Lobbies in politics refer to organized groups or individuals who attempt to influence legislation, policies, or government decisions in favor of their specific interests. These groups often consist of corporations, non-profit organizations, trade associations, or advocacy coalitions that employ various strategies, such as direct communication with lawmakers, campaign contributions, public awareness campaigns, and research dissemination, to shape political outcomes. While lobbies can provide valuable expertise and represent diverse perspectives, they are also frequently criticized for potentially distorting democratic processes by prioritizing narrow interests over the broader public good. Understanding the role and impact of lobbies is essential for comprehending the dynamics of modern political systems and the interplay between power, influence, and governance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Organized groups or individuals who attempt to influence political decisions and policy-making. |

| Purpose | Advocate for specific interests, policies, or legislation. |

| Methods | Direct lobbying (meeting policymakers), indirect lobbying (public campaigns), grassroots lobbying (mobilizing public support). |

| Actors | Corporations, NGOs, trade associations, labor unions, advocacy groups, individuals. |

| Funding | Often funded by memberships, donations, or corporate sponsors. |

| Transparency | Varies by country; some require registration and disclosure of activities. |

| Regulation | Governed by lobbying laws (e.g., Lobbying Disclosure Act in the U.S.). |

| Ethical Concerns | Potential for undue influence, corruption, or favoritism. |

| Impact | Can shape legislation, regulatory decisions, and public policy outcomes. |

| Global Presence | Exists in democratic and authoritarian regimes, though practices differ. |

| Examples | NRA (U.S.), Big Pharma lobbying, environmental advocacy groups. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Lobbying Definition: Paid or volunteer efforts to influence government decisions on policies, laws, or regulations

- Types of Lobbies: Corporate, public interest, labor unions, and single-issue advocacy groups

- Lobbying Tactics: Direct communication, grassroots campaigns, campaign contributions, and media influence

- Regulation & Ethics: Laws governing transparency, disclosure, and limits on lobbying activities

- Impact on Policy: How lobbies shape legislation, public opinion, and political priorities

Lobbying Definition: Paid or volunteer efforts to influence government decisions on policies, laws, or regulations

Lobbying is the strategic art of persuasion in politics, where individuals or groups advocate for specific causes, aiming to shape the very laws that govern society. This practice, often shrouded in controversy, is a powerful tool for those seeking to influence government decisions. At its core, lobbying is about amplifying voices, ensuring that particular interests are heard in the halls of power.

The Mechanics of Lobbying:

Imagine a scenario where a group of environmental activists wants to push for stricter regulations on industrial pollution. They might employ various tactics: organizing public protests to capture media attention, drafting detailed policy proposals, or arranging private meetings with lawmakers. These efforts, whether funded by donations or driven by volunteer passion, are all acts of lobbying. It's a process that can be as simple as a grassroots movement or as complex as a multi-million-dollar campaign led by professional lobbyists.

A Spectrum of Influence:

Lobbying exists on a spectrum, ranging from local community efforts to global corporate strategies. For instance, a neighborhood association might lobby the city council to install traffic-calming measures, while a tech giant could employ an army of lobbyists to shape national data privacy laws. The common thread is the intent to sway government decisions, be it at the local, state, or federal level. This activity is not inherently negative; it's a democratic process that allows diverse interests to be represented. However, the potential for abuse is real, especially when powerful entities wield disproportionate influence.

Navigating the Ethical Landscape:

The ethical dimensions of lobbying are complex. On one hand, it provides a platform for marginalized groups to advocate for their rights. For instance, civil rights organizations have historically lobbied for legislative changes to combat discrimination. On the other hand, concerns arise when lobbying efforts are opaque or when special interests undermine the public good. Transparency is key; many countries have implemented lobbying disclosure laws to ensure that the public can scrutinize these activities. For instance, the U.S. Lobbying Disclosure Act requires lobbyists to register and report their activities, providing a measure of accountability.

Practical Considerations:

For those considering engaging in lobbying, understanding the legal framework is essential. In the U.S., the process typically involves registering as a lobbyist, which requires disclosing clients, issues, and expenditures. This transparency is designed to prevent clandestine influence-peddling. Additionally, building relationships with policymakers is crucial. Effective lobbyists often have a deep understanding of the political landscape, knowing which lawmakers are receptive to specific causes. This knowledge can be gained through research, networking, and, in some cases, hiring experienced lobbying firms. While lobbying can be a powerful tool for change, it requires a strategic approach, combining passion with a pragmatic understanding of the political system.

