A brokered political party refers to a situation within a political party where no single candidate secures a majority of delegates or support during the party's nominating process, typically leading to a contested or brokered convention. In such cases, the party's nomination is not decided by the primary voters alone but is instead negotiated or brokered among party leaders, delegates, and influential figures during the convention itself. This scenario often arises in systems like the United States' presidential primaries, where candidates compete for delegates, and if no clear frontrunner emerges, backroom deals, compromises, and strategic alliances become crucial in determining the party's eventual nominee. Brokered conventions are rare but historically significant, as they highlight the complexities of party dynamics, the influence of power brokers, and the challenges of unifying diverse factions within a political party.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A brokered political party is one in which no single candidate or faction has secured a majority of delegates or support, leading to negotiations and compromises to determine the party's nominee or platform. |

| Occurrence | Typically occurs during a party's nominating convention when no candidate has clinched the required number of delegates in primaries or caucuses. |

| Key Players | Party leaders, delegates, donors, and influential figures negotiate to determine the nominee or party direction. |

| Outcomes | Can result in a consensus candidate, policy compromises, or a power-sharing agreement among factions. |

| Historical Examples (U.S.) | 1924 Democratic National Convention, 1952 Democratic National Convention, and the 1976 Republican National Convention. |

| Modern Relevance | Less common today due to changes in primary systems and increased polarization, but still possible in closely contested races. |

| Risks | Potential for party division, weakened nominee, or voter disillusionment if negotiations are perceived as backroom deals. |

| Benefits | Can foster unity by integrating diverse viewpoints and ensuring broader party representation. |

| Role of Delegates | Delegates play a critical role in negotiations, as their votes determine the outcome in a brokered scenario. |

| Media Influence | Media coverage can shape public perception and pressure party leaders during negotiations. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition: A brokered party lacks dominant candidate, allowing negotiation at convention for nominee selection

- Causes: Divided voter base, multiple strong candidates, or ideological splits trigger brokered outcomes

- Historical Examples: 1924 Democratic Party convention, showcasing prolonged ballots and backroom deals

- Process: Delegates negotiate, form coalitions, and vote repeatedly until a nominee secures majority

- Impact: Risks disunity, but can foster compromise and broader party platform representation

Definition: A brokered party lacks dominant candidate, allowing negotiation at convention for nominee selection

A brokered political party is a term used in the context of political conventions, particularly in the United States, where no single candidate has secured a majority of delegates prior to the party's nominating convention. This scenario arises when a party lacks a dominant frontrunner, leading to a highly contested and uncertain nomination process. In such cases, the party is said to be "brokered," as the selection of the presidential nominee becomes a matter of negotiation, compromise, and strategic maneuvering among delegates, party leaders, and candidates. The absence of a clear leader allows for a more fluid and dynamic convention, where backroom deals, coalition-building, and multiple rounds of voting may determine the eventual nominee.

The concept of a brokered party is rooted in the mechanics of the American political system, where delegates are awarded to candidates based on primary and caucus results. When no candidate amasses enough delegates to clinch the nomination outright, the convention itself becomes the decisive battleground. This situation often occurs when a party is deeply divided, with multiple candidates appealing to different factions or ideological wings. As a result, the convention transforms into a high-stakes forum for negotiation, where candidates and their supporters engage in intense lobbying efforts to win over uncommitted delegates or persuade other candidates to drop out and endorse them.

In a brokered convention, the role of delegates shifts from mere rubber-stamping to active participation in shaping the party's future. Delegates may be bound to vote for a specific candidate on the first ballot based on primary or caucus results, but if no nominee emerges after the initial vote, many delegates become "unbound" and free to support other candidates. This opens the door for strategic alliances, horse-trading, and even the emergence of dark horse candidates who may not have been leading in the pre-convention polls. The process can be chaotic and unpredictable, often requiring multiple rounds of voting until a candidate finally secures the necessary majority.

The brokered party phenomenon highlights the complexities of the American political system and the importance of party unity. While it can be a mechanism for resolving deep divisions within a party, it also carries risks, such as prolonging internal conflicts or alienating supporters of candidates who feel their voices are not heard. Historically, brokered conventions have been relatively rare, as modern polling and media coverage often help establish a clear frontrunner early in the primary season. However, when they do occur, they serve as a reminder of the intricate balance between grassroots democracy and party establishment influence in the nomination process.

