Sanger sequencing is a widely used method for determining the precise order of nucleotides in a DNA molecule. The output of Sanger sequencing is a chromatogram, which represents the migration of labelled sequencing products. A good Sanger reading on a chromatograph is one that is free from common artifacts that can compromise data accuracy, such as dye blobs, primer dimers, and stutter peaks. The highest-quality data will typically occur between positions 100 and 500 in the trace. Optimizing PCR conditions and adhering to sound laboratory practices can help to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | High accuracy due to ability to analyze genetic markers like SNPs and STRs, generate reliable DNA profiles, and resolve complex clinical cases |

| Speed | High-quality data in as fast as a few hours |

| Data Output | Chromatogram (trace or ab1 file) and a text-based sequence file |

| Visualization | Visual inspection of the chromatogram is necessary for accurate interpretation |

| Peak Characteristics | Abnormal peaks may indicate poor DNA quality, inadequate template purity, degradation, contamination, or instrument malfunction |

| Peak Correction | Relative position of peaks must be adjusted to compensate for differences in dye mobility properties |

| Quality Metrics | Quality values (QVs) are assigned to each base to evaluate the reliability of the output sequence |

| Artifacts | Dye blobs and primer dimers can interfere with accurate sequence reading |

| PCR Conditions | Optimizing conditions such as using higher-fidelity polymerases, reducing PCR cycles, and adjusting annealing temperatures can help mitigate biases and artifacts |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The importance of chromatogram analysis

A chromatogram, also known as a trace or ab1 file, is an output of Sanger sequencing. It represents the migration of labelled sequencing products through capillary electrophoresis, with fluorescence detected at the end of the capillary. The signal intensity from four colour channels, each representing a DNA base, is plotted on the y-axis relative to time. This process allows for the determination of the precise order of nucleotides (adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine) in a DNA molecule.

Optimizing the sequencing reaction conditions is essential to mitigate these issues. This includes adjusting primer concentrations, using higher-purity reagents, and employing enzymatic cleanup steps to remove unincorporated dyes and primers. Additionally, adhering to sound laboratory practices, such as utilizing dedicated PCR workstations and sterile disposable pipette tips, helps to counteract non-specific amplification and improve data quality.

Through a comprehensive understanding of chromatogram analysis and the implementation of effective strategies, researchers can enhance the accuracy and reliability of Sanger sequencing results. This, in turn, contributes to advancements in genetics and clinical investigations, making chromatogram analysis an indispensable tool in modern scientific research.

The Constitution's Take on a Standing Army

You may want to see also

The fundamentals of Sanger DNA sequencing

Sanger sequencing, also known as the "

The process begins with a sequencing reaction containing the DNA template, primers, DNA polymerase, deoxynucleotides, and fluorescently labelled dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs). DNA polymerase synthesises new DNA strands using the template DNA as a blueprint. However, the incorporation of ddNTPs terminates DNA synthesis due to their lacking 3'-OH group. Each ddNTP is tagged with a unique fluorescent dye, corresponding to a specific base.

After the sequencing reaction, the resulting DNA fragments, each labelled with a fluorescent dye, undergo capillary electrophoresis, which separates the fragments based on size. Smaller fragments migrate faster, and a detector reads the fluorescent signals, generating a chromatogram that represents the sequence data.

