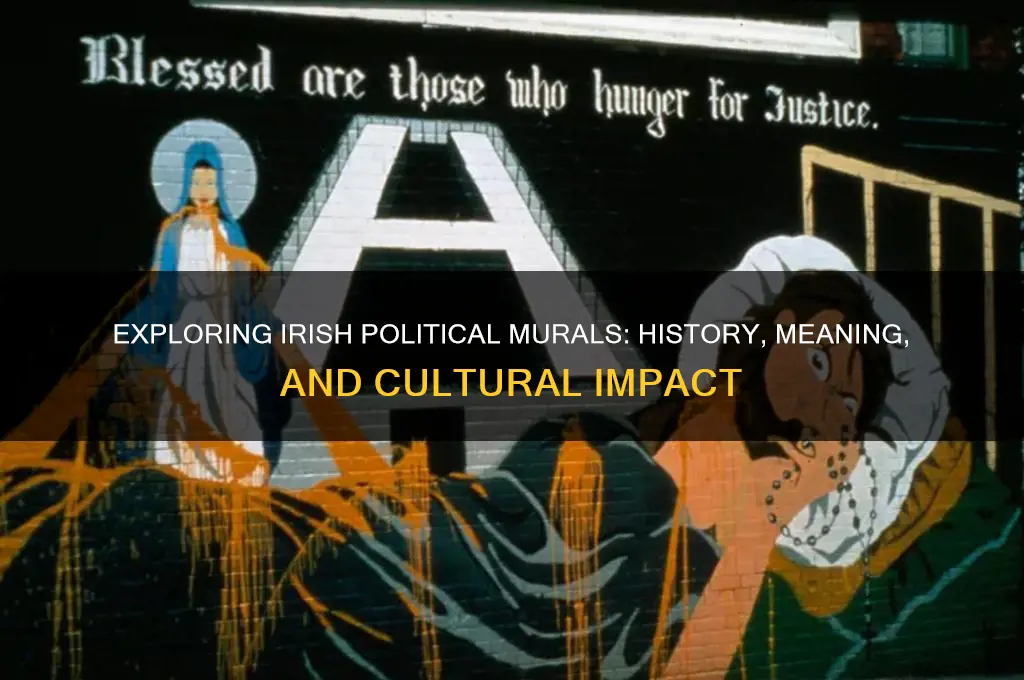

Irish political murals are a powerful and enduring form of public art that reflect the complex history, cultural identity, and political divisions of Northern Ireland. Rooted in the Troubles, a period of ethno-nationalist conflict spanning from the late 1960s to the 1990s, these murals serve as visual narratives of community beliefs, allegiances, and struggles. Painted predominantly in working-class neighborhoods, they often depict themes of resistance, remembrance, and pride, with Unionist murals celebrating British identity and loyalty to the Crown, while Nationalist murals emphasize Irish republicanism and the fight for a united Ireland. Beyond their political messages, these murals have become a significant cultural and tourist attraction, offering insight into the region’s past and ongoing dialogue about its future.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Visual representations of political, religious, or cultural beliefs, often painted on walls in Northern Ireland and other parts of Ireland. |

| Historical Context | Rooted in the Troubles (1968–1998), a period of conflict between Nationalists (mainly Catholic) and Unionists (mainly Protestant). |

| Themes | Nationalism, Republicanism, Loyalism, peace, resistance, historical events, and commemorations of key figures or events. |

| Locations | Predominantly in working-class neighborhoods of Belfast, Derry, and other towns in Northern Ireland. |

| Symbolism | Often includes flags (e.g., Irish Tricolor, Union Jack), emblems (e.g., shamrock, crown), and iconic figures (e.g., Bobby Sands, King William III). |

| Styles | Bold, colorful, and large-scale, often using stencils, freehand painting, or mosaics. |

| Purpose | To assert identity, commemorate sacrifices, intimidate opponents, or promote political agendas. |

| Artists | Both professional and amateur artists, often anonymous or part of community groups. |

| Legality | Some murals are commissioned by local councils, while others are unauthorized and may be considered illegal. |

| Evolution | Post-Troubles, many murals have shifted from divisive messages to themes of peace, reconciliation, and cultural pride. |

| Tourism | Have become a significant tourist attraction, with guided tours highlighting their historical and cultural significance. |

| Preservation | Efforts are made to preserve murals as part of Ireland's cultural heritage, though many are temporary and subject to weathering or removal. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Context: Murals reflect Ireland's political history, including conflicts and key events like The Troubles

