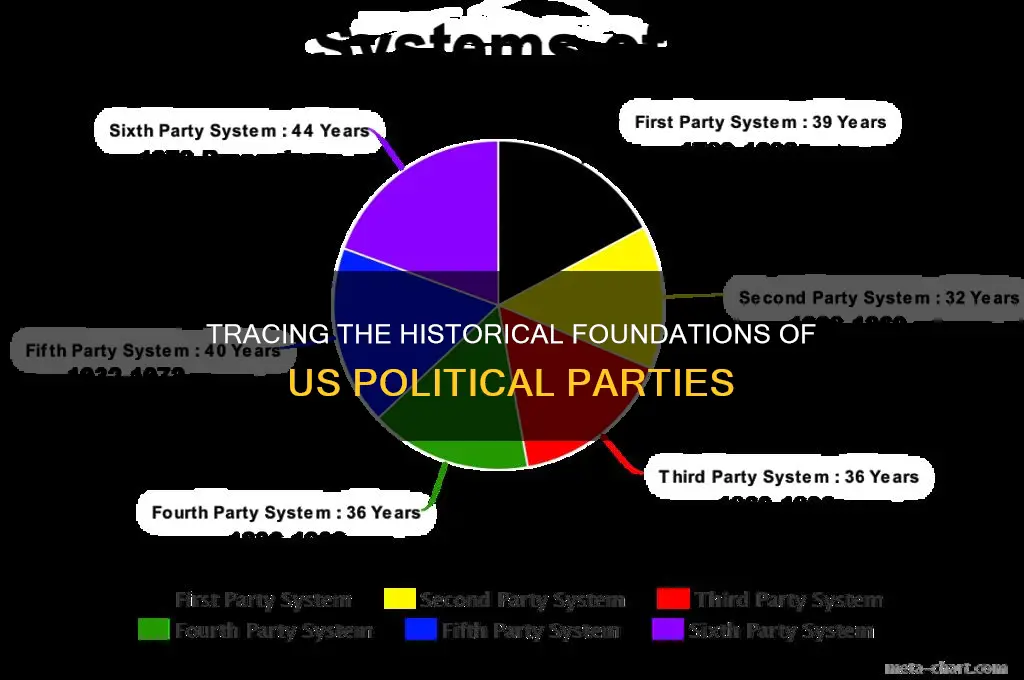

The roots of political parties in the United States trace back to the early years of the nation's founding, emerging from ideological and policy disagreements among the country's earliest leaders. Initially, the Founding Fathers, including George Washington, were wary of political factions, fearing they would undermine unity and stability. However, by the 1790s, deep divisions over issues such as the role of the federal government, economic policies, and foreign relations led to the formation of the first two major parties: the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, who advocated for a strong central government and industrialization, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who championed states' rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal power. These early conflicts laid the groundwork for the two-party system that continues to shape American politics today, reflecting enduring debates about governance, individual rights, and the nation's identity.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Historical Origins | Rooted in the early 19th century, emerging from debates over federal power, states' rights, and economic policies. |

| Founding Parties | Democratic-Republican Party (Jeffersonian) and Federalist Party. |

| Key Issues at Inception | Centralized vs. decentralized government, banking, and tariffs. |

| Evolution of Parties | Democratic Party and Republican Party emerged in the mid-19th century. |

| Civil War Impact | Solidified party divisions over slavery and states' rights. |

| Progressive Era Influence | Introduced reforms and expanded government roles, shaping modern platforms. |

| Modern Party Alignment | Democrats (liberal, progressive) vs. Republicans (conservative). |

| Geographic Roots | Democrats initially strong in the South, Republicans in the North. |

| Economic Roots | Democrats associated with agrarian interests, Republicans with industrial. |

| Social and Cultural Roots | Parties evolved to reflect social movements (e.g., civil rights, conservatism). |

| Current Ideological Divide | Democrats focus on social welfare, diversity, and regulation; Republicans on limited government and free markets. |

| Demographic Shifts | Democrats attract urban, minority, and younger voters; Republicans rural, white, and older voters. |

| Media and Technology Influence | Modern parties shaped by digital campaigns, social media, and polarized media outlets. |

| Global Context | Parties influenced by global trends like globalization, climate change, and populism. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Origins: Early factions, Federalist vs. Democratic-Republican, and the two-party system's emergence

