A political state refers to a structured entity that holds authority over a defined territory and population, characterized by its ability to make and enforce laws, maintain order, and provide public services. It is a fundamental concept in political science, representing the institutional framework through which governance is exercised. States are typically sovereign, meaning they possess the highest authority within their borders and are recognized as independent by other states in the international system. Key elements of a political state include a centralized government, a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, and the capacity to engage in diplomatic relations. Understanding the nature and functions of a political state is essential for analyzing power dynamics, policy-making, and the relationship between governments and their citizens.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sovereignty | Supreme authority within a territory, independent of external control. |

| Territory | Defined geographical area with recognized borders. |

| Population | Permanent residents or citizens living within the territory. |

| Government | Institutions and structures that exercise authority and make decisions. |

| Legitimacy | Recognition and acceptance of the government's authority by its citizens. |

| Monopoly of Force | Exclusive right to use force within its territory (e.g., police, military). |

| Legal System | Established laws and regulations to govern behavior and resolve disputes. |

| Recognition | Acknowledgment by other states as a legitimate political entity. |

| Permanence | Enduring existence beyond the lifespan of its leaders or governments. |

| Capacity to Enter Relations | Ability to engage in diplomatic and international relations. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Characteristics: Key traits defining a political state, including territory, population, sovereignty, and governance

- State Sovereignty: The authority of a state to govern itself without external interference or control

- Forms of Government: Different systems like democracy, monarchy, oligarchy, and authoritarian regimes within states

- State Functions: Roles such as lawmaking, security provision, economic regulation, and public services

- State Legitimacy: Sources of a state's authority, including consent, tradition, and legal frameworks

Definition and Characteristics: Key traits defining a political state, including territory, population, sovereignty, and governance

A political state is fundamentally defined by its territory, a geographically defined area over which it exercises authority. This territory is not merely land but includes airspace, bodies of water, and in some cases, exclusive economic zones. The clarity of borders is crucial, as it minimizes disputes and ensures the state’s ability to enforce laws and protect resources. For instance, the demarcation of the U.S.-Canada border has allowed both nations to manage trade, immigration, and security effectively, demonstrating how well-defined territory underpins stability.

Population is another critical trait, as a state must have a permanent populace to function. This population is not just a collection of individuals but a community bound by shared interests, rights, and obligations. The size and diversity of the population influence governance structures; larger, more heterogeneous populations often require decentralized systems to address varying needs. China’s population of over 1.4 billion necessitates a multi-tiered governance model, from central authority to local administrations, illustrating how population dynamics shape state organization.

Sovereignty is the cornerstone of a political state, granting it the ultimate authority to govern without external interference. This includes the power to make and enforce laws, manage foreign relations, and maintain order. Sovereignty is both internal, ensuring domestic legitimacy, and external, safeguarding against foreign encroachment. The European Union’s unique structure challenges traditional sovereignty by pooling certain powers among member states, yet each retains ultimate authority in critical areas, highlighting the evolving nature of sovereignty in a globalized world.

Governance, the mechanism through which a state exercises authority, varies widely but is essential for maintaining order and delivering public goods. Democratic, authoritarian, and hybrid systems each reflect different approaches to representation and decision-making. For example, Norway’s democratic governance emphasizes transparency and citizen participation, while Singapore’s technocratic model prioritizes efficiency and expertise. Effective governance hinges on legitimacy, accountability, and adaptability, ensuring the state remains responsive to its population’s needs.

Together, these traits—territory, population, sovereignty, and governance—form the bedrock of a political state. Each element is interdependent; a state’s territory defines its scope, its population provides purpose, sovereignty grants authority, and governance ensures functionality. Understanding these characteristics offers insight into how states operate, evolve, and interact in the global arena. Practical takeaways include the importance of clear borders, inclusive governance, and the balance between internal autonomy and external cooperation for a state’s long-term viability.

Am I a Political Moderate? Navigating the Spectrum of Beliefs

You may want to see also

State Sovereignty: The authority of a state to govern itself without external interference or control

State sovereignty is the cornerstone of international relations, a principle that asserts the exclusive right of a state to govern its own affairs without external interference. This concept, enshrined in the United Nations Charter, is both a shield and a sword for nations. It protects states from undue influence by external powers, allowing them to make decisions that align with their unique cultural, economic, and political contexts. However, it also places a heavy burden on states to act responsibly, as the international community often struggles to intervene in cases of internal atrocities, such as genocide or systemic human rights violations, without violating this principle.

Consider the case of Syria, where state sovereignty has been both a barrier to external intervention and a tool for the regime to suppress dissent. Despite widespread condemnation of the government’s actions, the principle of sovereignty has limited the ability of international actors to intervene directly. This example highlights the tension between respecting a state’s autonomy and addressing global moral imperatives. It raises a critical question: when, if ever, should the international community override sovereignty to prevent humanitarian crises?

