Brownshirt politics refers to the ideology and practices associated with the Sturmabteilung (SA), the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party in Germany during the 1920s and 1930s. Named for their distinctive brown uniforms, the SA played a crucial role in Adolf Hitler’s rise to power by employing violence, intimidation, and street-level aggression to suppress political opponents, particularly communists and socialists. Their tactics included breaking up meetings, attacking dissenters, and fostering a climate of fear to consolidate Nazi control. Beyond their role as enforcers, the Brownshirts embodied the extremist nationalism, racism, and authoritarianism central to Nazi ideology. Their legacy serves as a stark symbol of the dangers of political extremism, the erosion of democratic institutions, and the use of violence to achieve ideological dominance. Today, the term brownshirt politics is often invoked to describe modern movements or groups that employ similar tactics of intimidation and authoritarianism to advance their agendas.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins of Brownshirts: Early 20th-century paramilitary group linked to Nazi Party in Germany

- Role in Nazi Rise: Intimidation tactics, street violence, and suppression of political opponents

- Ideology and Uniform: Nationalistic, anti-communist, and fascist beliefs; brown shirts as iconic symbol

- Leadership and Structure: Led by Ernst Röhm; organized under SA (Sturmabteilung) hierarchy

- Decline and Legacy: Dissolved after Night of Long Knives; influenced modern extremist movements

Origins of Brownshirts: Early 20th-century paramilitary group linked to Nazi Party in Germany

The Brownshirts, formally known as the Sturmabteilung (SA), emerged in the chaotic aftermath of World War I, a period marked by political instability, economic hardship, and widespread disillusionment in Germany. Founded in 1921 by Ernst Röhm, the SA initially served as a protective force for Nazi Party meetings, which were frequently disrupted by rival political groups. Their name derived from the khaki-brown uniforms they wore, a practical choice influenced by surplus military stock from the war. This paramilitary group quickly became a symbol of aggression and intimidation, embodying the violent ethos of early Nazism.

The SA’s rise was fueled by the Weimar Republic’s fragility and the appeal of radical nationalism among disaffected veterans, workers, and youth. Unlike traditional military units, the Brownshirts operated as a loosely organized street militia, prioritizing brute force over discipline. Their tactics included physical assaults on political opponents, particularly communists and socialists, and the disruption of public gatherings. This violence was not random but strategically aimed at consolidating Nazi influence and suppressing dissent. By the mid-1920s, the SA had grown into a formidable force, numbering in the tens of thousands, and became a key instrument in Adolf Hitler’s ascent to power.

A critical turning point for the Brownshirts came during the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, a failed coup attempt led by Hitler. Although the SA’s role was limited, the event cemented their loyalty to Hitler and their willingness to engage in extreme measures for the Nazi cause. Following Hitler’s imprisonment and the temporary ban on the Nazi Party, the SA continued to operate underground, maintaining its structure and recruiting new members. This resilience highlighted their importance as a grassroots enforcer of Nazi ideology, bridging the gap between political rhetoric and street-level action.

Despite their early contributions, the SA’s influence waned after the Nazis seized power in 1933. Hitler, now chancellor, viewed the Brownshirts’ independence and radicalism as a threat to his consolidation of control. The Night of the Long Knives in 1934 marked the brutal purge of SA leadership, including Röhm, effectively subordinating the group to the SS. This event underscored the SA’s role as a disposable tool in the Nazis’ rise to power, discarded once its utility diminished. Yet, their legacy as the violent vanguard of Nazi ideology remains a stark reminder of how paramilitary groups can exploit societal unrest to advance extremist agendas.

Understanding the origins of the Brownshirts offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked paramilitary organizations in times of political turmoil. Their story illustrates how economic despair, nationalist fervor, and charismatic leadership can converge to create a force capable of destabilizing democracies. While the SA’s specific context is rooted in early 20th-century Germany, their tactics and trajectory hold lessons for contemporary societies grappling with the rise of extremist groups. Vigilance against the normalization of political violence and the erosion of democratic norms remains essential to prevent history from repeating itself.

Understanding Political Standpoints: Defining Core Beliefs and Their Impact

You may want to see also

Role in Nazi Rise: Intimidation tactics, street violence, and suppression of political opponents

The Brownshirts, officially known as the Sturmabteilung (SA), were the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, and their role in the rise of Nazism was characterized by a relentless campaign of intimidation, street violence, and suppression of political opponents. These tactics were not merely incidental but central to the Nazi strategy of seizing power. By creating an atmosphere of fear and chaos, the SA undermined democratic institutions and paved the way for Hitler’s authoritarian regime. Their methods were calculated, brutal, and effective, serving as a blueprint for modern political extremism.

