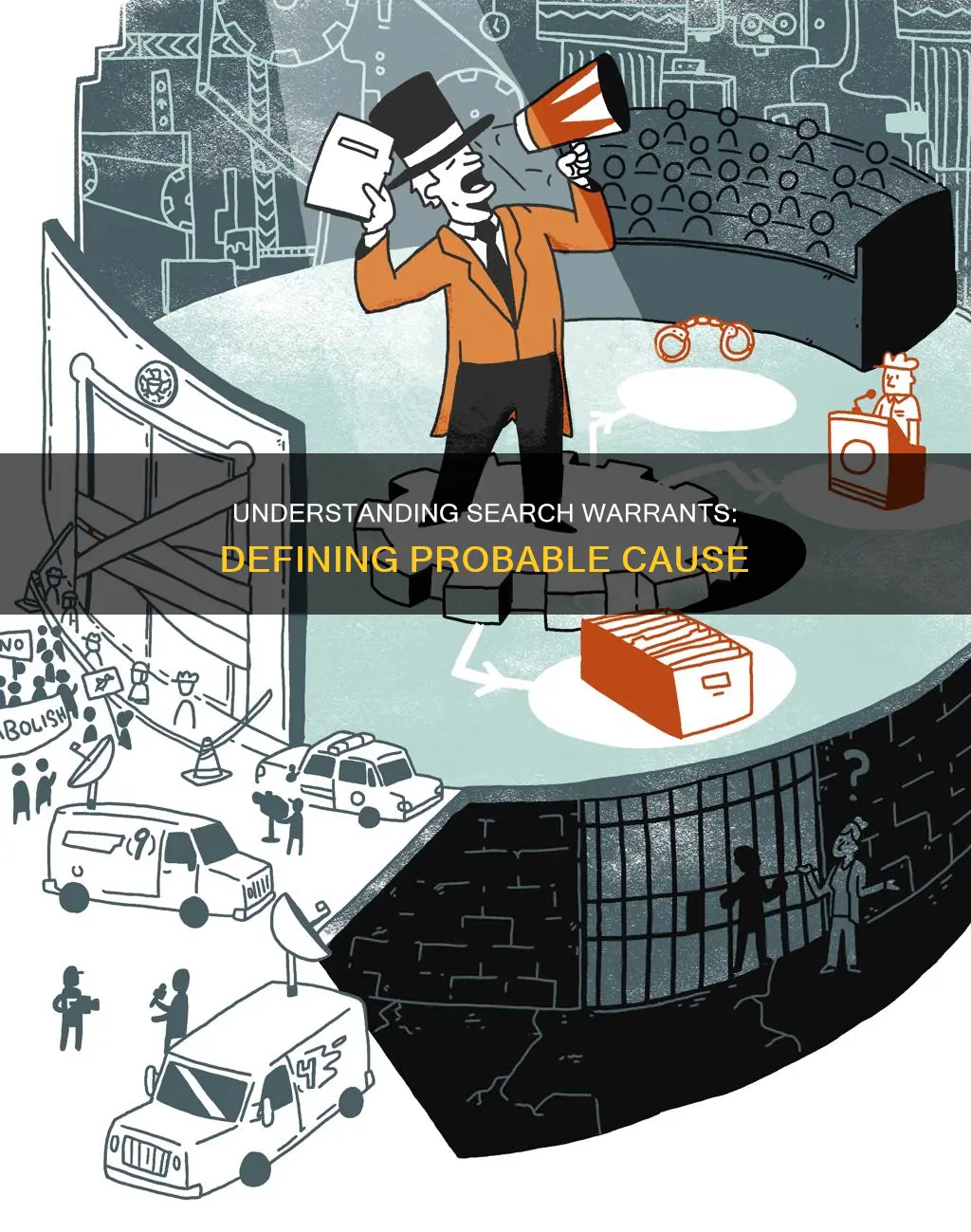

The Fourth Amendment protects people from unlawful government searches and seizures, stating that no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause. However, the amendment does not define probable cause, leaving the exact meaning of the term open to interpretation by the courts. Probable cause is generally understood to be reasonable grounds to believe that a crime has been, is being, or will be committed. In the context of a search warrant, probable cause is established when there is reasonable belief that evidence of a crime will be found in a particular place. An officer will typically sign an affidavit stating the facts they know from their observations or those of citizens and police informants, which is then presented to a judge or magistrate who decides whether to issue a warrant.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reasonable belief that a crime was committed, is being committed, or will be committed | A reasonable person would believe that a crime was in the process of being committed, had been committed, or was going to be committed |

