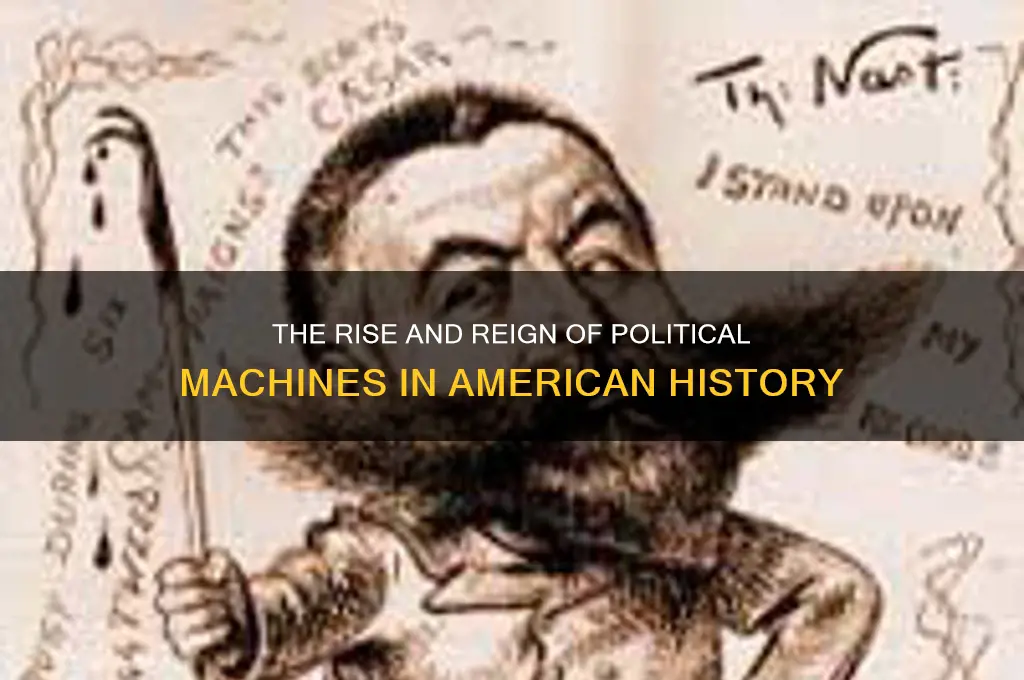

Political machines, which are informal organizations that control a political party and its nominations, were most dominant in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This era, often referred to as the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, saw the rise of powerful political bosses who wielded significant influence over local and state governments, particularly in urban areas. Cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston became strongholds for these machines, which operated by trading favors, jobs, and services for political support and votes. The dominance of political machines began to wane in the early 20th century due to reforms pushed by the Progressive movement, which aimed to increase transparency, reduce corruption, and democratize the political process. By the 1930s, many of these machines had significantly declined in power, though their legacy continues to shape American political history.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time Period | Late 19th to early 20th century (1870s–1930s) |

| Geographic Dominance | Primarily in urban areas of the United States (e.g., New York, Chicago) |

| Key Figures | Bosses like William Tweed (Tammany Hall), Richard J. Daley (Chicago) |

| Political Control | Local and municipal governments, often through patronage and corruption |

| Methods of Influence | Vote buying, patronage jobs, control of immigrant communities |

| Party Affiliation | Mostly associated with the Democratic Party in urban areas |

| Decline Factors | Progressive Era reforms, civil service reforms, anti-corruption campaigns |

| Legacy | Shaped modern urban politics, influenced party structures |

| Notable Examples | Tammany Hall (New York), Cook County Democratic Party (Chicago) |

| Impact on Elections | Controlled voter turnout through bloc voting and intimidation |

| Economic Influence | Controlled contracts, public works, and local businesses |

| Social Impact | Provided services to immigrants in exchange for political loyalty |

| Legal Response | Passage of laws like the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act (1883) |

| Modern Relevance | Echoes in machine-style politics still exist in some local governments |

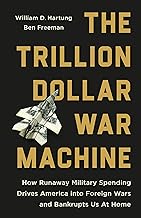

Explore related products

$13.99 $14.95

$32.25 $39

What You'll Learn

- Late 19th Century Urban Growth: Rapid city expansion fueled machine dominance in local politics

- Tammany Hall Influence: New York’s Tammany Hall exemplified machine power in the 1800s

- Boss-Led Systems: Political bosses controlled patronage, elections, and city resources

- Immigrant Dependence: Machines relied on immigrant votes in exchange for services

- Progressive Era Decline: Reforms in the early 1900s weakened machine dominance

Late 19th Century Urban Growth: Rapid city expansion fueled machine dominance in local politics

The late 19th century witnessed unprecedented urban growth in the United States, a phenomenon driven by industrialization, immigration, and the expansion of transportation networks. Cities like New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia experienced explosive population increases, often doubling or tripling in size within a few decades. This rapid urbanization created a chaotic and often unmanageable environment, with inadequate infrastructure, poor living conditions, and a diverse, often disenfranchised population. The sheer scale and speed of this growth overwhelmed existing local governments, which were ill-equipped to address the needs of their burgeoning populations. It was within this context that political machines found fertile ground to establish and consolidate their dominance.

