Political behavior is shaped by a complex interplay of individual, societal, and structural factors. At the individual level, personal characteristics such as age, gender, education, and socioeconomic status significantly influence political attitudes and actions. Societal factors, including cultural norms, religious beliefs, and community values, play a crucial role in molding political preferences and participation. Structural elements, such as the political system, electoral processes, and the presence of institutions like political parties and interest groups, further determine how individuals engage with politics. Additionally, external influences like media, globalization, and historical events can reshape political behavior by altering perceptions and priorities. Understanding these factors collectively provides insight into why people act politically in the ways they do.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Socioeconomic Status: Income, education, occupation influence political views, participation, and voting behavior significantly

- Cultural Identity: Ethnicity, religion, and traditions shape political beliefs and affiliations strongly

- Media Influence: News, social media, and propaganda impact public opinion and political choices

- Generational Differences: Age groups vary in political priorities, values, and engagement levels

- Geographic Location: Urban, rural, or regional contexts affect political attitudes and behaviors

Socioeconomic Status: Income, education, occupation influence political views, participation, and voting behavior significantly

Socioeconomic status (SES) acts as a prism, refracting political behavior into distinct patterns. Higher income often correlates with conservative leanings, as financial stability fosters a preference for maintaining existing systems. Conversely, lower-income individuals may gravitate toward progressive policies promising redistribution and social safety nets. This isn't a hard rule; exceptions abound, but the trend is statistically significant. For instance, a 2020 Pew Research study found that 52% of Americans earning over $100,000 annually identified as Republican or leaned Republican, compared to 36% of those earning under $30,000.

Understanding this income-ideology link is crucial for predicting voting patterns and crafting effective political strategies.

Education, another pillar of SES, shapes political engagement in nuanced ways. Higher educational attainment generally correlates with increased political participation, from voting to contacting representatives. Educated individuals are more likely to possess the critical thinking skills and civic knowledge necessary for informed political action. However, education doesn't dictate political ideology as strongly as income. A college graduate from a working-class background might lean left due to their personal experiences, while a wealthy graduate could embrace conservative values. The key takeaway: education amplifies political engagement, but its influence on specific views is mediated by other factors.

Consider this: encouraging political education initiatives in underserved communities could empower individuals to participate more actively, regardless of their income level.

Occupation, the third leg of the SES stool, further complicates the picture. Blue-collar workers, often facing economic insecurity, may prioritize policies benefiting labor rights and social welfare. White-collar professionals, conversely, might favor policies promoting economic growth and individual initiative. However, occupational culture also plays a role. Teachers, for example, tend to lean left due to their exposure to social issues and commitment to public service, while business owners might lean right due to their focus on profit and individual enterprise. Analyzing occupational groups provides valuable insights into the specific concerns driving political behavior within different socioeconomic strata.

The interplay of income, education, and occupation within SES creates a complex tapestry of political behavior. Recognizing these influences allows us to move beyond simplistic stereotypes and understand the diverse motivations behind political choices. By acknowledging the impact of SES, we can foster more inclusive political discourse, address systemic inequalities, and build a more representative democracy.

Exploring the Mechanics and Functionality of Jet Polishing Techniques

You may want to see also

Cultural Identity: Ethnicity, religion, and traditions shape political beliefs and affiliations strongly

Cultural identity, rooted in ethnicity, religion, and traditions, profoundly molds political behavior by framing how individuals perceive societal issues and align with political ideologies. For instance, in the United States, African American voters often prioritize candidates who address systemic racism and economic inequality, reflecting a collective historical experience of discrimination. Similarly, in India, caste identity influences voting patterns, with lower-caste communities supporting parties advocating for social justice and affirmative action. These examples illustrate how cultural identity acts as a lens through which political priorities are defined, often overriding other factors like socioeconomic status or education.

To understand this dynamic, consider the role of religion in shaping political affiliations. In countries like Poland, the Catholic Church’s influence is evident in the widespread support for conservative policies on abortion and LGBTQ+ rights. Conversely, in secular nations like Sweden, religious identity plays a minimal role in political behavior, with social democratic values dominating. This contrast highlights how the salience of religious identity varies across contexts, yet where present, it can be a decisive factor in political decision-making. For practical application, political campaigns targeting religious communities should tailor messages to align with specific doctrinal values, avoiding generic appeals.

Traditions, often intertwined with ethnicity, further reinforce political loyalties. In Scotland, the Scottish National Party (SNP) leverages cultural symbols like the tartan and Gaelic language to rally support for independence. This strategy taps into a shared heritage, fostering a sense of unity and purpose among voters. Similarly, in Mexico, indigenous communities often back parties that promise to protect their land rights and cultural autonomy. To engage such groups effectively, policymakers must demonstrate respect for and understanding of these traditions, rather than viewing them as obstacles to modernization.