Consider the SA’s use of intimidation tactics, which were designed to silence dissent and assert Nazi dominance in public spaces. Brownshirts would disrupt political rallies of opposing parties, often using physical force to break up meetings or prevent speakers from being heard. For instance, during the early 1930s, the SA targeted Social Democratic and Communist gatherings, employing tactics like throwing stink bombs, shouting down speakers, and engaging in brawls. These actions were not random acts of violence but part of a coordinated effort to demoralize opponents and demonstrate Nazi strength. The message was clear: resist, and face the consequences.

Street violence was another cornerstone of the SA’s strategy, serving both as a tool of terror and a means of recruitment. Brownshirts patrolled neighborhoods, particularly in working-class areas, where they clashed with rival political groups and enforced Nazi ideology through brute force. The infamous “Battle of the Bismarck School” in 1930, where SA members violently confronted police, exemplified their willingness to challenge state authority. This violence was not just about control; it was a spectacle designed to attract disaffected youth and veterans, offering them a sense of purpose and camaraderie in a post-World War I society marked by economic hardship and political instability.

Suppression of political opponents went beyond physical violence to include systemic harassment and exclusion. The SA targeted not only rival politicians but also journalists, intellectuals, and anyone deemed a threat to Nazi ideology. They boycotted Jewish businesses, vandalized property, and compiled lists of “enemies of the state.” This campaign of suppression was instrumental in dismantling the Weimar Republic’s fragile democracy. By 1933, when Hitler became chancellor, the SA’s efforts had significantly weakened opposition parties, making it easier for the Nazis to consolidate power and eliminate dissent through legal and extralegal means.

The SA’s role in the Nazi rise offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked political violence. Their tactics—intimidation, street violence, and suppression—were not anomalies but deliberate strategies to destabilize democracy and impose authoritarian rule. Understanding this history is crucial for recognizing and countering similar patterns in contemporary politics. Vigilance against such methods is not just a historical lesson but a practical necessity for safeguarding democratic values today.

Understanding the Role of a Political Gadfly in Modern Society

You may want to see also

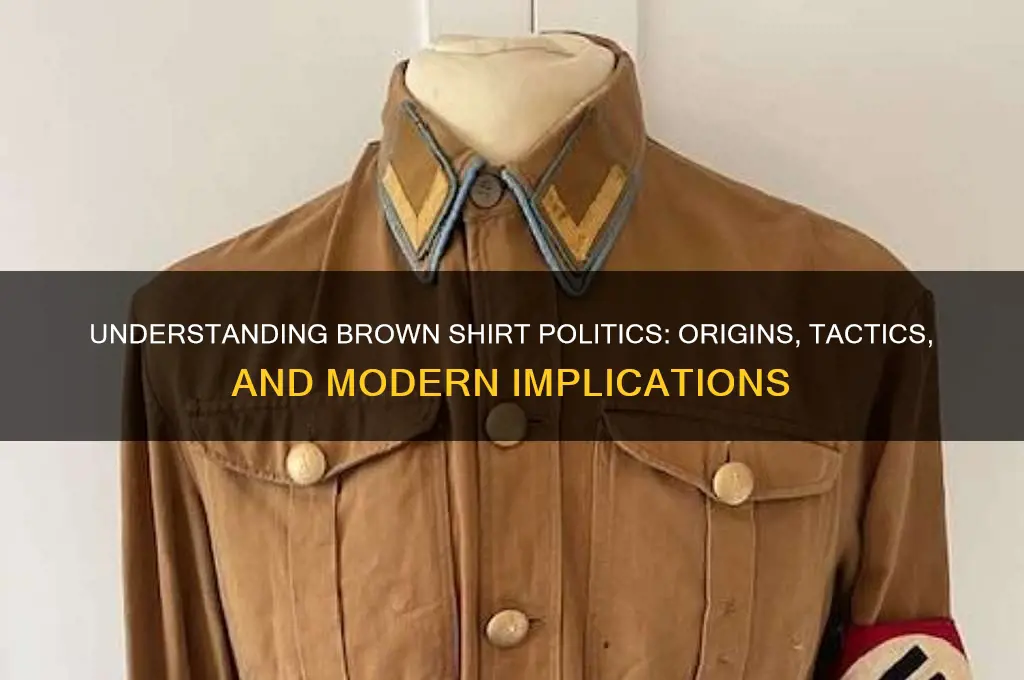

Ideology and Uniform: Nationalistic, anti-communist, and fascist beliefs; brown shirts as iconic symbol

