The question of whether English classes are politically biased has sparked considerable debate in educational circles, as literature and language instruction often intersect with themes of power, identity, and social justice. Critics argue that the selection of texts, authors, and topics can reflect or promote specific ideological perspectives, potentially marginalizing certain voices or reinforcing dominant narratives. Proponents, however, contend that English classes aim to foster critical thinking and diverse viewpoints, encouraging students to analyze and question the political and cultural contexts of works. This tension highlights the broader challenge of balancing inclusivity, academic rigor, and the inherent subjectivity of literary and cultural studies in shaping students' understanding of the world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Prevalence of Political Bias | Studies suggest English classes can exhibit political bias, but the extent varies widely depending on factors like instructor, curriculum, and geographic location. |

| Sources of Bias | Textbook selection, instructor's personal beliefs, assigned readings, class discussions, and grading criteria can all contribute to bias. |

| Types of Bias | Liberal bias is often cited as more prevalent, but conservative bias can also exist. Bias can manifest in favoring certain political ideologies, historical interpretations, or social issues. |

| Impact on Students | Exposure to biased perspectives can shape students' worldview, critical thinking skills, and political beliefs. It can also lead to self-censorship or discomfort for students with differing views. |

| Arguments Against Bias | English classes focus on literary analysis, not political advocacy. Teachers aim for objectivity and encourage diverse perspectives. |

| Mitigating Bias | Diverse textbook selection, transparent grading criteria, encouraging open dialogue, and promoting critical thinking skills can help reduce bias. |

| Recent Developments | Increased scrutiny of educational content and growing political polarization have heightened concerns about bias in English classes. |

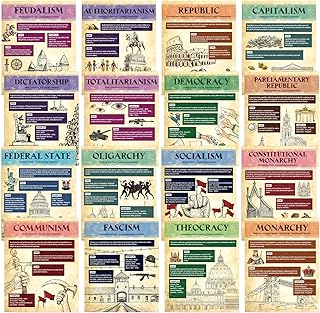

Explore related products

$3.99 $12.95

What You'll Learn

Curriculum Selection: Whose Stories Are Told?

The stories we encounter in English classes shape our understanding of the world, but who decides which narratives deserve a place in the curriculum? This question lies at the heart of the debate surrounding political bias in education. Curriculum selection is a powerful act of gatekeeping, determining whose voices are amplified and whose experiences are marginalized. A quick glance at the canon reveals a dominance of Western, male authors, often at the expense of diverse perspectives. For instance, the works of Shakespeare and Dickens are staples, while authors like Toni Morrison or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie might appear less frequently, if at all. This imbalance raises concerns about the inclusivity and representativeness of the curriculum.

Analyzing the Impact of Curriculum Choices

The selection of texts is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound implications for students' worldview and self-perception. When a curriculum predominantly features stories from a specific cultural or ideological perspective, it can inadvertently reinforce stereotypes and power structures. For example, a curriculum heavy on colonial-era literature might perpetuate a Eurocentric view of history, neglecting the rich narratives of colonized peoples. Conversely, including a diverse range of voices can foster empathy, challenge preconceptions, and provide students with a more nuanced understanding of society. A study by the National Council of Teachers of English found that students exposed to multicultural literature demonstrated increased cultural awareness and improved critical thinking skills.

A Practical Guide to Curriculum Diversification

To address this bias, educators can take proactive steps to diversify the curriculum. Here's a strategic approach:

- Audit Existing Materials: Begin by evaluating the current curriculum. Identify the demographics of authors and characters, noting any patterns or gaps.

- Set Diversity Goals: Establish specific targets for representation, ensuring a balance of gender, ethnicity, cultural background, and ideological perspectives.

- Curate a Balanced Reading List: Introduce works that challenge traditional narratives. For instance, pair classic novels with contemporary responses or adaptations, such as *Wide Sargasso Sea* alongside *Jane Eyre*.

- Incorporate Student Choice: Allow students to select texts that resonate with their interests and identities, empowering them to explore diverse stories.

- Provide Teacher Training: Equip educators with the tools to teach diverse literature effectively, addressing potential biases and encouraging open dialogue.

The Power of Representation in Education

The impact of seeing oneself reflected in the curriculum cannot be overstated, especially for students from marginalized communities. When a young reader encounters a character who shares their background or struggles, it validates their experiences and fosters a sense of belonging. This representation can inspire students to engage more deeply with the material and, by extension, their own education. For instance, a study focusing on African American students found that reading books with Black protagonists significantly improved their reading motivation and self-concept.

In the context of curriculum selection, the question of political bias is inherently tied to issues of power and representation. By consciously choosing to include a variety of stories, educators can create a more inclusive learning environment, one that challenges students to think critically and empathically about the world and their place within it. This approach not only enriches the educational experience but also contributes to a more equitable society, where diverse voices are heard and valued.