However, the influence of cultural identity is not without challenges. In diverse societies, competing cultural narratives can lead to polarization. For example, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, ethnic divisions between Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats have historically fueled political conflict, with each group aligning with parties that prioritize their specific interests. To mitigate this, inclusive policies that acknowledge and celebrate cultural diversity while fostering common national goals are essential. A practical tip for leaders is to create platforms where diverse cultural voices can be heard, reducing the risk of marginalization and alienation.

In conclusion, cultural identity serves as a powerful determinant of political behavior, with ethnicity, religion, and traditions shaping beliefs and affiliations in distinct ways. By recognizing and addressing these factors, politicians, activists, and policymakers can build more inclusive and responsive political systems. For individuals, understanding how cultural identity influences political choices can foster empathy and dialogue across divides, ultimately strengthening democratic participation.

Does Politico Lean Left? Analyzing Its Editorial Stance and Bias

You may want to see also

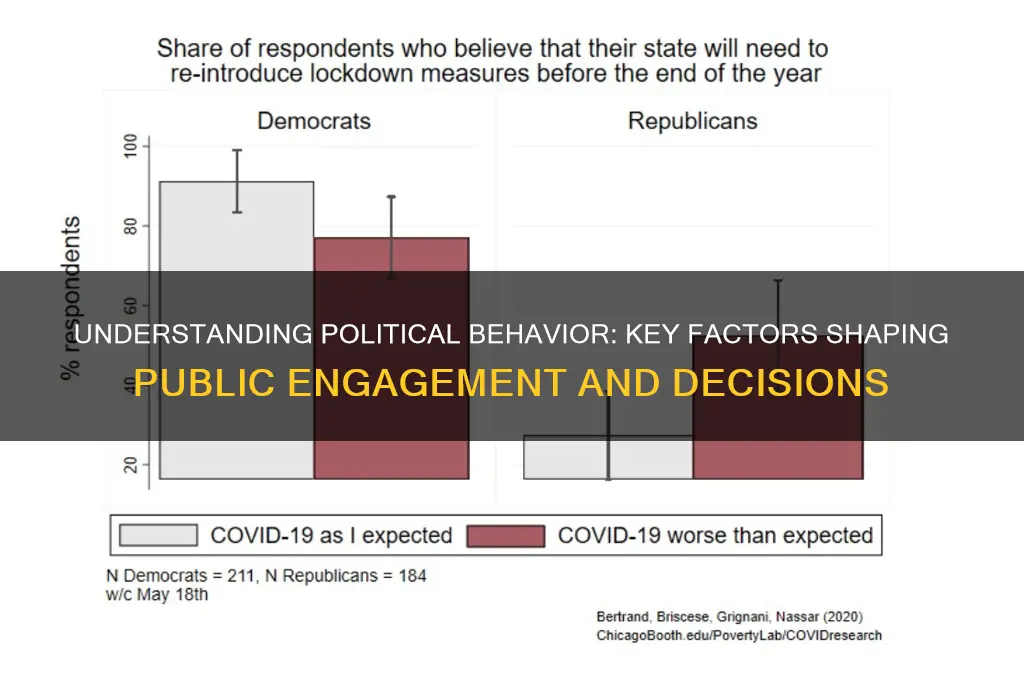

Media Influence: News, social media, and propaganda impact public opinion and political choices

Media consumption shapes political behavior more profoundly than ever, with news outlets, social platforms, and propaganda campaigns acting as architects of public opinion. Consider the 2016 U.S. presidential election, where Cambridge Analytica exploited Facebook data to micro-target voters with tailored political ads, swaying undecided demographics. This example underscores how media isn't just a reflector of political sentiment but an active manipulator of it. The algorithms driving social media amplify polarizing content, creating echo chambers that reinforce existing beliefs while excluding opposing viewpoints. News outlets, whether biased or balanced, frame issues in ways that influence how audiences perceive political candidates, policies, and events. Propaganda, often disguised as legitimate information, further muddies the waters, making it difficult for individuals to discern fact from fiction. Together, these forces create a media landscape that doesn’t just inform but directs political behavior.

To understand media’s role, dissect its mechanisms. News outlets employ framing techniques—emphasizing specific aspects of a story to shape its interpretation. For instance, a headline about immigration might focus on economic benefits or security threats, steering public sentiment accordingly. Social media platforms leverage engagement metrics, prioritizing sensational or emotionally charged content that drives clicks and shares. This incentivizes the spread of misinformation, as falsehoods often outpace truth in virality. Propaganda operates through repetition and emotional appeals, bypassing rational thought to embed narratives deeply. A practical tip for navigating this terrain is to diversify your media diet: follow outlets with differing perspectives, fact-check suspicious claims, and limit time on social media algorithms that reinforce biases. By understanding these mechanisms, individuals can become more critical consumers of information, reducing media’s ability to manipulate their political choices.

