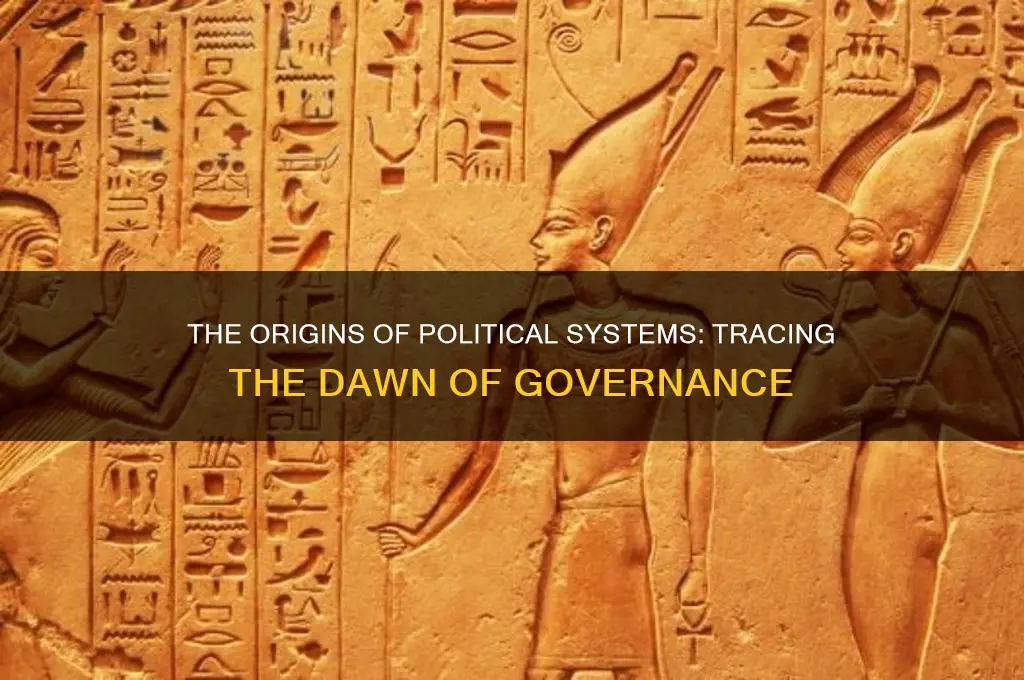

The question of when politics began is deeply intertwined with the origins of human social organization and cooperation. While it’s challenging to pinpoint an exact date, the roots of politics can be traced back to the emergence of early human societies, where individuals began forming groups to manage resources, resolve conflicts, and make collective decisions. Evidence suggests that rudimentary political structures, such as tribal councils and leadership hierarchies, existed as early as the Neolithic period, around 10,000 BCE, as humans transitioned from nomadic lifestyles to settled agricultural communities. The development of cities and civilizations, such as those in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt around 3000 BCE, marked a significant evolution in political complexity, with the establishment of formal governance systems, laws, and centralized authority. Thus, politics, in its earliest forms, began as a natural outgrowth of human cooperation and the need to organize societies for survival and prosperity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Earliest Evidence of Political Organization | Archaeological evidence suggests early forms of political organization emerged around 10,000 BCE with the development of agriculture and permanent settlements. |

| First Known Governments | Sumerian city-states in Mesopotamia (circa 4000-3000 BCE) are considered the first known governments with codified laws and centralized authority. |

| Development of Political Philosophy | Early political thought emerged in ancient civilizations like China (Confucius, 551-479 BCE), India (Arthashastra, 4th century BCE), and Greece (Plato, 428-348 BCE; Aristotle, 384-322 BCE). |

| Formalization of Political Systems | The rise of empires (e.g., Persian, Roman) and the development of complex bureaucracies further formalized political systems. |

| Modern Political Systems | The emergence of nation-states and democratic principles began in the 17th and 18th centuries, influenced by thinkers like Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. |

| Global Spread of Democracy | The 20th century saw the widespread adoption of democratic systems, though authoritarian regimes persist in many regions. |

| Contemporary Political Landscape | Characterized by globalization, digital communication, and the rise of transnational political issues (e.g., climate change, human rights). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Early Human Societies and Power Structures

The origins of politics are deeply rooted in the development of early human societies, where the need for organization, resource management, and conflict resolution gave rise to rudimentary power structures. As humans transitioned from nomadic hunter-gatherer bands to more settled communities, the complexity of social interactions increased, necessitating systems of authority and decision-making. These early power structures were often informal, based on kinship ties, personal charisma, or skill, but they laid the groundwork for what would later become formalized political systems.

