Bond politics refers to the strategic use of financial instruments, particularly municipal bonds, to influence political outcomes and shape public policy. In this context, bonds are not merely tools for raising capital but also mechanisms through which governments, interest groups, and investors can exert leverage over political decisions. For instance, the issuance or withholding of bonds can be used to fund or block specific projects, such as infrastructure development or social programs, thereby aligning financial interests with political agendas. This intersection of finance and politics highlights how bond markets can become arenas for power struggles, where stakeholders negotiate, lobby, and maneuver to advance their objectives. Understanding bond politics requires examining the relationships between governments, investors, and the public, as well as the broader implications for democracy, accountability, and economic equity.

Explore related products

$21.97 $27.95

What You'll Learn

- Bond Issuance and Government Borrowing: How governments issue bonds to fund projects and manage debt

- Bond Markets and Investor Influence: Role of bond markets in shaping fiscal and monetary policies

- Sovereign Debt Crises: Political consequences of high debt levels and default risks

- Bond Ratings and Political Trust: Impact of credit ratings on government credibility and borrowing costs

- Bonds as Political Tools: Use of bonds to achieve political goals, like infrastructure or stimulus

Bond Issuance and Government Borrowing: How governments issue bonds to fund projects and manage debt

Governments, like households and businesses, often need to borrow money to fund essential projects—building roads, schools, or responding to crises. Unlike swiping a credit card, they issue bonds, a sophisticated tool for raising capital while managing long-term debt. This process, known as bond issuance, is a cornerstone of public finance, blending economic strategy with political pragmatism.

Consider a city planning to construct a new hospital. Instead of taxing residents heavily upfront, the government issues municipal bonds. These bonds are essentially IOUs, promising investors regular interest payments and the return of their principal at maturity. Investors, ranging from individual savers to institutional funds, buy these bonds, providing the city with immediate cash. The hospital gets built, and the government repays the debt over time, often decades. This approach spreads the financial burden across generations, ensuring that current taxpayers aren’t overwhelmed while future beneficiaries contribute through interest payments.

However, bond issuance isn’t without risks or political implications. High debt levels can lead to credit downgrades, increasing borrowing costs and limiting future flexibility. For instance, Greece’s bond yields soared during its debt crisis, reflecting investor skepticism about repayment. Governments must balance the need for funding with fiscal responsibility, often navigating political pressures to spend versus the economic imperative to maintain creditworthiness. Transparency in how bond proceeds are used is critical; misallocation of funds can erode public trust and investor confidence.

To manage these challenges, governments employ strategies like issuing bonds in tranches, diversifying investor bases, and aligning bond maturities with project timelines. For example, a 30-year bond might fund infrastructure with a similar lifespan, ensuring revenue from the asset helps service the debt. Additionally, governments may use bond proceeds to refinance existing debt at lower rates, a tactic akin to refinancing a mortgage. This requires astute timing and market analysis, as interest rate fluctuations can significantly impact costs.

In essence, bond issuance is both a financial mechanism and a political act. It reflects a government’s ability to plan for the future, manage resources, and maintain credibility. When executed wisely, it funds progress without burdening any single generation. When mishandled, it becomes a liability, constraining growth and eroding trust. Understanding this dynamic is key to appreciating the role of bonds in shaping public policy and economic stability.

