A political scale is a tool used to measure and categorize individuals' or groups' political beliefs and ideologies along a spectrum, typically ranging from left to right. This spectrum often represents varying degrees of government intervention, economic policies, and social issues, with the left generally advocating for greater government involvement, progressive social policies, and wealth redistribution, while the right tends to favor limited government, free markets, and traditional values. Political scales can be one-dimensional, focusing solely on the left-right divide, or multi-dimensional, incorporating additional axes such as authoritarianism vs. libertarianism or globalism vs. nationalism, to provide a more nuanced understanding of political positions. By using these scales, analysts, researchers, and individuals can better comprehend the complex landscape of political ideologies and how they shape public discourse, policy-making, and electoral behavior.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A tool to measure and categorize political beliefs and ideologies. |

| Dimensions | Typically includes economic (left-right) and social (libertarian-authoritarian) axes. |

| Economic Axis | Left (egalitarian, government intervention) vs. Right (free market, individualism). |

| Social Axis | Libertarian (personal freedom, minimal government) vs. Authoritarian (order, regulation). |

| Purpose | To simplify and visualize complex political beliefs. |

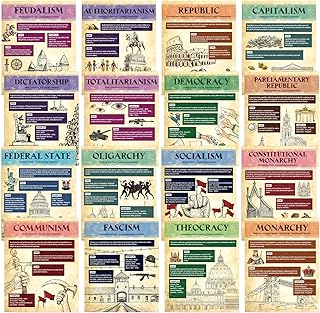

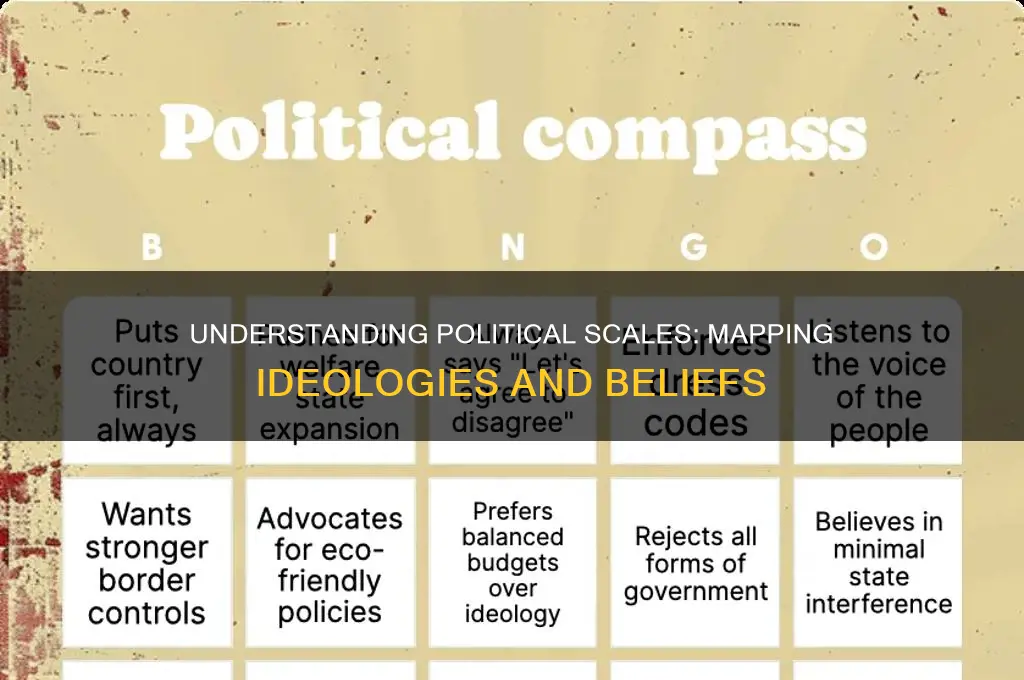

| Common Scales | Nolan Chart, Political Compass, Left-Right Spectrum. |

| Limitations | Oversimplification, cultural biases, lack of nuance in complex ideologies. |

| Usage | Academic research, political campaigns, self-assessment tools. |

| Evolution | Originally linear (left-right), now often multi-dimensional. |

| Cultural Variations | Definitions of "left" and "right" vary across countries and cultures. |

| Online Tools | Websites and quizzes to determine one's position on a political scale. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Left-Right Spectrum: Economic and social policies defining traditional political alignment from socialism to conservatism

- Libertarian-Authoritarian Axis: Measures individual freedom versus government control, independent of economic stances

- Progressive-Conservative Divide: Focuses on societal change versus tradition, often intersecting with cultural issues

- Globalism vs. Nationalism: Evaluates attitudes toward international cooperation versus national sovereignty and isolationism