Understanding Political Institutionalism: Frameworks, Functions, and Societal Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Types of Lobbies: Corporate, public interest, labor unions, and single-issue advocacy groups

Corporate lobbies wield significant influence by leveraging financial resources and market power to shape policies favorable to their industries. Consider the pharmaceutical sector, where companies spend billions annually on lobbying to influence drug pricing regulations, patent laws, and healthcare policies. For instance, in 2022, the pharmaceutical industry spent over $300 million on lobbying efforts in the U.S. alone. This type of lobbying often involves direct meetings with lawmakers, funding political campaigns, and commissioning studies that support their positions. While critics argue this creates regulatory capture, proponents claim it ensures business perspectives are considered in policy-making. The key takeaway? Corporate lobbies are a double-edged sword—driving economic growth but risking unequal representation in governance.

Public interest lobbies, in contrast, operate with a mission to advocate for broader societal benefits rather than private gain. Organizations like the Sierra Club or the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) exemplify this category, pushing for environmental protection, civil rights, and social justice. Their strategies include grassroots mobilization, public awareness campaigns, and legal challenges. Unlike corporate lobbies, their funding often comes from individual donations and grants, which can limit their financial clout but enhances their moral authority. A practical tip for engaging with public interest groups: research their track record and transparency to ensure alignment with your values. These lobbies serve as a critical counterbalance to corporate influence, amplifying voices that might otherwise be overlooked.

Labor unions represent a distinct type of lobbying, focusing on workers’ rights, wages, and workplace conditions. Historically, unions like the AFL-CIO have negotiated collective bargaining agreements and lobbied for labor-friendly legislation, such as minimum wage increases and workplace safety standards. Their strength lies in collective action—strikes, protests, and member mobilization—coupled with direct advocacy in legislative arenas. However, declining union membership in recent decades has weakened their influence, particularly in right-to-work states. For individuals, joining a union can provide protections and bargaining power, but it’s essential to understand the specific benefits and obligations of membership. Labor unions remain a vital force for economic equity, though their effectiveness depends on active participation and strategic adaptation.

Single-issue advocacy groups are laser-focused on specific causes, such as gun control, abortion rights, or animal welfare. The National Rifle Association (NRA) and Planned Parenthood are prime examples, each rallying supporters and lobbying lawmakers around their core issues. These groups often employ emotional appeals, targeted campaigns, and grassroots organizing to drive their agendas. Their narrow focus allows for deep expertise and passionate engagement but can limit their influence on broader policy discussions. A cautionary note: single-issue groups may prioritize their cause at the expense of related issues, potentially leading to unintended consequences. For advocates, aligning with these groups can be impactful, but it’s crucial to consider the broader policy landscape to avoid siloed thinking.

Stop Political Robotexts: Effective Strategies to Regain Your Privacy

You may want to see also

Lobbying Tactics: Direct communication, grassroots campaigns, campaign contributions, and media influence

Lobbying is the act of attempting to influence decisions made by government officials, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies. At its core, lobbying involves strategic communication and persuasion, employing various tactics to shape policy outcomes. Among these, four stand out for their effectiveness and prevalence: direct communication, grassroots campaigns, campaign contributions, and media influence. Each tactic serves a distinct purpose, catering to different stages of the political process and leveraging unique strengths to achieve advocacy goals.

Direct communication is the most straightforward lobbying tactic, involving face-to-face meetings, phone calls, or personalized letters between lobbyists and policymakers. This method thrives on building relationships and providing expert insights. For instance, a healthcare lobbyist might meet with a senator to explain the technical implications of a proposed bill on medical device regulations. The key here is personalization—tailoring the message to the official’s priorities, concerns, or constituency needs. However, this tactic requires access, which smaller organizations may struggle to secure. To maximize effectiveness, lobbyists should prepare concise, data-driven arguments and follow up with written summaries to reinforce key points.

Grassroots campaigns, in contrast, mobilize the public to advocate on behalf of an issue. This tactic shifts the focus from individual policymakers to their constituents, creating a groundswell of support that politicians cannot ignore. For example, environmental groups often organize petitions, town hall meetings, and social media campaigns to pressure lawmakers into supporting climate legislation. The strength of grassroots efforts lies in their ability to demonstrate broad public engagement. However, success depends on clear messaging and sustained participation. Organizers should use digital tools to streamline participation, such as providing pre-written emails or call scripts, and set measurable goals, like securing a specific number of signatures or calls to congressional offices.

Campaign contributions are a more transactional tactic, leveraging financial support to gain access and influence. While critics often associate this method with corruption, it is a legal and widespread practice in many political systems. For instance, corporations and interest groups frequently donate to political campaigns or PACs (Political Action Committees) to align themselves with candidates who share their policy goals. The challenge is ensuring transparency and compliance with campaign finance laws. Lobbyists should focus on building long-term relationships rather than expecting immediate policy favors, and organizations must carefully track contributions to avoid legal pitfalls.

