Political infrastructure refers to the foundational systems, institutions, and mechanisms that support the functioning of a political system within a society. This includes the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government, as well as the processes for elections, policy-making, and public administration. It encompasses both formal structures, such as constitutions, laws, and political parties, and informal elements like norms, traditions, and civic engagement. Effective political infrastructure ensures stability, accountability, and the representation of citizens' interests, facilitating governance and the resolution of societal conflicts. Understanding it is crucial for analyzing how power is distributed, decisions are made, and democracy or authoritarianism is sustained in a given political environment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The framework of institutions, processes, and systems that support political activities, governance, and decision-making. |

| Key Components | Government institutions, electoral systems, political parties, civil society, media, and legal frameworks. |

| Purpose | Facilitates the functioning of political systems, ensures stability, and enables citizen participation. |

| Types | Formal (e.g., legislative bodies, courts) and informal (e.g., social norms, community networks). |

| Role in Democracy | Ensures free and fair elections, protects human rights, and promotes accountability. |

| Role in Authoritarianism | Often centralized, limits opposition, and controls information flow. |

| Technological Influence | Digital tools (e.g., social media, e-voting) are reshaping political engagement and communication. |

| Global Variations | Differs across countries based on political systems, cultural norms, and historical contexts. |

| Challenges | Corruption, lack of transparency, polarization, and declining trust in institutions. |

| Importance | Critical for maintaining social order, resolving conflicts, and achieving public policy goals. |

| Recent Trends | Increasing focus on cybersecurity, disinformation, and the role of AI in politics. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Government Institutions: Framework of agencies, departments, and bodies that implement policies and manage public affairs

- Electoral Systems: Mechanisms for voting, representation, and the conduct of free and fair elections

- Legal Frameworks: Laws, constitutions, and regulations that govern political processes and citizen rights

- Public Services: Infrastructure for education, healthcare, transportation, and other essential government-provided services

- Political Parties: Organizations that mobilize voters, shape policies, and compete for political power

Government Institutions: Framework of agencies, departments, and bodies that implement policies and manage public affairs

Government institutions form the backbone of political infrastructure, serving as the operational arms that translate policy into action. These entities—agencies, departments, and specialized bodies—are designed to manage public affairs efficiently, from healthcare and education to defense and economic regulation. Each institution operates within a defined mandate, ensuring that governance is both systematic and accountable. For instance, the U.S. Department of Education oversees national education standards, while the Environmental Protection Agency enforces environmental regulations. Together, these bodies create a framework that sustains the functioning of a state, even as political leadership changes.

Consider the hierarchical structure of government institutions, which often mirrors the complexity of the issues they address. At the top are ministries or departments led by appointed or elected officials, responsible for high-level decision-making. Below them are agencies and bureaus that handle day-to--day operations, such as the Internal Revenue Service in the U.S., which collects taxes and enforces tax laws. This layered system ensures specialization and expertise, but it also requires seamless coordination to avoid inefficiencies. For example, during a public health crisis, health departments must collaborate with emergency management agencies to deploy resources effectively.

A critical aspect of government institutions is their role in policy implementation, which demands both flexibility and consistency. Policies are often crafted with broad objectives, leaving institutions to interpret and execute them within specific contexts. Take the implementation of climate change policies: environmental agencies must balance regulatory enforcement with economic considerations, often requiring adjustments to meet local realities. This adaptive capacity is essential but can also lead to inconsistencies if not managed carefully. Regular audits and performance metrics are tools used to ensure institutions remain aligned with policy goals.

Despite their importance, government institutions are not immune to challenges. Bureaucratic red tape, resource constraints, and political interference can hinder their effectiveness. In developing countries, for instance, underfunded health departments often struggle to deliver essential services, exacerbating public health issues. Similarly, in polarized political environments, institutions may become tools for partisan agendas, undermining their credibility. Strengthening these bodies requires investment in capacity-building, transparency mechanisms, and insulation from short-term political pressures.