The persuasive power of media lies in its ability to tap into emotions, often at the expense of rational decision-making. Political ads, for example, rarely focus on policy details; instead, they evoke fear, hope, or anger to sway voters. Social media takes this a step further by personalizing these appeals, using data to target individuals based on their vulnerabilities. Propaganda campaigns exploit historical grievances or national pride, framing political choices as matters of identity rather than policy. To counteract this, cultivate emotional awareness: recognize when a message triggers a strong reaction and pause to evaluate its substance. Another strategy is to engage in deliberate, fact-based discussions with others, which can help break the hold of emotionally charged narratives. By prioritizing reason over reaction, individuals can reclaim agency in their political decisions.

Comparing traditional news with social media highlights their distinct impacts on political behavior. Traditional news, despite its biases, often adheres to journalistic standards, providing context and verification. Social media, in contrast, thrives on immediacy and sensationalism, with little regard for accuracy. Propaganda blurs the line between the two, masquerading as news while pushing agendas. For instance, during the Brexit campaign, traditional news outlets debated economic implications, while social media flooded with emotive, often false, claims about immigration. This comparison reveals the importance of source literacy: verify the credibility of information, cross-reference claims, and question the intent behind messages. By distinguishing between news, noise, and manipulation, individuals can navigate media’s influence more effectively.

Ultimately, media’s impact on political behavior is a double-edged sword—it can inform and empower, but it can also mislead and manipulate. The key lies in active engagement rather than passive consumption. Start by setting boundaries: limit daily social media use to reduce exposure to algorithmic manipulation. Use tools like fact-checking websites (e.g., Snopes, PolitiFact) to verify information. Engage with diverse perspectives, even those that challenge your beliefs, to avoid echo chambers. Finally, educate others, especially younger audiences, on media literacy, as they are particularly vulnerable to online manipulation. By taking these steps, individuals can harness media’s potential while safeguarding their political autonomy. The goal isn’t to avoid media but to master it, ensuring it serves as a tool for enlightenment, not control.

Tactful Tips: How to Graciously Mention Your Wedding Registry

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Generational Differences: Age groups vary in political priorities, values, and engagement levels

Political behavior is not uniform across age groups. Younger generations, such as Millennials and Gen Z, often prioritize issues like climate change, social justice, and student debt, reflecting their immediate concerns and future-oriented outlook. In contrast, older generations, like Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation, tend to focus on economic stability, national security, and healthcare, shaped by their life experiences and proximity to retirement. These differing priorities are not just theoretical; they manifest in voting patterns, policy support, and activism. For instance, younger voters are more likely to back progressive candidates advocating for systemic change, while older voters often favor established figures promising continuity.

Consider the mechanics of generational engagement. Younger age groups are more likely to use digital platforms for political participation, from social media campaigns to online petitions. This tech-savvy approach contrasts with older generations, who may rely more on traditional methods like town hall meetings or print media. However, engagement levels vary too. While younger voters are often criticized for lower turnout rates, their participation spikes during elections featuring issues directly impacting their future, such as environmental policy or education reform. Conversely, older voters consistently turn out in higher numbers, driven by a sense of civic duty honed over decades.

To bridge generational divides, policymakers and activists must tailor their strategies. For younger audiences, framing issues in terms of long-term impact and leveraging digital tools can increase engagement. For example, a campaign highlighting how climate inaction will affect Millennials’ and Gen Z’s lifetimes could resonate deeply. For older generations, emphasizing stability and incremental progress might be more effective. Practical tips include intergenerational dialogues, where younger and older voters share perspectives, and targeted messaging that acknowledges each group’s unique concerns.

A comparative analysis reveals that generational differences are not static; they evolve as cohorts age and societal contexts shift. For instance, the Silent Generation, once known for its conservatism, now includes many who support progressive healthcare policies due to personal need. Similarly, Millennials, once labeled apathetic, are increasingly engaged as they enter positions of influence. This fluidity underscores the importance of ongoing research to understand how generational priorities adapt over time. By recognizing these dynamics, political actors can craft more inclusive and effective strategies.

