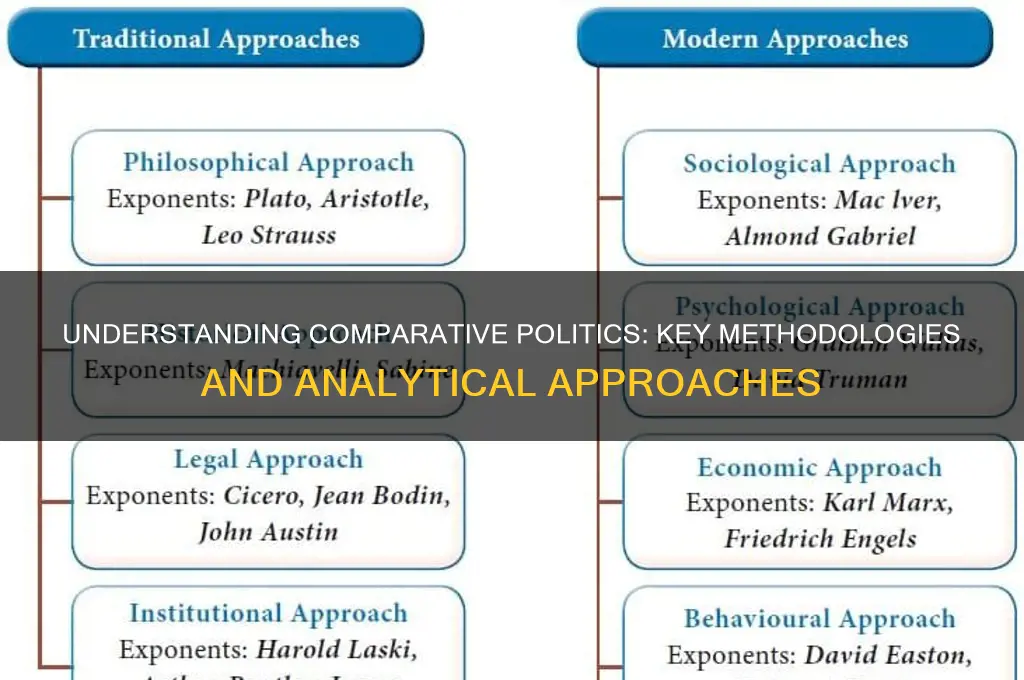

Comparative politics methodology refers to the systematic approaches and techniques used to study and analyze political systems, institutions, and behaviors across different countries or regions. It involves comparing and contrasting political phenomena to identify patterns, similarities, and differences, thereby generating insights into the underlying causes and consequences of political outcomes. This methodology encompasses a range of research designs, including case studies, small-N comparisons, large-N statistical analyses, and mixed methods, each tailored to address specific research questions. By employing rigorous theoretical frameworks and empirical data, comparative politics methodology aims to enhance our understanding of complex political dynamics, test hypotheses, and contribute to the development of generalizable theories in the field of political science.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scope | Focuses on comparing political systems, institutions, processes, and behaviors across countries or regions. |

| Approach | Empirical, theoretical, and interdisciplinary, combining qualitative and quantitative methods. |

| Key Questions | Why and how political systems differ or resemble each other; causes of political phenomena. |

| Units of Analysis | Countries, regions, political systems, institutions, policies, or actors. |

| Comparative Advantage | Allows for identifying patterns, testing theories, and drawing generalizable conclusions. |

| Methods | Case studies, most similar/most different systems designs, large-N comparisons, statistical analysis. |

| Theoretical Frameworks | Utilizes theories like rational choice, institutionalism, historical institutionalism, and structuralism. |

| Data Sources | Primary (e.g., interviews, surveys) and secondary (e.g., official records, academic literature). |

| Challenges | Ensuring comparability, avoiding ethnocentrism, and dealing with complexity of political systems. |

| Goals | Explain political outcomes, inform policy, and contribute to political theory. |

| Recent Trends | Increased focus on mixed methods, causal inference, and cross-regional comparisons. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Case Study Approach: Examines individual cases to understand political phenomena in specific contexts

- Quantitative Methods: Uses statistical analysis to test hypotheses and identify patterns in political data

- Comparative Historical Analysis: Analyzes historical events to trace political developments and causal relationships

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): Employs set-theoretic methods to compare configurations of conditions across cases

- Most Similar/Most Different Systems Design: Compares similar or dissimilar cases to isolate causal factors

Case Study Approach: Examines individual cases to understand political phenomena in specific contexts

The case study approach in comparative politics is a microscope for political scientists, allowing them to zoom in on specific instances of political phenomena and examine them in intricate detail. This method is particularly valuable when seeking to understand complex political events or processes within their unique historical, cultural, and social contexts. By focusing on individual cases, researchers can uncover nuanced insights that might be missed in broader, more generalized studies.