In hunter-gatherer societies, power was typically decentralized, with leadership roles emerging organically based on expertise in hunting, foraging, or conflict resolution. Elders or skilled individuals often held influence due to their experience and knowledge, but their authority was not absolute. Decisions were frequently made through consensus, with group discussions playing a central role in resolving disputes or planning actions. This egalitarian approach reflected the relatively small and mobile nature of these societies, where survival depended on cooperation and shared resources.

The advent of agriculture around 10,000 BCE marked a significant shift in human social organization and power dynamics. The establishment of permanent settlements and the accumulation of surplus resources led to population growth and increased social stratification. In these early agrarian societies, power began to concentrate in the hands of individuals or groups who controlled land, labor, and resources. Chiefs, priests, or tribal leaders emerged as central figures, often legitimizing their authority through claims of divine favor, hereditary rights, or military prowess. These leaders played crucial roles in organizing labor, managing resources, and maintaining social order, effectively becoming the first political rulers.

As societies grew larger and more complex, power structures became more formalized. The development of cities in ancient civilizations like Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley saw the rise of centralized governments with distinct hierarchies. Kings, pharaohs, and emperors wielded absolute authority, supported by bureaucracies, religious institutions, and military forces. These early states were often theocratic, blending political and religious power to reinforce legitimacy. Laws, taxation systems, and public works projects further solidified the authority of rulers, demonstrating the emergence of organized political systems designed to manage large-scale societies.

The study of early human societies reveals that politics, in its most basic form, began as a response to the practical needs of social organization and resource management. From the informal leadership of hunter-gatherer bands to the centralized authority of ancient states, power structures evolved in tandem with societal complexity. These early political systems were not merely about control but also about ensuring survival, cooperation, and stability in an increasingly interconnected world. Understanding these origins provides valuable insights into the foundational principles of politics and governance that continue to shape human societies today.

Political Affiliations and Water Authorities: A Global Governance Perspective

You may want to see also

Emergence of Organized Governments in Ancient Civilizations

The emergence of organized governments in ancient civilizations marks a pivotal moment in the history of politics, as human societies transitioned from small, kinship-based groups to larger, more complex structures. This transition began around 3500 BCE in Mesopotamia, often referred to as the "Cradle of Civilization." The development of agriculture and permanent settlements led to surplus resources, population growth, and the need for systems to manage these new dynamics. Early Mesopotamian city-states like Uruk and Ur established centralized authorities, with rulers who oversaw resource distribution, resolved disputes, and organized labor for large-scale projects like irrigation systems and temples. These rulers, often seen as divine or semi-divine, laid the foundation for hierarchical governance and the concept of political authority.

In ancient Egypt, organized government emerged around 3100 BCE with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under King Narmer. The pharaohs, considered gods on earth, wielded absolute power and were the central figures of a highly structured bureaucracy. Egypt's government was characterized by its ability to manage vast territories, construct monumental architecture like the pyramids, and maintain social order through a system of laws and religious ideology. The Nile River's predictable flooding and fertile lands allowed for agricultural surplus, which sustained a specialized workforce, including scribes, priests, and administrators, further solidifying the state's organizational capabilities.

The Indus Valley Civilization (c. 2600–1900 BCE) in present-day India and Pakistan also developed organized governance, though its political structure remains less understood due to the lack of deciphered written records. Cities like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa exhibited remarkable urban planning, with standardized brick houses, drainage systems, and granaries, suggesting a centralized authority capable of coordinating large-scale projects. Evidence of trade networks and uniform weights and measures indicates a level of political organization aimed at economic stability and social cohesion.

In ancient China, the emergence of organized government is closely tied to the Xia Dynasty (c. 2070–1600 BCE), though historical records from this period are debated. The Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE) provides clearer evidence of a centralized state, with kings who ruled through a combination of military power, religious rituals, and administrative systems. The Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) introduced the "Mandate of Heaven," a political philosophy justifying rule based on moral authority, which influenced Chinese governance for millennia. These early Chinese states developed systems of law, taxation, and public works, reflecting the growing complexity of political organization.

Finally, in the Americas, the Olmec Civilization (c. 1500–400 BCE) in Mesoamerica is considered one of the earliest societies to develop organized governance. While less is known about their political structure, their construction of monumental architecture and development of a writing system suggest a centralized authority. Later civilizations like the Maya and Aztec built on these foundations, creating sophisticated systems of governance with rulers, bureaucracies, and legal codes. These ancient civilizations demonstrate that the emergence of organized governments was a global phenomenon, driven by the need to manage resources, maintain order, and coordinate collective efforts in increasingly complex societies.