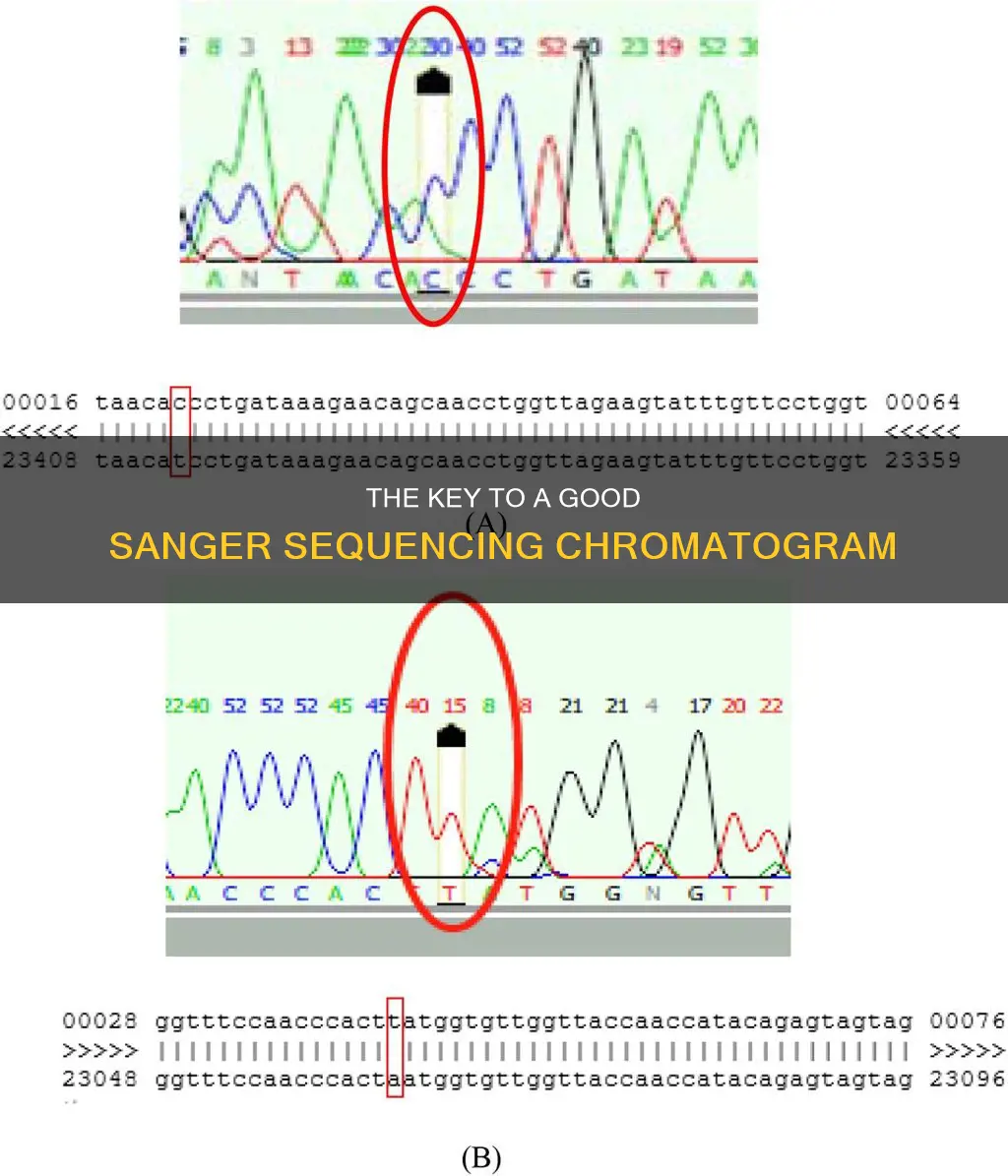

The output for Sanger sequencing is typically a chromatogram, which contains valuable data that speaks to the accuracy of the generated sequence. Abnormal peaks in a chromatogram can be caused by poor DNA quality, contaminating DNA or RNA, or insufficient denaturation of the DNA template. Dye blobs and primer dimers are common artifacts that can compromise data accuracy.

Sanger sequencing can be performed manually or, more commonly, in an automated fashion using a sequencing machine. In manual Sanger sequencing, four PCR reactions are set up, each with a single type of ddNTP. In automated Sanger sequencing, all ddNTPs are mixed in a single reaction, and each of the four dNTPs has a unique fluorescent label. The automated method provides high-quality data in as little as a few hours.

