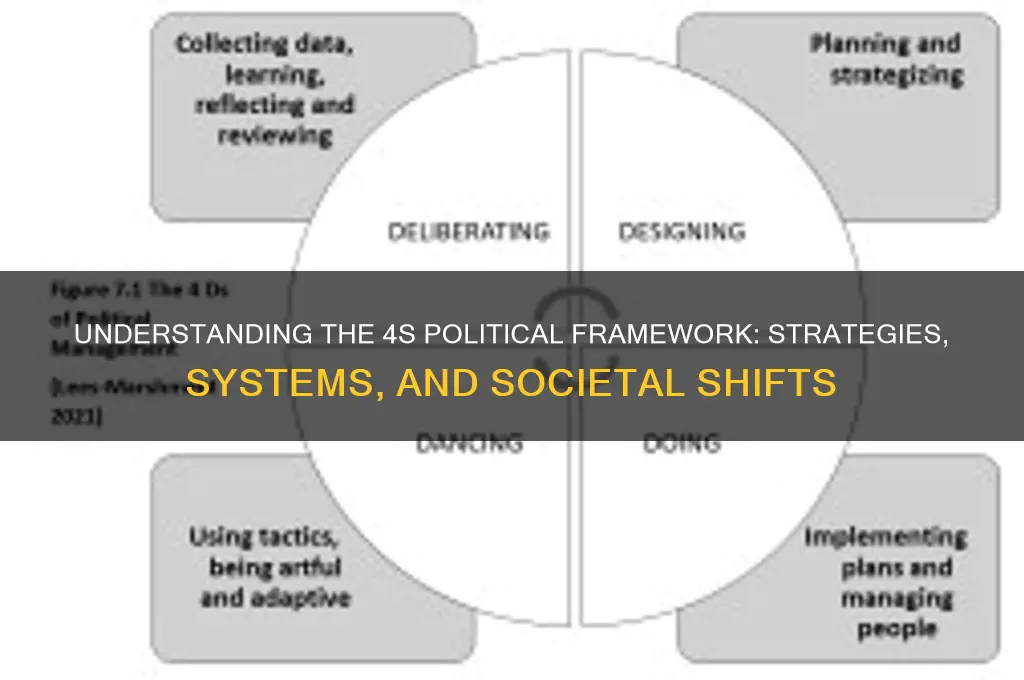

The term 4S political refers to a framework that integrates insights from Science and Technology Studies (STS) to analyze political phenomena, emphasizing four key elements: Society, Science, Technology, and the Environment. Rooted in the interdisciplinary approach of STS, 4S political examines how these components interact to shape political systems, policies, and power dynamics. It highlights the interconnectedness of scientific knowledge, technological advancements, societal values, and environmental impacts in political decision-making. By adopting this lens, scholars and practitioners can better understand how political agendas are influenced by scientific expertise, technological innovations, and environmental concerns, while also considering the broader societal implications. This approach challenges traditional political analysis by bringing attention to the often-overlooked role of science and technology in shaping governance, public policy, and global politics.

Explore related products

$16.95

$11.49 $19.99

What You'll Learn

- S Framework Overview: Science, technology, society, and environment interactions in political decision-making processes

- Policy Implications: How 4S influences policy formulation, implementation, and governance structures globally

- Ethical Considerations: Addressing ethical dilemmas arising from 4S in political and societal contexts

- Global Case Studies: Examining 4S political applications in diverse countries and regions worldwide

- Future Trends: Predicting the evolving role of 4S in shaping future political landscapes

4S Framework Overview: Science, technology, society, and environment interactions in political decision-making processes

Political decisions are increasingly shaped by the complex interplay of science, technology, society, and the environment—a dynamic captured by the 4S Framework. This framework serves as a lens to analyze how these elements influence policy-making, ensuring decisions are holistic and forward-thinking. For instance, climate policy cannot be crafted in isolation; it requires integrating scientific data on carbon emissions, technological solutions like renewable energy, societal acceptance of green practices, and environmental impact assessments.

Consider the rollout of electric vehicles (EVs) as a case study. Governments must balance scientific evidence on emissions reduction (e.g., EVs produce 50% less CO2 over their lifecycle compared to gasoline cars) with technological readiness (charging infrastructure availability), societal factors (consumer affordability and behavioral shifts), and environmental considerations (battery disposal and resource extraction). The 4S Framework highlights that neglecting any one of these dimensions—say, societal resistance due to high EV costs—can derail even the most scientifically sound policy.