Unraveling Complexity: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Case Selection: The first step is critical—choosing the right case(s) to study. Researchers must identify cases that are representative of the phenomenon under investigation or offer unique insights due to their exceptional nature. For instance, a study on democratic transitions might select the case of Spain's transition from dictatorship to democracy, given its relatively smooth and successful process.

- Data Collection: This phase involves gathering a rich array of data from various sources. Researchers may analyze official documents, conduct interviews with key political figures, examine media reports, and review academic literature specific to the case. For a case study on the impact of a particular policy, one might collect data on implementation strategies, public reaction, and long-term outcomes.

- Contextual Analysis: Here, the researcher immerses themselves in the specific context of the case. This includes understanding the historical background, cultural norms, and social dynamics that could influence the political phenomenon. For example, when studying a political movement in a particular country, one must consider the nation's colonial history and its impact on contemporary political attitudes.

Cautions and Considerations:

- Generalizability: One of the primary criticisms of case studies is the challenge of generalizing findings to a broader population. Researchers must be cautious when drawing conclusions, ensuring they are specific to the case and not over-extrapolated.

- Subjectivity: The interpretive nature of case studies can introduce subjectivity. Researchers should employ rigorous methods and transparent reporting to minimize bias.

- Time and Resource Intensity: Case studies often require significant time and resources, especially when dealing with in-depth, qualitative data. This approach may not be feasible for quick turnaround research.

A Powerful Tool for Political Insight:

Despite these considerations, the case study approach remains a powerful tool in comparative politics. It enables researchers to explore the 'why' and 'how' of political events, providing a deep understanding of the intricate relationships between political actors, institutions, and their environments. By carefully selecting cases, employing rigorous methods, and acknowledging limitations, political scientists can contribute valuable, context-rich insights to the field. This method is especially useful for challenging existing theories or developing new ones, as it allows for the exploration of unique, real-world political scenarios.

Mastering Political Descriptions: A Comprehensive Guide to Clear Communication

You may want to see also

Quantitative Methods: Uses statistical analysis to test hypotheses and identify patterns in political data

Quantitative methods in comparative politics are the backbone of empirical research, offering a systematic way to test hypotheses and uncover patterns in political phenomena. By leveraging statistical analysis, researchers can transform raw data into actionable insights, whether examining the impact of economic policies on voter behavior or comparing democratic institutions across countries. For instance, a study might use regression analysis to determine if higher GDP growth rates correlate with increased electoral support for incumbent governments, controlling for variables like inflation and unemployment. This approach not only provides clarity but also allows for generalizable findings that can inform policy and theory.

To effectively employ quantitative methods, researchers must follow a structured process. First, define the research question and operationalize variables—for example, measuring "democracy" using indices like the Polity Score or V-Dem. Second, collect data from reliable sources such as the World Bank, Eurobarometer, or national census records. Third, apply statistical techniques like correlation, t-tests, or multivariate regression to analyze relationships between variables. Caution is essential: ensure data is representative, avoid overfitting models, and critically assess assumptions underlying statistical tests. For instance, using a small sample size can lead to unreliable results, while failing to account for outliers may skew findings.

One of the strengths of quantitative methods lies in their ability to handle large datasets and complex relationships. For example, cross-national studies often compare dozens of countries over multiple decades, requiring tools like panel data analysis to account for temporal and spatial dependencies. However, this power comes with trade-offs. Quantitative research can sometimes oversimplify nuanced political realities, reducing rich contexts to numerical values. To mitigate this, researchers often complement quantitative analysis with qualitative methods, such as case studies or interviews, to provide deeper contextual understanding.

Persuasively, quantitative methods are indispensable for comparative politics because they offer objectivity and replicability. Unlike qualitative approaches, which rely on interpretation, statistical analysis provides clear, measurable results that can be verified by other researchers. This transparency is crucial for building cumulative knowledge in the field. For instance, a study showing that countries with proportional representation systems have higher voter turnout can be replicated in different regions or time periods to test its robustness. This iterative process strengthens the credibility of findings and advances the discipline.

In practice, mastering quantitative methods requires both technical skills and critical thinking. Researchers should be proficient in statistical software like R, Stata, or Python, but equally important is the ability to interpret results thoughtfully. For example, a significant p-value does not automatically imply causation—it merely suggests a relationship worth exploring further. Practical tips include starting with descriptive statistics to understand data distribution, using visualization tools like scatterplots to identify trends, and consulting with statisticians when tackling complex models. By combining rigor with creativity, quantitative methods empower comparative politics researchers to answer pressing questions with precision and confidence.