Executive Power: Constitutional Definition and Limits

You may want to see also

Common pitfalls and how to address them

One of the most common issues encountered when working with Sanger sequencing is the presence of abnormal peaks in the chromatogram. These abnormal peaks can be caused by a variety of factors, such as poor DNA quality due to template impurity or degradation, contaminating DNA or RNA, and insufficient denaturation of the DNA template. To address these issues, it is important to ensure the purity of the DNA template and prevent degradation. Contamination can be avoided by purifying the PCR product, thereby eliminating contaminants that interfere with the sequencing reaction.

Another issue is low signal intensity, which can lead to weak signals or no peaks in specific regions of the chromatogram. This can be caused by low DNA template concentration, insufficient amplification, or problems with primer binding. To address low signal intensity, the setup of the sequencing reaction can be optimised by increasing the amount of DNA template used and ensuring optimal primer annealing temperatures and concentrations.

Dye blobs are another common pitfall, manifesting as broad peaks with unusual shapes and masking the true signal. They are caused by unincorporated dye in the sequencing reaction, leading to background noise. To resolve this issue, enzymatic cleanup steps can be employed to remove unincorporated dyes and primers.

Primer dimers are also a common issue, formed when primers anneal to each other instead of the target DNA. This results in non-specific products that generate peaks in the early part of the chromatogram, potentially interfering with accurate sequence reading. Optimising the sequencing reaction conditions, such as adjusting primer concentrations and using higher-purity reagents, can help address this issue.

Additionally, chromatograms may show a lot of noise or background along the bottom of the trace, interfering with base calling. This is often due to low sample signal intensity, which can be addressed by ensuring optimal template concentrations and primer binding efficiency.

Finally, it is important to be aware of technical lapses in chromatogram interpretation, as automated algorithms may not comprehensively assess sequencing data quality. Therefore, it is crucial to visually inspect all traces and employ software tools and techniques like bidirectional sequencing to enhance the accuracy and reliability of the results.

Citing a Constitution: Chicago Style Bibliography Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Strategies to overcome hurdles in Sanger sequencing analysis

Sanger sequencing is a widely used method for determining the precise order of nucleotides in a DNA molecule. It is an essential tool for researchers worldwide and has revolutionized the field of genetics. However, despite careful optimization, Sanger sequencing can be susceptible to artifacts and other technical challenges that may compromise data accuracy. Here are some strategies to overcome these hurdles and improve the reliability of Sanger sequencing analysis:

Start with High-Quality Samples

Begin by selecting the highest-quality DNA samples available. Ensure that the DNA is as intact as possible, even if it is slightly degraded. This initial step is crucial and makes a significant difference in the sequencing process.

Implement Rigorous Quality Control

Before sequencing, conduct thorough quality control measures, including DNA quantification to determine the concentration and assessing integrity through gel electrophoresis. These steps help identify the suitability of your samples for sequencing and ensure that they meet the required standards.

Optimize DNA Preparation

Use specialized techniques to repair and prepare degraded DNA samples. This may involve enzymatic treatments or purification steps to stabilize the sample and remove contaminants that could interfere with sequencing. These steps enhance the integrity of the DNA and improve the reliability of the sequencing results.

Optimize Electrophoresis Conditions

Fine-tune electrophoresis parameters such as voltage, temperature, and polymer concentration. This adjustment can improve peak separation and minimize overlap, making it easier to distinguish individual base calls and reducing the potential for errors.

Employ High-Resolution Matrices

Utilize specialized polymers or matrices designed for high-resolution separations. These matrices enhance the discrimination of DNA fragments with minor size differences, reducing peak overlap. This technique improves the accuracy of base calling by minimizing the challenges associated with overlapping peaks.

Adjust Sequencing Chemistry

Modify the sequencing chemistry by using different fluorescent dyes or optimizing the ratio of ddNTPs to dNTPs. These adjustments can impact peak shape and spacing, allowing for better differentiation between authentic signals and background interference.