To apply the 4S Framework effectively, decision-makers should follow a structured approach. First, identify the scientific baseline—what data or research underpins the issue? Second, assess technological feasibility—are the tools or innovations available and scalable? Third, gauge societal implications—how will communities be affected, and what are their priorities? Finally, evaluate environmental consequences—both immediate and long-term. For example, a policy to reduce plastic waste must consider scientific studies on microplastics, recycling technologies, public willingness to adopt reusable products, and the ecological impact of production alternatives.

A critical caution when using the 4S Framework is avoiding oversimplification. Each "S" interacts dynamically, and trade-offs are inevitable. For instance, a policy favoring rapid technological deployment (e.g., AI in healthcare) might outpace societal readiness or environmental safeguards. Policymakers must navigate these tensions by fostering interdisciplinary dialogue—engaging scientists, technologists, community leaders, and environmentalists in collaborative decision-making.

In conclusion, the 4S Framework is not just a theoretical tool but a practical guide for crafting resilient policies. By systematically addressing science, technology, society, and environment, it ensures decisions are informed, inclusive, and sustainable. Whether addressing public health crises, energy transitions, or urban planning, this framework empowers leaders to anticipate challenges and harness opportunities at the intersection of these critical domains.

Gracefully Declining Meetings: Polite Strategies to Say No Professionally

You may want to see also

Policy Implications: How 4S influences policy formulation, implementation, and governance structures globally

The 4S framework—Smart, Sustainable, Strategic, and Scalable—has emerged as a transformative lens for policy formulation, reshaping how governments and organizations approach global challenges. By prioritizing data-driven decision-making (Smart), long-term environmental and social viability (Sustainable), goal-aligned resource allocation (Strategic), and adaptable, replicable solutions (Scalable), 4S principles demand a paradigm shift in policy design. For instance, the European Green Deal integrates 4S by leveraging AI to monitor carbon emissions (Smart), ensuring renewable energy targets align with 2050 climate neutrality goals (Sustainable), coordinating cross-sector investments (Strategic), and piloting regional projects scalable to EU-wide implementation (Scalable). This example underscores how 4S compels policymakers to move beyond siloed, short-term interventions toward holistic, future-proof strategies.

However, embedding 4S into policy implementation reveals practical challenges. Scalability, for example, often clashes with local contexts, as evidenced by India’s Smart Cities Mission. While the initiative aimed to deploy IoT-enabled infrastructure (Smart) and reduce urban carbon footprints (Sustainable), its one-size-fits-all approach overlooked diverse municipal capacities, leading to uneven adoption. This highlights a critical caution: 4S implementation requires localized adaptation, not just technological or financial scaling. Policymakers must balance global ambitions with granular, context-specific adjustments, ensuring that "Scalable" does not become synonymous with "uniform."

Governance structures themselves must evolve to accommodate 4S principles, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and accountability. Traditional bureaucratic silos hinder the Strategic component of 4S, which demands cross-sector synergy. For instance, Singapore’s Whole-of-Government approach to water management integrates Smart sensors for leak detection, Sustainable desalination technologies, and Strategic pricing policies, all overseen by a unified agency. This model illustrates how governance must shift from hierarchical to networked, with clear metrics for measuring Smart outcomes (e.g., 20% water loss reduction) and Sustainable impacts (e.g., 30% renewable energy in desalination). Without such structural reforms, even the most innovative policies risk fragmentation and inefficiency.

Persuasively, the 4S framework also redefines policy evaluation, emphasizing long-term impact over short-term gains. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) initiatives, for instance, are increasingly assessed through 4S lenses: Are digital health platforms (Smart) reducing maternal mortality in rural Africa (Sustainable) while being cost-effective (Strategic) and replicable across regions (Scalable)? This shift necessitates new metrics, such as the "Sustainability Index" used by the World Bank to quantify policy resilience. By holding policies to 4S standards, governments can avoid the pitfalls of technocratic solutions that prioritize innovation without addressing equity or longevity.

In conclusion, 4S is not merely a checklist but a dynamic framework demanding proactive governance. Policymakers must embrace its interconnectedness—for example, ensuring Smart technologies serve Sustainable goals, not corporate interests. Practical tips include: (1) Conducting 4S audits during policy design to identify trade-offs (e.g., between Scalability and local relevance); (2) Establishing 4S task forces to bridge sectoral divides; and (3) Mandating 5-year impact assessments aligned with Sustainable targets. As global challenges grow more complex, 4S offers not just a roadmap, but a compass for policies that are as adaptable as they are ambitious.

