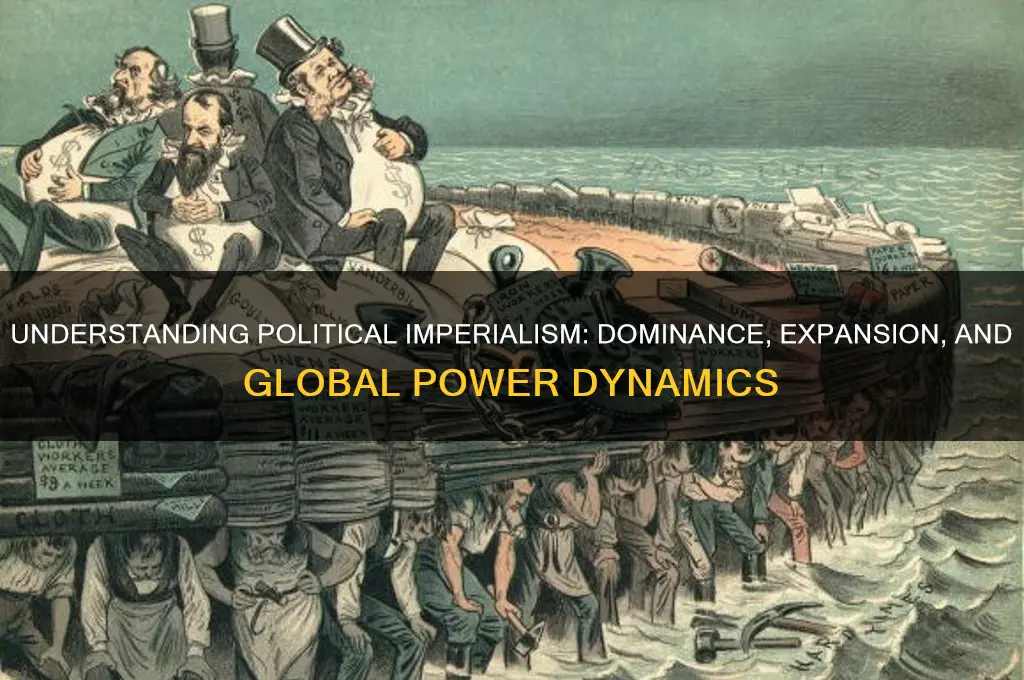

Political imperialism refers to the practice of a powerful nation extending its authority, control, or influence over other territories, often through diplomatic, economic, or military means. It involves the domination of one country over another, typically with the aim of exploiting resources, expanding territorial control, or imposing cultural, political, or economic systems. Historically, imperialism has been driven by motives such as economic gain, strategic advantage, and the spread of ideological or religious beliefs. This phenomenon has shaped global history, leading to the colonization of vast regions, the displacement of indigenous populations, and the creation of lasting geopolitical tensions. Understanding political imperialism is crucial for analyzing power dynamics, historical injustices, and the ongoing impacts of colonial legacies in the modern world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Domination and Control | Establishment of political authority over other territories, often through military force, diplomacy, or economic coercion. |

| Colonial Rule | Direct governance of colonies by the imperial power, imposing its legal, administrative, and cultural systems. |

| Exploitation of Resources | Extraction and control of natural resources, labor, and markets in colonized territories for the benefit of the imperial power. |

| Cultural Suppression | Suppression or marginalization of indigenous cultures, languages, and traditions in favor of the imperial power's culture. |

| Economic Dependency | Creation of economic systems that make colonized territories dependent on the imperial power for trade, investment, and development. |

| Military Presence | Maintenance of military bases and forces in colonized territories to enforce control and suppress resistance. |

| Political Subordination | Limitation or denial of political autonomy and self-governance to colonized peoples. |

| Ideological Justification | Use of ideologies such as the "civilizing mission" or racial superiority to justify imperial domination. |

| Global Influence | Expansion of political, economic, and cultural influence across multiple regions or continents. |

| Resistance and Nationalism | Emergence of resistance movements and nationalist sentiments in colonized territories as a response to imperial rule. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic Exploitation: Extracting resources, labor, and wealth from colonized territories to enrich the imperial power

- Cultural Domination: Imposing the colonizer’s language, religion, values, and customs on indigenous populations

- Political Control: Establishing direct or indirect rule over territories to maintain dominance and authority

- Military Expansion: Using force to conquer and occupy lands, ensuring compliance through coercion

- Ideological Justification: Promoting ideas like civilizing missions to legitimize imperial actions and oppression

Economic Exploitation: Extracting resources, labor, and wealth from colonized territories to enrich the imperial power

Economic exploitation lies at the heart of political imperialism, serving as its lifeblood. It’s a systematic process where imperial powers drain colonized territories of their resources, labor, and wealth, funneling these assets back to the metropole. This isn’t merely theft; it’s a structured, often legalized mechanism designed to sustain and expand the dominance of the imperial power. Consider the Belgian Congo under King Leopold II, where rubber and ivory extraction was enforced through brutal violence, leaving millions dead. The wealth generated didn’t build Congo’s infrastructure or improve its people’s lives—it enriched Belgium and funded Leopold’s lavish projects in Europe. This example underscores a harsh truth: economic exploitation isn’t a byproduct of imperialism; it’s its primary purpose.