Visual Inspection and Advanced Software Analysis

While many automated tools are available for analyzing Sanger data, visual inspection of the chromatogram is crucial. Combine this with advanced software analysis, which employs sophisticated algorithms to process and interpret raw data, providing more accurate and efficient data analysis.

By implementing these strategies, researchers can enhance the accuracy, reliability, and quality of Sanger sequencing analysis, thereby improving the overall effectiveness of their experiments and gaining deeper insights into their research.

Enumerated Powers: Expanding Federal Reach and Authority

You may want to see also

Interpreting chromatograms accurately

Understand the Fundamentals of Sanger Sequencing

To accurately interpret chromatogram data, it is crucial to grasp the underlying principles of Sanger DNA sequencing. This process involves a sequencing reaction containing a DNA template, primers, DNA polymerase, deoxynucleotides, and fluorescently labelled dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs). Each ddNTP is tagged with a unique fluorescent dye, and DNA polymerase synthesises new DNA strands using the template DNA as a guide. The incorporation of ddNTPs terminates DNA synthesis at specific points, generating fragments of varying lengths. These fragments are then separated based on size through capillary electrophoresis, and a detector reads the fluorescent signals, producing a chromatogram.

Recognise Common Artifacts and Pitfalls

Sanger sequencing data can be susceptible to artifacts and technical errors that compromise accuracy. Common issues include dye blobs, which manifest as broad peaks with unusual shapes and can mask the true signal. Primer dimers are another challenge, forming when primers bind to each other instead of the target DNA, resulting in early peaks that may interfere with sequence reading. Additionally, stutter peaks can introduce complexity, appearing as small peaks before or after the genuine signal peak and potentially leading to incorrect base calling.

Address Abnormal Peaks

Abnormal peaks in a chromatogram can arise from various factors, including poor DNA quality, contamination, or insufficient denaturation of the DNA template. It is important to systematically troubleshoot and identify the root cause of abnormal peaks to ensure accurate interpretation. For example, optimizing PCR conditions, such as using higher-fidelity polymerases or reducing PCR cycles, can help mitigate PCR bias and artifact formation.

Utilise Quality Metrics and Visual Inspection

To determine the reliability of the output sequence, it is essential to employ quality metrics and visually inspect the chromatogram. Automated tools are available for analyzing Sanger data, but visual inspection remains indispensable. The highest quality data and most accurate base calling typically occur between positions 100 and 500 in the trace. By evaluating the data with quality metrics and a critical eye, you can ensure the accuracy and reliability of your interpretations.

Implement Systematic Troubleshooting

When encountering issues with Sanger sequencing data, a systematic approach to troubleshooting is vital. This includes recognizing common limitations, such as those associated with reading DNA chromatograms of smaller amplicons, and taking measures to mitigate their impact. For example, careful optimization of sequencing reaction conditions, such as adjusting primer concentrations or using higher-purity reagents, can address artifacts and improve data quality.

Congressional Division: Understanding Constitutional Design

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A chromatogram is a visual representation of the migration of labelled sequencing products via capillary electrophoresis. It is an output of Sanger sequencing, which is a widely used method for determining the precise order of nucleotides in a DNA molecule.

Some common issues that can affect the accuracy of Sanger sequencing and, consequently, the reading of a chromatogram include dye blobs, primer dimers, abnormal peaks, stutter peaks, and contamination. These issues can lead to background noise, peak broadening, tailing, or splitting, compromising the accuracy of the sequencing results.

To improve the accuracy of Sanger sequencing and the reading of chromatograms, it is important to optimise the PCR conditions, such as using higher-fidelity polymerases, reducing PCR cycles, and adjusting annealing temperatures. Additionally, visual inspection of the chromatogram is crucial, as automated tools may not always provide accurate interpretations.