| Reasonable grounds | The affiant had reasonable grounds at the time of the affidavit |

| Reasonably trustworthy information | Police have reasonably trustworthy information sufficient to warrant a reasonable person to believe that a particular person has committed or is committing an offense |

| Oath or affirmation | The warrant is supported by an oath or affirmation |

| Description of place to be searched | The warrant should particularly describe the place to be searched |

| Description of persons or things to be seized | The warrant should particularly describe the persons or things to be seized |

| Totality of the circumstances | The totality of the circumstances, meaning everything that the arresting officers know or reasonably believe at the time the arrest is made |

| Reasonable grounds for evidence of illegality | The officer should give reasonable grounds to support the possibility that evidence of illegality will be found |

| Affidavit | The affidavit in support of the warrant offers sufficient credible information to establish probable cause |

| Anticipatory warrants | Police officers are not required to believe that contraband is in a certain place to be searched |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The role of the Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects people's right to privacy and freedom from unreasonable government intrusion. It states that:

> [t]he right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

The Fourth Amendment requires that any arrest be based on probable cause, even when the arrest is made pursuant to an arrest warrant. Probable cause is a flexible concept, and whether or not it exists typically depends on the totality of the circumstances, including all the information that the arresting officers know or reasonably believe at the time. Probable cause is a requirement that must usually be met before police make an arrest, conduct a search, or receive a warrant.

The concept of "probable cause" is central to the meaning of the warrant clause. While the Fourth Amendment does not define "probable cause", it generally means that a reasonable person would believe that a crime was in the process of being committed, had been committed, or was going to be committed. Probable cause can be established through police officers' observations, information from victims or witnesses, and information received from informants.

The Fourth Amendment generally prohibits warrantless searches of private premises, unless a specific exception applies, such as when an officer has consent to search, when the search is incident to a lawful arrest, when there is probable cause to search and there are exigent circumstances, or when items are in plain view.

The Main Person's Guide to Writing the Constitution

You may want to see also

Reasonable suspicion vs probable cause

The terms "reasonable suspicion" and "probable cause" are often confused and misused. While both are related to a police officer's overall impression of a situation, they have distinct legal implications and different repercussions on an individual's rights, the proper protocol, and the outcome of the situation.

Reasonable suspicion is a legal standard that allows law enforcement officers to briefly stop, frisk, detain, and question individuals based on specific facts or circumstances that suggest criminal activity. It is more than just a hunch but does not require the higher standard of probable cause needed for an arrest or search. In other words, reasonable suspicion is a step before probable cause. At this point, it appears that a crime may have been committed. An officer with reasonable suspicion may frisk or detain the suspect briefly, but they cannot search a person or a vehicle unless they are on school property.

Probable cause generally means that a reasonable person would believe that a crime was in the process of being committed, had been committed, or was going to be committed. It requires a substantial degree of certainty and more than mere suspicion. Probable cause can justify a more thorough search or an arrest. To obtain a search warrant, a court must consider whether, based on the totality of the information, there is a fair probability that contraband, evidence, or a person will be found in a particular place. A judge may issue a search warrant if the affidavit in support of the warrant offers sufficient credible information to establish probable cause. Probable cause is typically enough for a search or arrest warrant and for a police officer to arrest if they observe a crime being committed.

Understanding the difference between reasonable suspicion and probable cause is crucial to determining the legality of police stops, searches, and arrests. If law enforcement actions aren’t based on either of these, any evidence obtained can be challenged and possibly excluded from court proceedings.

Citing the Constitution: Works Cited Entry?

You may want to see also

Probable cause and digital data

The Fourth Amendment protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures, stating that "no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause". However, the Fourth Amendment does not define "probable cause", leaving the exact meaning of the term open to interpretation by the Supreme Court.

Probable cause is a flexible concept, dependent on the totality of the circumstances and the court's interpretation of the reasonableness standard. Generally, it means that a reasonable person would believe that a crime was in the process of being committed, had been committed, or was going to be committed. In the context of digital data, probable cause is established when there is a reasonable basis for believing that evidence of a crime is present on the device to be searched.