Football's Political Power: How the Sport Shapes Global Politics

You may want to see also

Teacher Influence: Shaping Student Perspectives

Teachers wield significant influence in shaping student perspectives, particularly in English classes where literature, rhetoric, and critical thinking intersect. A teacher’s choice of texts, framing of discussions, and implicit or explicit biases can subtly steer students toward specific political interpretations. For instance, assigning *The Communist Manifesto* alongside *Capitalism and Freedom* without balanced context may tilt the scale, depending on how the teacher guides the analysis. This power dynamic raises questions about intentionality and responsibility: Are teachers consciously or unconsciously embedding their political views into lessons?

Consider the analytical approach: When dissecting a novel like *1984*, a teacher might emphasize government surveillance as a critique of authoritarianism, aligning with libertarian perspectives, or focus on the dangers of misinformation, echoing progressive concerns about media literacy. The lens through which the teacher presents the material becomes the student’s starting point for understanding. Research suggests that students aged 14–18 are particularly susceptible to such framing, as their political identities are still forming. A 2020 study by the Brookings Institution found that 62% of high school students reported their teachers’ views influenced their political beliefs.

To mitigate bias, teachers can adopt a comparative strategy, presenting multiple interpretations of a text and encouraging students to evaluate evidence independently. For example, when teaching *To Kill a Mockingbird*, instructors could juxtapose Atticus Finch’s moral stance with critiques of the novel’s "white savior" narrative, fostering nuanced thinking. Practical tips include using a "bias checklist" to ensure diverse perspectives are represented and inviting guest speakers with differing viewpoints. However, caution is necessary: Overcorrecting for bias can lead to superficial discussions that avoid contentious issues altogether.

Persuasively, it’s argued that teachers have a duty to model intellectual honesty, even if it means acknowledging their own biases. A descriptive example is a teacher who openly states, "I lean toward environmental activism, but let’s explore both sides of the climate change debate in this essay assignment." Such transparency empowers students to critically engage with the material rather than passively absorb it. Ultimately, the goal is not to eliminate influence—which is impossible—but to cultivate students who can recognize and question it, whether in the classroom or beyond.

Art of Gracious Declining: Mastering Polite Refusals with Tact and Respect

You may want to see also

Textbook Bias: Hidden Agendas in Content

Textbooks, often seen as neutral vessels of knowledge, can subtly embed political biases that shape students’ perspectives without their awareness. Consider the selection of literary works in English textbooks: a disproportionate inclusion of authors from a particular political or cultural background can marginalize diverse voices. For instance, a textbook that predominantly features Western literature while neglecting global perspectives may inadvertently reinforce a Eurocentric worldview. This bias isn’t always overt; it often lies in the omission of certain narratives or the framing of historical events. Students, trusting the authority of their textbooks, absorb these biases as objective truth, making it crucial to scrutinize the content they consume.

Analyzing the language and framing of textbook content reveals another layer of bias. Descriptive terms like “revolution” versus “rebellion” or “protest” versus “riot” carry political undertones that influence how students interpret events. For example, a textbook describing the Civil Rights Movement as a series of “protests” may emphasize its legality and peaceful nature, while another labeling it as “riots” could imply chaos and illegitimacy. Such linguistic choices are not accidental; they reflect the authors’ or publishers’ political leanings. Teachers and students must engage critically with these texts, questioning why certain words are chosen and what narratives they serve.

A practical step to counteract textbook bias is to supplement assigned readings with diverse materials. Teachers can introduce primary sources, essays, or literary works from underrepresented perspectives to provide a more balanced view. For instance, pairing a traditional textbook’s account of colonialism with indigenous authors’ writings can offer students a counter-narrative. Additionally, encouraging students to compare multiple textbooks on the same topic can highlight discrepancies and biases. This approach not only enriches learning but also fosters critical thinking, enabling students to identify and challenge hidden agendas in content.

Finally, awareness of textbook bias should prompt systemic change. Educational boards and policymakers must prioritize transparency in textbook selection, ensuring that committees include diverse voices to evaluate content for bias. Parents and educators can advocate for open educational resources (OERs), which are often more inclusive and less prone to hidden agendas. By addressing bias at its source, we can create a more equitable learning environment where textbooks serve as tools for enlightenment, not instruments of indoctrination.

Is Islam a Political Ideology? Exploring Religion's Role in Governance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Grading Bias: Favoring Certain Political Views

English classes, often seen as neutral grounds for literary exploration, can inadvertently become arenas where grading bias favoring certain political views seeps into assessments. This bias may manifest when instructors, consciously or unconsciously, reward essays or analyses that align with their own political leanings. For instance, a teacher who leans left might grade more favorably an essay critiquing capitalism through the lens of *The Great Gatsby*, while a right-leaning teacher might prefer an interpretation emphasizing individual responsibility. Such bias undermines the principle of academic objectivity, turning literature into a tool for political validation rather than critical thinking.