To understand state sovereignty in practice, examine its three core components: territorial integrity, political independence, and legal equality. Territorial integrity ensures that no external entity can claim or control a state’s land without its consent. Political independence guarantees that a state’s government operates free from external dictation. Legal equality asserts that all states, regardless of size or power, are treated as equals under international law. These components are not merely theoretical; they are the foundation for treaties, diplomatic relations, and conflict resolution. For instance, the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia, often cited as the birth of modern sovereignty, ended the Thirty Years’ War by establishing these principles as the basis for European statecraft.

However, sovereignty is not absolute. States must balance their autonomy with international obligations, such as adhering to human rights norms and participating in global governance structures. The rise of transnational issues—climate change, terrorism, and pandemics—further complicates this balance. Take the COVID-19 pandemic, where states’ sovereign decisions on border closures and vaccine distribution had global repercussions. This underscores the need for a nuanced approach to sovereignty, one that acknowledges interdependence while preserving the core principle of self-governance.

In practical terms, states can strengthen their sovereignty by investing in robust institutions, fostering economic self-reliance, and engaging in strategic diplomacy. For developing nations, this might mean diversifying trade partners to reduce dependency on a single external power. For all states, it involves actively participating in international forums to shape norms and rules that reflect their interests. Ultimately, state sovereignty is not about isolation but about maintaining the autonomy to navigate an interconnected world on one’s own terms. It is a dynamic principle, evolving with global challenges, yet its core purpose remains unchanged: to empower states to govern themselves without external control.

School Boards and Politics: Unraveling the Complex Relationship

You may want to see also

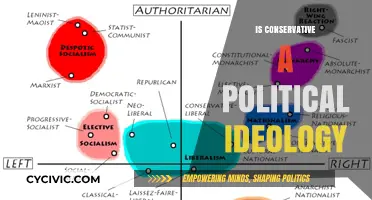

Forms of Government: Different systems like democracy, monarchy, oligarchy, and authoritarian regimes within states

A political state is fundamentally defined by its form of government, the structural framework through which power is exercised and decisions are made. Among the most prominent systems are democracy, monarchy, oligarchy, and authoritarian regimes, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations. Understanding these forms is essential for analyzing how states function, distribute authority, and address societal needs.

Democracy, often hailed as "rule by the people," operates on principles of representation, accountability, and majority rule. In this system, citizens participate directly or indirectly in governance, typically through elected officials. For instance, the United States employs a representative democracy, where voters elect leaders to make decisions on their behalf. However, democracies are not without challenges. They require an informed electorate, robust institutions, and safeguards against tyranny of the majority. Practical tips for strengthening democratic systems include promoting civic education, ensuring free and fair elections, and fostering independent media to hold leaders accountable.

In contrast, monarchies vest supreme authority in a single individual, often a king or queen, whose position is usually hereditary. While absolute monarchies, like Saudi Arabia, concentrate power in the monarch, constitutional monarchies, such as the United Kingdom, limit royal authority and integrate democratic elements. Monarchies can provide stability through continuity of leadership but risk stagnation if rulers are out of touch with societal needs. A key takeaway is that the effectiveness of a monarchy depends on the balance between tradition and adaptability.

Oligarchies are governed by a small, often wealthy or influential group, typically at the expense of the broader population. Historically, oligarchies have emerged in societies with stark economic inequalities, as seen in ancient Athens. Modern examples include corporate oligarchies, where economic elites wield disproportionate political power. This system often leads to exploitation and marginalization of the masses. To counter oligarchical tendencies, states must implement anti-corruption measures, enforce transparency, and ensure equitable access to resources.

Authoritarian regimes prioritize state control over individual freedoms, often under a single leader or party. Examples include North Korea and China, where dissent is suppressed, and media is tightly controlled. While authoritarian systems can achieve rapid decision-making and stability, they frequently result in human rights abuses and lack accountability. A comparative analysis reveals that authoritarian regimes may thrive in times of crisis but struggle to foster long-term innovation and societal well-being. For those living under such regimes, practical strategies include leveraging international alliances, documenting abuses, and advocating for incremental reforms.

In conclusion, the form of government a state adopts shapes its political landscape, societal dynamics, and global standing. Democracies emphasize participation and representation, monarchies balance tradition with governance, oligarchies reflect power imbalances, and authoritarian regimes prioritize control. Each system carries unique implications for citizens, requiring tailored approaches to address their strengths and weaknesses. By examining these forms, individuals can better navigate their political environments and advocate for systems that align with their values.

Mastering the Art of Polite Data Requests: A Professional Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

State Functions: Roles such as lawmaking, security provision, economic regulation, and public services

A political state is fundamentally defined by its ability to perform core functions that maintain order, ensure stability, and promote the welfare of its citizens. Among these, lawmaking stands as the bedrock of governance. Laws are not merely rules but frameworks that shape societal behavior, resolve disputes, and protect rights. For instance, the U.S. Congress enacts federal laws, while state legislatures tailor statutes to local needs. This dual system illustrates how lawmaking adapts to diverse populations while maintaining national cohesion. Effective lawmaking requires transparency, public input, and periodic review to remain relevant in a changing world.