- Symbolism: Common symbols include flags, emblems, and figures representing nationalism or unionism

- Locations: Murals are often found in Belfast, Derry, and other politically significant areas

- Artists and Communities: Local artists and communities create murals to express identity and resistance

- Evolution: Murals have shifted from conflict-focused to themes of peace and reconciliation

Historical Context: Murals reflect Ireland's political history, including conflicts and key events like The Troubles

Irish political murals are not mere decorations; they are visual narratives etched into the walls of history, reflecting the island's tumultuous past. These murals, often found in Northern Ireland, serve as a powerful medium to communicate political ideologies, commemorate key events, and honor figures central to the region's struggles. The Troubles, a period of intense conflict from the late 1960s to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, dominate the themes of these murals, showcasing the deep divisions between unionists (who wish to remain part of the United Kingdom) and nationalists (who seek a united Ireland). Each mural is a snapshot of a specific moment, a declaration of identity, and a reminder of the sacrifices made during this era.

To understand the significance of these murals, consider their placement and symbolism. In unionist areas, murals often depict British symbols like the Union Jack, the Crown, and loyalist paramilitaries, reinforcing their allegiance to the UK. Nationalist murals, on the other hand, frequently feature the Irish tricolor, republican figures like Bobby Sands, and scenes from the Easter Rising of 1916. These images are not random; they are carefully chosen to evoke emotion and solidarity among viewers. For instance, a mural of Bobby Sands, who died during a hunger strike in 1981, serves as a poignant reminder of the lengths to which individuals went to fight for their cause.

Analyzing these murals reveals their dual role as both historical documents and tools of political expression. They are not static; they evolve with the political climate. During the height of The Troubles, murals were often more confrontational, depicting armed figures and slogans calling for resistance. Post-Good Friday Agreement, many murals shifted to themes of peace, reconciliation, and cultural pride, reflecting the desire for a new chapter in Northern Ireland's history. This transformation underscores the murals' adaptability and their role in shaping public memory.

For those interested in exploring these murals, a walking tour of Belfast’s Shankill Road (unionist) and Falls Road (nationalist) areas offers a vivid lesson in Ireland’s political history. Practical tips include wearing neutral clothing to avoid unintended associations and engaging with local guides who can provide context. Photography is generally allowed, but always ask permission when in residential areas. These murals are not just for locals; they are a global testament to the enduring power of art in political expression and historical preservation.

In conclusion, Irish political murals are more than art—they are living archives of a nation’s struggles and aspirations. By examining their themes, symbols, and evolution, one gains insight into the complexities of Ireland’s political history, particularly The Troubles. They challenge viewers to confront the past while inspiring reflection on the path toward peace. Whether you’re a historian, artist, or curious traveler, these murals offer a unique lens through which to understand Ireland’s enduring spirit.

Johnson's Stunning Political Reversal: Unraveling the Shocking Turnaround

You may want to see also

Symbolism: Common symbols include flags, emblems, and figures representing nationalism or unionism

Irish political murals are a powerful medium for conveying complex ideologies, often distilled into stark visual symbols. Among these, flags, emblems, and iconic figures stand out as the most immediate and recognizable markers of nationalism or unionism. The Union Jack and the Irish Tricolor, for instance, are not merely national flags but charged symbols of identity and allegiance. Their placement, size, and condition within a mural can subtly or overtly communicate dominance, resistance, or defiance. Similarly, emblems like the Red Hand of Ulster or the Celtic Harp transcend their historical origins to become shorthand for political and cultural affiliations. These symbols are not static; their meaning evolves with the socio-political climate, making them both timeless and deeply contextual.

