A political ruler, often referred to as a leader or head of state, is an individual who holds significant authority and power within a government or political system. This role encompasses various titles such as president, prime minister, monarch, or dictator, each with distinct responsibilities and methods of governance. Political rulers are tasked with making critical decisions that shape the policies, laws, and overall direction of a nation or state, often influencing the lives of their citizens and the international community. Their leadership style, ideology, and decision-making processes can vary widely, ranging from democratic and inclusive approaches to authoritarian and centralized control. Understanding the nature of political rule is essential to comprehending the dynamics of power, governance, and the complex relationship between leaders and the societies they govern.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A political ruler is an individual or group that holds the highest authority and power in a political system, responsible for making and enforcing laws, policies, and decisions that govern a state or territory. |

| Roles | Head of State, Head of Government, or both; symbolizes national unity, represents the country internationally, and ensures the stability and functioning of the government. |

| Types | Monarch (e.g., King, Queen), President, Prime Minister, Dictator, Military Leader, or other forms depending on the political system (e.g., democracy, monarchy, authoritarianism). |

| Power Source | Derived from constitution, election, inheritance (in monarchies), military control, or popular support. |

| Responsibilities | Policy-making, appointing officials, commanding armed forces, managing foreign relations, ensuring economic stability, and upholding the rule of law. |

| Accountability | Varies by system; democratic rulers are accountable to the electorate, while authoritarian rulers may have limited or no accountability. |

| Term Length | Fixed terms (e.g., 4-5 years in democracies) or lifelong (e.g., monarchs, dictators). |

| Decision-Making | Can be autocratic (sole decision-maker) or collaborative (working with legislatures, cabinets, or councils). |

| Legitimacy | Based on legal authority, popular consent, tradition, or force, depending on the political system. |

| Examples | Joe Biden (U.S. President), Narendra Modi (Indian Prime Minister), King Charles III (U.K. Monarch), Xi Jinping (Chinese President). |

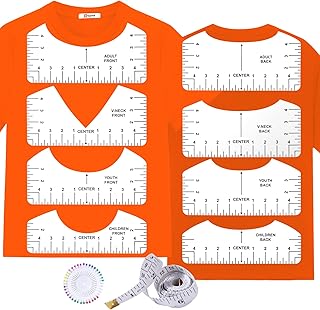

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Role: A political ruler governs a state, making decisions affecting society, economy, and international relations

- Types of Rulers: Includes monarchs, presidents, dictators, and prime ministers, each with distinct powers

- Legitimacy Sources: Derived from elections, heredity, revolution, or divine right, shaping authority

- Responsibilities: Enforcing laws, managing resources, ensuring security, and representing the nation

- Historical Examples: From Alexander the Great to modern leaders, shaping civilizations and policies

Definition and Role: A political ruler governs a state, making decisions affecting society, economy, and international relations

A political ruler, by definition, is an individual or entity vested with the authority to govern a state, wielding power to shape policies and enact decisions that reverberate across society, the economy, and international relations. This role is not merely ceremonial but is deeply entrenched in the fabric of a nation’s functioning, requiring a delicate balance of leadership, strategy, and accountability. Whether a monarch, president, prime minister, or dictator, the political ruler’s actions directly influence the lives of citizens and the trajectory of the state. For instance, a ruler’s decision to invest in infrastructure can stimulate economic growth, while a misstep in foreign policy might lead to diplomatic isolation. Understanding this role is crucial, as it highlights the immense responsibility and potential consequences tied to political leadership.

Analyzing the role of a political ruler reveals a multifaceted position that demands both vision and pragmatism. In the realm of society, rulers must navigate cultural, religious, and ideological divides to foster unity and ensure social cohesion. For example, a ruler addressing income inequality through progressive taxation policies can reduce societal tensions, while neglecting such issues may exacerbate unrest. Economically, their decisions on taxation, trade, and public spending can either propel a nation toward prosperity or plunge it into recession. Consider the contrasting outcomes of leaders like Lee Kuan Yew, whose economic policies transformed Singapore, versus those whose mismanagement led to hyperinflation in Zimbabwe. Internationally, a ruler’s diplomacy or aggression can secure alliances or provoke conflicts, as seen in the contrasting legacies of Nelson Mandela’s reconciliation efforts and Saddam Hussein’s militaristic approach.

To effectively fulfill their role, a political ruler must adhere to certain principles and practices. First, transparency and accountability are non-negotiable, as they build public trust and deter corruption. Second, inclusivity in decision-making ensures that diverse voices are heard, reducing the risk of policies that favor only a select few. For instance, holding public consultations before implementing major reforms can mitigate backlash. Third, adaptability is key, as global dynamics and domestic needs evolve rapidly. A ruler who rigidly adheres to outdated ideologies risks becoming irrelevant, as evidenced by the fall of communist regimes in Eastern Europe. Lastly, prioritizing long-term sustainability over short-term gains—whether environmental, economic, or social—safeguards the future of the state.