Media influence rounds out the toolkit, using press releases, op-eds, and social media to shape public perception and, by extension, political decisions. This tactic is particularly powerful in the digital age, where viral stories can rapidly shift the narrative. For example, a tech company might publish a series of articles highlighting the economic benefits of relaxed data privacy regulations. The goal is to frame the issue in a way that resonates with both the public and policymakers. However, media campaigns require careful planning to avoid backfiring. Lobbyists should monitor public sentiment, fact-check all claims, and be prepared to respond to counterarguments.

Together, these tactics form a multifaceted approach to lobbying, each addressing different aspects of the political landscape. Direct communication builds personal connections, grassroots campaigns harness public pressure, campaign contributions secure access, and media influence shapes the narrative. By strategically combining these methods, lobbyists can effectively navigate the complexities of policymaking and advance their agendas. The key is adaptability—tailoring the approach to the specific issue, audience, and political climate.

Is Anarchism a Political Ideology? Exploring Its Core Principles and Relevance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Regulation & Ethics: Laws governing transparency, disclosure, and limits on lobbying activities

Lobbying, while a cornerstone of democratic engagement, carries inherent risks of undue influence and opacity. To mitigate these risks, regulatory frameworks have emerged globally, focusing on transparency, disclosure, and activity limits. These laws aim to balance the right to petition governments with the need to prevent corruption and ensure public trust. For instance, the United States’ Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA) of 1995 mandates that lobbyists register with Congress and report their activities quarterly, including expenditures and clients. Similarly, the European Union’s Transparency Register requires organizations to disclose their lobbying budgets, targets, and activities, though compliance remains voluntary, highlighting the variability in enforcement across jurisdictions.

Transparency laws serve as the first line of defense against clandestine influence. By requiring lobbyists to disclose their activities, these regulations enable public scrutiny and accountability. However, the effectiveness of such laws hinges on their specificity and enforceability. For example, Canada’s *Lobbying Act* not only mandates registration but also imposes a five-year ban on lobbying activities for former public office holders, a measure designed to curb the "revolving door" phenomenon. In contrast, some countries, like India, lack comprehensive lobbying regulations, leaving the process vulnerable to opacity and abuse. This disparity underscores the need for global standards that adapt to local contexts while maintaining rigor.

Disclosure requirements, while critical, are only as effective as the data they generate. Vague or incomplete reporting undermines their purpose, necessitating clear guidelines and penalties for non-compliance. The United Kingdom’s Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists, for instance, imposes fines for failure to register or submit accurate returns. Yet, critics argue that the registrar’s scope is too narrow, excluding in-house lobbyists and those working for charities, thereby creating loopholes. To address this, some jurisdictions, like France, have adopted digital platforms where lobbying interactions with public officials are logged in real-time, enhancing traceability and reducing manipulation.

Limits on lobbying activities, such as spending caps or restrictions on gifts to officials, further safeguard against disproportionate influence. For example, the U.S. places a $50 limit on gifts from lobbyists to federal officials, while Ireland prohibits gifts altogether. However, such measures must be carefully calibrated to avoid stifling legitimate advocacy. A comparative analysis reveals that countries with stricter limits often pair them with robust funding mechanisms for public interest groups, ensuring a level playing field. For instance, Germany’s Party Law provides public funding to political parties, reducing their reliance on private donors and, by extension, lobbying pressures.

Ultimately, the regulation of lobbying is a delicate balance between fostering democratic participation and preventing systemic corruption. While transparency, disclosure, and activity limits form the backbone of ethical lobbying, their success depends on robust enforcement, international cooperation, and public awareness. Policymakers must continually reassess these frameworks to address emerging challenges, such as the rise of digital lobbying and the globalization of influence networks. By doing so, they can ensure that lobbying remains a tool for constructive engagement rather than a vehicle for undue power.

Understanding Armchair Politics: Passive Engagement in Today's Political Landscape

