Fixed political machines, often rooted in urban areas, were powerful organizations that dominated local and sometimes state politics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These machines were characterized by their ability to control elections, distribute patronage, and maintain influence through a network of loyal supporters and corrupt practices. They thrived by providing services to immigrants and marginalized communities in exchange for political loyalty, effectively consolidating power through a system of quid pro quo. However, their dominance was eventually challenged by progressive reforms, legal crackdowns, and shifting public attitudes toward corruption, leading to their decline but leaving a lasting impact on American political history.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A fixed political machine is a well-organized, hierarchical system of political power that controls resources, patronage, and influence to maintain dominance in a specific geographic area. |

| Key Features | - Strong centralized leadership - Control over local government and institutions - Use of patronage (jobs, favors) to secure loyalty - Manipulation of elections and voter turnout - Long-term dominance in a specific region |

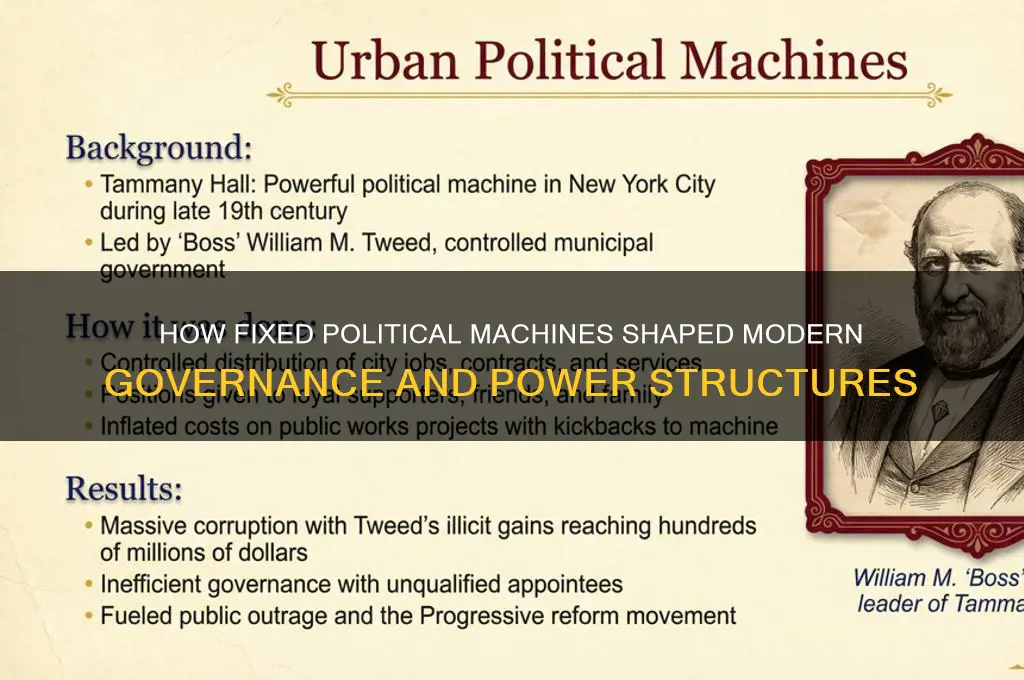

| Historical Examples | Tammany Hall (New York City, 19th-20th century) Daley Machine (Chicago, mid-20th century) Modern examples in some developing countries or regions with weak governance |

| Methods of Control | - Control of local police, courts, and public services - Intimidation and coercion of opponents - Fraudulent voting practices - Distribution of resources to loyal supporters |

| Impact on Democracy | Undermines fair elections, reduces political competition, and limits citizen participation in governance. |

| Modern Adaptations | Use of technology for voter targeting, social media manipulation, and data-driven campaigns to maintain control. |

| Countermeasures | Electoral reforms, anti-corruption laws, increased transparency, and civic engagement to dismantle machine influence. |

Explore related products

$20.98 $39

What You'll Learn

- Boss-led hierarchies: Strong leaders controlled patronage networks, ensuring loyalty and influence over local politics

- Patronage systems: Jobs and favors were exchanged for political support, solidifying machine power

- Voter control: Machines used tactics like voter fraud and intimidation to manipulate election outcomes