- Environmental Policies: Assesses stances on climate change, resource management, and sustainability in political frameworks

Left-Right Spectrum: Economic and social policies defining traditional political alignment from socialism to conservatism

The left-right political spectrum is a foundational tool for understanding ideological differences, primarily through the lens of economic and social policies. On the left, socialism advocates for collective ownership of resources and wealth redistribution to reduce inequality. This often translates into policies like progressive taxation, universal healthcare, and robust social safety nets. For instance, Nordic countries like Sweden and Denmark exemplify this approach, combining high taxes with extensive public services, resulting in lower income disparities and high living standards. Conversely, the right, rooted in conservatism, emphasizes individual initiative and free markets. Policies here tend to favor lower taxes, deregulation, and limited government intervention. The United States, with its emphasis on capitalism and smaller government, reflects this ideology, though it often grapples with higher income inequality as a trade-off.

Analyzing the spectrum reveals how economic policies shape societal outcomes. Left-leaning economies prioritize equity, often at the cost of reduced economic growth, while right-leaning economies prioritize efficiency, sometimes exacerbating inequality. For example, a 10% increase in the top marginal tax rate in a socialist-leaning country might fund education reforms benefiting lower-income families, whereas a conservative government might cut corporate taxes to stimulate business investment. These choices reflect deeper philosophical disagreements about the role of the state in economic life.

Social policies further distinguish the left and right, often mirroring their economic stances. The left typically supports progressive social reforms, such as LGBTQ+ rights, abortion access, and multiculturalism, viewing these as essential for equality. In contrast, the right often champions traditional values, emphasizing religious freedom, national identity, and restrictive social norms. For instance, left-leaning countries like Canada have legalized same-sex marriage and implemented affirmative action policies, while conservative nations like Poland have tightened abortion laws and resisted multicultural integration. These divergences highlight how the left-right spectrum extends beyond economics to shape cultural and moral frameworks.

A practical takeaway for navigating this spectrum is to examine how policies align with one’s values. For instance, if reducing poverty is a priority, left-leaning policies like a universal basic income might appeal. Conversely, if fostering entrepreneurship is key, right-leaning tax cuts and deregulation could be more attractive. However, caution is warranted: the spectrum is not absolute, and real-world policies often blend elements from both sides. For example, Germany’s mixed economy combines free-market principles with strong social welfare programs, defying strict left-right categorization. Understanding this nuance is crucial for informed political engagement.

In conclusion, the left-right spectrum serves as a useful, though imperfect, framework for understanding political alignment. By examining economic and social policies through this lens, individuals can better grasp the trade-offs between equity and efficiency, tradition and progress. Whether advocating for socialist redistribution or conservative individualism, recognizing the spectrum’s complexities allows for more nuanced and productive political discourse.

Is Polish Media Politically Biased? Analyzing Poland's News Landscape

You may want to see also

Libertarian-Authoritarian Axis: Measures individual freedom versus government control, independent of economic stances

The Libertarian-Authoritarian Axis is a critical dimension in political scales, focusing on the tension between individual freedom and government control. Unlike economic scales that measure attitudes toward markets or wealth distribution, this axis evaluates how much authority the state should wield over personal choices and behaviors. It’s a spectrum: at one end, libertarians advocate for minimal government intervention, prioritizing personal autonomy; at the other, authoritarians support strong state control to maintain order and enforce societal norms. This axis operates independently of economic beliefs, meaning someone can be fiscally conservative yet socially libertarian, or vice versa.

Consider practical examples to illustrate this axis. A libertarian stance might oppose mandatory seatbelt laws, arguing individuals should decide their own safety measures, while an authoritarian perspective would enforce such laws to reduce public health costs. Similarly, debates over drug legalization highlight this divide: libertarians often support decriminalization as a matter of personal choice, whereas authoritarians may favor prohibition to curb societal harm. These examples show how the axis applies to everyday policies, transcending economic ideologies like capitalism or socialism.

Analyzing this axis reveals its complexity. Libertarians emphasize freedom as a foundational right, often citing John Stuart Mill’s *harm principle*: individuals should act as they please unless harming others. Authoritarians, however, prioritize collective stability, arguing that unchecked freedom can lead to chaos. This tension isn’t binary; many fall in the middle, accepting some government control (e.g., traffic laws) while rejecting overreach (e.g., surveillance). Understanding this spectrum helps explain why people with similar economic views may clash on issues like gun control or privacy rights.