Understanding the definition of a brokered party is crucial for grasping the dynamics of presidential nominations in the U.S. It underscores the significance of delegate math, party cohesion, and the role of conventions as more than ceremonial events. For political observers and participants alike, a brokered party scenario represents both a challenge and an opportunity—a challenge to navigate the complexities of negotiation and compromise, and an opportunity to shape the party's direction through direct engagement and strategic decision-making at the convention.

Understanding Political Parties: Their Role, Meaning, and Impact on Society

You may want to see also

Causes: Divided voter base, multiple strong candidates, or ideological splits trigger brokered outcomes

A brokered political party convention occurs when no single candidate secures a majority of delegates during the primary election process, leading to a contested or brokered outcome. This scenario often arises due to a divided voter base, where the electorate is fragmented among multiple candidates, preventing any one contender from achieving dominance. Such divisions can stem from regional, demographic, or policy-based differences, as voters align with candidates who best represent their specific interests or identities. For instance, in a large and diverse country, candidates might appeal strongly to particular states, ethnic groups, or socioeconomic classes, thereby splitting the overall vote and preventing a clear frontrunner from emerging.

Another significant cause of brokered outcomes is the presence of multiple strong candidates within the party. When several contenders possess substantial resources, name recognition, or grassroots support, they can each amass a significant portion of delegates, making it difficult for any one candidate to reach the required majority. This dynamic often occurs in parties with deep benches of experienced politicians, where no single figure naturally rises above the rest. The competition among these candidates can intensify as they vie for delegates, leading to a stalemate that necessitates negotiation or compromise at the convention.

Ideological splits within a party also play a critical role in triggering brokered outcomes. When a party is divided over core principles, policy directions, or values, candidates often emerge as representatives of these competing factions. For example, a party might split between moderate and progressive wings, with each faction rallying behind its preferred candidate. This ideological polarization can prevent the party from coalescing around a single candidate, as neither side is willing to concede to the other. Such divisions are particularly pronounced during periods of significant societal change or when the party is redefining its identity.

The interplay of these factors—a divided voter base, multiple strong candidates, and ideological splits—creates an environment ripe for brokered conventions. In such cases, the outcome is no longer determined by the voters alone but by backroom negotiations among party leaders, delegates, and candidates. These negotiations often involve strategic alliances, policy compromises, or promises of influence in exchange for delegate support. While brokered conventions can lead to unity if handled skillfully, they also carry the risk of deepening divisions if the process is perceived as undemocratic or exclusionary. Understanding these causes is essential for grasping the complexities of brokered political party outcomes and their implications for party cohesion and electoral success.

Refusing Service Based on Political Party: Legal or Discrimination?

You may want to see also

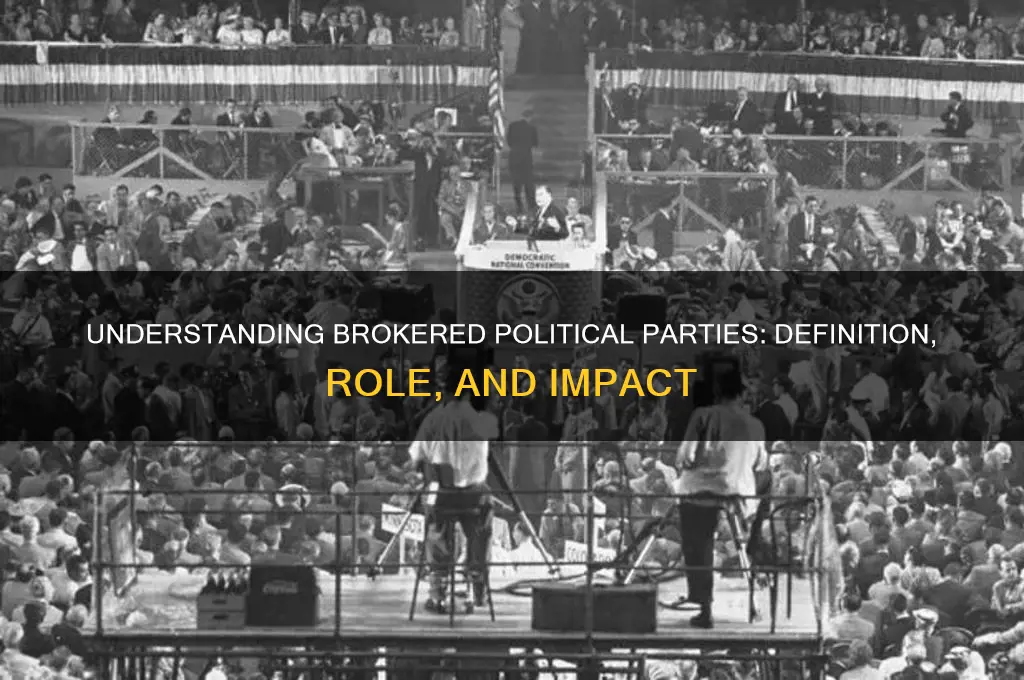

Historical Examples: 1924 Democratic Party convention, showcasing prolonged ballots and backroom deals