Understanding NPA: Its Role and Impact in Political Landscapes

You may want to see also

Ethical Considerations: Addressing ethical dilemmas arising from 4S in political and societal contexts

The integration of 4S (Smart, Sustainable, Secure, and Scalable) technologies into political and societal frameworks has revolutionized governance, but it has also introduced complex ethical dilemmas. As these systems become more pervasive, questions arise about their impact on individual rights, societal equity, and democratic processes. For instance, smart surveillance systems, while enhancing security, often blur the lines between public safety and privacy invasion. Addressing these dilemmas requires a nuanced approach that balances innovation with ethical responsibility.

Consider the deployment of facial recognition technology in public spaces. While it can aid in crime prevention, its use raises concerns about consent, data misuse, and bias. Studies have shown that certain algorithms exhibit higher error rates for marginalized groups, perpetuating systemic inequalities. Policymakers must establish clear guidelines on data collection, storage, and usage, ensuring transparency and accountability. For example, implementing a "sunset clause" for data retention can limit the potential for abuse, while regular audits of algorithms can mitigate bias.

Another ethical challenge arises from the scalability of 4S technologies. As these systems expand, they often centralize power in the hands of a few entities, whether governments or corporations. This concentration of control can undermine democratic principles, as decisions affecting millions are made by a select few. To counteract this, decentralized governance models should be explored, such as blockchain-based voting systems that ensure transparency and citizen participation. However, such solutions must be carefully designed to prevent manipulation and ensure accessibility for all demographics.

In the realm of sustainability, 4S technologies promise to address environmental challenges, but their implementation often involves trade-offs. For instance, the production of smart devices relies on rare earth minerals, whose extraction can harm ecosystems and exploit labor. Ethical considerations demand a holistic approach, integrating lifecycle assessments and fair trade practices into the development and deployment of these technologies. Governments and corporations must prioritize long-term sustainability over short-term gains, fostering innovation that benefits both people and the planet.

Ultimately, addressing ethical dilemmas in 4S political contexts requires a proactive, interdisciplinary approach. Stakeholders must engage in ongoing dialogue, involving technologists, ethicists, policymakers, and the public. By fostering a culture of ethical awareness and accountability, societies can harness the potential of 4S technologies while safeguarding fundamental values. Practical steps include creating independent oversight bodies, investing in ethical AI research, and educating citizens about their rights and responsibilities in a technologically mediated world. The goal is not to stifle innovation but to ensure it serves the greater good, equitably and justly.

Understanding Political Efficacy: Empowering Citizens in Democratic Engagement

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Global Case Studies: Examining 4S political applications in diverse countries and regions worldwide

The 4S political framework—Security, Sustainability, Solidarity, and Sovereignty—has emerged as a versatile tool for analyzing governance strategies across diverse geopolitical contexts. By examining its application globally, we can uncover how nations prioritize these pillars to address unique challenges. For instance, in Scandinavia, Solidarity takes center stage through robust welfare systems, while in the Middle East, Security often dominates due to regional instability. These variations highlight the framework’s adaptability and its capacity to reflect local realities.

Consider the case of Costa Rica, a nation that has seamlessly integrated Sustainability into its political DNA. With over 98% of its electricity derived from renewable sources, the country exemplifies how environmental stewardship can align with economic growth. Here, the 4S framework isn’t just a theoretical construct but a practical blueprint for policy-making. Policymakers in developing nations can draw lessons from Costa Rica’s success by prioritizing renewable energy investments and eco-tourism, ensuring long-term ecological and economic resilience.

In contrast, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) offers a complex interplay of Sovereignty and Sustainability. While the BRI enhances China’s global influence, it also raises concerns about environmental degradation in participating countries. This case study underscores the tension between national ambition and global responsibility. For nations engaging in similar initiatives, a balanced approach—such as incorporating green infrastructure standards—can mitigate risks while advancing shared prosperity.

Africa’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates the role of Solidarity in crisis management. Countries like Rwanda and Senegal leveraged regional cooperation and community-driven initiatives to curb the virus’s spread. Their strategies demonstrate how Solidarity, when paired with Security measures, can yield effective outcomes even in resource-constrained settings. Policymakers in other regions can emulate this model by fostering cross-border collaboration and empowering local communities.