- Ideological Foundations: Liberalism, conservatism, and the role of core beliefs in party formation

- Regional Influences: Sectionalism, slavery, and geographic divides shaping party identities

- Key Figures: Leaders like Jefferson, Hamilton, and their impact on party development

- Structural Factors: Electoral systems, primaries, and institutional rules reinforcing party dominance

Historical Origins: Early factions, Federalist vs. Democratic-Republican, and the two-party system's emergence

The roots of political parties in the United States can be traced back to the early years of the nation's formation, when differing visions for the country's future gave rise to competing factions. During the 1790s, as the United States began to establish its government under the Constitution, two dominant groups emerged: the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. These factions were not yet formal political parties in the modern sense but represented distinct ideologies and interests that would lay the groundwork for the two-party system.

The Federalists, who dominated the early years of the Washington administration, advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and close ties with Britain. Hamilton, as Secretary of the Treasury, pushed for policies like the assumption of state debts and the creation of a national financial system, which he believed were essential for economic stability and national unity. Federalists drew support from merchants, urban elites, and New England, where a strong central authority was seen as crucial for protecting commercial interests. In contrast, the Democratic-Republicans, rooted in the agrarian South and West, feared centralized power and favored states' rights, strict interpretation of the Constitution, and a more egalitarian society. Jefferson and Madison criticized Federalist policies as elitist and a threat to individual liberties.

The rivalry between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans intensified during the 1790s, fueled by debates over foreign policy, the Jay Treaty with Britain, and the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Democratic-Republicans viewed Federalist policies as monarchical and anti-democratic, while Federalists accused their opponents of being radical and destabilizing. The election of 1800, in which Jefferson defeated Federalist incumbent John Adams, marked a pivotal moment in the emergence of the two-party system. Known as the "Revolution of 1800," this peaceful transfer of power demonstrated the viability of partisan competition as a mechanism for resolving political differences.

The Federalist Party declined after 1800, largely due to its association with unpopular policies and regional limitations, while the Democratic-Republicans became the dominant political force. However, internal divisions within the Democratic-Republican Party eventually led to the emergence of a new two-party system. By the 1820s, the party split into two factions: the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, which inherited some Federalist ideas and opposed Jacksonian democracy. This period solidified the two-party structure as a central feature of American politics, with competing parties mobilizing voters and shaping policy debates.

The historical origins of political parties in the U.S. thus reflect the nation's early struggles to define its identity and governance. The Federalist-Democratic-Republican rivalry established the framework for partisan competition, while the evolution of these factions into the Democratic and Whig Parties cemented the two-party system. These early developments highlight the enduring tension between centralized authority and states' rights, as well as the role of political parties in articulating and advancing competing visions for the nation.

Global Leaders Backing UNICEF: Who Supports Children's Rights Worldwide?

You may want to see also

Ideological Foundations: Liberalism, conservatism, and the role of core beliefs in party formation

The roots of political parties in the United States are deeply intertwined with the ideological foundations of liberalism and conservatism, which have shaped the nation's political landscape since its inception. These core beliefs have not only defined the principles of the Democratic and Republican parties but also influenced their formation, evolution, and enduring rivalry. Liberalism, rooted in the Enlightenment ideals of individual liberty, equality, and the protection of rights, has been a cornerstone of the Democratic Party. Early American liberals, such as Thomas Jefferson, championed limited government intervention in personal affairs, states' rights, and the separation of church and state. Over time, liberalism in the U.S. evolved to emphasize social justice, economic equality, and the role of government in ensuring opportunity for all, particularly through progressive reforms and social safety nets.