To understand how this works, break it down into steps. First, imperial powers identify valuable resources—minerals, agricultural products, or strategic materials—in colonized lands. Second, they establish control through military force, political manipulation, or economic coercion. Third, they implement systems to extract these resources cheaply, often using local labor under exploitative conditions. Fourth, they export the raw materials to the imperial center, where they’re processed and sold at a premium. Finally, the profits are reinvested into the imperial economy, widening the gap between the colonizer and the colonized. For instance, British colonial India was forced to grow cash crops like indigo and opium, which were then shipped to Britain, while famines ravaged the subcontinent due to the diversion of resources. This step-by-step process reveals the calculated nature of economic exploitation.

A comparative analysis highlights the long-term consequences of this exploitation. While imperial powers amassed wealth and industrialized rapidly, colonized regions were left impoverished, their economies distorted to serve foreign interests. Take Latin America, where Spanish and Portuguese colonies were stripped of silver, gold, and agricultural products. The wealth financed Europe’s Renaissance and global expansion, but it left Latin America with underdeveloped industries and unequal land distribution, issues that persist today. In contrast, countries like Japan, which avoided colonization, were able to industrialize on their own terms. This comparison illustrates how economic exploitation not only enriches the imperial power but also stunts the development of colonized territories, creating cycles of dependency and inequality.

Persuasively, it’s crucial to recognize that economic exploitation isn’t confined to history. Modern forms of imperialism continue to extract wealth from developing nations, often under the guise of globalization or free trade. Multinational corporations, backed by powerful nations, exploit cheap labor and resources in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, repatriating profits while leaving local communities with environmental degradation and minimal economic benefits. For example, mining companies in the Democratic Republic of Congo extract cobalt, a critical component in smartphones, under conditions akin to modern slavery. The takeaway is clear: economic exploitation remains a tool of dominance, and addressing it requires challenging the structures that perpetuate global inequality.

Descriptively, imagine a landscape scarred by open-pit mines, forests cleared for monoculture plantations, and workers toiling in hazardous conditions for meager wages. This is the face of economic exploitation in colonized territories. It’s not just about numbers—tonnes of minerals extracted, hectares of land cultivated, or billions of dollars in profit. It’s about the human cost, the environmental devastation, and the erasure of local cultures and economies. In Nigeria, Shell’s oil extraction in the Niger Delta has polluted waterways, destroyed livelihoods, and fueled conflict, while the company’s profits flow out of the country. Such scenes are a stark reminder that economic exploitation is a violent, ongoing process that demands attention and action.

Understanding the Political Left: Core Values, History, and Modern Perspectives

You may want to see also

Cultural Domination: Imposing the colonizer’s language, religion, values, and customs on indigenous populations

The imposition of a colonizer's culture on indigenous populations is a hallmark of political imperialism, often beginning with language. Consider the British Empire's mandate that English be the medium of instruction in Indian schools during the 19th century. This policy not only marginalized native languages like Hindi and Bengali but also created a linguistic hierarchy, where proficiency in English became a prerequisite for social mobility and administrative roles. The result? A generational shift in communication, where indigenous tongues were relegated to informal settings, and English dominated formal discourse, governance, and education.

Religion serves as another potent tool in cultural domination. Spanish conquistadors in the Americas systematically replaced indigenous spiritual practices with Catholicism, often under the guise of "civilizing" missions. Temples were demolished, sacred texts burned, and native rituals criminalized. The construction of churches on sacred sites, such as the Cathedral of Mexico City on the ruins of the Aztec Templo Mayor, symbolized the physical and spiritual conquest. This religious imposition was reinforced through forced conversions, with baptism records from the 16th century showing millions of indigenous people "Christianized" within decades of colonization.

Values and customs are equally targeted in this cultural takeover. In French West Africa, the colonial administration promoted "assimilation," encouraging Africans to adopt French manners, dress, and social norms. Schools taught French etiquette, and traditional attire was discouraged in urban centers. For instance, the wearing of the boubou, a traditional West African garment, was frowned upon in government offices, while European-style suits were incentivized. This cultural erasure extended to family structures, with polygamy, a common practice in many African societies, being legally and socially stigmatized under French rule.