The brown shirt, a simple garment, became a powerful symbol of a dangerous ideology. This uniform, adopted by the Nazi Party’s paramilitary wing, the Sturmabteilung (SA), represented a toxic blend of nationalism, anti-communism, and fascism. Worn by thugs and ideologues alike, it signaled a rejection of democratic values and a commitment to violent revolution. The brown shirt was more than cloth—it was a visual manifesto, instantly recognizable and deeply feared.

To understand the brown shirt’s significance, consider its role in fascist propaganda. The uniform standardized appearance, fostering a sense of unity and discipline among members. This uniformity also dehumanized the individual, reducing wearers to cogs in a larger machine. Pairing the brown shirt with nationalist rhetoric and anti-communist hysteria created a potent identity for disaffected Germans. It promised purpose, belonging, and a scapegoat for societal woes. Practical tip: When analyzing historical symbols, examine how they were used to manipulate emotions and consolidate power.

Compare the brown shirt to other political uniforms, such as the red shirts of Italian fascists or the black shirts of Mussolini’s followers. Each color carried specific connotations, but all served the same purpose: to visibly demarcate the in-group from outsiders. The brown shirt, however, stood out for its association with street violence and intimidation. SA members used their uniforms to provoke fear, breaking up political meetings and attacking opponents. This tactic, known as *Gleichschaltung*, aimed to silence dissent and enforce ideological conformity. Caution: Do not underestimate the psychological impact of uniforms in political movements—they can normalize extremism.

The brown shirt’s legacy endures as a cautionary tale. Its iconic status reminds us how clothing can be weaponized to advance hateful ideologies. Today, neo-fascist groups often adopt similar uniforms or symbols to evoke historical precedents. To counter this, educate yourself and others about the origins and dangers of such iconography. Practical step: Engage in discussions about the role of symbolism in politics, using the brown shirt as a case study.

In conclusion, the brown shirt was not merely a uniform but a tool of fascist ideology. Its design and deployment illustrate how nationalism, anti-communism, and authoritarianism can be packaged into a single, striking image. By studying its history, we gain insight into the mechanics of extremism and the importance of resisting its resurgence. Takeaway: Symbols matter—they shape identities, justify violence, and perpetuate division. Recognize them, understand them, and challenge their misuse.

How Political Affiliations Shaped Our Personal Identities and Divided Us

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Leadership and Structure: Led by Ernst Röhm; organized under SA (Sturmabteilung) hierarchy

Ernst Röhm, a hardened World War I veteran, was the architect of the Sturmabteilung (SA), the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. His leadership transformed the SA into a formidable force, blending military discipline with street-level brutality. Röhm’s vision was clear: to create a loyal, aggressive cadre that would enforce Nazi ideology through intimidation and violence. Under his command, the SA hierarchy became a mirror of his own uncompromising nature—structured, hierarchical, and ruthlessly efficient. This organization was not merely a political tool but a cult of personality, with Röhm at its center, shaping its tactics and ideology.

The SA’s structure was designed to maximize control and mobility. Divided into regional groups, known as *Standarten*, each unit operated with autonomy but remained firmly under Röhm’s command. This decentralized yet unified model allowed the SA to adapt quickly to local conditions while maintaining a cohesive strategy. Members were trained in paramilitary tactics, from hand-to-hand combat to crowd control, ensuring they could both inspire fear and maintain order. Röhm’s emphasis on physical prowess and loyalty created a culture of camaraderie and fanaticism, making the SA a potent instrument of Nazi power.

Röhm’s leadership, however, was not without tension. His radical views often clashed with those of Adolf Hitler, particularly regarding the SA’s role in the Nazi regime. While Hitler saw the SA as a means to seize power, Röhm envisioned it as the core of a socialist revolution. This ideological rift ultimately led to Röhm’s downfall during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934, when Hitler purged the SA leadership to consolidate his authority. Despite his demise, Röhm’s imprint on the SA’s structure and ethos remained, shaping its legacy as a symbol of brown shirt politics.