Conservatism, on the other hand, draws from traditions of order, hierarchy, and the preservation of established institutions. The Republican Party, influenced by thinkers like Alexander Hamilton, initially focused on strong central government, economic nationalism, and the protection of property rights. Modern American conservatism, however, has come to prioritize free markets, limited government, traditional values, and a strong national defense. Conservatives often emphasize individual responsibility and skepticism of expansive government programs, viewing them as potential threats to personal freedom and economic efficiency. These contrasting ideologies have created a dynamic tension that fuels party formation and political competition.

The role of core beliefs in party formation cannot be overstated, as they provide the intellectual and moral frameworks that attract adherents and guide policy agendas. For instance, the Democratic Party's liberal ideology has historically united diverse groups—labor unions, civil rights activists, environmentalists, and progressives—around a shared commitment to social and economic equality. Similarly, the Republican Party's conservative principles have rallied supporters around themes of fiscal responsibility, national security, and cultural traditionalism. These core beliefs serve as rallying points, helping parties mobilize voters and differentiate themselves in a crowded political arena.

The interplay between liberalism and conservatism has also shaped the structure and strategies of political parties. In the early years of the republic, ideological differences led to the formation of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, precursors to today's two-party system. As societal issues evolved—such as slavery, industrialization, and civil rights—these ideological foundations adapted, but their essence remained central to party identity. For example, the Democratic Party's shift from a states' rights, agrarian focus to a more urban, socially progressive stance reflects the adaptability of liberal ideals to changing circumstances.

Ultimately, the ideological foundations of liberalism and conservatism are not static but have evolved in response to historical, economic, and social changes. This evolution has allowed political parties to remain relevant while staying true to their core beliefs. The enduring strength of these ideologies lies in their ability to resonate with fundamental human values—liberty, equality, and order—and to provide coherent frameworks for addressing complex political challenges. As such, understanding the roots of political parties in the U.S. requires a deep appreciation of how these ideologies have shaped, and continue to shape, the nation's political identity.

Greta Thunberg's Political Impact: Activism, Influence, and Global Change

You may want to see also

Regional Influences: Sectionalism, slavery, and geographic divides shaping party identities

The roots of political parties in the United States are deeply intertwined with regional influences, particularly the forces of sectionalism, slavery, and geographic divides. In the early years of the republic, these factors played a pivotal role in shaping the identities of the emerging political parties. Sectionalism, the loyalty to one's region over the nation as a whole, became a defining characteristic of American politics. The North and the South developed distinct economic, social, and cultural identities, which inevitably influenced their political priorities and alliances. The North, with its industrial economy and growing urban centers, clashed with the agrarian, slave-dependent South, setting the stage for political polarization.

Slavery emerged as the most contentious issue exacerbating regional divides. The Southern states, heavily reliant on enslaved labor for their plantation economy, fiercely defended the institution, while Northern states, where slavery was less prevalent or had been abolished, increasingly viewed it as morally repugnant and economically backward. This divide was not merely economic but also ideological, as it touched on fundamental questions of liberty, equality, and human rights. The Democratic Party, rooted in the agrarian South, became the primary defender of slavery, while the emerging Republican Party in the North positioned itself as the antislavery alternative. This alignment of parties with regional interests and moral stances solidified their identities and set the groundwork for future conflicts.

Geographic divides further reinforced these party identities. The North’s industrial growth and diverse population contrasted sharply with the South’s rural, agrarian society. Western territories, as they were settled, became battlegrounds for competing visions of the nation’s future. Should new states be admitted as free or slave states? This question dominated political discourse and deepened the rift between the parties. The Democratic Party, with its base in the South and parts of the West, advocated for states’ rights and the expansion of slavery, while the Republicans, rooted in the North, championed federal authority and the containment or abolition of slavery. These geographic and ideological divides were not just about policy but also about the soul of the nation.