Ultimately, the strength of government institutions lies in their ability to adapt to changing societal needs while maintaining stability. They are the bridge between abstract policy goals and tangible outcomes, such as improved infrastructure, accessible healthcare, or reduced crime rates. Citizens interact with these institutions daily, often without realizing it—from obtaining a driver’s license to filing taxes. By understanding their structure and function, stakeholders can better engage with them, advocate for reforms, and hold them accountable. In this way, government institutions are not just administrative tools but vital components of a responsive and effective political infrastructure.

Wisconsin's Political Turmoil: Key Events and Their Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Electoral Systems: Mechanisms for voting, representation, and the conduct of free and fair elections

Electoral systems are the backbone of democratic governance, determining how votes translate into political representation. At their core, these systems define the rules for casting, counting, and converting ballots into seats, shaping the balance of power in legislatures. For instance, proportional representation systems allocate parliamentary seats based on parties’ vote shares, fostering minority inclusion, while first-past-the-post systems prioritize geographic representation, often leading to majority governments. Understanding these mechanisms is critical, as they influence not only election outcomes but also the stability and inclusivity of political systems.

Consider the practical implications of system design. In a mixed-member proportional (MMP) system, like Germany’s, voters cast two ballots: one for a local representative and one for a party. This hybrid approach combines direct constituency representation with proportional allocation, ensuring both local accountability and fair party representation. However, complexity arises in seat distribution, requiring clear thresholds (e.g., 5% of the national vote to qualify for proportional seats) to prevent fragmentation. Such systems demand voter education and robust administrative capacity to function effectively, highlighting the interplay between design and implementation.

Free and fair elections hinge on the integrity of electoral mechanisms. Voter registration processes, ballot secrecy, and independent oversight bodies are non-negotiable components. For example, biometric voter registration, used in countries like Ghana, reduces fraud by verifying identities through fingerprints or facial recognition. Yet, technology alone is insufficient; it must be paired with transparency, such as publicly accessible voter rolls and auditable voting machines. Without these safeguards, even the most sophisticated systems can be undermined, eroding public trust in democratic institutions.

The choice of electoral system also reflects a nation’s political priorities. Majoritarian systems, like those in the U.S. and U.K., prioritize decisive governance but risk marginalizing smaller parties and regions. In contrast, proportional systems, common in Scandinavia, emphasize inclusivity but may lead to coalition governments and slower decision-making. Policymakers must weigh these trade-offs, considering factors like societal diversity, historical context, and administrative capacity. For instance, post-conflict nations often adopt proportional systems to accommodate ethnic or sectarian groups, while stable democracies might opt for majoritarian systems to ensure governmental efficiency.

Ultimately, electoral systems are not one-size-fits-all solutions but tailored frameworks that reflect a nation’s aspirations and challenges. Designing or reforming these systems requires a nuanced understanding of their mechanics, coupled with a commitment to fairness and inclusivity. Whether through proportional representation, ranked-choice voting, or hybrid models, the goal remains the same: to translate the will of the people into legitimate, effective governance. As democracies evolve, so too must their electoral systems, adapting to new technologies, demographic shifts, and the ever-changing demands of citizens.

Understanding LNC Politics: Principles, Impact, and Libertarian Party Dynamics

You may want to see also

Legal Frameworks: Laws, constitutions, and regulations that govern political processes and citizen rights

Legal frameworks serve as the backbone of political infrastructure, providing the rules and structures that define how power is exercised and how rights are protected. At their core, these frameworks consist of laws, constitutions, and regulations that govern political processes and safeguard citizen rights. Without them, political systems would lack the predictability and stability necessary for functioning democracies or any form of governance. For instance, the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1788, not only outlines the separation of powers but also guarantees fundamental rights like freedom of speech and due process, setting a global standard for constitutional governance.

Consider the role of constitutions as the supreme legal documents in many nations. They establish the framework for government, delineate the rights of citizens, and often provide mechanisms for their enforcement. In countries like Germany, the Basic Law (Grundgesetz) explicitly prioritizes human dignity and human rights, influencing legislation and judicial decisions. This example illustrates how a constitution can shape not only political processes but also societal values. However, the effectiveness of a constitution depends on its implementation and the willingness of institutions to uphold it. In nations where constitutional provisions are routinely ignored, political instability and rights violations often follow.

