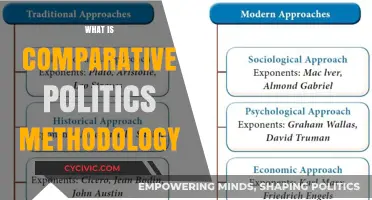

Comparative politics is an essential subfield of political science that focuses on the systematic study and comparison of political systems, institutions, and processes across different countries and regions. A comparative politics class typically explores how governments function, how policies are formulated, and how political behaviors vary globally. Students in this course examine key concepts such as democratization, authoritarianism, political culture, and state-society relations, often using case studies to analyze similarities and differences between nations. By understanding these dynamics, the class aims to provide insights into the complexities of global politics, fostering critical thinking and a deeper appreciation for the diversity of political structures worldwide.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Systematic study and comparison of political systems, institutions, and processes across countries. |

| Focus | Cross-national analysis to identify patterns, similarities, and differences. |

| Key Themes | Democratization, political regimes, governance, policy-making, and political culture. |

| Methodologies | Quantitative (statistical analysis), qualitative (case studies), and mixed methods. |

| Scope | Global, regional, or specific country comparisons. |

| Theoretical Frameworks | Structural functionalism, historical institutionalism, rational choice theory, etc. |

| Goals | Understand political phenomena, test theories, and inform policy-making. |

| Skills Developed | Critical thinking, data analysis, cross-cultural understanding, and research skills. |

| Common Topics | Elections, political parties, legislatures, judiciaries, and civil society. |

| Relevance | Provides insights into global political trends and challenges. |

| Interdisciplinary Links | Sociology, economics, history, and international relations. |

| Challenges | Data availability, cultural biases, and complexity of cross-national comparisons. |

| Career Applications | Academia, policy analysis, diplomacy, journalism, and international organizations. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Political Systems Comparison: Analyzing structures, processes, and institutions across different countries

- Democratization Studies: Examining transitions to democracy and challenges in diverse contexts

- Political Culture: Exploring values, beliefs, and norms shaping political behavior globally

- Comparative Political Economy: Studying state-market relations and policy impacts across nations

- Conflict and Governance: Investigating causes, management, and resolution of political conflicts

Political Systems Comparison: Analyzing structures, processes, and institutions across different countries

Comparative politics classes often begin by examining the foundational elements of political systems: structures, processes, and institutions. These components form the backbone of how governments operate, and comparing them across countries reveals both commonalities and stark contrasts. For instance, consider the legislative branch. In the United States, it’s a bicameral Congress, while in the United Kingdom, Parliament is unicameral but includes the House of Lords as a second chamber with limited power. Such structural differences influence policymaking speed, representation, and the balance of power. Analyzing these structures helps students understand why some democracies prioritize efficiency while others emphasize deliberation.

To effectively compare political systems, start by identifying key institutions and their roles. For example, the judiciary in France is highly centralized under the Court of Cassation, whereas in Germany, it’s decentralized with federal and state courts sharing authority. Next, examine processes like elections. India’s first-past-the-post system often leads to single-party dominance, while proportional representation in the Netherlands fosters coalition governments. Caution: avoid oversimplifying. Context matters—historical legacies, cultural norms, and socioeconomic factors shape these institutions and processes. Practical tip: Use case studies to illustrate how these elements interact, such as comparing the role of the presidency in Brazil and Mexico to highlight executive power variations.

A persuasive argument for studying political systems comparison is its utility in predicting outcomes and identifying best practices. For instance, analyzing healthcare systems reveals how single-payer models in Canada differ from multi-payer systems in Switzerland, with varying implications for accessibility and cost. Similarly, comparing federalism in Nigeria and India shows how power distribution affects stability and development. By dissecting these systems, students can advocate for reforms or critique existing models. However, be wary of assuming one-size-fits-all solutions. What works in Sweden might fail in South Africa due to differing political cultures and resources.