Consider the instructive role of these symbols in shaping public perception. A mural featuring a figure like William of Orange, a hero of unionism, often includes the Orange Order’s purple banner or a sash, reinforcing Protestant and British identity. Conversely, nationalist murals might depict figures like Bobby Sands or Wolfe Tone alongside the Starry Plough, symbolizing Irish republicanism and socialist ideals. For those decoding these murals, understanding the symbolism is akin to reading a visual language. For example, a faded or torn flag in a mural might suggest decay or vulnerability, while a prominently placed emblem could signify resilience or triumph. Practical tip: When analyzing these murals, note the interplay between symbols—are they juxtaposed, overlapping, or isolated? This can reveal underlying tensions or alliances.

Persuasively, these symbols serve as rallying points for communities, fostering unity or division depending on the viewer’s perspective. Flags, in particular, are often depicted in ways that evoke emotional responses. A Union Jack painted in bold, unblemished colors on a unionist mural asserts strength and permanence, while a Tricolor surrounded by doves or olive branches in a nationalist mural might advocate for peace. Emblems, too, carry persuasive weight; the Crown, for instance, is frequently used in unionist murals to emphasize loyalty to the British monarchy, while the Sunburst emblem in nationalist murals symbolizes a new dawn for an independent Ireland. Caution: Overlooking the emotional charge of these symbols can lead to misinterpretation of the mural’s intent.

Comparatively, the use of symbols in Irish political murals mirrors practices in other conflict zones, such as the Basque Country or Palestine, where flags and emblems similarly encode political narratives. However, the Irish context is unique in its layering of religious, historical, and cultural meanings. For instance, the color green in Irish murals is not just a national color but also a nod to Catholicism and the "Emerald Isle," while orange in unionist murals references both William of Orange and Protestantism. This dual or triple significance makes Irish mural symbolism particularly dense and multifaceted. Takeaway: To fully grasp the message, one must consider not just the symbol itself but its historical, religious, and cultural resonances.

Descriptively, the physical execution of these symbols adds another layer of meaning. A flag painted with precise, sharp lines conveys order and control, while a hand-painted, slightly uneven emblem might suggest grassroots authenticity. Figures representing nationalism or unionism are often depicted in heroic poses, their faces determined or solemn, surrounded by symbols that reinforce their narrative. For example, a mural of a unionist figure might be flanked by the Union Jack and a map of the six counties, emphasizing territorial claims, while a nationalist figure might stand before a map of a united Ireland, with the Tricolor billowing in the background. Practical tip: Pay attention to the texture and technique—are the symbols rendered with care, or are they hastily applied? This can indicate the community’s resources, urgency, or level of organization.

Understanding the Political Management Model: Strategies for Effective Governance

You may want to see also

Locations: Murals are often found in Belfast, Derry, and other politically significant areas

Irish political murals are most densely concentrated in Belfast and Derry, cities that served as epicenters of the Troubles. These locations were not chosen arbitrarily; they are deeply intertwined with the historical and political narratives of Northern Ireland. Belfast’s murals, for instance, are often found in working-class neighborhoods like the Falls Road (nationalist) and Shankill Road (unionist), where communities used walls as canvases to assert identity, commemorate sacrifice, and challenge opponents. Derry’s Bogside, another focal point, features murals that chronicle events like Bloody Sunday, embedding collective memory into the urban landscape. These areas remain politically charged, making them ideal sites for murals that continue to reflect ongoing tensions and aspirations.

To explore these murals effectively, start with a guided tour in Belfast, focusing on the Peace Wall, where new murals often replace older ones, symbolizing evolving relationships. In Derry, walk the Bogside Artists’ People’s Gallery, a series of 12 murals that narrate the city’s role in the Troubles. Practical tip: Wear comfortable shoes, as these areas are best experienced on foot. For deeper context, pair your visit with a stop at local community centers or museums, where residents often share personal stories tied to the murals. Avoid peak political anniversaries (e.g., July 12) if you prefer a quieter experience, as tensions can escalate during these times.