How Political Parties Influence and Shape Public Policy Decisions

You may want to see also

Role of Philosophy in Political Thought Development

The origins of politics can be traced back to the earliest human societies, where decisions about resource allocation, conflict resolution, and social organization were necessary for survival. However, the systematic study and development of political thought are deeply intertwined with the emergence of philosophy. Philosophy, as a disciplined inquiry into the nature of reality, ethics, and human existence, provided the intellectual framework within which political ideas could be articulated and debated. The role of philosophy in political thought development is thus foundational, offering both the tools and the concepts that have shaped political theories across civilizations.

One of the earliest and most influential contributions of philosophy to political thought comes from ancient Greece. Thinkers like Plato and Aristotle laid the groundwork for Western political philosophy. Plato’s *Republic* explores the ideal state, governed by philosopher-kings who possess knowledge of the Form of the Good, while Aristotle’s *Politics* examines various forms of government and argues for the importance of ethics in political life. These works not only introduced enduring questions about justice, authority, and the common good but also established philosophy as a critical method for analyzing political structures. Their ideas continue to influence debates on the role of reason, virtue, and the state in shaping societies.

Philosophy also played a pivotal role in the development of political thought during the Enlightenment, a period marked by a shift toward reason, individualism, and skepticism of traditional authority. Thinkers like John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Immanuel Kant used philosophical reasoning to challenge monarchical power and advocate for concepts such as natural rights, social contract, and the separation of powers. Locke’s *Two Treatises of Government*, for instance, argued that legitimate political authority derives from the consent of the governed, a principle that became central to democratic theory. These philosophical contributions not only reshaped political discourse but also inspired revolutionary movements, including the American and French Revolutions.

In addition to Western traditions, philosophy has been instrumental in shaping political thought in other cultures. Confucian philosophy, for example, emphasized the moral cultivation of rulers and the importance of harmony in society, influencing political systems in East Asia for centuries. Similarly, Islamic philosophy, drawing on thinkers like Al-Farabi and Ibn Rushd (Averroes), explored the relationship between religion, reason, and governance, contributing to the development of political theories in the Islamic world. These diverse philosophical traditions demonstrate how political thought has been enriched by varied intellectual approaches to questions of power, justice, and the common good.

Finally, contemporary political thought continues to be deeply informed by philosophical inquiry. Modern and postmodern philosophers, such as John Rawls, Michel Foucault, and Hannah Arendt, have addressed issues like justice, power dynamics, and the nature of political participation. Rawls’ *A Theory of Justice* revitalized debates about fairness and equality, while Foucault’s analyses of power and discourse have challenged traditional understandings of political institutions. Arendt’s work on totalitarianism and the public sphere highlights the importance of philosophical reflection in understanding the complexities of modern politics. Through these contributions, philosophy remains a vital force in the ongoing development of political thought, providing both critical perspectives and normative frameworks for addressing contemporary challenges.

In conclusion, the role of philosophy in political thought development is indispensable. From ancient Greece to the present day, philosophical inquiry has provided the conceptual tools and intellectual frameworks necessary for understanding and shaping political systems. By examining fundamental questions about human nature, ethics, and governance, philosophy has not only influenced the evolution of political theories but also guided practical efforts to create just and equitable societies. As such, the study of philosophy remains essential for anyone seeking to comprehend the origins, development, and future of politics.

Why Write Political Poems: Art, Activism, and Amplifying Voices

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Influence of Religion on Early Political Systems

The origins of politics are deeply intertwined with the development of human societies, and religion played a pivotal role in shaping early political systems. As communities transitioned from nomadic lifestyles to settled agricultural societies, the need for organized governance emerged. Religion provided the moral and ideological framework that justified authority, established social hierarchies, and maintained order. In many ancient civilizations, rulers derived their legitimacy from divine sanction, claiming to be appointed or descended from gods. This divine right of kings was a cornerstone of political power in societies such as ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley, where religion and governance were inseparable.

In ancient Mesopotamia, for example, the concept of kingship was intrinsically linked to the divine. Rulers were seen as intermediaries between the gods and the people, tasked with upholding cosmic order (known as *ma’at*). Temples served not only as religious centers but also as administrative hubs, collecting taxes, storing resources, and distributing wealth. The Code of Hammurabi, one of the earliest legal codes, was presented as a gift from the gods to the king, reinforcing the idea that laws were divinely ordained. This fusion of religion and politics ensured that authority was both sacred and unchallengeable, as questioning the ruler was tantamount to defying the gods.

Similarly, in ancient Egypt, pharaohs were considered living gods, embodying the divine on earth. Their role was to maintain *ma’at*, the cosmic balance essential for prosperity and harmony. Religious rituals, such as the pharaoh’s coronation and annual festivals, were political acts that reinforced their authority. The construction of monumental temples and pyramids further solidified the connection between religion and political power, as these structures symbolized the pharaoh’s divine favor and ability to mobilize resources. Religion, therefore, was not just a spiritual force but a political tool that legitimized rule and unified society under a common belief system.