Al Pacino's Political Views: Uncovering the Actor's Stance and Activism

You may want to see also

Comparative Historical Analysis: Analyzes historical events to trace political developments and causal relationships

Comparative Historical Analysis (CHA) is a powerful lens for understanding how past events shape current political landscapes. By examining historical sequences, scholars can identify patterns, uncover causal mechanisms, and challenge assumptions about political development. For instance, consider the rise of welfare states in Europe. CHA reveals how post-World War II reconstruction efforts, combined with the legacy of labor movements, created conditions for expansive social policies. This method doesn’t just describe outcomes; it dissects the *why* and *how* behind them, offering insights that transcend time and geography.

To conduct CHA effectively, researchers must follow a structured process. Begin by selecting a clear research question that links historical events to contemporary political phenomena. Next, identify relevant cases—whether countries, regions, or time periods—that allow for meaningful comparison. For example, comparing the democratization processes in Spain and Chile highlights how differing historical contexts (e.g., Franco’s dictatorship vs. Pinochet’s regime) influenced outcomes. Then, employ process-tracing to map out causal chains, ensuring each link is supported by empirical evidence. Finally, test alternative explanations to strengthen your argument’s robustness.

One of the strengths of CHA is its ability to bridge the gap between macro-level trends and micro-level mechanisms. While large-N studies might show correlations, CHA digs into the *how* behind those relationships. For instance, analyzing the role of colonial legacies in shaping African political institutions requires examining specific historical interactions—such as the imposition of indirect rule in Nigeria versus direct administration in Algeria. This granular approach allows researchers to avoid oversimplification and capture the complexity of political change.

However, CHA is not without challenges. One common pitfall is the risk of selection bias, where cases are chosen to confirm pre-existing theories rather than to explore alternative explanations. To mitigate this, researchers should adopt a transparent case selection process and explicitly discuss potential counterarguments. Additionally, the reliance on historical data means grappling with incomplete or biased sources. Cross-referencing multiple archives and incorporating diverse perspectives can help address this issue.

In practice, CHA is a versatile tool applicable to a wide range of political questions. From understanding the roots of authoritarian resilience in the Middle East to tracing the evolution of gender equality policies in Scandinavia, this method offers a framework for rigorous, context-rich analysis. By grounding contemporary issues in their historical roots, CHA not only deepens our understanding of politics but also equips us to anticipate future developments. For aspiring researchers, mastering this approach requires patience, critical thinking, and a willingness to engage with the past—but the payoff is a richer, more nuanced grasp of the political world.

Navigating Office Politics: Can They Be Avoided or Managed Effectively?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): Employs set-theoretic methods to compare configurations of conditions across cases

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) stands out in comparative politics for its unique approach to identifying complex causal relationships. Unlike traditional methods that seek linear cause-and-effect links, QCA treats conditions as sets and outcomes as intersections or unions of these sets. This set-theoretic logic allows researchers to analyze how combinations of conditions, rather than individual variables, produce specific outcomes. For instance, instead of asking whether democracy is solely determined by economic development, QCA examines how economic development, education levels, and political institutions together configure to produce democratic regimes.

To employ QCA effectively, researchers must follow a structured process. First, define the outcome of interest and identify the potential conditions that might influence it. Second, calibrate these conditions into set memberships, assigning cases to "in" or "out" based on qualitative or quantitative thresholds. For example, a country might be classified as "high GDP per capita" if its GDP exceeds a certain threshold. Third, construct a truth table that maps all possible combinations of conditions and their associated outcomes. Finally, apply Boolean minimization to identify the simplest configurations that consistently explain the outcome. Tools like fsQCA software can assist in this process, ensuring rigor and reproducibility.

One of the strengths of QCA is its ability to handle small-N studies, making it ideal for comparative politics where cases are often limited. However, this method is not without challenges. Researchers must carefully justify their calibration thresholds and ensure that the conditions chosen are theoretically relevant. Missteps in calibration or condition selection can lead to misleading results. Additionally, QCA’s reliance on set-theoretic logic may feel unfamiliar to scholars trained in statistical methods, requiring a shift in mindset. Despite these challenges, QCA offers a powerful framework for uncovering nuanced, context-dependent causal patterns.