Finally, the European Union’s Green Deal provides a compelling example of integrating all four pillars into a cohesive policy framework. By linking Security (energy independence), Sustainability (carbon neutrality), Solidarity (just transition funds), and Sovereignty (strategic autonomy), the EU aims to redefine global leadership in climate action. This holistic approach serves as a roadmap for other blocs seeking to address multifaceted challenges. For instance, ASEAN nations could adapt this model to tackle shared issues like maritime security and environmental degradation.

In each of these cases, the 4S framework reveals its utility as both a diagnostic tool and a strategic guide. By studying these global applications, policymakers can tailor their approaches to local contexts, ensuring that Security, Sustainability, Solidarity, and Sovereignty are not just abstract ideals but actionable principles driving progress.

Mastering the Art of Polite Rescheduling: Tips for Graceful Communication

You may want to see also

Future Trends: Predicting the evolving role of 4S in shaping future political landscapes

The 4S political framework—security, sustainability, solidarity, and sovereignty—is increasingly becoming the lens through which future political landscapes will be shaped. As global challenges like climate change, technological disruption, and shifting power dynamics intensify, these four pillars will not only define policy agendas but also dictate how nations and communities interact. For instance, sustainability is no longer a peripheral concern but a central driver of economic and foreign policy, with countries like the EU embedding it into their Green Deal and China committing to carbon neutrality by 2060. This shift underscores how 4S principles are evolving from theoretical ideals to actionable imperatives.

Consider the interplay between security and sovereignty in the digital age. As cyber threats escalate and artificial intelligence reshapes warfare, nations are reevaluating what it means to protect their interests. Traditional notions of sovereignty are being challenged by the borderless nature of technology, forcing governments to collaborate on global standards while fiercely guarding their digital autonomy. For example, the U.S. and China’s tech decoupling reflects a broader struggle to balance security with sovereignty in a multipolar world. Policymakers must navigate this tension, ensuring that technological advancements do not undermine national integrity or global stability.

Solidarity, often overlooked in geopolitical discourse, will emerge as a critical counterbalance to rising nationalism and inequality. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the fragility of global cooperation, but it also demonstrated the power of collective action. Future political landscapes will likely see a resurgence of regional alliances and multilateral frameworks designed to foster solidarity, particularly in addressing shared threats like pandemics, migration crises, and resource scarcity. For instance, the African Union’s Agenda 2063 emphasizes unity and shared prosperity as foundational principles for the continent’s future.

To predict the evolving role of 4S, consider this three-step approach: first, map the intersections of these principles in current policies. For example, how do sustainability initiatives impact national security strategies? Second, analyze emerging technologies and their potential to disrupt or reinforce 4S frameworks. Quantum computing, for instance, could revolutionize encryption, reshaping the security-sovereignty dynamic. Finally, assess public sentiment and demographic shifts, as younger generations increasingly prioritize sustainability and solidarity over traditional sovereignty.

A cautionary note: overemphasizing one pillar at the expense of others could lead to unintended consequences. For instance, prioritizing sovereignty in climate negotiations could hinder global sustainability efforts. Policymakers must adopt a holistic approach, recognizing that the 4S framework is interdependent. Practical tips include fostering cross-sector collaborations, investing in education to build awareness, and leveraging data analytics to track progress. By doing so, nations can ensure that 4S principles not only shape but also stabilize future political landscapes.

Cleopatra's Legacy: Politics, Power, and Her Enduring Historical Influence

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

"4S Political" typically refers to the intersection of Science, Technology, and Society (STS) studies with a focus on Social, Scientific, Sociological, and Political dimensions. It emphasizes how political systems, policies, and power dynamics influence and are influenced by scientific and technological advancements.

Unlike traditional political science, which often focuses on institutions, governance, and policy-making, 4S Political incorporates insights from STS to examine the role of science, technology, and expertise in shaping political outcomes, public discourse, and societal norms. It is more interdisciplinary and critically examines the interplay between knowledge, power, and politics.

Examples include the politics of climate change and environmental science, the role of technology in surveillance and governance, the influence of scientific expertise in policy-making, and the societal implications of emerging technologies like AI or biotechnology. These topics explore how science and technology are embedded in political processes and power structures.