Comparatively, the role of a political ruler differs significantly across systems of governance. In democratic societies, rulers are typically elected and held accountable through regular elections, fostering a responsive and representative leadership. In contrast, autocratic rulers wield unchecked power, often prioritizing personal interests over public welfare. For example, democratic leaders like Angela Merkel have navigated crises through consensus-building, while autocrats like Kim Jong-un maintain control through repression. Hybrid systems, such as those in Singapore or China, blend elements of both, offering stability but at the cost of limited political freedoms. This comparison underscores the importance of the governance structure in shaping a ruler’s impact, highlighting the trade-offs between efficiency and accountability.

In conclusion, the role of a political ruler is both complex and consequential, requiring a blend of strategic acumen, ethical leadership, and adaptability. By understanding the scope of their influence—spanning society, the economy, and international relations—citizens can better evaluate their leaders and hold them accountable. Aspiring rulers, meanwhile, must recognize that their decisions have far-reaching implications, demanding a commitment to the greater good over personal or partisan interests. Whether through democratic processes or authoritarian rule, the effectiveness of a political ruler ultimately hinges on their ability to balance power with responsibility, ensuring the prosperity and stability of the state they govern.

Understanding Political Alternation: Power Shifts and Democratic Governance Explained

You may want to see also

Types of Rulers: Includes monarchs, presidents, dictators, and prime ministers, each with distinct powers

Political rulers wield authority over nations, but their powers and roles vary significantly depending on the type of governance. Monarchs, presidents, dictators, and prime ministers each embody distinct leadership styles, shaped by historical context, constitutional frameworks, and cultural norms. Understanding these differences is crucial for grasping how political power operates across the globe.

Consider monarchs, often seen as relics of tradition in modern democracies. In constitutional monarchies like the United Kingdom or Japan, monarchs serve as symbolic heads of state, with limited or no political power. Their role is largely ceremonial, focused on representing national unity and heritage. For instance, Queen Elizabeth II’s reign was defined by her ability to embody stability rather than dictate policy. In contrast, absolute monarchs in countries like Saudi Arabia retain significant executive authority, blending religious and political leadership. This duality highlights how monarchy adapts to different political ecosystems, from figureheads to autocrats.

Presidents, on the other hand, are typically elected leaders with defined terms, though their powers vary widely. In the United States, the president is both head of state and government, commanding substantial executive authority, including military leadership and foreign policy. Conversely, in parliamentary republics like Italy, the president’s role is largely ceremonial, with the prime minister holding real power. This divergence underscores the importance of constitutional design in shaping presidential influence. For citizens, understanding these distinctions is vital for engaging with their political systems effectively.

Dictators represent the extreme end of centralized power, often ruling without constitutional constraints or democratic accountability. Leaders like North Korea’s Kim Jong-un or Syria’s Bashar al-Assad exemplify this, wielding unchecked authority over their nations. Dictatorships thrive on suppression of dissent and control of information, making them resistant to external influence. However, their longevity often depends on internal factors like economic stability or military loyalty. Analyzing dictatorships reveals the fragility of power when it relies on coercion rather than consent.

Prime ministers, prevalent in parliamentary systems, derive their authority from legislative support. In the United Kingdom, the prime minister leads the majority party in Parliament, making them accountable to both their party and the electorate. This dynamic fosters a responsive governance model, as seen in how leaders like Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair navigated public opinion and parliamentary scrutiny. In contrast, prime ministers in coalition governments, such as those in India or Germany, must balance diverse interests, often leading to more consensus-driven policies. This adaptability makes prime ministerial systems both flexible and complex.

Each type of ruler reflects a unique balance of power, accountability, and legitimacy. Monarchs symbolize continuity, presidents embody elected leadership, dictators represent authoritarian control, and prime ministers illustrate parliamentary governance. By examining these roles, one gains insight into the mechanisms of political authority and the diverse ways societies structure leadership. Whether through tradition, election, or force, the nature of a ruler’s power profoundly shapes the nation they govern.

Mastering the Art of Polite Borrowing: Tips for Gracious Requests

You may want to see also

Legitimacy Sources: Derived from elections, heredity, revolution, or divine right, shaping authority

The foundation of a political ruler's authority lies in the perception of legitimacy, a concept that varies widely across cultures, histories, and political systems. Legitimacy is not merely about holding power but about the right to wield it, a distinction that hinges on the source from which this authority is derived. Four primary sources—elections, heredity, revolution, and divine right—have historically shaped the legitimacy of rulers, each carrying its own mechanisms, implications, and challenges. Understanding these sources is crucial for analyzing the stability, acceptance, and effectiveness of political leadership.