The impact of these regional influences was most dramatically illustrated in the lead-up to the Civil War. The Whig Party, which had attempted to straddle the North-South divide, collapsed under the weight of the slavery issue, giving rise to the Republican Party as the dominant force in the North. The Democratic Party, meanwhile, became increasingly identified with the Southern cause. The election of Abraham Lincoln, a Republican, in 1860 was a direct result of these regional and party alignments, as it signaled the North’s ascendancy and the South’s alienation, ultimately leading to secession. Thus, sectionalism, slavery, and geographic divides were not just background factors but central forces in shaping the identities and trajectories of American political parties.

Even after the Civil War, the legacy of these regional influences persisted, reshaping party identities in the Reconstruction era and beyond. The Republican Party, associated with the Union victory and emancipation, dominated national politics, while the Democratic Party struggled to redefine itself in the post-slavery South. The Solid South, a bloc of Democratic-voting states, emerged as a reaction to Republican policies and the imposition of federal authority, reflecting the enduring power of regional loyalties. Geographic divides continued to play a role, as the West became a key battleground for economic and social policies, with parties vying to represent the interests of farmers, miners, and industrialists. In this way, the regional influences of the early republic continued to shape American political parties well into the 20th century, demonstrating their lasting impact on the nation’s political landscape.

Understanding Politics: The Vital Role and Work of Political Scientists

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$28.31 $42

Key Figures: Leaders like Jefferson, Hamilton, and their impact on party development

The roots of political parties in the United States can be traced back to the early years of the republic, with key figures like Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton playing pivotal roles in shaping the nation's partisan landscape. Their ideological differences and personal rivalries laid the groundwork for the emergence of the first political parties, setting the stage for the two-party system that continues to dominate American politics today. Jefferson, a staunch advocate for states' rights and agrarian interests, clashed with Hamilton, a champion of a strong central government and industrialization, over the direction of the new nation. These disagreements not only defined their legacies but also catalyzed the formation of organized political factions.

Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, became the leader of the Democratic-Republican Party, which emphasized limited federal government, strict interpretation of the Constitution, and the rights of states and farmers. Jefferson's vision was deeply rooted in his belief in an agrarian society, where power was decentralized and citizens maintained a direct connection to the land. His presidency, from 1801 to 1809, marked the first time a political party came to power through an election, solidifying the role of parties in American governance. Jefferson's ability to mobilize supporters and articulate a coherent ideology helped establish the Democratic-Republicans as a dominant force in early 19th-century politics.

Alexander Hamilton, on the other hand, was the architect of the Federalist Party, which advocated for a strong central government, a national bank, and policies favoring commerce and industry. As the first Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton's economic programs, such as the assumption of state debts and the creation of a national bank, were controversial but instrumental in stabilizing the new nation's finances. His vision of a modern, industrialized America clashed with Jefferson's agrarian ideal, creating a deep ideological divide. Hamilton's Federalist Party, though less successful in the long term, played a crucial role in early party development by providing a clear alternative to Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans and fostering a system of political competition.

The rivalry between Jefferson and Hamilton was not merely about policy but also about the fundamental nature of American democracy. Their debates over the Constitution, the role of government, and the economy polarized the political elite and the public, leading to the formation of distinct partisan identities. For instance, the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, sparked by Hamilton's excise tax on distilled spirits, highlighted the tensions between Federalist policies and Jeffersonian ideals, further entrenching party divisions. These early conflicts demonstrated how political parties could serve as vehicles for organizing opposition and advancing competing visions of the nation.

The impact of Jefferson and Hamilton on party development extended beyond their lifetimes, as their ideologies became the foundation for future political movements. The Democratic-Republican Party evolved into the modern Democratic Party, while the Federalist Party's legacy influenced later conservative and Whig movements. Their contributions to American political culture—such as the importance of grassroots mobilization, the role of ideology in politics, and the necessity of organized opposition—remain central to the functioning of political parties today. In essence, Jefferson and Hamilton were not just leaders of their time but architects of the partisan framework that continues to shape American politics.