Comparatively, while Belfast and Derry dominate the mural landscape, smaller towns like Newry, Armagh, and Dungannon also host significant works, though fewer in number. These locations often feature murals tied to specific local events or figures, offering a more nuanced view of regional politics. For instance, Newry’s murals highlight its role as a border town, while Armagh’s focus on historical figures like Patrick Pearse underscores its republican legacy. To locate these lesser-known murals, consult local tourism offices or use apps like *MuralMap*, which provides GPS coordinates and historical context.

Persuasively, the placement of these murals is no accident—they are deliberately sited in areas of political significance to maximize visibility and impact. A mural on a gable wall in West Belfast isn’t just art; it’s a statement of resistance or solidarity, visible to thousands daily. This strategic positioning ensures that the messages endure, even as political landscapes shift. For visitors, understanding this intentionality deepens appreciation for the murals’ role as living documents of conflict and reconciliation. Engage with locals to uncover the stories behind specific murals; their insights often reveal layers of meaning missed by casual observers.

Finally, while Belfast and Derry are must-visits, don’t overlook the role of murals in cross-border locations like Louth or Monaghan, where works often address themes of unity or division across the Irish border. These areas offer a comparative perspective, highlighting how political murals function in both Northern Ireland and the Republic. For a comprehensive experience, plan a multi-day trip that includes both major cities and smaller towns, allowing you to trace the evolution of mural themes across regions. Practical tip: Bring a notebook to jot down mural details, as many lack explanatory plaques, and the stories behind them are worth preserving.

Navigating Workplace Politics: Strategies to Foster a Positive Work Environment

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Artists and Communities: Local artists and communities create murals to express identity and resistance

In Northern Ireland, local artists and communities have long turned to murals as a powerful medium to articulate their identity and resistance. These works are not mere decorations but deeply embedded cultural statements, often reflecting the complexities of the region’s political and social history. From the loyalist murals of Belfast’s Shankill Road to the republican artworks in Falls Road, each piece serves as a visual manifesto, reclaiming public space to tell stories that might otherwise be silenced. The very act of creation becomes an act of defiance, transforming walls into canvases of collective memory and aspiration.

Consider the process of mural creation as a collaborative endeavor. Local artists often work alongside community members, ensuring the artwork authentically represents shared experiences and values. For instance, in Derry’s Bogside, murals depicting the Bloody Sunday massacre were designed and painted by the Bogside Artists, a group deeply rooted in the community. This participatory approach not only fosters a sense of ownership but also amplifies the mural’s impact, turning it into a living monument that educates and inspires. Practical tip: Communities interested in starting a mural project should begin by holding open forums to gather ideas and ensure the design reflects diverse voices.

Analytically, these murals function as both mirrors and windows. They mirror the struggles, hopes, and identities of the communities that create them, while also offering outsiders a window into the lived realities of those communities. For example, murals in nationalist areas often feature symbols like the Irish tricolor or images of hunger striker Bobby Sands, asserting a distinct Irish identity in the face of British rule. In contrast, unionist murals might depict William of Orange or the Red Hand of Ulster, reinforcing loyalty to the British crown. This duality highlights how murals serve as tools of resistance, challenging dominant narratives and asserting alternative truths.

Persuasively, the enduring relevance of these murals lies in their ability to adapt to changing contexts. While many early murals were overtly political, reflecting the violence of the Troubles, contemporary works increasingly address broader social issues like peacebuilding, equality, and environmental justice. For instance, a recent mural in Belfast’s Gaeltacht Quarter celebrates the Irish language revival, a movement rooted in cultural resistance. This evolution demonstrates how murals remain a vital form of expression, capable of addressing both historical grievances and current challenges. Caution: Artists should be mindful of the potential for murals to polarize, ensuring their work promotes dialogue rather than division.

Descriptively, the physicality of these murals adds to their impact. Often spanning entire buildings, they dominate the urban landscape, impossible to ignore. The use of bold colors, larger-than-life figures, and symbolic imagery creates a visceral experience for viewers. In Ballymurphy, a mural commemorating the 1971 shootings features life-sized figures against a stark, monochromatic background, evoking a sense of loss and resilience. This scale and detail not only capture attention but also invite viewers to engage emotionally and intellectually with the narrative. Takeaway: When creating a mural, consider how size, color, and placement can enhance its message and emotional resonance.