Consider elections, the cornerstone of democratic legitimacy. In this system, rulers derive their authority from the consent of the governed, expressed through periodic, free, and fair voting processes. The strength of electoral legitimacy lies in its inclusivity and accountability; rulers are bound to represent the will of the majority while protecting minority rights. However, this source is not without vulnerabilities. Low voter turnout, electoral fraud, or the manipulation of public opinion can erode legitimacy, as seen in cases where leaders cling to power despite questionable mandates. To sustain electoral legitimacy, institutions must ensure transparency, independence, and civic education, fostering a culture where citizens actively participate in the democratic process.

Contrast this with heredity, a source of legitimacy rooted in lineage and tradition. Monarchies, whether absolute or constitutional, rely on the principle of inherited rule, often justified by historical continuity and cultural identity. This system offers stability and predictability, as succession is predetermined, but it can also stifle meritocracy and adaptability. The British monarchy, for instance, has endured by evolving into a symbolic role, while maintaining its legitimacy through ceremonial duties and public affection. Yet, hereditary rule faces increasing scrutiny in an age that values equality and individual rights, prompting debates about its relevance in modern governance.

Revolution, as a source of legitimacy, emerges from the overthrow of existing authority, often in response to oppression, inequality, or injustice. Revolutionary rulers claim legitimacy by asserting their role as agents of change, embodying the aspirations of the masses. The French Revolution and the Bolshevik Revolution are paradigmatic examples, where new regimes justified their power through ideologies of liberty, equality, and socialism. However, revolutionary legitimacy is precarious; it depends on the sustained ability to deliver on promises and maintain popular support. Failure to do so can lead to disillusionment, counter-revolutions, or the descent into authoritarianism, as seen in numerous post-revolutionary states.

Finally, divine right, though less prevalent today, has historically been a potent source of legitimacy, particularly in theocratic or monarchical systems. Rulers claiming divine sanction assert that their authority is ordained by a higher power, making opposition not just treasonous but sacrilegious. This source provided absolute and unchallengeable legitimacy, as seen in medieval Europe or ancient Egypt. However, its effectiveness waned with the rise of secularism and Enlightenment ideals, which prioritized human reason over religious doctrine. Modern remnants of divine right can be observed in certain Islamic republics, where religious law and political authority are intertwined, though this too faces challenges in pluralistic societies.

In practice, these sources of legitimacy are not always mutually exclusive; rulers often blend elements to strengthen their authority. For instance, a monarch might seek popular approval through referendums, or a revolutionary leader might invoke divine blessings to consolidate power. The key lies in aligning the chosen source with the values and expectations of the governed, ensuring that legitimacy is not just claimed but genuinely perceived. As political landscapes evolve, so too must the strategies for establishing and maintaining this crucial foundation of rule.

Is Political Patronage Legal? Exploring Ethics and Legal Boundaries

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Responsibilities: Enforcing laws, managing resources, ensuring security, and representing the nation

A political ruler, whether a president, monarch, or prime minister, is tasked with the monumental responsibility of steering a nation toward stability, prosperity, and unity. Among their core duties are enforcing laws, managing resources, ensuring security, and representing the nation. Each of these responsibilities is interconnected, demanding a delicate balance of authority, foresight, and diplomacy.

Enforcing laws is the backbone of governance. Without it, society descends into chaos. A ruler must ensure that laws are not only written but also applied fairly and consistently. For instance, in democratic systems, this involves overseeing judicial processes, while in authoritarian regimes, it may mean direct control over law enforcement agencies. The challenge lies in preventing abuse of power—a fine line that separates justice from tyranny. Practical steps include regular audits of legal systems, public transparency in court proceedings, and mechanisms for citizen redress. For example, Singapore’s strict enforcement of laws has contributed to its low crime rates, but critics argue it comes at the cost of individual freedoms.

Managing resources is a test of a ruler’s ability to prioritize and plan. This encompasses everything from natural resources like water and minerals to financial assets and human capital. Effective resource management requires long-term vision, often sacrificing immediate gains for future sustainability. Take Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, which manages oil revenues to benefit future generations. In contrast, resource mismanagement, as seen in Venezuela’s oil-dependent economy, can lead to economic collapse. Rulers must also address inequality, ensuring resources are distributed equitably. Practical tips include investing in renewable energy, diversifying economies, and implementing progressive taxation systems.