The long-term effects of such cultural domination are profound and multifaceted. In Australia, the Stolen Generations—indigenous children forcibly removed from their families between 1910 and 1970—were raised in institutions where they were forbidden to speak their native languages or practice their traditions. This policy aimed to "breed out" indigenous culture, resulting in a loss of identity and intergenerational trauma. Today, efforts to revive languages like Yolngu Matha and restore cultural practices face significant challenges, as entire generations were disconnected from their heritage.

Resistance to cultural domination has taken various forms, from passive preservation to active rebellion. In Algeria, during French rule, the Arabic language and Islamic faith became symbols of national identity and resistance. Writers like Frantz Fanon highlighted how cultural retention became a political act, with traditional music, clothing, and language serving as tools of defiance. Similarly, the Maori of New Zealand have successfully revitalized their language, te reo Maori, through immersion schools and media, proving that cultural resilience can counter imperialist legacies.

To combat the ongoing impacts of cultural domination, practical steps are essential. Governments and NGOs can fund language revitalization programs, such as the Maori Language Act of 1987, which granted te reo official status and supported its integration into education. Communities can establish cultural safe spaces, like the Native American Language Immersion Schools in the U.S., where children learn indigenous languages alongside academic subjects. Individuals can support indigenous artists, writers, and activists, amplifying voices that challenge colonial narratives. While the scars of cultural imperialism run deep, intentional, collective efforts can reclaim and restore what was lost.

Is Mrs. Dalton Politically Blind? Analyzing Her Stance and Impact

You may want to see also

Political Control: Establishing direct or indirect rule over territories to maintain dominance and authority

Political control, the cornerstone of imperialism, manifests as the deliberate establishment of direct or indirect rule over territories to maintain dominance and authority. This strategy often involves the imposition of a foreign government’s administrative, legal, and military systems on subjugated populations. For instance, during the British Raj in India, the colonial administration replaced local governance structures with a centralized bureaucracy, ensuring British laws and interests prevailed. Direct rule, as seen in this case, allows the imperial power to exert immediate and unchallenged authority, often at the expense of indigenous cultures and systems.

Indirect rule, by contrast, operates through local elites co-opted to serve the imperial power’s interests. In British-controlled Nigeria, for example, traditional leaders were retained but compelled to enforce colonial policies and collect taxes. This approach minimizes administrative costs and reduces resistance by cloaking foreign dominance in the guise of local authority. However, it perpetuates dependency and undermines genuine self-governance. Both methods, direct and indirect, share a common goal: to consolidate political control and extract resources, labor, or strategic advantages from the colonized territory.

Establishing such control requires a multi-faceted approach. Militarily, it involves suppressing resistance through force or the threat thereof. Economically, it entails integrating the colony into the imperial economy, often as a supplier of raw materials or a market for manufactured goods. Culturally, it may involve imposing the colonizer’s language, religion, or education system to erode local identities. For instance, French colonial policy in Algeria included systematic efforts to replace Arabic with French in schools and public life, aiming to create a loyal, assimilated population.

Yet, maintaining dominance is not without challenges. Resistance movements, from Gandhi’s nonviolent campaigns in India to armed struggles in Algeria, have historically undermined imperial control. Modern imperialist strategies often adapt by leveraging economic dependencies or diplomatic influence rather than overt military occupation. The post-colonial era has seen neocolonialism, where former colonies remain politically and economically tethered to their ex-colonizers through trade agreements, debt, or foreign aid. This subtle form of control highlights the enduring nature of imperial dominance, even in the absence of formal rule.

In practice, understanding and countering political control requires a critical examination of power structures. For activists or policymakers, this means identifying mechanisms of dominance—whether military bases, unequal trade agreements, or cultural assimilation policies—and devising strategies to reclaim autonomy. For historians and scholars, it involves documenting the long-term impacts of imperial control on societies, economies, and identities. Ultimately, political control in imperialism is not merely about ruling territories but about shaping the very fabric of subjugated peoples’ lives, often with lasting consequences.

Understanding Political Structures: Frameworks, Power Dynamics, and Governance Systems

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Military Expansion: Using force to conquer and occupy lands, ensuring compliance through coercion

Military expansion, as a cornerstone of political imperialism, relies on the brute application of force to conquer and occupy territories. History is replete with examples where dominant powers have deployed their military might to subjugate weaker nations, often under the guise of civilizing missions, economic exploitation, or strategic security. The Roman Empire, for instance, expanded its borders through relentless military campaigns, imposing its rule across Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Similarly, the British Empire in the 19th century used its naval supremacy to seize control of India, Africa, and parts of Asia, ensuring compliance through a combination of military coercion and administrative control. These cases illustrate how military expansion serves as both a tool and a symbol of imperial dominance.