HIV/AIDS and Politics: Unraveling the Complex Intersection of Health and Power

You may want to see also

Structural Factors: Electoral systems, primaries, and institutional rules reinforcing party dominance

The roots of political parties in the United States are deeply intertwined with structural factors that have historically reinforced the dominance of the two major parties: the Democrats and the Republicans. Among these factors, the electoral system plays a pivotal role. The U.S. employs a winner-take-all system in most states for presidential elections, where the candidate who wins the popular vote in a state receives all of its Electoral College votes. This system inherently disadvantages third parties, as it creates a strong incentive for voters to support one of the two major parties to avoid "wasting" their vote. The duopoly of the Democratic and Republican parties is thus perpetuated, as smaller parties struggle to gain a foothold in a system designed to favor the largest contenders.

Primaries are another critical structural factor that reinforces party dominance. The primary election process, which determines each party's nominee for general elections, is controlled by the Democratic and Republican parties themselves. This control allows them to set rules that favor their own candidates and marginalize outsiders. For instance, ballot access requirements, filing fees, and signature collection mandates are often more stringent for third-party candidates, making it difficult for them to even appear on the ballot. Additionally, the scheduling and funding of debates are typically managed in ways that prioritize the major party candidates, further limiting the visibility and viability of third-party contenders.

Institutional rules within government also contribute to the dominance of the two major parties. The U.S. Congress, for example, operates under rules that disproportionately favor the majority party. The majority party controls committee assignments, legislative scheduling, and the agenda-setting process, effectively sidelining minority and third-party voices. This structural advantage ensures that the major parties remain the primary vehicles for political influence and policy-making, discouraging the emergence of viable alternatives. Similarly, campaign finance laws often provide greater funding and resources to candidates from the major parties, creating an uneven playing field that reinforces their dominance.

The interplay between electoral systems, primaries, and institutional rules creates a self-sustaining cycle of party dominance. The winner-take-all electoral system discourages voting for third parties, while primaries and institutional rules erect barriers to their participation and success. This structural framework has been instrumental in maintaining the two-party system, even as public dissatisfaction with both major parties has grown. Efforts to reform these structures, such as ranked-choice voting or open primaries, have faced significant resistance from the established parties, underscoring the entrenched nature of these factors in shaping the American political landscape.

In conclusion, the structural factors of electoral systems, primaries, and institutional rules have been fundamental in reinforcing the dominance of the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States. These mechanisms collectively create a political environment that marginalizes third parties and sustains the two-party system. Understanding these structural roots is essential for comprehending the enduring strength of the major parties and the challenges faced by those seeking to diversify the political landscape. Any meaningful reform aimed at fostering greater political pluralism must address these deeply embedded structural barriers.

The Rise and Reign of Political Machines in American History

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The roots of political parties in the U.S. trace back to the early years of the republic, emerging during George Washington's presidency. The first parties, the Federalists (led by Alexander Hamilton) and the Democratic-Republicans (led by Thomas Jefferson), formed in the 1790s over debates about the role of the federal government and the Constitution.

The two-party system solidified in the early 19th century due to the collapse of the Federalist Party and the rise of the Democratic Party (led by Andrew Jackson) and the Whig Party. By the 1850s, the modern Republican Party emerged, replacing the Whigs, and the Democratic and Republican Parties have since dominated American politics, largely due to electoral rules and winner-take-all systems.

Regional and ideological differences have been central to party formation. For example, the Civil War era saw parties divide over slavery, with Republicans opposing its expansion and Democrats often supporting it. Later, the Solid South shifted from Democratic to Republican as the parties realigned on civil rights and economic policies in the 20th century.

Third parties, such as the Progressive Party, the Populist Party, and the Libertarian Party, have influenced major parties by pushing issues like antitrust laws, labor rights, and smaller government into the mainstream. While rarely winning elections, they often force the dominant parties to address their platforms or risk losing voters.