Ensuring security is both a domestic and international obligation. Internally, it involves protecting citizens from crime, terrorism, and natural disasters. Externally, it means safeguarding national sovereignty and interests in a globalized world. This dual responsibility often requires collaboration with other nations, as seen in NATO’s collective defense agreements. However, security measures must be proportionate to avoid infringing on civil liberties. For instance, the U.S. Patriot Act, while aimed at preventing terrorism, sparked debates over privacy rights. Rulers should focus on intelligence-led security strategies, community policing, and disaster preparedness plans tailored to regional risks.

Representing the nation is a role that extends beyond borders. A ruler serves as the face of their country, embodying its values and aspirations on the global stage. This involves diplomatic engagements, trade negotiations, and participation in international organizations. Effective representation can elevate a nation’s standing, as seen in Angela Merkel’s leadership during the European migrant crisis, which showcased Germany’s commitment to humanitarian values. Conversely, poor representation can isolate a nation, as in North Korea’s diplomatic standoff with the international community. Rulers must cultivate cultural sensitivity, strategic communication skills, and a deep understanding of global dynamics to navigate this responsibility successfully.

In conclusion, the responsibilities of a political ruler are multifaceted, requiring a blend of leadership, strategic thinking, and empathy. Enforcing laws, managing resources, ensuring security, and representing the nation are not isolated tasks but interconnected pillars of effective governance. By mastering these duties, a ruler can foster a stable, prosperous, and respected nation. Practical steps, historical examples, and cautionary tales provide a roadmap for navigating these challenges, ensuring that power is wielded not just with authority, but with wisdom and integrity.

Mastering Respectful Political Disagreements: Strategies for Productive Conversations

You may want to see also

Historical Examples: From Alexander the Great to modern leaders, shaping civilizations and policies

Throughout history, political rulers have wielded immense power, shaping the course of civilizations and leaving indelible marks on policies, cultures, and societies. Alexander the Great, for instance, exemplifies the archetype of a conqueror-ruler whose military campaigns not only expanded his empire but also facilitated the spread of Hellenistic culture across three continents. His strategic vision and relentless ambition created a legacy that endured for centuries, influencing art, philosophy, and governance. Alexander’s ability to blend military might with cultural assimilation offers a blueprint for understanding how rulers can transform the world through both force and finesse.

Contrast Alexander with Queen Elizabeth I of England, whose reign was defined not by territorial expansion but by consolidation and cultural renaissance. Elizabeth’s strategic navigation of religious conflicts, her patronage of the arts, and her cultivation of national identity laid the foundation for England’s emergence as a global power. Her leadership demonstrates that political rule is not solely about conquest; it can also involve fostering unity, stability, and cultural flourishing. Elizabeth’s legacy underscores the importance of adaptability and vision in shaping a nation’s trajectory.

Fast forward to the 20th century, and the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi presents a radically different model of political rule. Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance movement against British colonial rule redefined the parameters of power, proving that moral authority and mass mobilization could dismantle empires without firing a shot. His emphasis on self-reliance, equality, and nonviolence not only secured India’s independence but also inspired civil rights movements worldwide. Gandhi’s example highlights how rulers—or those who challenge ruling systems—can wield influence through principles rather than brute force.

In the modern era, leaders like Angela Merkel illustrate the complexities of political rule in a globalized world. As Germany’s chancellor for 16 years, Merkel’s pragmatic approach to governance, her handling of the European migrant crisis, and her role in stabilizing the European Union demonstrate the challenges of balancing national interests with international responsibilities. Her leadership style, characterized by calm deliberation and consensus-building, offers a contemporary model of how rulers can navigate crises while maintaining democratic values.

These historical examples reveal a spectrum of political rule, from conquest and cultural diffusion to moral leadership and pragmatic governance. Each ruler’s approach reflects the context of their time, yet all share a common thread: the ability to shape civilizations and policies through vision, strategy, and influence. Studying these leaders provides not just a historical perspective but also actionable insights for understanding and evaluating contemporary political leadership. Whether through military might, cultural patronage, moral authority, or diplomatic finesse, the role of the political ruler remains central to the evolution of societies.

Navigating Unity: Practical Strategies to Avoid Church Politics and Foster Harmony

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political ruler is an individual or group that holds the authority to govern a state, country, or other political entity, typically through established institutions and systems of governance.

A political ruler can gain power through various means, including elections, inheritance (in monarchies), military conquest, revolution, or appointment by a governing body, depending on the political system in place.

The primary responsibilities of a political ruler include making and enforcing laws, managing public resources, ensuring national security, representing the state in international affairs, and promoting the welfare of the population.