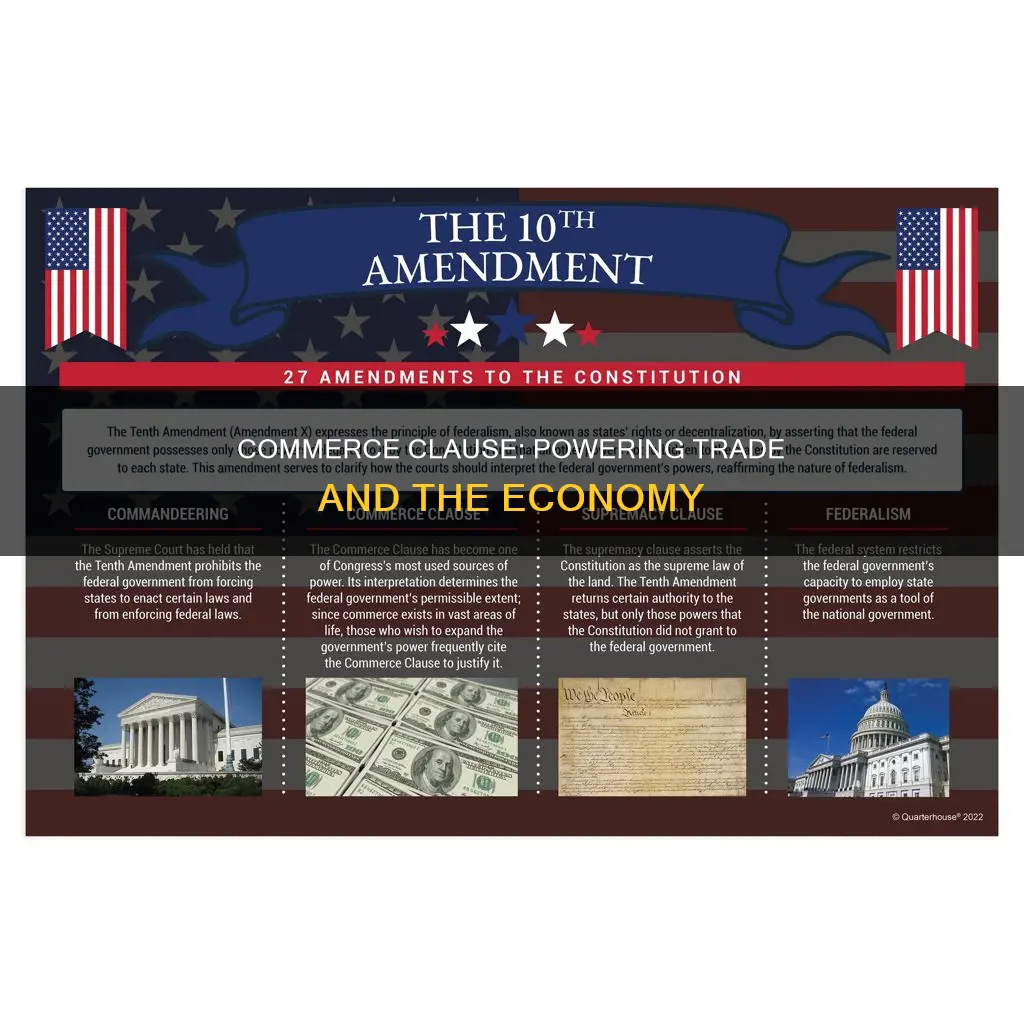

The Commerce Clause, found in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, grants Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, among several states, and with Indian tribes. The interpretation of the clause has evolved over time, with Congress using it to justify exercising legislative power over states and citizens, leading to ongoing debates about the balance of power between federal and state governments. The Supreme Court plays a critical role in interpreting the clause's reach, and its decisions have shaped the boundaries between federal and state powers. The Commerce Clause has been central to modern controversies, such as the Broccoli Argument, reflecting the ongoing tension between federal authority and personal freedoms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose | To address problems among the states that individual states are unable to deal with effectively |

| Framers' Response | To the absence of any federal commerce power under the Articles of Confederation |

| Powers Granted to Congress | To regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the states, and with Indian tribes |

| Powers Prohibited to States | Passing legislation that discriminates against or excessively burdens interstate commerce |

| Powers Prohibited to Congress | Passing laws that impede an individual's right to enter a business contract |

| Powers Interpreted by the Supreme Court | To cover various aspects of economic activity, as well as non-economic activity that substantially affects interstate commerce |

| Controversy | The balance of power between the federal government and the states, and the tension between federal authority and personal freedoms |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

- The Commerce Clause's role in shaping the boundaries between federal and state power

- The Framers' intent and the original meaning of the Commerce Clause

- The Dormant Commerce Clause and its implications for state legislation

- The Supreme Court's interpretation and application of the Commerce Clause

- The Commerce Clause's impact on Congress's ability to regulate economic activity

The Commerce Clause's role in shaping the boundaries between federal and state power

The Commerce Clause, found in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, grants Congress the power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes". The Commerce Clause has played a significant role in shaping the boundaries between federal and state power in the United States.