Laws and regulations, while subordinate to constitutions, are equally critical in shaping political infrastructure. They translate broad constitutional principles into actionable rules, governing everything from elections to economic policies. For example, campaign finance laws in the U.K. regulate political donations to prevent undue influence, ensuring a level playing field for candidates. Similarly, data protection regulations like the EU’s GDPR safeguard citizen privacy, a right increasingly threatened in the digital age. These laws demonstrate how legal frameworks adapt to evolving challenges, ensuring that political processes remain fair and rights remain protected.

Yet, the strength of legal frameworks lies not just in their existence but in their enforcement. Independent judiciaries and oversight bodies play a pivotal role in interpreting laws and holding violators accountable. In India, the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review has been instrumental in striking down unconstitutional laws and protecting minority rights. Conversely, in nations where the judiciary is compromised, legal frameworks become tools of oppression rather than protection. This underscores the importance of institutional integrity in maintaining the credibility of legal systems.

In crafting or reforming legal frameworks, policymakers must balance stability with adaptability. Laws that are too rigid risk becoming obsolete, while those that are too flexible can lead to arbitrary governance. For instance, South Africa’s post-apartheid constitution includes provisions for amendment, allowing it to evolve with societal needs while preserving its core principles. Practical tips for strengthening legal frameworks include public consultation in lawmaking, regular judicial training, and the use of technology to enhance transparency. Ultimately, a robust legal framework is not just a set of rules but a living system that reflects and reinforces the values of the society it serves.

Is Flying a Flag Political? Unraveling the Symbolism and Debate

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$86.06 $151.95

Public Services: Infrastructure for education, healthcare, transportation, and other essential government-provided services

Public services form the backbone of a functioning society, yet their role as political infrastructure often goes unrecognized. Education, healthcare, transportation, and other essential services are not merely amenities; they are the physical and institutional frameworks through which governments fulfill their social contract. These systems are designed to ensure equity, accessibility, and opportunity, but their effectiveness hinges on deliberate policy design, adequate funding, and public trust. Without robust public services, even the most democratic governments risk deepening inequality and eroding civic engagement.

Consider education as a prime example. Schools are more than buildings; they are ecosystems of curricula, teacher training, and community involvement. In Finland, a country consistently ranked among the top in global education, the government invests heavily in teacher education, requiring all instructors to hold a master’s degree. This policy, paired with equitable funding across regions, ensures that every child, regardless of socioeconomic status, receives a high-quality education. Contrast this with the United States, where school funding is often tied to local property taxes, perpetuating disparities between affluent and low-income districts. The takeaway? Infrastructure in education is not just about constructing classrooms but about designing systems that prioritize fairness and excellence.

Healthcare infrastructure operates on a similar principle but with life-or-death stakes. Universal healthcare systems, such as those in Canada or the UK, demonstrate how centralized funding and resource allocation can provide broad access to medical services. However, even these systems face challenges like long wait times or resource shortages, highlighting the need for continuous evaluation and adaptation. In low-income countries, where healthcare infrastructure is often fragmented, initiatives like mobile clinics or community health workers have proven effective in bridging gaps. For instance, Ethiopia’s Health Extension Program trains workers to deliver basic services in rural areas, reducing maternal and child mortality rates significantly. The key lesson here is that healthcare infrastructure must be flexible, scalable, and responsive to local needs.

Transportation infrastructure, though often overlooked, is equally critical to public service delivery. Efficient transit systems not only connect people to jobs, schools, and healthcare but also reduce environmental impact and stimulate economic growth. Cities like Copenhagen have prioritized cycling infrastructure, with over 390 miles of dedicated bike lanes, resulting in 62% of residents commuting by bicycle daily. In contrast, car-centric cities like Los Angeles struggle with congestion and pollution, underscoring the importance of forward-thinking urban planning. Governments must invest in sustainable transportation options, such as electric buses or high-speed rail, while ensuring affordability for all citizens.

