Busing in politics refers to the practice of transporting students to schools outside their local neighborhoods, often across racial or socioeconomic lines, as a means to achieve racial integration and address educational inequalities. Emerging prominently in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s as a response to school segregation, busing became a highly contentious political issue, sparking debates over civil rights, local control, and the role of government in education. While proponents argued it was a necessary tool to dismantle systemic racism and provide equal opportunities, opponents criticized it for disrupting communities and imposing undue burdens on families. The policy’s implementation and its aftermath continue to shape discussions on education reform, racial equity, and the limits of federal intervention in local affairs.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Busing refers to the practice of transporting students to schools outside their local neighborhoods, often to achieve racial integration or balance. |

| Historical Context | Originated in the U.S. during the 1950s-1970s as a response to school segregation following the Brown v. Board of Education ruling (1954). |

| Primary Goal | To desegregate schools by redistributing students across racially or socioeconomically diverse areas. |

| Legal Basis | Often mandated by court orders or federal policies to enforce compliance with civil rights laws. |

| Implementation Methods | Students are transported via school buses to schools in different neighborhoods or districts. |

| Controversies | Critics argue it disrupts communities, imposes logistical challenges, and may not address root causes of inequality. |

| Effectiveness | Studies show mixed results; some cases achieved racial diversity, while others faced resistance and limited long-term impact. |

| Current Status | Less common today due to legal changes, but still used in some districts to address racial or socioeconomic imbalances. |

| Key Cases/Policies | Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971) upheld busing as a desegregation tool. |

| Public Opinion | Historically polarizing, with strong opposition from some communities and support from civil rights advocates. |

| Alternatives | Magnet schools, charter schools, and housing policies are sometimes used as alternatives to achieve diversity. |

Explore related products

$17.42 $29.95

$20.5 $22

What You'll Learn

- Origins of Busing: Court-ordered desegregation through student transportation to achieve racial balance in schools

- Legal Basis: Rooted in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and subsequent rulings

- Public Reaction: Sparked protests, white flight, and political backlash in affected communities

- Political Impact: Polarized debates, influenced elections, and shaped education policy nationwide

- Legacy of Busing: Mixed outcomes; reduced segregation but highlighted systemic racial inequalities

Origins of Busing: Court-ordered desegregation through student transportation to achieve racial balance in schools

The roots of busing as a political and social tool trace back to the mid-20th century, when the United States grappled with the legacy of racial segregation in public schools. The landmark 1954 Supreme Court case *Brown v. Board of Education* declared racial segregation in schools unconstitutional, but many districts resisted integration. By the 1960s and 1970s, courts began mandating specific remedies, including the transportation of students across neighborhood lines to achieve racial balance. This practice, known as busing, became a flashpoint in the broader struggle for civil rights, pitting legal mandates against local resistance and sparking debates about equality, community, and education.

Consider the mechanics of court-ordered busing: judges would analyze demographic data to determine the racial composition of schools, then devise transportation plans to redistribute students. For example, in Boston’s 1974 desegregation case, *Morgan v. Hennigan*, federal judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. ordered thousands of students to be bused across the city to integrate predominantly white and Black schools. This approach was not merely logistical; it was a deliberate attempt to dismantle decades of systemic segregation. However, it faced fierce opposition, including protests, violence, and political backlash, highlighting the tension between legal enforcement and societal acceptance.

Analyzing the rationale behind busing reveals its dual purpose: to correct historical injustices and to provide equal educational opportunities. Proponents argued that racially balanced schools would foster cross-cultural understanding and break the cycle of poverty and inequality. Critics, however, contended that busing disrupted communities, imposed undue burdens on families, and failed to address deeper issues like resource disparities between schools. This debate underscores the complexity of using transportation as a tool for social engineering, as it sought to reshape not just schools but the very fabric of society.

A comparative perspective reveals that busing was not unique to the U.S. Similar policies were implemented in other countries, such as Northern Ireland, where integrated education aimed to bridge sectarian divides. Yet, the American experience was distinct due to its roots in racial segregation and the contentious legal battles that defined its implementation. While busing achieved some measure of racial integration, its legacy remains mixed, serving as both a symbol of progress and a reminder of the challenges in translating legal victories into lasting social change.