- Urban dominance: Machines thrived in cities, leveraging dense populations for political and economic control

- Reform movements: Progressive Era efforts exposed corruption, leading to laws dismantling machine structures

Boss-led hierarchies: Strong leaders controlled patronage networks, ensuring loyalty and influence over local politics

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, boss-led hierarchies were the backbone of many urban political machines. These systems thrived on the charisma, cunning, and organizational prowess of strong leaders who wielded power through patronage networks. Figures like Boss Tweed in New York City and Mayor Richard J. Daley in Chicago exemplified this model, using their control over jobs, contracts, and favors to cement loyalty and dominate local politics. Their ability to deliver tangible benefits—such as employment, housing, or infrastructure improvements—made them indispensable to their communities, even as critics decried corruption and cronyism.

Consider the mechanics of these networks: a boss at the top distributed resources to lieutenants, who in turn mobilized precinct captains and ward heelers. This pyramid structure ensured that every layer of the hierarchy had a stake in the system’s survival. For instance, a precinct captain might secure a city job for a constituent in exchange for votes or campaign support. This transactional relationship fostered deep-rooted loyalty, as followers depended on the boss for their livelihoods and influence. The system’s efficiency lay in its ability to bypass bureaucratic red tape, delivering results quickly and directly—a stark contrast to the often slow-moving machinery of formal government.

However, the strength of boss-led hierarchies also contained the seeds of their downfall. The concentration of power in a single individual made the system vulnerable to scandals, legal crackdowns, or the boss’s eventual demise. When Boss Tweed’s Tammany Hall machine collapsed under the weight of corruption charges, it exposed the fragility of a model reliant on one person’s charisma and connections. Similarly, the death or retirement of a long-serving boss often left a power vacuum, as successors struggled to replicate the same level of control and loyalty. This highlights a critical caution: while boss-led hierarchies can be effective in the short term, their sustainability depends on institutionalizing power rather than personalizing it.

To understand the legacy of these systems, examine their impact on modern politics. While overt political machines have largely faded, their tactics persist in the form of campaign financing, voter mobilization, and strategic resource allocation. Contemporary leaders who build strong, centralized networks—whether in local government or national politics—often draw from the playbook of boss-led hierarchies. For instance, the ability to reward supporters with appointments or favors remains a powerful tool for maintaining influence. The takeaway? While the era of the political boss may be over, the principles of loyalty, patronage, and hierarchical control continue to shape political landscapes today.

Does CNN Have Political Bias? Analyzing Media Slant and Objectivity

You may want to see also

Patronage systems: Jobs and favors were exchanged for political support, solidifying machine power

Patronage systems were the lifeblood of political machines, transforming them from fragile coalitions into entrenched power structures. At their core, these systems operated on a simple yet effective principle: jobs and favors in exchange for unwavering political loyalty. This quid pro quo dynamic created a network of dependency, where citizens relied on the machine for employment or assistance, and the machine, in turn, relied on these citizens to deliver votes, mobilize communities, and maintain its dominance.

Consider the Tammany Hall machine in 19th-century New York City. Immigrants, often marginalized and struggling to find work, were offered jobs as street cleaners, clerks, or even police officers in exchange for their support at the ballot box. This not only secured votes but also fostered a sense of gratitude and obligation, making it difficult for challengers to break the machine's hold.

The effectiveness of patronage systems lay in their ability to address immediate needs while simultaneously building long-term political capital. By providing jobs, machines alleviated poverty and gained the loyalty of entire families and communities. Favors, ranging from legal assistance to access to social services, further solidified this bond. This system was particularly potent in urban areas, where poverty and inequality were rampant, and where the machine could position itself as a provider and protector.

However, the very strength of patronage systems also sowed the seeds of their eventual decline. The blatant exchange of jobs for votes became increasingly scrutinized as democratic ideals evolved. Public outrage over corruption and inefficiency, coupled with civil service reforms aimed at merit-based hiring, gradually dismantled the patronage networks that had sustained political machines for decades.

Understanding the mechanics of patronage systems offers valuable insights into the rise and fall of political machines. While they provided a means of survival for many, they ultimately undermined the principles of fair governance and equal opportunity. The legacy of these systems serves as a cautionary tale, reminding us of the dangers of prioritizing political power over the public good.