In the 2014 case of Riley v. California, the Supreme Court held that law enforcement may not search the contents of digital devices without a warrant or the owner's consent. This decision recognised that electronic devices contain vast amounts of private information, distinguishing them from physical items like wallets. As such, when a digital device is recovered in a standard search and seizure, law enforcement must preserve the device and wait for a warrant authorising a search of its contents.

To obtain a search warrant for digital data, law enforcement must establish probable cause and describe in detail the data to be taken. The warrant must be particular and specific, narrowly tailored to avoid unreasonable intrusion into the suspect's digital life. The probable cause standard is satisfied when the affidavit establishes "a fair probability that contraband or evidence of a crime will be found in a particular place". The affidavit must also include credible information, such as observations made by police officers, information from victims or witnesses, and the officer's experience and training.

It is important to note that there are exceptions to the warrant requirement. For example, consent is given if the person with authority over the device voluntarily consents to the search. Additionally, under exigent circumstances, probable cause can justify a warrantless search or seizure.

Understanding Malpractice: Incapacitated Patients in Nursing Homes

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Anticipatory warrants

For example, in the Grubbs case, agents of the U.S. Postal Service wanted to search Mr. Grubbs' house after delivering a child pornographic videotape that he had ordered from a website. They wanted to get the warrant before the delivery so that they could conduct the search immediately after the delivery was made. They knew that the parcel wasn't in Mr. Grubbs' house at the time they requested the warrant, but they requested the warrant be issued in anticipation of the delivery. Once the triggering event of the parcel being delivered and taken into the house occurred, the warrant could be executed.

To obtain an anticipatory warrant, officers must provide probable cause not only that the evidence will be present once the triggering event occurs but also that the triggering event will occur. This triggering event must be some identifiable event other than the passage of time. In the Grubbs case, the delivery of the parcel was the triggering event.

Probable cause is a requirement found in the Fourth Amendment that must usually be met before police make an arrest, conduct a search, or receive a warrant. It typically depends on the totality of the circumstances, meaning everything that the arresting officers know or reasonably believe at the time. Probable cause is a flexible concept, and what constitutes the "totality of the circumstances" can depend on how the court interprets the reasonableness standard. Probable cause has been defined as a reasonable basis for believing that a crime may have been committed (for an arrest) or when evidence of a crime is present in the place to be searched (for a search).

Who Approves Cabinet Members? The Senate's Role Explained

You may want to see also

The exclusionary rule

In Davis v. U.S., the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the exclusionary rule does not apply when the police conduct a search in reliance on binding appellate precedent allowing the search. Under Illinois v. Krull, evidence may be admissible if the officers rely on a statute that is later invalidated. In Herring v. U.S., the Court found that the good-faith exception to the exclusionary rule applies when police employees erred in maintaining records in a warrant database.

Additionally, some courts recognize an "expanded" doctrine, in which a partially tainted warrant is upheld if, after excluding the tainted information that led to its issuance, the remaining untainted information establishes probable cause. The exclusionary rule is inapplicable to evidence obtained by an officer acting in objectively reasonable reliance on a statute later held to violate the Fourth Amendment.

Citing the Irish Constitution: A Quick Bibliography Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Probable cause is a requirement found in the Fourth Amendment that must usually be met before police make an arrest, conduct a search, or receive a warrant. Probable cause means that a reasonable person would believe that a crime was in the process of being committed, had been committed, or was going to be committed.

Probable cause for a search warrant exists when facts and circumstances known to the law enforcement officer provide the basis for a reasonable person to believe that they committed a crime at the place to be searched or that evidence of a crime exists at the location.

To obtain a search warrant, an officer will sign an affidavit stating the facts the officer knows from their own observations. They can also base their affidavit on the observations of citizens or police informants. If a judge or magistrate agrees that probable cause exists based on the "totality of the circumstances", they will issue a search warrant.

Yes, there are a few exceptions. For example, if the officer has probable cause to believe that an automobile contains evidence of a crime or contraband, they can search the vehicle without a warrant. Additionally, in certain cases, a K-9 sniff in a public area may provide enough probable cause for an officer to obtain a warrant.

![Probable Cause: Series (Probable Cause: The Human Factor / Mechanics of Failure / Unseen Dangers / Acceptable Risk) [Region 2]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81IWaEOZbnL._AC_UY218_.jpg)