The 1924 Democratic National Convention stands as a quintessential example of a brokered political party convention, where no candidate secured a majority of delegates on the initial ballot, leading to prolonged voting rounds and intense backroom negotiations. The convention, held in New York City, was marked by deep divisions within the Democratic Party, primarily between urban, progressive factions and rural, conservative ones. The two leading contenders were William Gibbs McAdoo, former Treasury Secretary and son-in-law of former President Woodrow Wilson, and Governor Al Smith of New York. McAdoo represented the conservative, rural, and anti-Prohibition wing, while Smith championed urban, progressive, and pro-immigrant policies. Neither candidate could clinch the required two-thirds majority, setting the stage for a brokered outcome.

The convention began on June 24, 1924, and quickly descended into deadlock. By the end of the first day, McAdoo led with 454 delegates, while Smith trailed with 247. However, both were far short of the 729 votes needed to secure the nomination. The remaining delegates were scattered among favorite sons and other candidates, reflecting the party’s fragmentation. As the ballots continued—eventually stretching to 103 rounds over 17 days—the convention became a battleground of political maneuvering. Backroom deals, promises of patronage, and ideological compromises dominated the proceedings, as party bosses and delegates sought to break the impasse.

One of the most significant obstacles was the Ku Klux Klan’s influence within the party, particularly among McAdoo’s supporters. Smith’s opposition to the Klan and his Catholic faith made him unacceptable to many Southern and rural delegates. Conversely, McAdoo’s perceived tolerance of the Klan alienated urban and progressive factions. The convention floor erupted in chaos at times, with delegates chanting, booing, and even engaging in physical altercations. The deadlock persisted as neither candidate was willing to withdraw, and neither could attract enough support to win.

The turning point came on the 103rd ballot when both McAdoo and Smith realized that their continued rivalry was damaging the party’s unity. Under pressure from party leaders, McAdoo agreed to withdraw, but only if Smith would also step aside. The nomination ultimately went to a compromise candidate, John W. Davis, a little-known former ambassador and conservative Democrat from West Virginia. Davis was chosen as a safe, uncontroversial figure who could appeal to both factions, though his selection was widely seen as uninspiring. The convention also adopted a platform that avoided contentious issues like Prohibition and the Klan, further highlighting the party’s inability to unite.

The 1924 Democratic Convention exemplifies the mechanics of a brokered political party, where the absence of a clear frontrunner leads to extended ballots and backroom deals. It also underscores the challenges of reconciling deep ideological divides within a party. The convention’s outcome—a compromise candidate and a vague platform—reflected the party’s internal fragmentation and contributed to its overwhelming defeat in the general election. This historical example remains a cautionary tale about the risks of brokered conventions and the importance of party unity in achieving electoral success.

Why Political Leaders Are Essential for Society's Progress and Stability

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Process: Delegates negotiate, form coalitions, and vote repeatedly until a nominee secures majority

In a brokered political party convention, the process of selecting a nominee becomes a complex and dynamic negotiation among delegates. Unlike a typical convention where a clear frontrunner emerges during the primaries, a brokered convention occurs when no candidate secures a majority of delegates beforehand. This triggers a multi-round voting process, where delegates become the key players in determining the party's nominee. The initial phase involves intense negotiations as candidates and their teams lobby delegates, offering concessions, policy alignments, or future political favors in exchange for their support. These negotiations often highlight the candidates' ability to build coalitions and compromise, which are critical skills in governance.

Once negotiations begin, delegates start forming coalitions based on shared interests, regional ties, or ideological alignment. These coalitions can shift rapidly as candidates gain or lose momentum. For instance, a candidate with strong support in one region might partner with another candidate who has influence in a different demographic to consolidate votes. This coalition-building is not static; it evolves with each round of voting as delegates reassess their strategies and the viability of candidates. The process is highly strategic, with weaker candidates often dropping out and releasing their delegates to more viable contenders in exchange for promises of influence in the party or administration.