To navigate this axis effectively, ask two key questions: *What freedoms are essential for individual flourishing?* and *Where is government intervention justified?* For instance, libertarians might argue for unrestricted free speech, while authoritarians could support hate speech laws to protect marginalized groups. Balancing these perspectives requires nuance, such as protecting civil liberties while addressing systemic issues. Practical tips include examining historical outcomes of libertarian vs. authoritarian policies (e.g., Prohibition in the U.S. vs. Nordic drug decriminalization) and considering context—what works in a homogeneous society might fail in a diverse one.

Ultimately, the Libertarian-Authoritarian Axis serves as a lens for understanding political disagreements beyond economic frameworks. It challenges us to weigh freedom against order, individual rights against collective welfare. By focusing on this axis, voters and policymakers can better articulate their values and engage in more productive debates. Whether you lean libertarian or authoritarian, recognizing this dimension enriches political discourse and fosters clearer, more informed decision-making.

Understanding Political Fiat: Power, Authority, and Its Implications Explained

You may want to see also

Progressive-Conservative Divide: Focuses on societal change versus tradition, often intersecting with cultural issues

The Progressive-Conservative divide is a fundamental axis on the political scale, pitting advocates of societal change against defenders of tradition. This tension often manifests in cultural issues, where progressives push for inclusivity, diversity, and adaptation to modern realities, while conservatives emphasize preserving established norms, values, and institutions. For instance, debates over same-sex marriage highlight this split: progressives frame it as a matter of equality and human rights, while conservatives argue it undermines traditional family structures. Understanding this dynamic requires examining its roots, manifestations, and implications.

To navigate this divide, consider its intersection with cultural issues as a practical starting point. Progressives tend to support policies like gender-neutral bathrooms, affirmative action, and secular education, viewing them as steps toward a more just and inclusive society. Conservatives, on the other hand, often resist such changes, fearing they erode cultural heritage or disrupt social stability. For example, a progressive might advocate for teaching critical race theory in schools to address systemic inequalities, while a conservative might oppose it as divisive or historically inaccurate. The key is recognizing that both sides draw from deeply held values, even if they clash in practice.

A comparative analysis reveals that this divide is not merely ideological but also generational and contextual. Younger demographics, aged 18–35, are more likely to identify with progressive ideals, influenced by globalization, digital connectivity, and exposure to diverse perspectives. Conversely, older generations, particularly those over 50, often lean conservative, valuing stability and continuity. However, exceptions abound: some younger individuals embrace tradition, while older ones champion change. This variability underscores the importance of avoiding stereotypes and engaging with individuals’ specific beliefs rather than assuming them based on age or background.

Persuasively, bridging the Progressive-Conservative divide requires acknowledging the validity of both change and tradition. Progress without regard for cultural roots risks alienating communities, while unyielding traditionalism stifles innovation and adaptation. A balanced approach might involve incremental reforms that respect tradition while addressing contemporary challenges. For instance, preserving historical monuments while adding context to acknowledge their complex legacies can satisfy both sides. Practical tips include fostering dialogue across ideological lines, focusing on shared values like fairness or community, and avoiding polarizing rhetoric that deepens divisions.

In conclusion, the Progressive-Conservative divide is a dynamic and multifaceted aspect of the political scale, deeply intertwined with cultural issues. By understanding its roots, manifestations, and generational nuances, individuals can navigate this tension more effectively. Whether through comparative analysis, persuasive dialogue, or practical compromises, the goal should be to find common ground that honors both the need for progress and the value of tradition. This approach not only fosters political cohesion but also ensures societies evolve without losing sight of their foundations.

Understanding Political Passivity: Causes, Consequences, and Civic Engagement Decline

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Globalism vs. Nationalism: Evaluates attitudes toward international cooperation versus national sovereignty and isolationism

Political scales often map ideologies along dimensions like left-right or authoritarian-libertarian, but the globalism-nationalism axis offers a distinct lens for understanding contemporary conflicts. At its core, this scale evaluates how individuals and nations balance the benefits of international cooperation against the preservation of national sovereignty and cultural identity. Globalism emphasizes interconnectedness, advocating for open borders, multilateral agreements, and shared solutions to global challenges like climate change or pandemics. Nationalism, in contrast, prioritizes domestic interests, often viewing international institutions as threats to autonomy and local traditions. This tension is not merely theoretical; it shapes policies on trade, immigration, and foreign relations, with tangible impacts on economies, societies, and geopolitical stability.

Consider the European Union as a case study in globalist ideals. By pooling sovereignty, member states have created a single market, a common currency, and coordinated policies on everything from agriculture to human rights. Proponents argue this fosters economic growth, cultural exchange, and collective problem-solving. Critics, however, point to the erosion of national decision-making and the rise of euroskeptic movements as evidence of nationalism’s enduring appeal. Brexit, for instance, was framed as a reclaiming of British sovereignty from Brussels bureaucrats, highlighting the emotional and ideological weight of national identity. Such examples illustrate how the globalism-nationalism scale is not just about policy but about deeply held values and fears.