You may want to see also

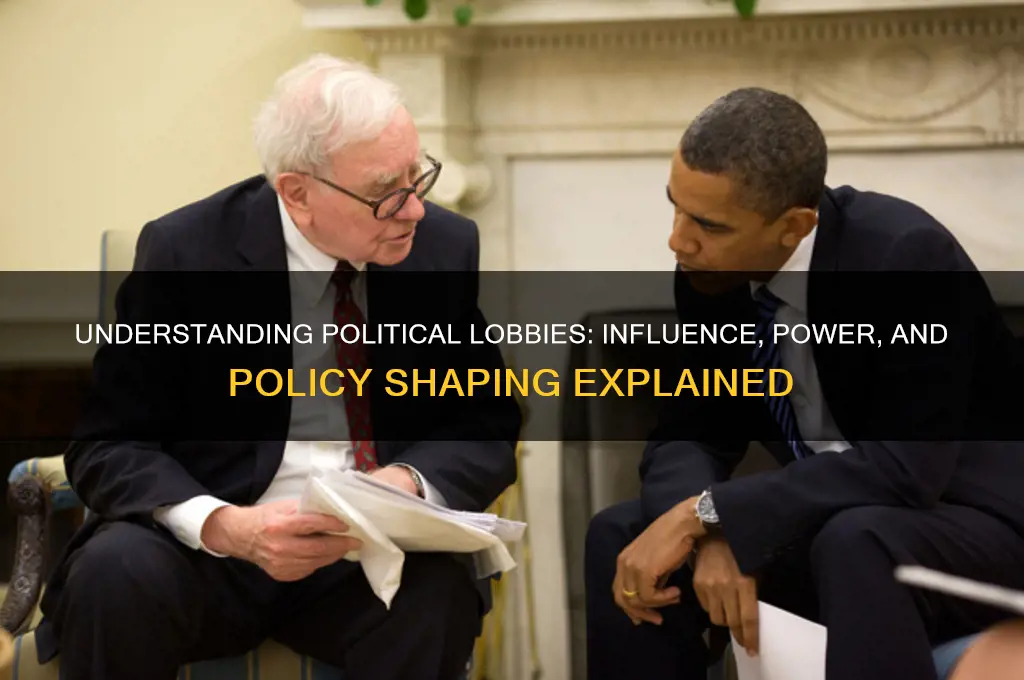

Impact on Policy: How lobbies shape legislation, public opinion, and political priorities

Lobbies wield significant influence over policy by strategically shaping legislation, molding public opinion, and redefining political priorities. Consider the pharmaceutical industry, which spent over $300 million on lobbying in 2022 alone. This investment often translates into favorable policies, such as extended drug patents or relaxed FDA regulations, directly impacting healthcare costs and accessibility. By deploying experts, funding research, and drafting model legislation, lobbies like these embed their interests into the legislative process, often before the public or opposing groups can mobilize a response.

To understand how lobbies shape public opinion, examine their use of media campaigns and grassroots mobilization. For instance, the National Rifle Association (NRA) has long framed gun ownership as a fundamental right, leveraging emotional narratives and targeted messaging to sway public sentiment. Through social media, op-eds, and community events, lobbies amplify their messages, creating an echo chamber that influences voter perceptions and, ultimately, the political discourse. This strategic communication often outpaces counter-narratives, making it difficult for alternative viewpoints to gain traction.

A closer look at political priorities reveals how lobbies redirect government focus. Environmental groups, for example, have successfully pushed climate change to the forefront of policy agendas by organizing mass protests, publishing impactful studies, and lobbying for specific bills like the Green New Deal. Conversely, fossil fuel lobbies have historically diverted attention from renewable energy by emphasizing job creation and energy independence. This tug-of-war illustrates how lobbies not only advocate for their interests but also determine which issues receive funding, attention, and legislative action.

Practical steps to mitigate undue lobby influence include increasing transparency and imposing stricter ethics rules. Citizens can demand real-time disclosure of lobbying activities, as seen in the European Union’s Transparency Register, which tracks meetings between lobbyists and policymakers. Additionally, policymakers should adopt "cooling-off periods" to prevent officials from immediately transitioning into lobbying roles. By empowering watchdog organizations and educating the public on lobbying tactics, societies can ensure that policy decisions serve the greater good rather than narrow interests.

In conclusion, lobbies are not inherently problematic; their impact depends on how their influence is regulated and balanced. While they provide valuable expertise and represent diverse interests, unchecked lobbying can distort policy outcomes. By understanding their strategies and implementing safeguards, stakeholders can foster a more equitable and responsive political system. The challenge lies in preserving the right to advocate while preventing the hijacking of public policy for private gain.

Mastering Political Writing: Crafting Compelling and Impactful Political Content

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Lobbies in politics are organized groups or individuals who attempt to influence government decisions, policies, or legislation in favor of their specific interests or causes.

Lobbies operate by engaging in activities such as meeting with lawmakers, funding campaigns, providing research or data, and mobilizing public support to advocate for their desired outcomes.

No, lobbies can be formed by a variety of entities, including corporations, labor unions, non-profit organizations, advocacy groups, and even individuals with shared interests.

Yes, lobbying is legal in most democratic systems, provided it is conducted transparently and within the boundaries of the law, such as registering as a lobbyist and disclosing activities.

Lobbying involves legitimate advocacy and persuasion to influence policy, while bribery involves offering or accepting something of value in exchange for specific actions or favors, which is illegal.