Is Morocco Politically Stable? Analyzing Its Governance and Security Landscape

You may want to see also

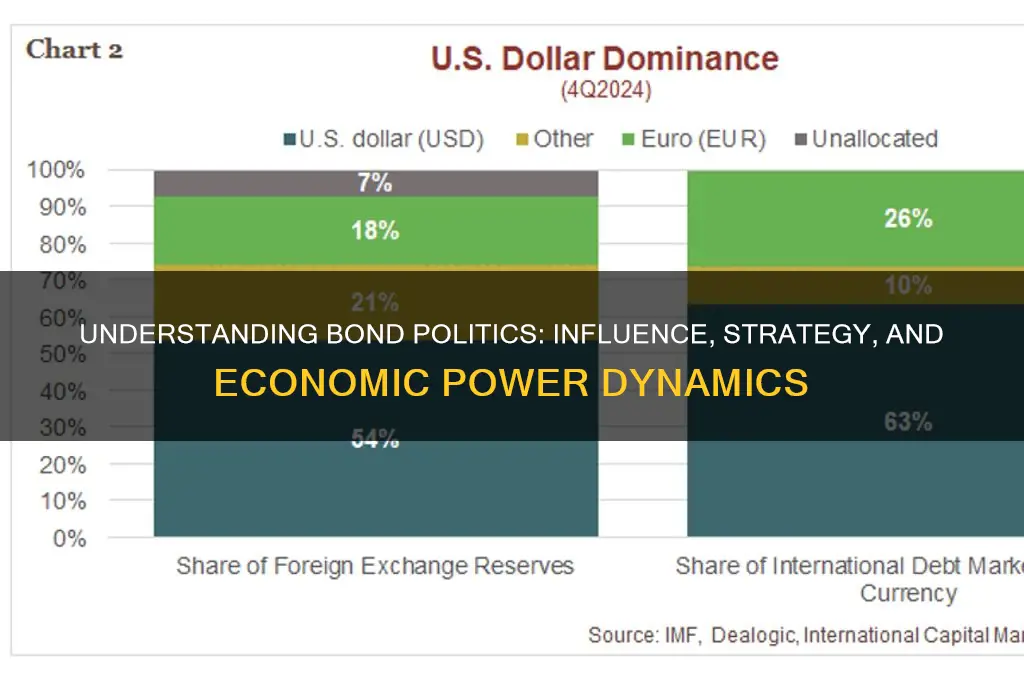

Bond Markets and Investor Influence: Role of bond markets in shaping fiscal and monetary policies

Bond markets are the silent architects of fiscal and monetary policies, wielding influence through the collective decisions of investors. When governments issue bonds to finance deficits or fund projects, they effectively borrow from a global pool of capital. Investors, ranging from pension funds to sovereign wealth funds, dictate the terms of this borrowing by demanding yields that reflect their assessment of risk. A government with high debt levels or unstable policies faces higher borrowing costs, forcing it to either adjust spending or risk fiscal insolvency. This dynamic creates a feedback loop: bond markets reward prudent policies with lower yields and punish recklessness with higher ones, shaping government behavior in real time.

Consider the European sovereign debt crisis of 2010–2012. Countries like Greece and Italy saw their bond yields spike as investors lost confidence in their ability to repay debt. This market pressure compelled these nations to implement austerity measures and structural reforms, effectively surrendering fiscal autonomy to regain investor trust. Conversely, Germany, perceived as a safe haven, enjoyed record-low borrowing costs, enabling it to invest in infrastructure and social programs. This example illustrates how bond markets act as a disciplining force, aligning fiscal policies with investor expectations, often at the expense of domestic political priorities.

The influence of bond markets extends beyond fiscal policy to monetary policy as well. Central banks, tasked with maintaining price stability and economic growth, must navigate the expectations of bond investors. For instance, when the U.S. Federal Reserve signals a shift in interest rates, bond yields adjust accordingly, impacting borrowing costs across the economy. Investors who anticipate inflation may demand higher yields, forcing central banks to tighten policy to stabilize markets. This interplay highlights how bond markets constrain monetary policy, limiting the ability of central banks to act independently of investor sentiment.

To navigate this landscape, policymakers must balance domestic goals with market demands. A practical tip for governments is to maintain transparent fiscal frameworks and credible monetary policies, reducing uncertainty for investors. For instance, countries with independent fiscal councils or inflation-targeting regimes often enjoy lower borrowing costs. Conversely, erratic policy changes or opaque financial reporting can trigger market volatility, as seen in Turkey’s 2018 currency crisis. By understanding the mechanics of bond markets, policymakers can mitigate risks and harness investor influence to achieve sustainable economic outcomes.