Descriptively, political systems comparison often involves creating frameworks to categorize countries. One common approach is classifying democracies as liberal, illiberal, or hybrid, based on criteria like free elections, rule of law, and civil liberties. For example, Norway scores high on all counts, while Hungary exhibits illiberal tendencies. Another framework is the presidential vs. parliamentary distinction, where the former (e.g., Brazil) often faces gridlock, while the latter (e.g., Sweden) fosters consensus. Takeaway: Frameworks provide structure but should be applied flexibly. Real-world systems rarely fit neatly into categories, and exceptions are as instructive as the rules.

Finally, a comparative analysis should always consider the dynamic nature of political systems. Institutions evolve, processes adapt, and structures shift in response to internal and external pressures. For example, the European Union’s supranational institutions challenge traditional notions of sovereignty, while digital technology is reshaping electoral processes globally. To stay relevant, comparative politics must incorporate these changes. Practical tip: Use longitudinal data to track transformations, such as the rise of populism in Western democracies or the erosion of judicial independence in some Eastern European countries. This approach ensures that comparisons remain grounded in current realities, not static snapshots.

Are Most Americans Politically Independent? Exploring the Rise of Centrism

You may want to see also

Democratization Studies: Examining transitions to democracy and challenges in diverse contexts

Democratization studies within comparative politics focus on the complex processes through which authoritarian regimes transition to democratic systems. These transitions are not uniform; they vary widely depending on historical, cultural, economic, and social contexts. For instance, the democratization of Spain in the late 1970s, following Franco’s dictatorship, involved negotiated pacts between elites, while the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 led to abrupt, often chaotic transitions across Eastern Europe. Understanding these differences requires a comparative lens, examining how factors like civil society strength, economic development, and external pressures shape outcomes.

One critical challenge in democratization is managing the legacy of authoritarianism. In countries like South Africa, truth and reconciliation commissions were employed to address past injustices without destabilizing the transition. However, in others, such as Egypt post-2011, unresolved grievances and deep political divisions hindered democratic consolidation. Scholars often analyze these cases to identify patterns: for example, successful transitions frequently involve inclusive institutions, credible elections, and protections for minority rights. Yet, even with these elements, external factors like geopolitical interests can undermine progress, as seen in U.S. and European interventions in the Middle East.

Another key area of study is the role of economic conditions in democratization. While modernization theory suggests that wealthier nations are more likely to sustain democracy, counterexamples abound. Greece, despite its economic struggles, maintained democratic institutions, whereas oil-rich states like Saudi Arabia remain authoritarian. This paradox highlights the need to consider not just GDP but also income inequality, state capacity, and the distribution of resources. Comparative analysis reveals that democracies often emerge when a growing middle class demands political representation, but this is not a guaranteed formula.

Practical takeaways from democratization studies emphasize the importance of context-specific strategies. For instance, in divided societies, power-sharing arrangements, as seen in Northern Ireland, can prevent backsliding. International actors can play a constructive role by providing technical assistance for elections or conditional aid tied to reforms, but they must avoid imposing one-size-fits-all models. Students of comparative politics should also note the risks of "democratic backsliding," where elected leaders erode checks and balances, as observed in Hungary and Turkey. These cases underscore the fragility of democracy and the need for vigilant civil society and independent media.

In conclusion, democratization studies offer a dynamic framework for understanding how and why transitions to democracy succeed or fail. By comparing diverse contexts, scholars and practitioners can identify both universal principles and context-specific challenges. This field is not just academic; it provides actionable insights for policymakers, activists, and citizens working to build and sustain democratic systems in an increasingly complex world.

Is 'Folks' Politically Incorrect? Exploring Language Sensitivity and Inclusivity

You may want to see also

Political Culture: Exploring values, beliefs, and norms shaping political behavior globally

Political culture, the deeply ingrained values, beliefs, and norms that shape how individuals and societies interact with political systems, varies dramatically across the globe. Consider the stark contrast between the civic culture of Sweden, where trust in institutions and participation in collective decision-making are high, and the more hierarchical political culture of Saudi Arabia, where authority is often centralized and dissent is less tolerated. These differences are not random; they are rooted in historical, religious, and socioeconomic factors that have evolved over centuries. Understanding these variations is crucial for anyone studying comparative politics, as they explain why certain policies succeed in one country but fail in another.