To navigate this scale effectively, individuals and policymakers must weigh trade-offs. Globalism promises efficiency and innovation through collaboration but risks diluting local cultures and accountability. Nationalism safeguards autonomy but can lead to isolationism, protectionism, and missed opportunities for mutual benefit. A practical approach might involve "dosage" adjustments: embracing globalist principles for issues requiring collective action (e.g., climate agreements) while preserving nationalist safeguards for sensitive areas like cultural heritage or national security. For instance, a country might sign the Paris Agreement while maintaining strict immigration controls—a hybrid strategy reflecting nuanced priorities.

Persuasively, the globalism-nationalism debate often oversimplifies complex realities. It’s not always a binary choice but a spectrum. Countries like Canada or Sweden exemplify "pragmatic globalism," participating in international initiatives while fiercely protecting their social welfare models. Conversely, nations like Hungary or India blend nationalist rhetoric with selective global engagement, such as participating in trade blocs while resisting external cultural influences. These examples challenge the notion that globalism and nationalism are mutually exclusive, suggesting instead that they can coexist in dynamic equilibrium.

In conclusion, the globalism-nationalism scale is a vital tool for understanding modern political fault lines. It forces us to confront difficult questions: How much sovereignty are we willing to cede for collective progress? Can nations preserve their identities in an increasingly interconnected world? By analyzing this scale through specific examples, trade-offs, and hybrid models, we gain actionable insights for balancing cooperation and autonomy. Whether you lean globalist or nationalist, recognizing the validity of both perspectives fosters more informed, empathetic, and effective political discourse.

Understanding Political Attitudes: Shaping Beliefs, Behaviors, and Civic Engagement

You may want to see also

Environmental Policies: Assesses stances on climate change, resource management, and sustainability in political frameworks

Environmental policies serve as a critical lens through which political frameworks address the planet's health, revealing stark contrasts in ideologies and priorities. On one end of the spectrum, progressive policies advocate for aggressive carbon reduction targets, such as achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, while conservative approaches often emphasize economic growth, sometimes at the expense of environmental regulation. For instance, the Green New Deal in the United States proposes a radical overhaul of energy systems, whereas other policies may prioritize fossil fuel industries. These stances reflect deeper philosophical divides: whether humanity should adapt to the environment or harness it for progress.

To evaluate a political framework's commitment to sustainability, examine its resource management strategies. Effective policies integrate circular economy principles, reducing waste and maximizing resource efficiency. For example, the European Union's Circular Economy Action Plan aims to halve residual municipal waste by 2030. In contrast, frameworks lacking such initiatives often perpetuate linear models of extraction, consumption, and disposal, exacerbating resource depletion. Practical steps for citizens include supporting local recycling programs and advocating for policies that incentivize sustainable practices, such as tax breaks for renewable energy adoption.

Climate change stances are a litmus test for a political framework's long-term vision. Progressive policies often align with scientific consensus, endorsing measures like carbon pricing and renewable energy subsidies. Conservative frameworks may question the urgency of climate action or propose technological solutions without systemic change. For instance, while some governments invest heavily in solar and wind energy, others focus on carbon capture technologies, which remain unproven at scale. Individuals can influence this by voting for candidates who prioritize evidence-based climate policies and by reducing personal carbon footprints through actions like adopting plant-based diets or using public transportation.

Sustainability in political frameworks is not just about environmental protection but also social equity. Policies that address environmental justice ensure marginalized communities are not disproportionately affected by pollution or climate impacts. For example, the Just Transition framework seeks to create green jobs for workers displaced by fossil fuel industry declines. Conversely, policies that ignore equity can deepen societal divides. Citizens can engage by supporting organizations that advocate for environmental justice and by holding leaders accountable for inclusive policy design. Ultimately, environmental policies reveal a political framework's values, offering a clear measure of its commitment to both the planet and its people.

Understanding Political Religion: Ideology, Power, and Belief Systems Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political scale is a tool used to measure and categorize political beliefs or ideologies along one or more dimensions, such as left-right, authoritarian-libertarian, or progressive-conservative.

A political scale works by presenting a series of questions or statements that reflect different political viewpoints. Responses are then analyzed to place individuals or groups on a spectrum, often visually represented as a chart or graph.

No, political scales vary in structure and focus. Some use a single dimension (e.g., left-right), while others use multiple dimensions (e.g., the Nolan Chart or Political Compass) to capture more nuanced ideological differences.