Ultimately, the role of bond markets in shaping fiscal and monetary policies underscores the globalization of capital and the interdependence of economies. Investors, driven by profit motives, act as both financiers and arbiters of government behavior. While this dynamic can promote fiscal discipline, it also raises questions about democratic accountability when market pressures override public interests. As bond markets continue to evolve, the challenge for policymakers lies in striking a balance between responding to investor demands and pursuing policies that serve the broader welfare of their citizens.

Does Political Texting Work? Analyzing Its Impact on Voter Engagement

You may want to see also

Sovereign Debt Crises: Political consequences of high debt levels and default risks

High levels of sovereign debt can trigger political crises that reshape governments, economies, and societies. When a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio surpasses 75%, historical data shows a heightened risk of default, austerity measures, and political instability. Greece’s 2010 debt crisis, for instance, led to the collapse of its ruling party, the rise of anti-austerity movements like Syriza, and prolonged social unrest. Such scenarios illustrate how fiscal irresponsibility becomes a political liability, as citizens lose trust in institutions that fail to manage public finances sustainably.

The political consequences of default risks extend beyond domestic turmoil. Internationally, creditors and investors lose confidence, triggering capital flight and currency devaluation. Argentina’s 2001 default, the largest in history at $100 billion, isolated the country from global markets for over a decade and forced successive governments to adopt populist policies to regain public support. This cycle of default, isolation, and populism underscores how sovereign debt crises erode a nation’s credibility, limiting its ability to secure future financing or negotiate favorable trade agreements.

Austerity measures, often imposed as a condition for bailout packages, become political lightning rods. Cutting public spending on healthcare, education, and pensions alienates voters, particularly the middle and lower classes. In Spain, austerity policies implemented after the 2012 debt crisis fueled the rise of Podemos, a left-wing party opposing fiscal conservatism. Conversely, governments that resist austerity risk further downgrades in credit ratings, creating a no-win scenario where political survival hinges on balancing fiscal discipline with social welfare.

Proactive debt management can mitigate these risks. Countries like Estonia and Chile have maintained debt-to-GDP ratios below 20% through prudent fiscal policies, insulating themselves from political fallout. For nations already in crisis, restructuring debt with extended repayment periods or lower interest rates can provide breathing room. However, such measures require political will and transparency, as seen in Ecuador’s 2020 debt renegotiation, which avoided default by engaging creditors early. The takeaway is clear: managing sovereign debt is not just an economic imperative but a political survival strategy.

Understanding Mutability Politics: Shifting Identities, Power Dynamics, and Social Change

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Bond Ratings and Political Trust: Impact of credit ratings on government credibility and borrowing costs

Credit ratings are the financial world’s report card for governments, and their impact extends far beyond Wall Street. A downgrade from AAA to AA+ isn’t just a number change—it’s a public declaration of diminished trust. For instance, when Standard & Poor’s downgraded U.S. sovereign debt in 2011, it wasn’t just about fiscal policy; it signaled a perceived erosion of political stability and bipartisan cooperation. This single event rippled through markets, raising borrowing costs and forcing policymakers to address not just deficits, but the credibility of their governance.

Consider the mechanics: bond ratings directly influence the interest rates governments pay on their debt. A country with a higher rating can borrow at lower costs, freeing up resources for public services or infrastructure. Conversely, a downgrade can trigger a vicious cycle. Investors demand higher yields to offset perceived risk, which increases debt servicing costs, leaving fewer funds for essential programs. This financial strain often translates into political pressure, as citizens question a government’s ability to manage both the economy and their trust.

To mitigate this, governments must navigate a delicate balance. First, transparency is key. Regular, detailed fiscal reporting reassures rating agencies and investors alike. Second, structural reforms—such as pension overhauls or tax system modernization—demonstrate long-term fiscal responsibility. Third, political stability matters. Frequent leadership changes or policy reversals can signal unpredictability, prompting downgrades. For example, countries with coalition governments often face scrutiny if their alliances appear fragile.

However, there’s a cautionary note: over-reliance on ratings can lead to short-termism. Governments might prioritize quick fiscal fixes over sustainable policies to avoid downgrades, sacrificing long-term growth for immediate relief. This trade-off highlights the need for a nuanced approach—one that balances market expectations with genuine economic and political reform.