To explore political culture effectively, start by examining its three core components: cognitive orientation (knowledge and understanding of the political system), affective orientation (feelings toward the system), and evaluative orientation (judgments about its performance). For instance, in the United States, the cognitive orientation often emphasizes individualism and democratic principles, while in Japan, collective harmony and respect for authority dominate. These orientations influence everything from voter turnout to policy preferences. A practical tip for students is to analyze public opinion surveys, such as the World Values Survey, to identify patterns in political culture across countries. This data-driven approach provides concrete examples to support theoretical arguments.

One powerful way to study political culture is through comparative analysis. Take the concept of civic engagement, which varies widely based on cultural norms. In India, for example, civic engagement often takes the form of mass protests and grassroots movements, reflecting a culture that values direct action. In contrast, Switzerland’s political culture emphasizes consensus-building through frequent referendums, showcasing a preference for deliberation over confrontation. By comparing these cases, students can identify how political culture shapes not only behavior but also the very structure of political institutions. A cautionary note: avoid oversimplifying these comparisons, as political culture is deeply intertwined with other factors like economic development and historical legacies.

Finally, consider the role of generational change in shaping political culture. Younger generations often hold different values and beliefs than their predecessors, which can lead to shifts in political behavior. For instance, in many Western countries, millennials and Gen Z are more likely to prioritize issues like climate change and social justice, reflecting a cultural shift away from traditional economic concerns. To study this dynamic, track longitudinal data on generational attitudes and compare them across countries. This approach not only highlights the evolving nature of political culture but also underscores its adaptability in response to global challenges. By focusing on these specifics, students can gain a nuanced understanding of how political culture operates in the real world.

COVID-19 Divide: How the Pandemic Became a Political Battleground

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Comparative Political Economy: Studying state-market relations and policy impacts across nations

Comparative Political Economy (CPE) is the lens through which scholars examine the intricate dance between states and markets, revealing how their interplay shapes policy outcomes across diverse national contexts. This subfield of comparative politics goes beyond mere description, seeking to understand the causal mechanisms that link institutional arrangements, economic structures, and political processes to tangible policy impacts. By comparing these dynamics across countries, CPE uncovers patterns, identifies anomalies, and offers insights into the conditions under which certain policies succeed or fail.

Consider the divergent paths of healthcare reform in the United States and the United Kingdom. Both nations grapple with rising costs and inequitable access, yet their policy responses differ markedly. The U.S. relies heavily on private insurance markets, while the U.K. maintains a publicly funded National Health Service. A comparative political economy analysis would dissect the historical evolution of these systems, examining how factors such as interest group influence, electoral incentives, and ideological orientations have shaped their development. By isolating these variables, CPE provides a framework for understanding why certain policy tools—such as single-payer systems or market-based reforms—gain traction in some contexts but not others.

To engage in comparative political economy effectively, researchers must employ a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods. Case studies allow for deep dives into specific country experiences, illuminating the nuances of state-market relations. Cross-national statistical analyses, on the other hand, enable the identification of broader trends and correlations. For instance, a study might compare the relationship between labor market regulations and income inequality across 30 OECD countries, controlling for variables like GDP per capita and political regime type. Such an approach not only tests hypotheses but also generates actionable insights for policymakers seeking to emulate successful models or avoid pitfalls.

One practical takeaway from CPE is the importance of institutional context in policy design. For example, a policy that thrives in a coordinated market economy, such as Germany’s vocational training system, may falter in a liberal market economy like the United States. This underscores the need for policymakers to tailor reforms to their nation’s specific institutional landscape. CPE equips analysts with the tools to assess this compatibility, reducing the risk of policy failure. For students and practitioners alike, this means moving beyond one-size-fits-all solutions and embracing context-sensitive approaches.