To understand the SA’s impact, consider its role in the Nazi rise to power. The organization’s hierarchical structure allowed for rapid mobilization during political campaigns, while its violent tactics silenced opposition and intimidated voters. For instance, during the 1932 elections, SA units disrupted rallies of rival parties, ensuring Nazi dominance at the polls. This blend of military organization and political aggression exemplifies the essence of brown shirt politics—a fusion of leadership, structure, and force to achieve ideological goals.

In practical terms, the SA’s model offers a cautionary tale for modern political movements. While hierarchical organization can provide efficiency and unity, it also risks becoming a tool for authoritarianism. Leaders like Röhm, who prioritize loyalty over dissent, create environments ripe for abuse. For those studying political structures, the SA’s history underscores the importance of checks and balances, even within seemingly cohesive organizations. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for recognizing—and resisting—the resurgence of brown shirt tactics in contemporary politics.

Are English Classes Politically Biased? Exploring Literature's Ideological Influence

You may want to see also

Decline and Legacy: Dissolved after Night of Long Knives; influenced modern extremist movements

The Night of the Long Knives marked the abrupt end of the Brownshirts' reign, a brutal purge orchestrated by Hitler to consolidate power. On June 30, 1934, SS and Gestapo forces executed Ernst Röhm, the SA leader, along with approximately 85 to 200 other perceived rivals. This event dismantled the Brownshirts' influence, reducing them from a formidable paramilitary force of over 3 million members to a ceremonial role. The purge was justified as a necessary measure to restore order, but it was, in reality, a calculated move to eliminate a potential threat to Hitler’s authority. This dissolution highlights the volatile nature of extremist movements, where internal power struggles often lead to self-destruction.

Despite their dissolution, the Brownshirts' legacy persists in the tactics and ideologies of modern extremist movements. Their use of street violence, intimidation, and populist rhetoric to achieve political ends has been replicated by groups like the Proud Boys, Golden Dawn, and neo-Nazi organizations worldwide. The Brownshirts' normalization of political violence as a tool for change created a blueprint for contemporary extremists, who often adopt similar strategies to disrupt democratic processes. For instance, the January 6, 2021, Capitol riot in the United States echoed the Brownshirts' storming of opposition meetings in the 1920s and 1930s, demonstrating the enduring influence of their methods.

To counter this legacy, it is essential to study the Brownshirts' decline as a cautionary tale. Their dissolution after the Night of the Long Knives underscores the fragility of movements built on extremism and personal loyalty rather than ideology. Modern societies must address the root causes of extremism—economic inequality, social alienation, and political disenfranchisement—to prevent the rise of similar groups. Education plays a critical role; teaching the history of the Brownshirts and their consequences can immunize younger generations against the allure of extremist ideologies. Practical steps include promoting civic engagement, fostering inclusive communities, and strengthening legal frameworks to hold extremist groups accountable.

Comparatively, the Brownshirts' influence on modern extremism also reveals the importance of early intervention. Unlike in the 1930s, today’s governments and civil societies have the tools to monitor and disrupt extremist networks before they escalate into violence. Social media platforms, for example, can be leveraged to counter extremist narratives, though this requires careful balancing with free speech principles. The Brownshirts' rapid rise and fall serve as a reminder that extremism thrives in environments of political instability and economic hardship, making proactive policies to address these issues crucial. By learning from their decline, we can mitigate the risk of history repeating itself.

Understanding Divisive Political Rhetoric: Causes, Impact, and Consequences

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The term "brown shirt politics" originates from the Nazi Party's paramilitary wing, the Sturmabteilung (SA), whose members wore brown uniforms. It has since become a metaphor for authoritarian, fascist, or extremist political movements.

"Brown shirt politics" typically represents far-right, nationalist, and authoritarian ideologies, often characterized by suppression of dissent, use of violence, and the promotion of a single, dominant group or ideology.

Unlike mainstream politics, which often emphasizes democracy, pluralism, and rule of law, "brown shirt politics" prioritizes authoritarian control, often disregards individual rights, and uses intimidation or force to achieve its goals.

Yes, modern examples include extremist groups or movements that advocate for nationalism, racism, or authoritarian rule, often using tactics like street violence, propaganda, and suppression of opposition to gain power.

Societies can protect themselves by upholding democratic values, promoting education and critical thinking, strengthening institutions, and actively countering hate speech, discrimination, and authoritarian tendencies.