Evolving Politoed in Scarlet: A Step-by-Step Guide for Trainers

You may want to see also

Voter control: Machines used tactics like voter fraud and intimidation to manipulate election outcomes

Political machines have long relied on voter control as a cornerstone of their power, employing tactics that range from subtle manipulation to outright coercion. One of the most notorious methods was voter fraud, which took many forms. For instance, machines often stuffed ballot boxes with fake votes or allowed individuals to vote multiple times under different names. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Tammany Hall in New York City was infamous for such practices, ensuring their candidates’ victories through manufactured majorities. This systemic fraud undermined the integrity of elections, turning democratic processes into mere formalities controlled by machine bosses.

Intimidation was another tool in the machine’s arsenal, often targeting vulnerable populations to suppress opposition. Strong-arm tactics, such as physical threats or economic coercion, were used to deter voters from supporting rival candidates. For example, in Chicago during the 1920s, Al Capone’s gang worked with political machines to ensure favorable election outcomes, using violence to silence dissent. Similarly, machines would threaten immigrants with deportation or loss of jobs if they failed to vote as instructed. These methods created an atmosphere of fear, effectively neutralizing opposition and consolidating machine control over electoral outcomes.

A more insidious form of voter control involved manipulating voter rolls and registration processes. Machines would purge lists of opponents’ supporters or add fictitious names to inflate their voter base. In some cases, they controlled polling places directly, stationing loyalists as election officials who could challenge or reject ballots at will. This administrative control allowed machines to skew results before a single vote was cast, ensuring their candidates’ victories without resorting to overt violence. Such tactics highlight the machines’ ability to exploit systemic weaknesses for their gain.

Despite their effectiveness, these methods were not without risk. Public outrage and legal reforms eventually began to dismantle the machines’ grip on voter control. The introduction of secret ballots, for instance, reduced the machines’ ability to monitor and coerce individual votes. Similarly, federal legislation like the Voting Rights Act of 1965 targeted intimidation and fraud, empowering voters and weakening machine dominance. While remnants of these tactics persist in modern politics, understanding their historical use offers valuable lessons in safeguarding democratic processes against manipulation.

Understanding Political Depression: Causes, Symptoms, and Societal Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Urban dominance: Machines thrived in cities, leveraging dense populations for political and economic control

Political machines found fertile ground in urban centers, where dense populations provided the raw material for their power. Cities offered a concentrated pool of voters, workers, and resources, allowing machine bosses to establish networks of control that permeated every level of society. This urban dominance was not merely a byproduct of geography but a strategic choice, as machines exploited the unique dynamics of city life to solidify their grip on political and economic systems.

Consider the mechanics of this control. In cities like New York and Chicago during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, machines like Tammany Hall and the Daley machine thrived by offering services in exchange for loyalty. They provided jobs, housing, and even food to immigrants and the working class, who were often overlooked by mainstream institutions. This quid pro quo system ensured a steady stream of votes and created a dependency cycle that reinforced machine power. For instance, Tammany Hall’s control over patronage jobs in New York City’s public works projects gave them unparalleled influence over the city’s labor force, effectively turning workers into political foot soldiers.

However, this dominance was not without its vulnerabilities. The very density that enabled machine control also created challenges. Urban populations were diverse, with competing interests and ideologies, making it difficult to maintain monolithic control. Machines had to constantly adapt, balancing the demands of different ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic groups. For example, in Chicago, the Daley machine had to navigate the tensions between African American communities seeking civil rights and white ethnic groups resistant to change. This required a delicate mix of coercion, compromise, and co-optation, showcasing the complexity of maintaining urban dominance.

To replicate or counter such systems today, one must understand the interplay between population density and resource distribution. Modern urban planners and policymakers can learn from these historical examples by focusing on equitable resource allocation to prevent the concentration of power. For instance, decentralizing public services and fostering community-led initiatives can dilute the influence of any single entity. Conversely, organizations seeking to build influence in cities should prioritize grassroots engagement, offering tangible benefits that address the specific needs of diverse urban populations.

Ultimately, the urban dominance of political machines highlights the dual-edged nature of city life: its potential for both empowerment and exploitation. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into how dense populations can be mobilized for control—and how they can be empowered to resist it. The lessons are clear: in cities, power is not just taken; it is built, brick by brick, through the strategic use of resources and relationships.

