Anarchism in politics is a philosophical and political theory that advocates for the abolition of all forms of involuntary hierarchy, including the state, capitalism, and other coercive institutions, in favor of a society based on voluntary cooperation, mutual aid, and self-governance. Rooted in the belief that authority is inherently oppressive and unnecessary, anarchism seeks to create a decentralized system where individuals and communities have the autonomy to organize themselves freely. While often misunderstood as chaos or disorder, anarchism emphasizes direct democracy, egalitarianism, and the empowerment of individuals to manage their own lives and resources collectively. Its diverse strands, such as anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism, and anarcho-pacifism, share a common goal of challenging systems of domination and fostering a more just and equitable society.

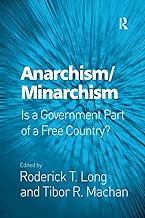

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins and Philosophy: Anarchism's roots in 19th-century thought, emphasizing individual freedom and rejection of authority

- Key Thinkers: Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin, and Goldman shaped anarchist theory and practice

- Types of Anarchism: Includes anarcho-communism, anarcho-capitalism, and anarcho-syndicalism, each with unique goals

- Methods and Tactics: Direct action, mutual aid, and voluntary cooperation as core strategies

- Criticisms and Challenges: Accusations of utopianism, lack of structure, and potential for chaos

Origins and Philosophy: Anarchism's roots in 19th-century thought, emphasizing individual freedom and rejection of authority

Anarchism, as a political philosophy, traces its roots to the 19th century, emerging as a radical response to the social and economic upheavals of industrialization. Thinkers like Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who famously declared "property is theft," laid the groundwork by critiquing capitalist exploitation and centralized authority. This period saw the rise of movements advocating for individual liberty, mutual aid, and the dismantling of hierarchical structures, setting the stage for anarchism’s core tenets.

At its heart, anarchism emphasizes the rejection of coercive authority, whether in the form of state, church, or economic systems. This philosophy is not merely about chaos but about reimagining society based on voluntary cooperation and self-governance. Early anarchists like Mikhail Bakunin and William Godwin argued that human beings are inherently capable of organizing themselves without external control, a belief rooted in Enlightenment ideals of reason and autonomy. Their writings challenged the legitimacy of institutions that impose power, advocating instead for decentralized communities where individuals thrive freely.

The 19th-century context is crucial to understanding anarchism’s development. Industrialization brought immense wealth but also stark inequality, as workers labored in brutal conditions under the rule of factory owners and state elites. Anarchists responded by proposing alternatives such as worker cooperatives, communal living, and direct democracy. For instance, Proudhon’s mutualism sought to abolish profit-driven economies, while Bakunin’s collectivist anarchism emphasized shared ownership of resources. These ideas were not abstract theories but practical solutions to the injustices of the time.

A key takeaway from anarchism’s origins is its insistence on individual freedom as both a moral imperative and a practical necessity. Unlike ideologies that prioritize collective goals at the expense of personal autonomy, anarchism views freedom as the foundation of a just society. This philosophy extends beyond politics into everyday life, encouraging self-reliance, creativity, and resistance to oppression. For those exploring anarchism today, understanding its historical roots offers valuable insights into how it addresses contemporary issues of power, inequality, and human dignity.

To apply anarchism’s principles in modern contexts, consider small-scale experiments like cooperative workplaces or community gardens, which embody its ethos of mutual aid and voluntary association. Engage with anarchist literature, such as Peter Kropotkin’s *Mutual Aid*, to deepen your understanding of its cooperative vision. While anarchism may seem utopian, its historical roots demonstrate that it is a pragmatic response to systemic injustices, offering a timeless call to challenge authority and reclaim individual and collective freedom.