Political machines, typically led by powerful bosses, emerged as de facto governing bodies in many cities. These organizations thrived by exploiting the inefficiencies and corruption of local governments and offering a semblance of order and services in exchange for political loyalty. Machines provided jobs, housing, and basic amenities to immigrants and the working class, who were often ignored by mainstream political institutions. In return, these constituents voted for machine-backed candidates, ensuring the machines' continued control over city politics. The machines' ability to deliver tangible benefits made them indispensable to the urban poor, who relied on them for survival in an unforgiving urban landscape.

The structure of local governments in the late 19th century further facilitated machine dominance. Many cities operated under weak mayor-council systems, where power was fragmented and accountability was minimal. This decentralization allowed machines to infiltrate various branches of government, from the police and courts to public works and welfare departments. By controlling these institutions, machines could manipulate elections, award contracts to loyalists, and suppress opposition. The lack of transparency and oversight in municipal governance enabled machines to operate with impunity, often blurring the lines between public service and private gain.

Rapid urban growth also created a highly stratified and fragmented social environment, which machines exploited to their advantage. Immigrants, particularly those from non-English-speaking backgrounds, faced significant barriers to political participation, including language, cultural differences, and discriminatory laws. Machines capitalized on this vulnerability by acting as intermediaries between these groups and the broader political system. They established precinct-level organizations, known as "ward heelers," who maintained close ties with local communities and ensured their loyalty through patronage and favors. This grassroots network was crucial in mobilizing voters and maintaining the machines' grip on power.

Finally, the economic opportunities presented by urban expansion provided machines with ample resources to sustain their operations. The construction boom, fueled by the need for housing, transportation, and public utilities, generated lucrative contracts and kickbacks. Machines controlled the allocation of these contracts, enriching themselves and their supporters while solidifying their political influence. Additionally, the growth of industries and businesses in cities created a dependent relationship between corporate interests and political machines, as both relied on each other for favors and protection. This symbiotic relationship further entrenched machine dominance in local politics, making them nearly invincible until reforms and public backlash began to challenge their authority in the early 20th century.

Clermont Political Races: Winners and Key Takeaways from the Election

You may want to see also

Tammany Hall Influence: New York’s Tammany Hall exemplified machine power in the 1800s

Tammany Hall, a powerful Democratic political machine, dominated New York City’s political landscape throughout much of the 1800s, embodying the era when political machines held significant sway in American urban centers. Established in 1789 as a social and political organization, Tammany Hall evolved into a formidable force by the mid-19th century, leveraging its influence to control elections, distribute patronage, and shape public policy. Its dominance was rooted in its ability to mobilize immigrant communities, particularly Irish Catholics, who were often marginalized by the city’s Protestant elite. By offering these groups tangible benefits—such as jobs, housing, and legal assistance—Tammany Hall secured their loyalty, creating a robust voter base that ensured its political supremacy.

The machine’s power was exemplified through its control of local and state offices, often achieved through a combination of voter turnout, election fraud, and strategic alliances. Bosses like William "Boss" Tweed in the 1860s and 1870s epitomized Tammany Hall’s influence, using their positions to amass wealth and consolidate power. Tweed, in particular, oversaw a vast network of corruption, including embezzlement of public funds and rigged contracts, which enriched both himself and his associates. Despite occasional scandals and public backlash, Tammany Hall’s ability to deliver services and maintain its political machine kept it firmly in control of New York City’s politics for decades.

Tammany Hall’s influence extended beyond local politics, impacting national elections and policy decisions. By delivering New York’s electoral votes, Tammany bosses played a crucial role in presidential elections, particularly within the Democratic Party. Their ability to mobilize voters and ensure electoral victories made them indispensable to national politicians seeking office. This influence was particularly evident during the Gilded Age, when the machine’s power peaked, and its leaders became kingmakers in both state and federal politics.