Ultimately, public services as political infrastructure require a dual focus: building physical systems and fostering institutional trust. When governments invest in education, healthcare, and transportation, they signal their commitment to the well-being of their citizens. However, these investments must be accompanied by transparency, accountability, and public engagement. For instance, participatory budgeting, as practiced in Porto Alegre, Brazil, allows citizens to decide how public funds are allocated, strengthening trust and ensuring that services meet community needs. By treating public services as dynamic, interconnected systems, governments can create infrastructure that not only serves but empowers their people.

Jeffrey Epstein's Political Connections: Unraveling the Dark Web of Influence

You may want to see also

Political Parties: Organizations that mobilize voters, shape policies, and compete for political power

Political parties are the backbone of democratic systems, serving as the primary vehicles for mobilizing voters, shaping policies, and competing for political power. These organizations are not merely groups of like-minded individuals; they are structured entities with clear hierarchies, ideologies, and strategies. At their core, political parties act as intermediaries between the government and the electorate, translating public sentiment into actionable policy proposals. For instance, the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States exemplify how parties aggregate diverse interests into coherent platforms, ensuring that voters have distinct choices during elections.

To effectively mobilize voters, political parties employ a combination of grassroots organizing and mass communication strategies. Door-to-door canvassing, phone banking, and social media campaigns are standard tools in their arsenal. Research shows that personalized outreach increases voter turnout by up to 10%, making these methods indispensable. Parties also leverage data analytics to target specific demographics, tailoring messages to resonate with young voters, seniors, or minority groups. For example, during the 2020 U.S. elections, both major parties used micro-targeting to address issues like student debt and healthcare, which were particularly salient for younger and older voters, respectively.

Policy formulation is another critical function of political parties. They act as think tanks, drafting legislation that aligns with their ideological stances. This process involves extensive research, stakeholder consultations, and internal debates. For instance, the Labour Party in the U.K. has historically championed policies like universal healthcare and workers’ rights, while the Conservative Party emphasizes free markets and fiscal responsibility. These policy frameworks not only differentiate parties but also provide voters with clear alternatives. Parties often release detailed manifestos ahead of elections, offering transparency and accountability to the electorate.

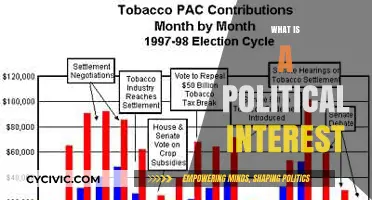

Competition for political power is the lifeblood of political parties. Elections are their battlegrounds, where they vie for control of legislative bodies, executive offices, and local governments. This competition fosters innovation in campaign strategies, policy proposals, and voter engagement. However, it also carries risks, such as polarization and negative campaigning. For example, the increasing use of attack ads in recent elections has been criticized for undermining constructive dialogue. To mitigate these risks, some countries have implemented regulations on campaign financing and advertising, ensuring a level playing field and preserving the integrity of the electoral process.

In conclusion, political parties are indispensable components of political infrastructure, performing vital functions that sustain democratic governance. By mobilizing voters, shaping policies, and competing for power, they ensure that diverse voices are heard and represented. However, their effectiveness depends on ethical practices, transparency, and a commitment to the public good. As democracies evolve, so too must political parties, adapting to new challenges while upholding the principles of fairness and accountability. Their role is not just to win elections but to strengthen the democratic fabric for future generations.

Are Political Ads Public Domain? Legal Insights and Implications

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political infrastructure refers to the systems, institutions, and processes that support the functioning of a political system, including government bodies, electoral systems, political parties, and civic organizations.

Political infrastructure is crucial because it ensures the stability, transparency, and efficiency of governance, facilitates democratic participation, and enables the implementation of public policies.

Key components include legislative bodies, executive branches, judicial systems, electoral commissions, political parties, media, and civil society organizations.

Political infrastructure varies based on a country's political system (e.g., democratic, authoritarian), historical context, cultural norms, and level of economic development.

Yes, political infrastructure can be improved through reforms such as strengthening institutions, enhancing transparency, promoting civic education, and adopting technological advancements to modernize processes.

![The American Democracy Bible: [2 in 1] The Ultimate Guide to the U.S. Constitution and Government | Understand America's Rights, Laws, Institutions, and the Balance of Powers](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71qFOPZK9oL._AC_UY218_.jpg)