Finally, generational differences offer a lens for predicting future political trends. As younger generations, who currently make up a growing share of the electorate, age into political prominence, their priorities will likely shape national agendas. Issues like sustainability, digital privacy, and economic inequality may dominate discourse. Conversely, as older generations decline in numbers, their influence on specific policies may wane. This shift necessitates proactive planning, such as educating younger voters on the historical context of current issues and encouraging older voters to mentor the next generation. Understanding these generational nuances is not just academic—it’s a practical roadmap for fostering a more cohesive and responsive political landscape.

Presidents' Strategies: Defending Political Rivals in Modern Democracy

You may want to see also

Geographic Location: Urban, rural, or regional contexts affect political attitudes and behaviors

Geographic location profoundly shapes political attitudes and behaviors, with urban, rural, and regional contexts each fostering distinct political cultures. Urban areas, characterized by high population density and diversity, often lean toward progressive policies. Cities like New York and San Francisco exemplify this trend, with residents prioritizing issues such as public transportation, affordable housing, and social equity. The anonymity and fast-paced nature of urban life can also foster individualism, leading to support for policies that emphasize personal freedoms and multiculturalism. In contrast, rural areas, with their lower population density and stronger sense of community, tend to favor conservative values. Residents in regions like the Midwest or the South often prioritize issues such as gun rights, traditional family values, and local control over government. The slower pace of rural life and reliance on agriculture or natural resources can also shape political priorities, such as opposition to environmental regulations perceived as harmful to local industries.

To understand these dynamics, consider the role of regional identity in shaping political behavior. In the United States, the South’s historical legacy of states’ rights and agrarian traditions continues to influence its political leanings, while the Northeast’s industrial history and urban centers align it with more progressive policies. Regional economies also play a critical role. For instance, coal-dependent regions in Appalachia may resist climate policies that threaten local jobs, while tech hubs in Silicon Valley advocate for innovation-friendly regulations. Practical tip: When analyzing political trends, map them against geographic and economic data to identify correlations. For example, compare voting patterns in counties with high agricultural employment versus those dominated by service industries.

A comparative analysis reveals how geographic location intersects with other factors, such as age and education. Urban young adults, often exposed to diverse perspectives through education and media, may embrace liberal ideologies, while rural youth, influenced by family and local traditions, might lean conservative. However, urbanization is not uniform in its effects. Smaller cities or suburban areas can exhibit hybrid political behaviors, blending rural conservatism with urban progressivism. Caution: Avoid oversimplifying these distinctions, as exceptions abound. For instance, college towns in rural areas can become pockets of liberalism, while gentrifying urban neighborhoods may shift toward more conservative views as demographics change.

Persuasive arguments often leverage geographic identity to mobilize voters. Political campaigns tailor messages to resonate with regional concerns—highlighting job creation in economically depressed areas or environmental protection in regions prone to natural disasters. For instance, a candidate in a drought-stricken region might emphasize water management policies, while one in a manufacturing hub might focus on trade agreements. Practical takeaway: When engaging in political discourse, acknowledge the geographic context of your audience to build credibility and relevance. For example, a policy proposal for renewable energy might emphasize job creation in rural areas rather than solely focusing on environmental benefits.

Finally, geographic location influences political participation rates and methods. Urban residents, with greater access to polling places and public transportation, often have higher voter turnout. Rural areas, however, may rely more on absentee ballots or early voting due to greater distances. Regional disparities in political infrastructure, such as the availability of community organizations or campaign offices, further shape engagement. Steps to address these gaps include investing in rural civic education programs and expanding urban outreach efforts to underrepresented neighborhoods. Conclusion: Geographic location is not merely a backdrop but an active force in shaping political attitudes and behaviors, demanding nuanced understanding and tailored approaches to effectively navigate its complexities.

Understanding Global Politics IA: Key Concepts and Real-World Applications

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Socioeconomic status significantly influences political behavior by determining access to resources, education, and opportunities. Higher-income individuals often have more political engagement, while lower-income groups may face barriers to participation, leading to differing policy preferences and voting patterns.

Education level correlates with political knowledge, critical thinking, and civic engagement. More educated individuals tend to be better informed about political issues, participate more actively in elections, and hold more nuanced political views compared to those with lower educational attainment.

Cultural and social norms shape political attitudes and behaviors by influencing values, beliefs, and group identities. For example, communities with strong religious or traditional norms may prioritize specific political issues, while individualistic cultures may emphasize personal freedoms and rights.

Media consumption plays a critical role in shaping political behavior by framing issues, disseminating information, and reinforcing or challenging existing beliefs. Exposure to diverse media sources can broaden perspectives, while echo chambers and biased media can polarize political opinions.

Generational differences influence political behavior due to varying experiences, values, and exposure to historical events. Younger generations often prioritize issues like climate change and social justice, while older generations may focus on economic stability and traditional values, leading to distinct political preferences and engagement styles.