Unveiling the Mystery: Understanding the Political Group Q Phenomenon

You may want to see also

Reform movements: Progressive Era efforts exposed corruption, leading to laws dismantling machine structures

The Progressive Era, spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries, marked a pivotal moment in American history when reform movements systematically exposed and dismantled the corrupt political machines that had long dominated urban governance. These machines, often controlled by powerful bosses, thrived on patronage, voter fraud, and kickbacks, effectively hijacking democratic processes for personal gain. Reformers, armed with investigative journalism and grassroots activism, shone a light on these abuses, galvanizing public outrage and legislative action. The era’s hallmark was the passage of laws like the Civil Service Reform Act of 1883, which replaced patronage-based hiring with merit-based systems, and the direct primary system, which shifted candidate selection from party bosses to voters. These reforms not only weakened machine structures but also restored public trust in government institutions.

Consider the case of New York City’s Tammany Hall, a notorious political machine that controlled the city’s politics for decades. Investigative journalists like Lincoln Steffens exposed Tammany’s corruption in his 1903 work *The Shame of the Cities*, detailing how bosses like George Washington Plunkitt exploited public resources for private profit. Steffens’ exposés, coupled with the efforts of reformers like Theodore Roosevelt, led to the election of Mayor Seth Low in 1901, who implemented civil service reforms and reduced Tammany’s influence. This example illustrates how targeted exposés and political will could dismantle even the most entrenched machines. Practical tip: When studying reform movements, focus on the interplay between media, public opinion, and legislative action to understand how systemic change occurs.

Analytically, the Progressive Era’s success in dismantling political machines rested on three key strategies: transparency, accountability, and decentralization. Transparency was achieved through muckraking journalism, which uncovered corruption and made it impossible for machines to operate in the shadows. Accountability was enforced via laws like the Seventeenth Amendment (1913), which mandated the direct election of senators, stripping machines of their control over state legislatures. Decentralization shifted power from party bosses to citizens through initiatives like the secret ballot and recall elections. These strategies, when combined, created a framework that not only dismantled existing machines but also prevented their resurgence.

Persuasively, the lessons of the Progressive Era remain relevant today. Modern political machines, though less overt, still exploit systemic vulnerabilities—gerrymandering, dark money, and voter suppression—to maintain power. Reformers can draw inspiration from the Progressive Era by prioritizing transparency initiatives, such as campaign finance disclosure laws, and accountability measures, like independent redistricting commissions. Additionally, leveraging technology to engage citizens directly, as reformers did with direct primaries, can decentralize power and reduce machine influence. Takeaway: The fight against political corruption is ongoing, but the Progressive Era proves that with strategic reforms and public mobilization, even the most entrenched systems can be transformed.

Descriptively, the Progressive Era’s reform movements were a tapestry of diverse efforts, from women’s suffrage to antitrust legislation, all united by a commitment to fairness and accountability. In cities like Chicago and St. Louis, reformers established nonpartisan leagues to monitor elections and expose fraud. In statehouses, they pushed for laws limiting corporate donations to political parties. These efforts, though fragmented, collectively created a momentum that forced politicians to act. Practical tip: When advocating for reform, build coalitions across issues—environmentalists, labor activists, and good governance groups can unite under the banner of transparency and accountability to amplify their impact. The Progressive Era’s legacy is a reminder that systemic change requires both targeted action and broad collaboration.

Are Political Contributions Taxable in Florida? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A fixed political machine is a well-organized, often corrupt political organization that maintains control over a city, region, or government through patronage, voter manipulation, and sometimes illegal activities.

Fixed political machines gained power by offering jobs, services, and favors in exchange for political support, controlling elections through voter fraud, and building strong networks of loyal followers.

Bosses were the leaders of fixed political machines who made key decisions, distributed patronage, and ensured the machine’s dominance by managing resources and alliances.

The decline of fixed political machines was driven by reforms such as the introduction of civil service systems, anti-corruption laws, and increased public scrutiny of political practices.

While traditional fixed political machines have largely disappeared, elements of machine politics, such as patronage and voter mobilization, still exist in some forms in modern political systems.