campaigns can pressure lawmakers to enact reforms. For individuals, staying informed about redistricting processes in their state and participating in public hearings can help ensure their voices are heard. While cracking remains a persistent issue, a combination of litigation, legislation, and civic engagement offers a pathway to more equitable representation.

Effective Political Advocacy: Strategies to Raise Concerns and Drive Change

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Examples in Practice: Real-world instances of cracking in U.S. and global politics

In the 2010s, North Carolina’s legislature redrew congressional maps to dilute African American voting power by splitting predominantly Black precincts across multiple districts. This "cracking" strategy reduced the influence of minority voters, ensuring Republican majorities in 10 out of 13 districts, despite Democrats winning roughly half the statewide vote. The U.S. Supreme Court initially struck down the maps as unconstitutional racial gerrymandering in *Cooper v. Harris* (2017), but the practice persists in other states, highlighting how cracking undermines democratic representation.

Globally, Hungary’s Fidesz party under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán employed cracking in 2011 by fragmenting opposition strongholds in Budapest and other urban centers. By redistributing these voters into larger, rural districts dominated by Fidesz supporters, the party secured a supermajority in parliament with less than 50% of the popular vote. This tactic not only solidified Orbán’s authoritarian grip but also marginalized opposition voices, illustrating how cracking can be weaponized to entrench political power.

In the U.S., Arizona’s 2021 redistricting process cracked Phoenix’s growing Latino electorate by dividing the city into multiple districts, pairing these voters with predominantly white, Republican-leaning suburbs. This dilution weakened the impact of Latino voters, who tend to favor Democratic candidates. While Arizona’s Independent Redistricting Commission aimed to reduce partisan bias, critics argue that cracking still occurred, demonstrating the challenges of balancing demographic shifts with fair representation.

To combat cracking, activists and policymakers can adopt three practical steps: first, advocate for independent redistricting commissions to minimize partisan manipulation; second, leverage data analytics to identify and challenge cracked districts in court; and third, support proportional representation systems, which inherently reduce the effectiveness of cracking by allocating seats based on vote share rather than geographic boundaries. These measures, while not foolproof, offer pathways to mitigate the corrosive effects of cracking on democratic integrity.

Political Apathy's Peril: How Disengagement Threatens Democracy and Society

You may want to see also

Countermeasures: Strategies and reforms to prevent or mitigate cracking in redistricting

Cracking in redistricting dilutes the voting power of a targeted group by spreading its members across multiple districts, ensuring they never achieve a majority in any. This tactic undermines democratic representation, but several countermeasures can prevent or mitigate its effects.

Legislative Reforms: Strengthening Legal Frameworks

One effective strategy is to enact and enforce laws that explicitly prohibit cracking. States can adopt criteria requiring districts to respect communities of interest, ensuring minority groups are not artificially dispersed. For instance, California’s redistricting process, guided by an independent commission, prioritizes keeping communities intact, reducing opportunities for cracking. Federal legislation, such as the Voting Rights Act (VRA), historically provided preclearance requirements for states with a history of discrimination, though its effectiveness has been weakened by recent Supreme Court decisions. Restoring and expanding the VRA’s protections could reestablish critical safeguards against cracking.

Independent Commissions: Removing Partisan Influence

Partisan control over redistricting often incentivizes cracking. Establishing independent, nonpartisan commissions to draw district lines can eliminate this conflict of interest. Arizona’s Independent Redistricting Commission, for example, has successfully minimized gerrymandering by prioritizing compactness and community cohesion over partisan advantage. Such commissions typically include diverse representation, ensuring minority voices are heard in the process. While not foolproof, this approach reduces the likelihood of cracking by depoliticizing the process.

Transparency and Public Engagement: Empowering Citizens

Transparency in redistricting can deter cracking by holding mapmakers accountable. Public hearings, accessible data, and user-friendly mapping tools allow citizens to scrutinize proposed districts and identify cracking attempts. In Michigan, a 2018 ballot initiative created an independent commission with strict transparency requirements, including live-streamed meetings and public comment periods. This model empowers voters to challenge maps that dilute their representation, fostering a more democratic process.

Judicial Oversight: Enforcing Fairness

Courts play a crucial role in combating cracking by striking down unconstitutional maps. Landmark cases like *Shaw v. Reno* and *Rucho v. Common Cause* highlight the judiciary’s power to intervene, though outcomes vary by jurisdiction. State courts, interpreting their own constitutions, have sometimes offered stronger protections than federal courts. For instance, Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court invalidated a cracked map in 2018, redrawing it to better reflect voter demographics. Litigation remains a vital tool, but it is reactive; proactive reforms are equally essential.

Technological Solutions: Leveraging Data and Algorithms

Advances in technology offer new ways to detect and prevent cracking. Open-source mapping tools, such as Dave’s Redistricting App, enable citizens and advocacy groups to analyze proposed districts for fairness. Algorithmic models can generate thousands of maps, demonstrating that cracking is a choice, not a necessity. In North Carolina, a court-ordered redrawing process used such tools to create fairer districts. While technology is not a panacea, it provides evidence and transparency to counter manipulative practices.

By combining legislative reforms, independent commissions, public engagement, judicial oversight, and technological tools, states can create robust defenses against cracking. These measures not only protect minority voting rights but also strengthen the integrity of democratic institutions.

Is a Half Bow Polite? Etiquette Explained for Modern Manners

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cracking is a gerrymandering technique where a voting group is spread across multiple districts to dilute their influence and prevent them from achieving a majority in any single district.

While cracking spreads a voting group across districts to weaken their impact, packing concentrates them into a single district to minimize their influence in other areas.

The purpose of cracking is to reduce the political power of a specific group, often a minority or opposition party, by ensuring they cannot win enough seats to affect legislative outcomes.

The legality of cracking varies by jurisdiction. In some places, it is considered a form of unconstitutional discrimination, while in others, it may be allowed if it does not violate specific legal standards.