For those studying or addressing modern educational inequities, the origins of busing offer critical lessons. First, desegregation efforts must be paired with investments in school resources to ensure meaningful equality. Second, community engagement is essential to mitigate resistance and foster buy-in. Finally, while busing was a necessary step in the fight against segregation, it is not a panacea. Today’s policymakers and educators must build on its legacy by addressing systemic issues like housing segregation, funding disparities, and implicit bias, ensuring that the pursuit of racial balance in schools is part of a broader commitment to justice and equity.

Understanding Political Flexibility: Navigating Ideologies and Compromise in Governance

You may want to see also

Legal Basis: Rooted in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and subsequent rulings

The legal foundation of busing in American politics traces its origins to the landmark Supreme Court decision in *Brown v. Board of Education* (1954), which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. This ruling dismantled the "separate but equal" doctrine established by *Plessy v. Ferguson* (1896), setting the stage for desegregation efforts nationwide. However, *Brown* did not provide a mechanism for enforcement, leaving schools largely unchanged for over a decade. It wasn’t until *Brown II* (1955) that the Court ordered desegregation with "all deliberate speed," a vague directive that allowed many districts to resist integration. Busing emerged as a practical solution to achieve racial balance in schools, but its implementation required further legal intervention.

The turning point came in *Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education* (1971), where the Supreme Court explicitly upheld busing as a constitutional tool to remedy segregation. The Court ruled that federal judges could order busing to achieve racial integration, even if it meant transporting students across district lines. This decision empowered courts to take proactive measures, often over local objections, to dismantle racially isolated schools. For example, in Charlotte, North Carolina, busing reduced the percentage of Black students in majority-Black schools from 70% to 19% within a decade. However, the ruling also sparked intense backlash, with critics arguing it infringed on local control and parental choice.

Subsequent rulings refined the scope and limitations of busing. In *Milliken v. Bradley* (1974), the Court restricted busing to within individual districts, preventing cross-district plans unless segregation was proven to be interdistrict in nature. This decision effectively limited the reach of busing in metropolitan areas, where residential segregation often mirrored school segregation. Meanwhile, *Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1* (2007) further constrained busing by striking down voluntary integration plans that used race as a primary factor in student assignments. These rulings reflect the evolving legal landscape, where busing remains a contentious tool for achieving racial equity in education.

Despite its legal basis, busing’s effectiveness and fairness have been hotly debated. Proponents argue it is a necessary measure to counteract decades of systemic segregation, while opponents criticize it for disrupting communities and imposing logistical burdens. Practical implementation requires careful planning, such as minimizing travel time for students, ensuring safety, and addressing parental concerns. For instance, successful busing programs in cities like Boston and Louisville paired transportation with investments in school resources and community engagement. Ultimately, the legal framework rooted in *Brown* provides the authority for busing, but its success depends on thoughtful execution and broader societal commitment to equity.