The machine’s success was also tied to its adaptability and responsiveness to the needs of its constituents. As waves of immigrants arrived in New York City, Tammany Hall adjusted its strategies to incorporate these new communities into its political network. For example, the machine cultivated relationships with Italian, Jewish, and other immigrant groups in the late 1800s, ensuring its continued relevance as the city’s demographics shifted. This ability to evolve and cater to diverse populations was a key factor in Tammany Hall’s prolonged dominance.

Despite its eventual decline in the early 20th century due to reform movements and changing political landscapes, Tammany Hall’s legacy as a quintessential political machine remains unparalleled. Its influence in the 1800s demonstrated the power of patronage, grassroots organization, and strategic alliances in shaping urban politics. Tammany Hall’s rise and reign in New York City serve as a prime example of how political machines operated during their heyday, leaving an indelible mark on American political history.

Exploring Russia's Political Landscape: Key Parties and Their Influence

You may want to see also

Boss-Led Systems: Political bosses controlled patronage, elections, and city resources

The era of boss-led political machines was a defining period in American urban politics, particularly from the late 19th to the early 20th century. During this time, political bosses wielded immense power, controlling patronage, elections, and city resources with an iron grip. These bosses were often the heads of political parties in major cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston, and their influence extended into every facet of local governance. Patronage was a cornerstone of their power, as they distributed government jobs, contracts, and favors to loyal supporters, creating a network of dependency that ensured their political dominance.

Political bosses thrived in an environment where voting rights were expanding but regulatory oversight was minimal. They exploited the lack of transparency and accountability in city governments to manipulate elections through voter fraud, intimidation, and bribery. "Repeaters" who voted multiple times, "floaters" who voted in multiple precincts, and "dead souls" who voted despite being deceased were common tactics used to secure victories for machine-backed candidates. Bosses like William Tweed in New York and Richard J. Daley in Chicago mastered these methods, ensuring their candidates won elections and maintained control over city councils, mayoralties, and other key offices.

Control over city resources was another critical aspect of boss-led systems. Political machines often directed public funds and projects to benefit their supporters and consolidate power. Infrastructure projects, such as road construction, public transportation, and sanitation, were awarded to businesses aligned with the machine, creating a cycle of economic dependency. Bosses also used their influence to shape urban development, often prioritizing projects that benefited their political and financial allies rather than the broader public. This control over resources allowed them to maintain a stranglehold on city politics and ensure their continued dominance.

The social and economic conditions of the time played a significant role in the rise of political machines. Rapid urbanization and immigration created diverse, often impoverished populations that were vulnerable to the machines' promises of jobs, housing, and protection. Bosses positioned themselves as benefactors, providing services that the government often neglected, such as food, coal, and even legal assistance. This clientelistic relationship fostered loyalty among constituents, who relied on the machines for their basic needs. In exchange, they provided votes and political support, perpetuating the bosses' power.

Despite their often corrupt practices, boss-led systems were not without their defenders. Supporters argued that political machines provided stability and efficiency in rapidly growing cities, cutting through bureaucratic red tape to get things done. They also claimed that machines represented the interests of marginalized groups, such as immigrants and the working class, who were often excluded from mainstream politics. However, the widespread corruption and abuse of power eventually led to public backlash and reforms. The Progressive Era, which began in the late 19th century and gained momentum in the early 20th century, sought to dismantle political machines through measures like civil service reforms, direct primaries, and stricter election laws. By the mid-20th century, the dominance of boss-led systems had significantly declined, though their legacy continues to influence urban politics today.

Political Parties' Role in Judicial Elections: Influence and Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Immigrant Dependence: Machines relied on immigrant votes in exchange for services

The dominance of political machines in American urban centers during the late 19th and early 20th centuries was deeply intertwined with their reliance on immigrant communities. These machines, often associated with major political parties, thrived in cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston, where waves of immigrants from Europe and other parts of the world were settling. The machines recognized the political potential of these newcomers, who often faced language barriers, discrimination, and economic hardship. By offering essential services and support, the machines secured the loyalty and votes of immigrants, creating a symbiotic relationship that bolstered their political power.

Immigrants, in turn, depended on these political machines for assistance in navigating the complexities of American life. Machines provided jobs, housing, legal aid, and even English lessons, acting as a bridge between immigrants and the broader society. For example, Tammany Hall in New York City became infamous for its ability to mobilize Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants by offering them patronage jobs, such as positions in the police force or sanitation department. In exchange, immigrants were expected to vote for machine-backed candidates, ensuring the machine's continued dominance in local and state politics.