To identify grading bias, students and educators can employ a systematic approach. First, examine the rubric: does it prioritize ideological alignment over analytical rigor? Second, compare grades across assignments with varying political undertones. If essays advocating progressive ideas consistently score higher than those with conservative perspectives—or vice versa—bias may be at play. Third, seek peer feedback to determine if the content or the argument’s alignment with the instructor’s views influenced the grade. This methodical scrutiny can reveal patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Addressing this bias requires proactive measures. Instructors should design rubrics that explicitly separate political content from evaluative criteria, focusing instead on clarity, evidence, and logical coherence. For example, an essay on *1984* could be graded based on how well the student analyzes totalitarianism, not whether they condemn or defend it. Additionally, blind grading—removing student names from submissions—can reduce the influence of preconceived notions about a student’s political beliefs. These steps ensure that grades reflect intellectual merit, not ideological conformity.

Ultimately, the goal is to foster an environment where diverse political perspectives are welcomed but not privileged. English classes should encourage students to engage with texts critically, not to echo the instructor’s worldview. By acknowledging the potential for grading bias and implementing safeguards, educators can uphold the integrity of literary analysis and prepare students to navigate complex ideas without fear of penalization for their beliefs. This approach not only promotes fairness but also enriches the educational experience for all.

Is #MeToo a Political Movement? Exploring Its Impact and Influence

You may want to see also

Classroom Discourse: Limiting or Encouraging Debate?

English classrooms often serve as microcosms of broader societal debates, where the selection of texts and the framing of discussions can either amplify or stifle political discourse. Consider the canonical works frequently taught: *To Kill a Mockingbird* by Harper Lee, George Orwell’s *1984*, or Toni Morrison’s *Beloved*. These texts inherently engage with themes of race, surveillance, and historical trauma, yet the way they are taught can either encourage critical thinking or reinforce a single ideological perspective. For instance, a teacher might present *1984* as a cautionary tale against totalitarianism without exploring how its themes resonate in contemporary political surveillance debates, thereby limiting the scope of discussion.

To foster robust debate, educators must adopt a facilitative rather than prescriptive approach. Start by selecting texts that offer multiple interpretations and encourage students to analyze them through diverse lenses. For example, teaching Shakespeare’s *The Tempest* can invite discussions on colonialism, power dynamics, and resistance, depending on the student’s perspective. Pairing this with a modern adaptation, such as Aimé Césaire’s *A Tempest*, can further enrich the dialogue by introducing postcolonial critiques. The key is to structure lessons as open-ended inquiries rather than lectures, allowing students to draw their own conclusions.

However, encouraging debate is not without risks. Unmoderated discussions can devolve into polarization, especially when sensitive topics like systemic racism or gender identity arise. Teachers must establish ground rules that prioritize respect and evidence-based arguments. For instance, require students to cite specific passages from the text or external sources to support their claims. Additionally, model active listening by summarizing opposing viewpoints before responding, demonstrating how to engage constructively with differing opinions. This approach not only fosters intellectual humility but also prepares students for real-world discourse.

A practical strategy to balance openness and structure is the "fishbowl debate" technique. Divide the class into two groups: one participates in the debate while the other observes. After a set time, observers provide feedback on the quality of arguments, the use of evidence, and the tone of the discussion. This method ensures that all students are actively engaged, either as speakers or critical listeners, and promotes self-awareness about their own biases. For younger students (ages 13–15), simplify the process by focusing on smaller, more concrete issues within the text, gradually building up to complex political themes as their analytical skills develop.

Ultimately, the goal of classroom discourse is not to indoctrinate but to empower students to think critically and articulate their views effectively. By carefully selecting texts, structuring debates, and fostering a culture of respect, English teachers can create a space where political bias is not imposed but examined. This approach not only enhances literary analysis but also equips students with the skills to navigate an increasingly polarized world. After all, the ability to engage in thoughtful debate is not just an academic exercise—it’s a civic necessity.

Understanding Ireland's Political System: A Comprehensive Guide to How It Works

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

English classes are not inherently politically biased, but the selection of texts, discussions, and teaching approaches can reflect or introduce political perspectives.

Yes, the selection of literature can reflect political ideologies, but teachers often aim to include diverse perspectives to encourage critical thinking rather than bias.

While some teachers may unintentionally allow personal beliefs to influence lessons, professional standards emphasize neutrality and fostering open discussion.

No, examining political themes in literature is a critical skill, not bias, as long as multiple viewpoints are explored and students are encouraged to form their own opinions.

Students can identify bias by noting if only one perspective is presented, if controversial topics are avoided, or if discussions lack balanced analysis of differing viewpoints.