Navigating Identity Politics: Strategies for Building Inclusive Academy Spaces

You may want to see also

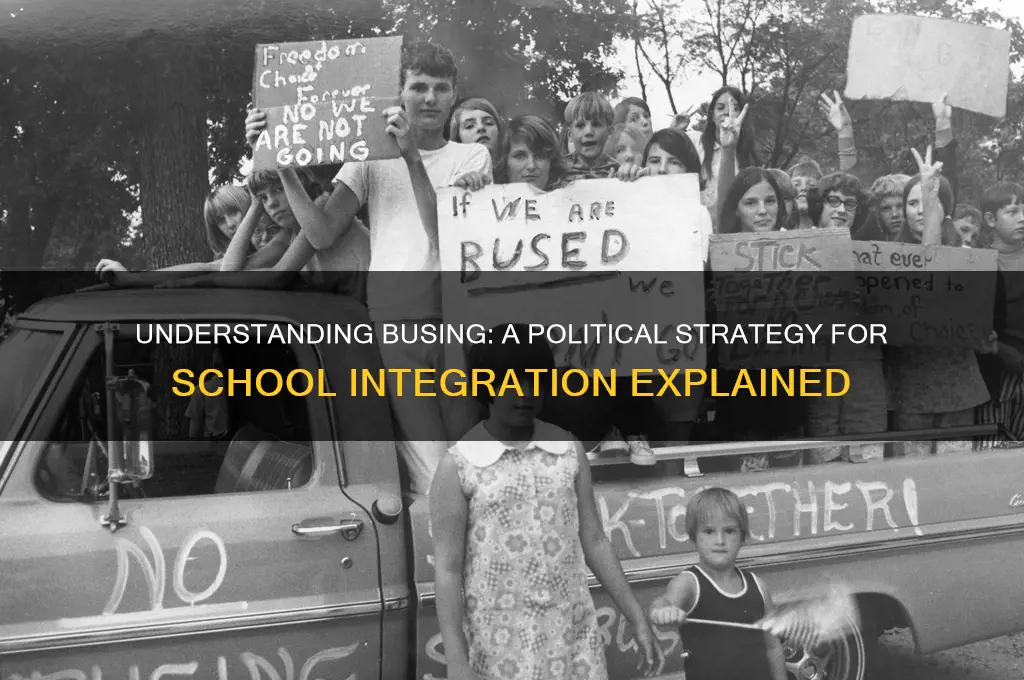

Public Reaction: Sparked protests, white flight, and political backlash in affected communities

The implementation of busing as a tool for school desegregation in the 1960s and 1970s ignited a firestorm of public reaction, revealing deep-seated racial tensions and resistance to change. In Boston, for example, the 1974 court-ordered busing plan to integrate schools led to violent protests, with white residents hurling racial slurs and projectiles at Black students. These scenes were not isolated; similar outbreaks occurred in cities like Detroit and Los Angeles, where the forced mixing of student populations became a flashpoint for racial animosity. The visceral opposition underscored the challenges of translating legal mandates into societal acceptance.

One of the most significant consequences of busing was the phenomenon known as "white flight," where white families relocated to suburban areas to avoid integrated schools. In cities like Milwaukee, enrollment in public schools plummeted as white students were transferred to predominantly Black schools. This exodus not only undermined the goal of desegregation but also exacerbated racial and economic disparities, as suburban schools became increasingly homogeneous and well-funded, while urban schools struggled with dwindling resources. The unintended consequence was a de facto resegregation that persists to this day.

Political backlash against busing was swift and fierce, reshaping the American political landscape. In Boston, anti-busing sentiment fueled the rise of politicians like Louise Day Hicks, who capitalized on white resentment to gain political power. Nationally, the issue became a rallying cry for conservatives, contributing to the realignment of the Republican Party around themes of states' rights and local control. The 1972 presidential campaign saw Richard Nixon exploit anti-busing sentiment, framing it as an example of judicial overreach, a strategy that resonated with white voters and solidified opposition to federal intervention in local education.

Despite its contentious legacy, busing remains a critical case study in the complexities of social engineering. Proponents argue that it exposed the stark inequalities in education and forced a national conversation on race. Critics, however, point to its polarizing effects and limited long-term success in achieving true integration. For communities grappling with similar issues today, the busing era offers a cautionary tale: meaningful change requires not just legal mandates but also grassroots efforts to address systemic racism and build trust across racial divides. Practical steps, such as fostering diverse school leadership and investing in culturally responsive curricula, can help mitigate the backlash that doomed earlier efforts.

Black Panther: A Politically Charged Marvel Masterpiece or Mere Fiction?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political Impact: Polarized debates, influenced elections, and shaped education policy nationwide

Busing, the practice of transporting students to schools outside their neighborhoods to achieve racial integration, ignited some of the most polarized debates in American political history. In the 1970s, court-ordered busing mandates became a lightning rod for racial tensions, pitting communities against one another. Proponents argued it was a necessary tool to dismantle segregation and provide equal educational opportunities, while opponents decried it as an overreach of federal power and a disruption to local communities. This divide wasn’t just ideological; it was deeply personal, with parents on both sides fearing for their children’s safety, cultural identity, and educational quality. The result? A nation fractured along racial, economic, and political lines, with busing becoming a symbol of both progress and resistance.

Consider the 1974 Boston desegregation crisis, where busing orders led to violent protests, school boycotts, and a city on the brink of racial war. This wasn’t an isolated incident. Across the country, from Los Angeles to Charlotte, busing sparked similar conflicts, often fueled by misinformation and fear. Yet, these debates weren’t merely local—they influenced national elections, with politicians leveraging the issue to rally their bases. Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” and Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign both capitalized on anti-busing sentiment, framing it as a fight against government intrusion. Conversely, Democrats struggled to balance their commitment to civil rights with the backlash from white working-class voters. Busing, thus, became a political football, shaping electoral strategies and party identities for decades.