Finally, comparative political economy serves as a bridge between theory and practice, offering a rigorous yet accessible framework for understanding complex policy challenges. By studying state-market relations across nations, it highlights both the diversity of global experiences and the common threads that bind them. Whether analyzing the impact of austerity measures in Southern Europe or the role of state-owned enterprises in East Asia, CPE provides a roadmap for navigating the intersection of politics and economics. For those seeking to make sense of an increasingly interconnected world, this subfield is not just an academic exercise—it’s an essential toolkit.

Is Corporate Political Speech Protected? Legal Boundaries and Free Speech Debates

You may want to see also

Conflict and Governance: Investigating causes, management, and resolution of political conflicts

Political conflicts are inherently complex, often rooted in a tangled web of historical grievances, economic disparities, and competing identities. Comparative politics offers a lens to dissect these conflicts by examining how different political systems manage or exacerbate them. For instance, federal systems like India and Nigeria face distinct challenges in balancing regional autonomy with national unity, while centralized states like China and France grapple with dissent through top-down control. Understanding these variations reveals that conflict is not merely a problem to solve but a dynamic process shaped by governance structures.

Consider the management of political conflicts, where strategies range from repression to negotiation. In Myanmar, the military junta’s brutal suppression of dissent has deepened ethnic divisions, while South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission exemplifies a restorative approach to post-apartheid conflict. Comparative analysis highlights the trade-offs: repression may quell short-term unrest but often sows seeds for future rebellion, whereas inclusive dialogue risks instability but fosters long-term reconciliation. Policymakers must weigh these options, recognizing that no single approach fits all contexts.

Resolution of political conflicts demands more than goodwill—it requires institutional innovation. Belgium’s consociational democracy, which allocates power among linguistic groups, offers a model for managing deep-seated divisions. Conversely, the collapse of Yugoslavia underscores the dangers of failing to address competing nationalisms. Practical steps for resolution include power-sharing agreements, constitutional reforms, and international mediation. For instance, the 2016 Colombia peace deal involved land reform and political participation for former rebels, though its implementation remains fraught. Such cases illustrate that resolution is an iterative process, not a one-time event.

A cautionary note: external interventions in political conflicts often complicate rather than resolve them. The 2003 Iraq War, justified as a means to establish democracy, instead unleashed sectarian violence and state fragmentation. Comparative politics teaches that local dynamics—cultural norms, power structures, and historical legacies—must guide conflict resolution efforts. International actors should prioritize supporting indigenous solutions rather than imposing foreign models.

In conclusion, studying conflict and governance through a comparative lens equips us with tools to navigate political turmoil. By analyzing diverse cases, we learn that effective conflict management hinges on understanding context, balancing short-term stability with long-term justice, and fostering inclusive institutions. This approach not only enriches academic inquiry but also informs practical strategies for building more resilient political systems.

Exploring My Political Compass: Where Do I Stand in Today’s Landscape?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Comparative Politics is a subfield of political science that involves the systematic study and comparison of political systems, institutions, processes, and outcomes across different countries or regions.

A Comparative Politics class typically covers topics such as political regimes (e.g., democracies, authoritarian systems), state formation, political parties and interest groups, elections and voting behavior, public policy, and the role of international factors in shaping domestic politics.

Comparative Politics is important because it helps us understand the diversity of political systems worldwide, identify patterns and trends, and explain why some countries are more stable, prosperous, or democratic than others. It also provides insights into global challenges and potential solutions.

In a Comparative Politics class, you will develop critical thinking, analytical, and research skills. You will learn to compare and contrast different political systems, evaluate theoretical frameworks, and apply empirical evidence to understand complex political phenomena.

A background in Comparative Politics can prepare you for careers in government, international organizations, NGOs, journalism, consulting, academia, and policy research. It provides a strong foundation for understanding global politics and making informed decisions in various professional settings.