The process of military expansion is not merely about conquest but also about maintaining control over occupied lands. This involves establishing a permanent military presence, often through garrisons and fortified outposts, to suppress resistance and enforce loyalty. In colonial Africa, European powers like France and Belgium deployed their armies to quell uprisings and secure resource-rich regions. The use of advanced weaponry and tactics against indigenous populations, who often lacked comparable military technology, ensured a lopsided power dynamic. Coercion became the backbone of imperial rule, with local populations forced into compliance through fear, violence, and the dismantling of traditional power structures.

A critical aspect of military expansion is its psychological impact on both the conquerors and the conquered. For the imperial power, military victories reinforce a sense of superiority and justify further aggression. For the subjugated, the constant presence of foreign troops fosters resentment and resistance, often leading to prolonged conflicts. The American occupation of the Philippines in the early 20th century, for example, was met with fierce guerrilla warfare, demonstrating the limits of military coercion in achieving long-term compliance. This dynamic highlights the paradox of military expansion: while it may secure territory, it often sows the seeds of future rebellion.

To implement military expansion effectively, imperial powers must balance brute force with strategic governance. This includes integrating local elites into the administrative system, exploiting existing divisions within the conquered population, and using infrastructure projects to consolidate control. The British in India, for instance, co-opted local rulers through treaties and patronage, while simultaneously building railways and telegraph lines to strengthen their grip. However, such strategies are not foolproof. Over-reliance on military coercion can lead to economic strain, international condemnation, and moral erosion within the imperial power itself.

In conclusion, military expansion as a facet of political imperialism is a double-edged sword. While it enables the rapid acquisition and control of territories, it also creates enduring challenges. The lessons from history are clear: force alone cannot sustain an empire. Successful imperial powers must combine military might with political acumen, economic exploitation, and cultural assimilation. Yet, even then, the inherent violence and injustice of military expansion often lead to its eventual unraveling, as resistance movements and shifting global dynamics undermine imperial dominance. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for analyzing both historical and contemporary forms of political imperialism.

Unveiling Political Skullduggery: Tactics, Deception, and Power Plays Explained

You may want to see also

Ideological Justification: Promoting ideas like civilizing missions to legitimize imperial actions and oppression

Imperial powers have long cloaked their expansionist ambitions in the rhetoric of benevolence, framing conquest as a moral duty rather than a pursuit of dominance. The "civilizing mission" stands as one of history's most insidious ideological tools, a narrative that justified oppression by rebranding exploitation as enlightenment. This concept, deeply embedded in the logic of political imperialism, warrants scrutiny for its enduring influence on global power dynamics.

Consider the European colonization of Africa in the 19th century. Colonial powers like Britain and France portrayed their incursions as acts of altruism, claiming to bring education, Christianity, and "modernity" to what they deemed "backward" societies. This narrative conveniently ignored the violent disruption of indigenous cultures, the extraction of resources, and the imposition of foreign systems of governance. The civilizing mission was not a dialogue but a monologue, a unilateral declaration of cultural superiority that erased the agency and achievements of colonized peoples.

The mechanics of this justification reveal a calculated strategy. By framing imperialism as a moral imperative, colonizers shifted the discourse from questions of power and profit to those of duty and progress. This rhetorical sleight of hand allowed them to silence dissent, both at home and abroad. Critics were cast as obstructionists, hindering the noble work of uplifting the "uncivilized." The irony, of course, is that the very act of colonization often led to the destruction of established social structures, economies, and ways of life, leaving behind a legacy of dependency and inequality.

To dismantle the legacy of the civilizing mission, we must first recognize its persistence in contemporary discourse. Modern interventions, whether economic or military, often echo the same paternalistic tones. The language of "democratization," "development," and "humanitarian aid" can mask neo-imperialist agendas, perpetuating cycles of exploitation under the guise of progress. By interrogating these narratives and amplifying the voices of historically marginalized communities, we can begin to challenge the ideological foundations of imperialism and work toward a more equitable global order.

Machiavelli's Political Outlook: Optimism or Realistic Pessimism?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political imperialism refers to the extension of a country’s power through diplomatic, military, or other means to control or influence other territories, often without formal colonization.

Political imperialism focuses on gaining control over another region’s government or political system, while economic imperialism emphasizes exploiting its resources, markets, or labor for economic gain.

Examples include the British Raj in India, French control over Indochina, and the Soviet Union’s dominance over Eastern Bloc countries during the Cold War.

Political imperialism often leads to the suppression of local cultures, loss of sovereignty, imposition of foreign governance systems, and long-term political instability in colonized regions.