Understanding Progressive Politics: Core Values, Policies, and Societal Impact

You may want to see also

Key Thinkers: Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin, and Goldman shaped anarchist theory and practice

Anarchism, as a political philosophy, owes much of its depth and diversity to the pioneering ideas of key thinkers who challenged authority, hierarchy, and the state. Among these figures, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, and Emma Goldman stand out for their unique contributions to anarchist theory and practice. Each brought distinct perspectives that shaped the movement’s evolution, from its economic foundations to its ethical and social dimensions.

Consider Proudhon, often regarded as the father of anarchism, who coined the phrase "property is theft" in his 1840 work *What is Property?* His analysis of capitalism’s exploitative nature laid the groundwork for mutualism, a system advocating worker-owned cooperatives and reciprocal exchange. Proudhon’s practical approach—such as his proposal for a "people’s bank" to provide credit without interest—offered a blueprint for economic decentralization. His ideas remain relevant for modern cooperatives and credit unions, demonstrating how anarchism can address material inequalities without resorting to state control.

In contrast, Bakunin’s anarchism was fiercely revolutionary, emphasizing the destruction of all hierarchical structures, particularly the state and organized religion. His collectivist vision, outlined in works like *Statism and Anarchy*, prioritized communal ownership of resources and direct action as tools for liberation. Bakunin’s influence is evident in the decentralized, anti-authoritarian tactics of movements like the Spanish Revolution of 1936, where his ideas on voluntary association and federalism were put into practice. His rivalry with Marx within the First International also highlights anarchism’s rejection of centralized power, even in revolutionary contexts.

Kropotkin’s anarcho-communism introduced a more optimistic, science-based perspective, rooted in his observations of mutual aid in human and animal societies. In *Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution*, he argued that cooperation, not competition, is the driving force of progress. Kropotkin’s vision of a stateless society based on voluntary communes and shared resources offered a moral and practical alternative to capitalism and authoritarian socialism. His emphasis on decentralization and local autonomy continues to inspire contemporary movements like the Zapatistas in Mexico, who embody his principles of self-organization and solidarity.

Finally, Emma Goldman brought a uniquely feminist and cultural dimension to anarchism, challenging not only political and economic oppression but also social norms that restricted individual freedom. Through her activism and writings, such as *Anarchism and Other Essays*, Goldman linked anarchism to issues like gender equality, sexual freedom, and artistic expression. Her insistence that true liberation requires both material and personal emancipation expanded anarchism’s scope beyond traditional economic concerns. Goldman’s legacy is visible in modern intersectional movements that fight overlapping systems of oppression, proving anarchism’s adaptability to evolving struggles.

Together, these thinkers illustrate anarchism’s richness as a philosophy that rejects fixed dogmas, embracing instead a pluralistic approach to liberation. Their ideas provide not just historical insight but practical tools for addressing contemporary issues, from economic inequality to social justice. By studying their contributions, one can see anarchism not as a utopian fantasy but as a living, evolving tradition rooted in the pursuit of freedom and equality.

Family Politics: How Values Shape Relationships and Influence Generations

You may want to see also

Types of Anarchism: Includes anarcho-communism, anarcho-capitalism, and anarcho-syndicalism, each with unique goals

Anarchism, often misunderstood as mere chaos, is a diverse political philosophy advocating for the abolition of unjust hierarchies and the state. Within this broad framework, distinct types of anarchism emerge, each with its own vision for organizing society. Three prominent variants—anarcho-communism, anarcho-capitalism, and anarcho-syndicalism—illustrate the breadth of anarchist thought, though their goals and methods diverge sharply.

Anarcho-communism envisions a stateless society where resources are shared freely according to the principle "from each according to ability, to each according to need." Unlike traditional communism, it rejects authoritarian structures, emphasizing voluntary cooperation and decentralized decision-making. For instance, the anarchist regions of Spain during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) practiced collectivized agriculture and worker-managed factories, showcasing the practical application of anarcho-communist ideals. This model prioritizes equality and mutual aid, challenging the notion that centralized control is necessary for resource distribution.