In the Indus Valley Civilization, while less is known about their religious practices due to the lack of deciphered texts, evidence suggests that religion played a significant role in governance. Urban planning, with its emphasis on cleanliness, drainage systems, and standardized weights and measures, reflects a centralized authority likely influenced by religious principles. The presence of ritual baths and altars in cities like Mohenjo-Daro indicates that religious practices were integrated into public life, possibly serving to legitimize the ruling elite’s decisions and maintain social cohesion.

The influence of religion on early political systems extended beyond legitimizing rulers; it also shaped laws, social structures, and cultural norms. In ancient Israel, for instance, theocratic governance was based on the belief that Yahweh had chosen the Israelites and provided them with a moral code (the Torah). Kings like David and Solomon ruled under the premise that they were fulfilling God’s will, and their authority was contingent on adherence to religious laws. This model of theocracy demonstrated how religion could provide both the ethical foundation and the institutional framework for political systems.

In conclusion, religion was a fundamental force in the development of early political systems, offering legitimacy to rulers, structuring societies, and providing moral and legal frameworks. From the divine kings of Mesopotamia and Egypt to the theocratic governance of ancient Israel, the interplay between religion and politics was central to the emergence of organized governance. As societies evolved, the influence of religion on politics persisted, shaping the course of human history and leaving a lasting legacy on modern political thought.

Will Ferrell's SNL Political Characters: Satire, Humor, and Legacy

You may want to see also

Evolution of Political Institutions in City-States

The evolution of political institutions in city-states marks one of the earliest and most significant developments in the history of politics. City-states, such as those in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley, emerged around 3500 to 2500 BCE as humanity transitioned from nomadic lifestyles to settled agricultural communities. These early urban centers became hubs of economic, social, and political activity, necessitating the creation of organized systems to manage resources, resolve disputes, and maintain order. The political institutions of city-states were often centered around a ruler or council, with authority derived from divine legitimacy, military power, or communal consensus. These rudimentary structures laid the groundwork for more complex governance systems.

In Mesopotamia, city-states like Uruk and Lagash developed some of the earliest known political institutions, including codified laws and administrative bureaucracies. The Sumerian king Urukagina of Lagash (circa 2350 BCE) is credited with implementing reforms aimed at reducing corruption and ensuring fair resource distribution, demonstrating an early attempt at institutionalized governance. Similarly, the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE) in Babylon represents a significant milestone in legal and political organization, providing a framework for justice and administration that influenced later civilizations. These institutions were often tied to temple complexes, which served as both religious and administrative centers, reflecting the intertwined nature of politics and religion in early city-states.

In ancient Greece, city-states like Athens and Sparta showcased distinct political evolutions. Athens, often regarded as the birthplace of democracy, transitioned from oligarchy to a system where citizen participation in decision-making became a cornerstone of governance. The reforms of Solon (circa 594 BCE) and Cleisthenes (circa 508 BCE) established institutions like the Assembly and Council of 500, allowing male citizens to debate and vote on laws. In contrast, Sparta maintained a dual kingship and an oligarchic system focused on military discipline. These Greek city-states highlight the diversity of political institutions that emerged in response to unique social, economic, and cultural contexts.

The city-states of the Italian Renaissance, such as Florence and Venice, further illustrate the evolution of political institutions. Florence, under the Medici family, developed a complex system of patronage and republican governance, blending elements of oligarchy and civic participation. Venice, on the other hand, established a sophisticated republic with a Doge and a Great Council, emphasizing stability and trade. These institutions reflected the growing complexity of urban societies and the need for systems that could balance power, manage commerce, and maintain civic order.

Throughout history, the evolution of political institutions in city-states has been driven by the need to address challenges such as resource management, social cohesion, and external threats. From theocratic governance in ancient Mesopotamia to democratic experiments in Athens and the republican models of Renaissance Italy, these institutions adapted to the changing demands of their environments. The legacy of city-state political systems can be seen in modern governance structures, as they pioneered principles of law, representation, and administration that continue to shape political thought and practice today.

ACLU's Political Independence: Uncovering Ties to Parties or Neutrality?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Politics is believed to have begun with the formation of the first human societies, around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, during the Neolithic Revolution when people transitioned from nomadic lifestyles to settled agricultural communities.

Formal political systems, such as governments, emerged around 3500 to 3000 BCE with the rise of ancient civilizations like Sumer in Mesopotamia, which developed organized states with laws, rulers, and administrative structures.

The concept of politics as a structured field of thought and practice began to take shape in ancient Greece, particularly with philosophers like Plato and Aristotle around the 5th and 4th centuries BCE, who analyzed governance, power, and the nature of the state.