Ultimately, bond ratings are more than financial metrics; they’re a reflection of political trust. A government’s ability to maintain a high rating isn’t just about fiscal discipline—it’s about demonstrating consistent, credible leadership. For policymakers, the takeaway is clear: economic management and political trust are two sides of the same coin. Ignore one, and the other will suffer—along with the nation’s borrowing costs.

Understanding Political Settlements: Key Concepts and Real-World Applications

You may want to see also

Bonds as Political Tools: Use of bonds to achieve political goals, like infrastructure or stimulus

Governments worldwide increasingly leverage bonds as strategic instruments to advance political agendas, particularly in infrastructure development and economic stimulus. By issuing bonds, they secure funding for large-scale projects without immediate tax increases, a politically palatable approach. For instance, the U.S. Treasury’s issuance of municipal bonds has historically financed highways, bridges, and schools, aligning with political promises to improve public services. This method allows leaders to claim credit for progress while deferring fiscal burden, making bonds a dual-purpose tool: funding and political capital.

Consider the analytical perspective: bonds enable targeted investment in politically prioritized sectors. During economic downturns, stimulus bonds inject liquidity into markets, as seen in the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Such bonds not only create jobs but also signal governmental responsiveness to crises, bolstering public approval. However, this strategy carries risks. Over-reliance on bond financing can lead to debt accumulation, as evident in countries like Greece, where excessive borrowing precipitated a fiscal crisis. Balancing ambition with sustainability is critical for long-term success.

From an instructive standpoint, policymakers must navigate bond issuance with precision. First, identify high-impact projects with clear public benefits, such as renewable energy initiatives or urban transit systems. Second, structure bonds with competitive interest rates to attract investors while ensuring affordability. Third, communicate transparently to maintain public trust, detailing how funds will address specific needs. For example, California’s Proposition 1 in 2014 explicitly tied water infrastructure bonds to drought mitigation, garnering voter support.

Persuasively, bonds democratize investment by allowing citizens to contribute to national development. Retail bonds, marketed directly to individuals, foster a sense of ownership in public projects. In the UK, “War Bonds” during World War II not only funded the war effort but also united the populace behind a common cause. Modern equivalents, like green bonds for climate initiatives, similarly align financial participation with political priorities, turning investors into stakeholders in policy outcomes.

Comparatively, bonds offer advantages over alternative funding methods. Unlike taxation, they avoid immediate public backlash. Unlike privatization, they retain governmental control over assets. Yet, they require disciplined management to avoid pitfalls like default or misallocation. For instance, China’s local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) have faced scrutiny for using bonds to fund low-return projects, underscoring the need for rigorous oversight.

In conclusion, bonds are a versatile political tool, capable of driving infrastructure growth and economic recovery while shaping public perception. Their effectiveness hinges on strategic planning, transparency, and fiscal responsibility. When wielded thoughtfully, bonds not only achieve political goals but also build a foundation for sustainable progress.

Understanding the Core: What is a Political Basic Narrative?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In politics, a bond often refers to a financial instrument issued by governments to raise capital for public projects, such as infrastructure, education, or healthcare. Voters may approve these bonds through referendums, and they are repaid with taxpayer funds over time.

Political bonds, or municipal bonds, are issued by governments and often offer tax advantages, while corporate bonds are issued by companies to raise capital for business operations. Political bonds are typically backed by taxpayer funds, whereas corporate bonds rely on the company’s revenue.

In some contexts, "bond" may refer to the connection or trust between politicians and voters. However, in financial terms, bonds can be a campaign issue when politicians propose or oppose bond measures to fund specific projects, influencing voter decisions.

Political bonds are generally considered low-risk because they are backed by government revenue. However, if a government mismanages funds or faces financial difficulties, taxpayers may bear the burden of higher taxes or reduced services to repay the bonds.

Voters often have a direct say in bond politics through ballot measures or referendums. By voting on bond proposals, citizens decide whether to approve funding for public projects, making them key participants in the political and financial process.