In stark contrast, anarcho-capitalism argues for the abolition of the state while retaining a free-market economy. Proponents, such as Murray Rothbard, contend that private property rights and voluntary exchange can exist without government intervention. Critics, however, argue that this system risks perpetuating hierarchies through wealth inequality. For example, in a purely anarcho-capitalist society, private defense agencies and arbitration firms would replace public institutions, but this raises questions about accessibility and power imbalances. This variant appeals to those who see the market as a self-regulating force but remains contentious within anarchist circles.

Anarcho-syndicalism focuses on labor as the engine of social change, advocating for worker control of production through trade unions. Unlike the other two, it emphasizes direct action, such as strikes and workplace occupations, to dismantle capitalist exploitation. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in the early 20th century exemplifies this approach, organizing across industries to challenge employer dominance. By prioritizing collective bargaining and solidarity, anarcho-syndicalism seeks to build a bottom-up economy, gradually rendering the state obsolete. This strategy offers a practical roadmap for transitioning from capitalism to a stateless society.

While these types of anarchism share a rejection of state authority, their differing approaches to economics and social organization highlight the complexity of anarchist thought. Anarcho-communism prioritizes communal sharing, anarcho-capitalism champions market freedom, and anarcho-syndicalism centers labor empowerment. Each offers a unique lens through which to critique existing power structures and imagine alternatives, demonstrating that anarchism is not a monolithic ideology but a rich tapestry of ideas. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for anyone seeking to engage with anarchist theory or practice.

Understanding Political Liberation: Freedom, Justice, and Societal Transformation Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$10.99 $21.99

Methods and Tactics: Direct action, mutual aid, and voluntary cooperation as core strategies

Anarchism, as a political philosophy, rejects hierarchical structures and advocates for a society based on voluntary association and self-governance. At its core, anarchism emphasizes methods and tactics that empower individuals and communities to take control of their lives directly, without reliance on centralized authority. Among these, direct action, mutual aid, and voluntary cooperation stand out as fundamental strategies. These approaches are not merely theoretical but are practiced in real-world contexts, from labor strikes to community-based disaster relief efforts.

Direct action is a cornerstone of anarchist practice, embodying the principle that individuals should act immediately to address injustices rather than waiting for systemic change. This method bypasses traditional political or legal channels, focusing instead on grassroots interventions. Examples include workers occupying factories to demand better conditions, environmental activists blockading logging sites, or communities organizing rent strikes against exploitative landlords. The effectiveness of direct action lies in its immediacy and visibility, often forcing issues into public discourse and pressuring power structures to respond. However, it requires careful planning and a clear understanding of potential risks, such as legal repercussions or backlash from authorities.

Mutual aid, another key tactic, involves voluntary reciprocal exchange of resources and services for mutual benefit. Unlike charity, which often creates dependency, mutual aid fosters solidarity and collective responsibility. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, mutual aid networks emerged globally, providing food, medical supplies, and emotional support to vulnerable populations. These networks operate on principles of equality and shared decision-making, ensuring that everyone’s needs are addressed without coercion. To implement mutual aid effectively, start by identifying local needs, forming small, decentralized groups, and establishing clear communication channels. Tools like social media platforms or community bulletin boards can facilitate coordination, but face-to-face interactions remain vital for building trust.

Voluntary cooperation complements direct action and mutual aid by emphasizing the importance of consensual collaboration in achieving common goals. Anarchists argue that hierarchies stifle creativity and autonomy, whereas voluntary cooperation allows individuals to contribute freely and meaningfully. This principle is evident in cooperative businesses, where workers collectively manage operations and share profits, or in open-source projects, where contributors collaborate without a central authority. To foster voluntary cooperation, create spaces where decisions are made through consensus-building rather than voting, ensuring that all voices are heard. Encourage diversity in participation and be mindful of power dynamics that might exclude marginalized groups.