Security provision is another critical state function, encompassing both internal and external protection. Internally, law enforcement agencies maintain public safety, while externally, military forces defend against foreign threats. Consider the role of NATO in collective defense, where member states pool resources to deter aggression. However, balancing security with civil liberties is a delicate task. Overreach in surveillance or policing can erode trust, as seen in debates over privacy laws. States must invest in training, oversight, and community engagement to ensure security measures are both effective and just.

Economic regulation is a less visible but equally vital function, shaping markets to prevent monopolies, ensure fair competition, and protect consumers. Central banks, like the Federal Reserve, manage monetary policy to stabilize economies, adjusting interest rates to control inflation or stimulate growth. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, governments worldwide implemented bailouts and regulations to prevent systemic collapse. Yet, overregulation can stifle innovation, while underregulation risks exploitation. Striking this balance requires data-driven policies and adaptability to global economic shifts.

Public services form the backbone of a state’s commitment to its citizens, providing essential resources like education, healthcare, and infrastructure. In Nordic countries, universal healthcare and free education are pillars of social welfare, funded by progressive taxation. These services not only improve quality of life but also foster social mobility and economic productivity. However, maintaining such systems demands efficient resource allocation and public accountability. Citizens must engage in oversight, ensuring funds are used effectively and services remain accessible to all, regardless of socioeconomic status.

In practice, these functions are interdependent, requiring coordination and prioritization. A state that excels in one area but neglects another risks instability. For instance, robust economic regulation without adequate public services can lead to inequality, while strong security without fair laws undermines legitimacy. Leaders must adopt a holistic approach, leveraging data, technology, and citizen feedback to optimize performance. Ultimately, the success of a state hinges on its ability to fulfill these roles with integrity, adaptability, and a focus on the common good.

Understanding Political Beliefs: A Guide to Identifying Your Ideology

You may want to see also

State Legitimacy: Sources of a state's authority, including consent, tradition, and legal frameworks

The authority of a state is not inherently given; it must be derived from sources that confer legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens and the international community. Among these sources, consent, tradition, and legal frameworks stand out as foundational pillars. Consent, often expressed through democratic processes like elections, grants a state its authority by reflecting the will of the governed. This principle is enshrined in the social contract theory, where individuals agree to surrender some freedoms in exchange for protection and order. For instance, the United States derives much of its legitimacy from its Constitution and regular elections, which allow citizens to choose their leaders and hold them accountable.

Tradition, on the other hand, provides legitimacy through continuity and cultural acceptance. Monarchies, such as those in the United Kingdom or Japan, rely heavily on historical lineage and ceremonial practices to justify their authority. This form of legitimacy is deeply rooted in collective memory and often transcends legal or rational arguments. In these cases, the state’s authority is not questioned because it is seen as a natural extension of cultural identity. However, tradition can be fragile; when societal values shift, as seen in modern debates about the relevance of monarchies, this source of legitimacy may weaken.

Legal frameworks serve as the backbone of state legitimacy by codifying rules and procedures that govern behavior and resolve disputes. Constitutions, laws, and judicial systems provide a structured environment where authority is exercised predictably and fairly. For example, Germany’s post-war reconstruction of legitimacy was built on the Basic Law, which established a federal system with checks and balances. This legal framework not only restored domestic trust but also reassured the international community of Germany’s commitment to democratic principles. Without such frameworks, state authority risks descending into arbitrariness, eroding its legitimacy.

A comparative analysis reveals that no single source of legitimacy is universally sufficient. Consent, tradition, and legal frameworks often intertwine to reinforce a state’s authority. In China, for instance, the Communist Party combines legal frameworks (through its constitution) with tradition (by invoking historical mandates like the "Chinese Dream") and a form of consent (via controlled elections and public opinion campaigns). This hybrid approach highlights the adaptability of legitimacy sources to different political contexts. However, it also underscores the risk of manipulation, as states may prioritize one source over others to consolidate power.

To ensure robust state legitimacy, leaders must balance these sources thoughtfully. Practical steps include fostering inclusive democratic processes to strengthen consent, preserving cultural institutions to uphold tradition, and maintaining transparent legal systems to ensure fairness. For example, countries transitioning from authoritarian rule, like South Africa post-apartheid, have successfully rebuilt legitimacy by combining truth and reconciliation commissions (tradition and consent) with a new constitutional framework (legal). Caution must be taken, however, to avoid over-reliance on any one source, as this can lead to fragility in the face of societal change or external pressure. Ultimately, legitimacy is a dynamic construct that requires continuous nurturing to sustain a state’s authority.

Navigating Neutrality: Practical Tips to Reduce Political Engagement

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political state is a structured political entity that possesses sovereignty, a defined territory, a government, and a population. It is recognized as a key actor in international relations and has the authority to make and enforce laws within its borders.

A political state refers to a legal and political entity with a government and recognized authority, while a nation is a group of people united by shared culture, language, history, or ethnicity. A nation can exist without a state (stateless nation), and a state can encompass multiple nations.

The essential elements of a political state are sovereignty (independence and authority), territory (defined geographical area), population (residents or citizens), and government (institutions to rule and enforce laws).

A political state can exist without formal recognition from other states, but recognition is crucial for its legitimacy and ability to participate in international affairs. Entities like Taiwan function as states but lack universal recognition.