Voting in a brokered convention occurs in multiple rounds, with each round potentially reshaping the landscape. In the first round, delegates are typically bound to vote for the candidate they were assigned during the primaries. However, if no candidate achieves a majority, subsequent rounds allow delegates to vote freely, often referred to as "brokered" voting. This is where the real maneuvering happens, as candidates and their teams work to sway uncommitted or newly freed delegates. Each round of voting is followed by further negotiations, as candidates attempt to peel away delegates from opponents or solidify their own base.

The repeated voting rounds continue until one nominee secures a majority of delegates. This process can be lengthy and unpredictable, often spanning several days or even weeks. The atmosphere is charged with political maneuvering, backroom deals, and public displays of unity or division. For delegates, the pressure is immense, as their decisions can shape the party's future and its chances in the general election. The candidate who emerges victorious is often seen as a skilled negotiator and coalition-builder, qualities that can be advantageous in a general election campaign.

Throughout this process, transparency and fairness are critical to maintaining the legitimacy of the outcome. Party rules govern how delegates are released, how votes are counted, and how disputes are resolved. Despite these rules, the brokered convention process is inherently chaotic and reliant on human interaction, making it a unique and high-stakes event in political party dynamics. Ultimately, the goal is not just to select a nominee but to unify the party behind a candidate who can appeal to a broad spectrum of voters in the upcoming election.

Divided We Stand: Unraveling the Roots of Political Polarization

You may want to see also

Impact: Risks disunity, but can foster compromise and broader party platform representation

A brokered political party, often associated with brokered conventions in the context of presidential nominations, occurs when no single candidate secures a majority of delegates prior to the party's nominating convention. This scenario shifts the decision-making power to party leaders, delegates, and power brokers, who negotiate and compromise to select a nominee. The impact of such a process is multifaceted, presenting both risks and opportunities for the party involved. One of the most significant risks is the potential for disunity. When no clear frontrunner emerges, factions within the party may rally behind different candidates, leading to deep divisions. These fractures can persist beyond the convention, weakening the party's ability to unite behind the eventual nominee and potentially alienating voters who feel their preferred candidate was unfairly sidelined.

However, a brokered party process can also foster compromise, which is increasingly rare in polarized political landscapes. In a brokered scenario, candidates and their supporters are forced to negotiate, often resulting in a nominee who is acceptable, if not ideal, to a broader spectrum of the party. This compromise can appeal to moderate voters and independents, who may view the party as more pragmatic and less ideologically rigid. Additionally, the negotiation process can lead to a more inclusive party platform, as candidates may need to incorporate elements of their rivals' agendas to secure support from their delegates.

Another aspect of the impact is the potential for broader party platform representation. In a brokered convention, lesser-known candidates or those representing specific ideological wings of the party may gain influence by becoming kingmakers. This can result in a platform that reflects a wider range of perspectives, making the party more representative of its diverse membership. For example, issues championed by progressive or conservative factions within the party may receive greater attention, ensuring that the eventual nominee addresses a broader array of concerns.

Despite these potential benefits, the risk of disunity remains a critical concern. The prolonged and public nature of brokered negotiations can expose internal conflicts, providing ammunition for opponents and creating a perception of chaos. Moreover, if delegates or party leaders are seen as overriding the will of primary voters, it can lead to disillusionment among the party base. This disillusionment can depress voter turnout in the general election, as supporters of losing candidates may feel disengaged or resentful.

In conclusion, the impact of a brokered political party is a double-edged sword. While it risks exacerbating disunity and internal conflicts, it also holds the potential to foster compromise and create a more inclusive party platform. The outcome largely depends on how effectively party leaders manage the process and whether they can transform a divisive scenario into an opportunity for unity and broader representation. Parties navigating such a situation must tread carefully, balancing the need for consensus with the imperative to respect the diverse voices within their ranks.

The Origins of Political Systems: Tracing the Dawn of Governance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A brokered political party refers to a situation where no single candidate secures a majority of delegates or support within the party during a nominating process, such as a presidential primary or convention. This leads to negotiations and compromises among party leaders, delegates, and candidates to determine the party's nominee.

In a brokered convention, delegates who were pledged to specific candidates during primaries or caucuses gather to vote on the party's nominee. If no candidate has a majority on the first ballot, delegates may shift their support to other candidates in subsequent rounds, leading to backroom deals and alliances until a nominee is chosen.

A brokered party can lead to internal divisions, as different factions within the party may have conflicting interests. It can also result in a weakened nominee who lacks broad support, potentially harming the party's chances in the general election. However, it can also force compromise and unity if handled effectively.