A practical example illustrates QCA’s utility. Suppose a researcher investigates why some countries adopt universal healthcare. Traditional regression might highlight GDP as a key factor, but QCA could reveal that high GDP, combined with strong labor unions and a history of social democratic governance, forms a sufficient configuration for universal healthcare adoption. This insight underscores the importance of interplay among conditions, a dimension often lost in variable-centric approaches. By focusing on configurations, QCA provides a richer, more holistic understanding of political phenomena.

In conclusion, QCA is a methodological tool that bridges the gap between qualitative richness and systematic comparison. Its set-theoretic foundation enables researchers to explore how multiple conditions interact to produce outcomes, offering insights that traditional methods might overlook. While it demands careful execution and a departure from conventional analytic habits, QCA’s ability to handle complexity and small-N studies makes it invaluable in comparative politics. For scholars seeking to move beyond linear causality, QCA provides a robust, innovative pathway.

Understanding Partisanship: Political Loyalty, Division, and Its Impact on Democracy

You may want to see also

Most Similar/Most Different Systems Design: Compares similar or dissimilar cases to isolate causal factors

The Most Similar/Most Different Systems Design (MDSD) is a comparative politics methodology that leverages the strategic selection of cases to isolate causal factors. By comparing countries or systems that are either highly similar or highly different, researchers can control for confounding variables and identify the impact of specific factors on political outcomes. For instance, comparing the democratic transitions of Spain and Portugal—two countries with similar cultural, historical, and economic backgrounds—can highlight the role of leadership or institutional design in their successful democratization. Conversely, comparing the political economies of Sweden and Singapore—two countries with vastly different cultural and historical contexts—can reveal how distinct institutional arrangements lead to similar levels of economic development.

To implement MDSD effectively, researchers must first define the dependent variable of interest, such as democratization, economic growth, or policy adoption. Next, they select cases based on their similarity or difference along key independent variables, ensuring that the comparison is theoretically grounded. For example, when studying the impact of federalism on conflict resolution, one might compare India and Nigeria—two federal systems with diverse populations—to isolate the effects of federal institutions on managing ethnic tensions. However, researchers must exercise caution to avoid over-determining the selection of cases, as this can lead to confirmation bias or overlook critical contextual factors.

A practical tip for applying MDSD is to use a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative data with qualitative case studies. Quantitative analysis can help identify patterns across cases, while qualitative analysis provides deeper insights into the mechanisms driving these patterns. For instance, a study on welfare state development might use quantitative data to compare social spending levels in Denmark and the United States, then employ qualitative analysis to explore how historical labor movements shaped these outcomes differently in each country. This dual approach enhances the robustness of findings and allows for a more nuanced understanding of causal relationships.

One of the strengths of MDSD is its ability to balance internal and external validity. By comparing similar cases, researchers can achieve higher internal validity, as the controlled context reduces the influence of extraneous variables. Conversely, comparing different cases enhances external validity by demonstrating the generalizability of findings across diverse settings. For example, a study comparing the environmental policies of Germany and China—two countries with different political systems but similar industrial challenges—can provide insights applicable to both democratic and authoritarian contexts. However, researchers must acknowledge the trade-offs: while MDSD can isolate causal factors, it may also oversimplify complex realities by focusing on a limited number of cases.

In conclusion, the Most Similar/Most Different Systems Design is a powerful tool in comparative politics for isolating causal factors through strategic case selection. By carefully choosing similar or different systems, researchers can control for confounding variables and uncover the mechanisms driving political outcomes. However, successful application requires theoretical rigor, methodological caution, and a mixed-methods approach to balance internal and external validity. When executed thoughtfully, MDSD not only advances scholarly understanding but also informs policy-making by identifying transferable lessons across diverse political contexts.

Are Political Signs Advertising? Exploring the Legal and Ethical Debate

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Comparative politics methodology refers to the systematic approaches and techniques used to study and analyze political systems, institutions, and behaviors across different countries or regions. It involves comparing cases to identify patterns, similarities, and differences.

Comparison is central because it allows scholars to test hypotheses, identify causal relationships, and understand the diversity of political phenomena. By contrasting cases, researchers can isolate variables and draw more robust conclusions.

The main types include the most similar systems design (comparing very similar cases to highlight specific differences), the most different systems design (comparing very different cases to identify common factors), and small-N versus large-N comparisons (studying few or many cases, respectively).

Comparative politics focuses on cross-national or cross-regional analysis, whereas other approaches like American politics or international relations may focus on a single country or global interactions. It emphasizes systematic comparison rather than single-case studies.

Challenges include ensuring comparability across cases, dealing with limited data availability, avoiding selection bias, and balancing between depth and breadth in analysis. Cultural, historical, and contextual differences also complicate comparisons.