The impact of busing on education policy cannot be overstated. It forced a national reckoning with the legacy of segregation, pushing policymakers to address inequities in funding, resources, and opportunities. While busing itself has largely been phased out, its legacy lives on in magnet schools, charter schools, and diversity initiatives designed to achieve integration without forced transportation. However, these alternatives have their own limitations, often failing to address the root causes of educational inequality. Busing’s lesson is clear: integration is not just about moving students; it’s about transforming systems. Yet, the political backlash it provoked has made policymakers wary of bold, systemic reforms, leaving many schools as segregated today as they were in the 1960s.

To understand busing’s enduring political impact, look no further than the 2020 debates over critical race theory and “wokeness” in education. The same fault lines—race, class, and federal authority—continue to shape discussions about equity in schools. Busing taught us that integration is not a neutral policy; it challenges power structures and forces uncomfortable conversations. For educators and policymakers, the takeaway is this: any effort to address inequality must anticipate and navigate political resistance. Practical steps include engaging communities early, framing integration as a shared benefit, and pairing busing-like initiatives with broader investments in underserved schools. Without this, even well-intentioned policies risk becoming political battlegrounds rather than tools for change.

Ultimately, busing’s political legacy is a cautionary tale about the intersection of race, education, and power. It demonstrates how a single policy can polarize a nation, influence elections, and shape the trajectory of education reform. Yet, it also highlights the enduring need for bold action to address systemic inequities. As we grapple with today’s education challenges, from school funding to diversity, busing reminds us that progress requires not just policy innovation but political courage. The question remains: are we willing to learn from history, or will we repeat its mistakes?

Is Academic Sociology Politically Obsolete? A Critical Reevaluation

You may want to see also

Legacy of Busing: Mixed outcomes; reduced segregation but highlighted systemic racial inequalities

Busing, a policy aimed at desegregating schools by transporting students to different districts, emerged as a contentious tool in the fight against racial segregation. Its legacy is a complex tapestry of progress and unintended consequences. While it undeniably chipped away at the physical barriers of segregation, its impact on systemic racial inequalities remains a subject of debate.

Busing's most tangible success lies in its ability to physically integrate schools. In cities like Boston and Charlotte, busing led to a measurable increase in racial diversity within classrooms. This exposure to different backgrounds fostered cross-racial understanding and challenged stereotypes, benefiting both minority and majority students. Studies have shown that integrated learning environments can lead to improved academic outcomes for all students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

However, busing's effectiveness in addressing systemic inequalities was limited. It often faced fierce resistance, highlighting the deep-seated racial tensions it sought to overcome. White flight, where white families moved to suburbs to avoid integrated schools, undermined the policy's goals. This phenomenon perpetuated de facto segregation, as affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods maintained their homogeneity. Furthermore, busing did little to address the root causes of educational disparities, such as unequal funding, biased curricula, and discriminatory practices within schools themselves.

Busing served as a catalyst, exposing the entrenched nature of racial inequality in education. It demonstrated that simply moving students around wasn't enough to dismantle systemic barriers. The policy's mixed legacy underscores the need for a multi-pronged approach that tackles segregation at its source. This includes equitable funding formulas, diverse teacher recruitment, culturally responsive curricula, and community engagement initiatives.

The legacy of busing reminds us that true desegregation requires more than just physical integration. It demands a commitment to addressing the underlying structures that perpetuate racial disparities in education. While busing played a crucial role in breaking down physical barriers, its ultimate success lies in inspiring a broader movement towards educational equity.

How Fixed Political Machines Shaped Modern Governance and Power Structures

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Busing in politics refers to the practice of transporting students to schools outside their local neighborhoods, often to achieve racial integration or address educational inequalities.

Busing was implemented primarily to desegregate schools following the 1954 Supreme Court decision in *Brown v. Board of Education*, which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional.

The main goals of busing include promoting racial integration, ensuring equal educational opportunities, and addressing disparities in resources between predominantly minority and white schools.

Busing has been controversial due to concerns about forced relocation, loss of neighborhood schools, increased transportation costs, and resistance from communities opposed to integration.

While large-scale busing programs have declined since the 1970s and 1980s, some districts still use busing as a tool for desegregation or to provide access to specialized educational programs.