One of the primary purposes of the Commerce Clause was to eliminate trade barriers and create a unified economic front among the states. By granting Congress the power to regulate interstate commerce, the Commerce Clause aimed to prevent states from enacting discriminatory legislation that would impede the free flow of commerce between states. This is often referred to as the Dormant Commerce Clause, which suggests that even when Congress has not made laws about a certain area of trade, states cannot make rules that harm interstate business.

The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has evolved over time and has been the subject of intense political controversy. While some argue that "commerce" refers simply to trade or exchange, others claim that it describes a broader scope of commercial and social intercourse between citizens of different states. The Supreme Court has generally taken a broad interpretation of the clause, recognising that it can be used to regulate state activity if it has a "substantial economic effect" on interstate commerce.

The Commerce Clause has been invoked by Congress to justify exercising legislative power over state activities, leading to ongoing debates about the balance of power between the federal government and the states. For example, in United States v. Lopez (1995), the Supreme Court rejected the federal government's argument that regulating firearms in local schools fell under the Commerce Clause, asserting that Congress's power under the clause is limited to regulating channels of commerce, instrumentalities of commerce, and actions that substantially affect interstate commerce.

In conclusion, the Commerce Clause has played a pivotal role in shaping the boundaries between federal and state power. While it grants Congress broad powers to regulate interstate commerce and protect the interests of the American people, the Supreme Court has also placed limits on its reach to maintain the federal structure and protect personal freedoms. The ongoing interpretation and application of the Commerce Clause continue to shape the dynamic between federal and state authority in the United States.

Ohio vs US Constitution: What's the Difference?

You may want to see also

The Framers' intent and the original meaning of the Commerce Clause

The Commerce Clause, as outlined in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, states that the US Congress has the power to "regulate commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes".

The Framers' intent behind the Commerce Clause was to address the absence of any federal commerce power under the Articles of Confederation. The primary use of the Clause for the first century of its existence was to prevent discriminatory state legislation, which had once been permissible. The Framers wanted to ensure that commerce between the states was not limited by taxes or tariffs and that trade and exchange were promoted, rather than hindered by regulations.

The word "commerce" was regularly understood by the Framers of the Constitution and the general public at the time to mean "trade between states". However, the Constitution does not explicitly define the word "commerce", leading to debate over the range of powers granted to Congress by the Commerce Clause. Some scholars argue that the Framers intended "commerce" to refer simply to "'trade' or 'exchange'", while others claim that it was meant to describe a broader scope of commercial and social intercourse between citizens of different states.

In the 19th century, the Supreme Court held that intrastate activity could be regulated under the Commerce Clause, provided it was part of a larger interstate commercial scheme. This interpretation was broadened further in 1905 when the Court ruled that Congress could regulate local commerce as long as it could become part of a continuous "current" of commerce involving the interstate movement of goods and services.

From 1937 until 1995, the Supreme Court did not invalidate any laws on the basis of overstepping the Commerce Clause's grant of power. However, in 1995, the Court attempted to curtail Congress's broad legislative mandate under the Commerce Clause by returning to a more conservative interpretation.

PCA BCOs: Legally Bound or Free Agents?

You may want to see also

The Dormant Commerce Clause and its implications for state legislation

The Commerce Clause, as outlined in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, grants Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the states, and with Native American tribes. The clause has been interpreted broadly, with Congress using it to justify exercising legislative power over states and their citizens, leading to debates about the balance of power between federal and state governments.

The Dormant Commerce Clause, or Negative Commerce Clause, is a legal doctrine inferred from the Commerce Clause. It prohibits state legislation that discriminates against or excessively burdens interstate or international commerce, with a focus on barring state protectionism. This means that states may not pass laws that favour their own citizens or businesses over those from other states, as this would impede interstate commercial activity.

To determine if a law violates the Dormant Commerce Clause, courts first assess whether it discriminates against interstate commerce on its face. If the law is found to be discriminatory, the state must justify the local benefits of the law and demonstrate that there are no other means to achieve the same legitimate local purpose.

The Supreme Court has identified two key principles in its modern interpretation of the Dormant Commerce Clause. Firstly, states generally may not discriminate against interstate commerce. Secondly, states may not implement laws that appear neutral but unduly burden interstate commerce. For example, in the 2015 case of Comptroller of the Treasury of Maryland v. Wynne, the Court found Maryland's practice of taxing the personal income of its citizens earned both inside and outside the state, without tax credits for income tax paid to other states, to be a violation of the Dormant Commerce Clause.

The Dormant Commerce Clause has significant implications for state legislation, as it restricts states' ability to regulate commerce and pass laws that impede interstate commerce. This ensures a national market for goods and services, preserving economic unity.