The services provided by political machines were not merely acts of charity but strategic investments. By securing immigrant votes, machines could control key electoral districts, influence legislation, and maintain their grip on power. This system was particularly effective because immigrants often lacked alternative sources of support. In an era before robust social welfare programs, the machines filled a critical void, making them indispensable to immigrant communities. This dependence was further reinforced through cultural and social ties, as machine bosses often shared the same ethnic backgrounds as the immigrants they served, fostering a sense of trust and loyalty.

However, this reliance on immigrant votes also had darker implications. Machines frequently exploited immigrants' vulnerabilities, using intimidation or fraud to ensure compliance. For instance, immigrants might be threatened with deportation or loss of employment if they failed to vote as instructed. Additionally, the machines' focus on short-term political gains often came at the expense of long-term community development, as resources were diverted to maintain the machine's power rather than address systemic issues like poverty or education.

Despite these criticisms, the immigrant dependence on political machines played a significant role in shaping American politics during their heyday. It highlighted the challenges faced by immigrants in integrating into American society and the opportunistic nature of political organizations in leveraging these challenges for their benefit. The decline of political machines in the mid-20th century, due to reforms and changing political landscapes, marked the end of this era, but their legacy in urban politics and immigrant communities remains a critical chapter in American history.

Strengthening Democracy: The Vital Role of Political Parties in Governance

You may want to see also

Progressive Era Decline: Reforms in the early 1900s weakened machine dominance

The Progressive Era, spanning from the late 19th to the early 20th century, marked a significant turning point in American politics, particularly in the decline of political machines that had dominated urban centers. Political machines, such as Tammany Hall in New York City, had thrived by controlling access to government jobs, services, and favors in exchange for votes and loyalty. However, by the early 1900s, a wave of reform-minded activists and politicians sought to dismantle these corrupt systems, leading to a substantial weakening of machine dominance.

One of the key reforms that undermined political machines was the introduction of the secret ballot. Prior to this reform, voting was often a public act, allowing machine bosses to monitor how individuals voted and coerce them into supporting machine candidates. The secret ballot, adopted widely in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ensured voter privacy and reduced the ability of machines to intimidate or bribe voters. This reform shifted power away from machine bosses and toward individual voters, making it harder for machines to maintain their grip on local politics.

Another critical reform was the implementation of civil service systems, which replaced the spoils system that had long been a cornerstone of machine politics. Under the spoils system, government jobs were awarded to political supporters rather than based on merit. Progressive reformers pushed for civil service reforms that required competitive exams and qualifications for government positions. This change not only reduced patronage, a primary tool of machine control, but also professionalized government, making it less susceptible to machine influence.

Direct primary elections also played a pivotal role in weakening political machines. Before the Progressive Era, party bosses handpicked candidates through closed caucuses and conventions, ensuring their loyalists dominated the political landscape. The introduction of direct primaries allowed voters to choose candidates themselves, bypassing machine-controlled processes. This reform democratized the nomination process and empowered ordinary citizens, further eroding the machines' ability to control political outcomes.

Additionally, the rise of investigative journalism, often referred to as muckraking, exposed the corruption and inefficiencies of political machines. Journalists like Lincoln Steffens and Ida Tarbell published exposés that galvanized public opinion against machine politics. Their work, combined with the efforts of reform organizations like the National Municipal League, pressured governments to adopt transparency and accountability measures, making it harder for machines to operate in the shadows.

Finally, the Progressive Era saw the enactment of laws aimed directly at curbing machine power. For example, the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913 established the direct election of U.S. Senators, removing the selection process from state legislatures, which were often controlled by machines. At the local level, cities adopted council-manager forms of government, reducing the influence of machine-dominated mayors and city councils. These legal and structural changes collectively contributed to the decline of political machines as dominant forces in American politics.

In conclusion, the Progressive Era reforms of the early 1900s systematically dismantled the mechanisms that sustained political machines. Through the secret ballot, civil service reforms, direct primaries, investigative journalism, and legal changes, reformers shifted power from machine bosses to the public. While political machines did not disappear entirely, their dominance was significantly weakened, paving the way for a more transparent and accountable political system.

How to Unregister from a Political Party: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political machines were most dominant in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (roughly 1870s to 1920s).

Cities like New York (Tammany Hall), Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia were notorious for their powerful political machines that controlled local and state politics.

The rise of political machines was fueled by rapid urbanization, immigration, corruption, and the need for patronage jobs, as well as weak regulatory oversight of elections and governance.

Political machines declined due to Progressive Era reforms, such as civil service laws, direct primaries, and anti-corruption measures, which reduced their ability to control elections and distribute patronage.