Together, these strategies form a cohesive framework for anarchist practice, offering alternatives to state-centric solutions. Direct action challenges oppressive systems, mutual aid builds resilient communities, and voluntary cooperation models a non-hierarchical society. While these methods are not without challenges—such as scaling efforts or countering state repression—they provide tangible pathways toward anarchist ideals. By focusing on actionable steps and real-world applications, individuals and communities can begin to embody the principles of anarchism in their daily lives, creating a foundation for broader societal transformation.

Are Political Action Committees 501c3? Understanding PAC Tax Status

You may want to see also

Criticisms and Challenges: Accusations of utopianism, lack of structure, and potential for chaos

Anarchism, as a political philosophy advocating for the abolition of all forms of hierarchical control, often faces accusations of being inherently utopian. Critics argue that its vision of a stateless, self-governing society is unrealistic, given human nature’s alleged propensity for conflict and competition. This charge of utopianism suggests that anarchism is more of an idealistic dream than a practical blueprint for societal organization. For instance, the belief that communities can function harmoniously without centralized authority is seen by detractors as naive, ignoring historical evidence of power vacuums leading to instability. While anarchists counter that their philosophy is grounded in voluntary cooperation and mutual aid, the utopian label persists, casting doubt on its feasibility in a complex, globalized world.

One of the most persistent criticisms of anarchism is its perceived lack of structure, which critics claim would lead to societal disintegration. Without formal institutions like governments, courts, or police, skeptics argue, there would be no mechanisms to resolve disputes, enforce norms, or protect individual rights. This critique often stems from a misunderstanding of anarchist proposals, which do not advocate for chaos but for decentralized, horizontal structures. For example, anarchist models like consensus decision-making in assemblies or community-based justice systems offer alternatives to traditional hierarchies. However, the absence of a clear, centralized framework leaves many unconvinced, fearing that such systems would struggle to scale or maintain order in diverse, large-scale societies.

The potential for chaos is perhaps the most alarming accusation leveled against anarchism, rooted in the belief that human societies require strong authority to prevent descent into disorder. Critics point to historical examples of power vacuums, such as the collapse of the Soviet Union or periods of warlordism, as evidence of what could happen without a governing body. Anarchists respond by distinguishing their philosophy from mere absence of government, emphasizing voluntary association and self-organization. Yet, the question remains: how would an anarchist society handle crises, external threats, or internal conflicts without a centralized authority? This uncertainty fuels skepticism, as critics argue that even the most well-intentioned communities could fracture under pressure.

To address these criticisms, anarchists must articulate concrete strategies for transitioning to and sustaining a stateless society. For instance, outlining scalable models of decentralized governance, such as federated networks of autonomous communities, could alleviate concerns about structure. Similarly, highlighting successful examples of anarchist principles in practice—like the Zapatista movement in Mexico or Rojava’s democratic confederalism—can counter accusations of utopianism. However, anarchists must also confront the challenge of human fallibility, acknowledging that their vision requires not just systemic change but also cultural shifts toward cooperation and mutual respect. Without such nuance, anarchism risks being dismissed as an idealistic fantasy rather than a viable political alternative.

Massachusetts' Political Leanings: A Deep Dive into Its Progressive Landscape

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Anarchism is a political philosophy that advocates for the abolition of all forms of involuntary hierarchy, including the state, capitalism, and other coercive institutions, in favor of voluntary associations and self-organization.

No, anarchists do not advocate for chaos or lawlessness. Instead, they seek to replace coercive authority with voluntary cooperation, mutual aid, and decentralized decision-making structures.

The core principles of anarchism include opposition to hierarchy, emphasis on individual and collective freedom, voluntary association, mutual aid, and the belief that society can function without a centralized state.

Yes, there are several branches of anarchism, including anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism, anarcho-capitalism (though debated as true anarchism), mutualism, and green anarchism, each with its own focus and strategies.

Anarchists propose organizing society through decentralized, voluntary, and democratic structures such as communes, cooperatives, and federations, where decisions are made collectively and power is distributed equally.