Legal Notices: Mail Delivery and Its Legality

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Supreme Court's interpretation and application of the Commerce Clause

The Commerce Clause, outlined in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, states that the US Congress shall have the power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes". The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has been a subject of debate, with some arguing that it refers simply to trade or exchange, while others claim that it describes commercial and social intercourse between citizens of different states.

The Court's interpretation of the Commerce Clause took a significant turn in 1937, in the case of NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. In this case, the Supreme Court recognised broader grounds for using the Commerce Clause to regulate state activity, holding that any activity with a “substantial economic effect" on interstate commerce could be considered commerce. This marked the beginning of an era where the Court gave an unequivocally broad interpretation to the Commerce Clause.

The Supreme Court's interpretation of the Commerce Clause continued to evolve, and in United States v. Lopez (1995), the Court attempted to curtail Congress's broad legislative powers under the Commerce Clause by adopting a more conservative interpretation. In this case, the Court held that the federal government did not have the authority to regulate firearms in local schools, as it did not fall within the scope of regulating the channels of commerce, instrumentalities of commerce, or actions substantially affecting interstate commerce.

The Commerce Clause has also been invoked in cases related to public health and healthcare reform. For example, in NFIB v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court addressed the individual mandate in the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which required individuals to purchase health insurance. The Court held that this mandate could not be enacted under the Commerce Clause, as it was not the regulation of commercial activity. The Court's interpretation of the Commerce Clause in this case highlighted the complex and evolving nature of its jurisprudence.

In summary, the Supreme Court's interpretation and application of the Commerce Clause have evolved over time, with periods of both expansive and narrow interpretations. The Court's decisions have had significant implications for the balance of power between the federal government and the states, as well as for public policy areas such as health and economic regulation.

Restoring Lost Constitution: Icewind Dale Guide

You may want to see also

The Commerce Clause's impact on Congress's ability to regulate economic activity

The Commerce Clause, found in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, grants Congress the power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes". This clause has been interpreted to give Congress broad powers to regulate interstate commerce and restrict states from impairing interstate commerce. This includes the power to regulate the trade, transportation, or movement of persons and goods between states, foreign nations, and Indian tribes. However, it is important to note that the original meaning of the Commerce Clause did not include the power to regulate economic activities such as manufacturing or agriculture that produced the goods being traded or transported.

The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has evolved over time, with courts generally taking a broad interpretation of the clause for much of US history. The Supreme Court's early interpretations focused on the meaning of "commerce" rather than "regulate". The Court has also recognised broader grounds upon which the Commerce Clause could be used to regulate state activity, such as in NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp in 1937, where the Court held that an activity was considered commerce if it had a "substantial economic effect" on interstate commerce. This case marked the beginning of the Court's newfound willingness to interpret the Commerce Clause broadly.

The Commerce Clause has been used by Congress to justify exercising legislative power over the activities of states and their citizens, leading to ongoing controversies regarding the balance of power between the federal government and the states. The clause has been viewed as both a grant of congressional authority and a restriction on the regulatory authority of the states. The Supreme Court has played a crucial role in determining the reach of the Commerce Clause, with cases such as United States v. Lopez (1995) and National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012) highlighting the ongoing debate and tension between federal authority and personal freedoms in the application of the clause.

The Dormant Commerce Clause is a legal concept that suggests that even when Congress has not made laws about a specific trade area, states cannot create rules that harm interstate business. This prevents states from passing legislation that discriminates against or excessively burdens interstate commerce. For example, in West Lynn Creamery Inc. v. Healy, the Supreme Court struck down a Massachusetts state tax on milk products as it impeded interstate commercial activity by discriminating against non-Massachusetts citizens and businesses. The Dormant Commerce Clause protects against protectionist state policies that favour in-state citizens or businesses at the expense of out-of-state competitors.

In conclusion, the Commerce Clause has had a significant impact on Congress's ability to regulate economic activity by granting it broad powers to oversee interstate commerce and restrict states from impairing it. The interpretation of the clause has evolved over time, with ongoing debates about the balance of power between the federal government and the states. The Supreme Court continues to play a crucial role in determining the reach and application of the Commerce Clause, particularly in protecting against state laws that interfere with interstate commerce.

Exploring Supreme Court Duties: Constitutional Focus

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Commerce Clause is an enumerated power listed in the United States Constitution (Article I, Section 8, Clause 3). It grants Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the states, and with Indian tribes.

The Dormant Commerce Clause is a legal idea that suggests that even when Congress hasn't made laws about a certain area of trade, states cannot make rules that harm business between states.

The Commerce Clause emerged as a response to the absence of any federal commerce power under the Articles of Confederation. For the first century of its existence, it was used to preclude discriminatory state legislation. In 1887, with the enactment of the Interstate Commerce Act, Congress ushered in a new era of federal regulation under the Commerce Clause.

![The Commerce Clause of the Constitution and the Trusts 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)