Comparatively, Irish political murals share similarities with street art movements worldwide, from the revolutionary murals of Mexico to the protest art of Palestine. Yet, their specificity to the Northern Irish context—rooted in a centuries-old conflict over identity, sovereignty, and belonging—sets them apart. Unlike ephemeral graffiti, these murals are often commissioned and preserved, reflecting their status as cultural heritage. This unique blend of artistry, activism, and community engagement ensures their continued relevance, not just as historical artifacts but as living expressions of identity and resistance. Practical tip: Communities can document their mural projects through photography and oral histories to preserve their stories for future generations.

Understanding Politics: A Simple Definition for Everyday Life

You may want to see also

Evolution: Murals have shifted from conflict-focused to themes of peace and reconciliation

Irish political murals, once dominated by imagery of division and strife, now increasingly reflect themes of unity and healing. This transformation mirrors Northern Ireland’s broader journey from the Troubles to a fragile but enduring peace. Early murals in Belfast and Derry were starkly partisan, depicting paramilitary figures, political slogans, and symbols of resistance. Republican murals often featured the Irish tricolor and portraits of hunger strikers, while Loyalist murals showcased the Union Jack and references to the Ulster Volunteer Force. These works were not merely art but declarations of identity and defiance, etched onto walls in neighborhoods divided by peace lines.

The shift toward peace-oriented murals began in the late 1990s, coinciding with the Good Friday Agreement. Artists and communities started to reimagine walls as spaces for dialogue rather than division. For instance, the *International Wall* on Falls Road in Belfast, once a canvas for revolutionary icons, now includes murals celebrating global solidarity and local heroes like civil rights activist Betty Williams. Similarly, in Loyalist areas, depictions of King Billy on horseback have been joined by scenes of cross-community reconciliation and shared history. This evolution is not uniform; some murals still reflect lingering tensions, but the trend is unmistakable.

Creating a peace-themed mural requires more than artistic skill—it demands community engagement. Successful projects often involve workshops where residents, particularly young people, contribute ideas and designs. For example, the *Re-Imaging Communities* program has worked across Northern Ireland to replace paramilitary murals with art that fosters inclusivity. Practical tips for such initiatives include securing cross-community buy-in, using neutral symbols like doves or hands clasped across divides, and incorporating local history in ways that respect all narratives. Funding often comes from government grants or NGOs, but grassroots support is essential for longevity.

Comparing old and new murals reveals a shift from exclusion to embrace. Where once a wall might have warned “You are now entering Loyalist territory,” it now might display a quote from Seamus Heaney or a depiction of children from both traditions playing together. This change is not just symbolic; it reflects a generational shift. Younger artists, unburdened by the trauma of the Troubles, are more likely to explore themes of hope and shared futures. However, this evolution is fragile. Murals remain contested spaces, and their preservation or alteration can reignite old debates.

The takeaway is clear: murals are not static artifacts but living narratives that adapt to societal change. Their evolution from conflict to reconciliation demonstrates art’s power to heal and unite. For visitors or researchers, understanding this transformation requires looking beyond the paint to the stories behind it. Engage with local guides, read the accompanying plaques, and listen to the voices of those who lived through the eras these walls depict. In doing so, you’ll witness not just a shift in art, but a society’s ongoing struggle and aspiration for peace.

Understanding the Political State: Definition, Functions, and Global Significance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Irish political murals are large-scale paintings or artworks displayed on walls, primarily in Northern Ireland, that depict political, religious, or cultural themes related to the region's history and conflicts.

The purpose of these murals is to express identity, commemorate historical events, honor figures, or make political statements, often reflecting the perspectives of unionist/loyalist or nationalist/republican communities.

They are most commonly found in working-class neighborhoods of Belfast and Derry/Londonderry, particularly in areas associated with unionist or nationalist communities.

Common themes include the Troubles, paramilitary groups, cultural symbols (e.g., the Union Jack or Irish tricolour), religious figures, and international solidarity with other struggles.

Yes, while many murals date back to the Troubles (1968–1998), new ones continue to be created, often reflecting contemporary issues, peace efforts, or evolving political and social narratives.