Independent political expenditures refer to financial contributions made by individuals, corporations, unions, or other organizations to support or oppose political candidates or issues, without coordinating directly with the candidate’s campaign or political party. These expenditures are protected under the First Amendment and were significantly expanded by the 2010 Supreme Court decision in *Citizens United v. FEC*, which allowed unlimited spending by outside groups as long as it remains independent. Unlike direct campaign donations, which are subject to strict limits, independent expenditures can involve substantial amounts of money and are often used to fund advertisements, advocacy campaigns, or other efforts to influence elections. While they provide a platform for diverse voices in the political process, they have also raised concerns about transparency, accountability, and the potential for undue influence by wealthy donors or special interests.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Spending by individuals, groups, or organizations not coordinated with candidates, political parties, or campaigns. |

| Legal Basis (U.S.) | Protected under the First Amendment and regulated by the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) and Citizens United v. FEC (2010). |

| Types of Expenditures | Issue advocacy, express advocacy, and electioneering communications. |

| Reporting Requirements | Must be reported to the Federal Election Commission (FEC) if exceeding $250 in a calendar year. |

| Funding Sources | Can be funded by corporations, unions, nonprofits, and individuals. |

| Coordination Restrictions | Must be made independently without coordination with candidates or campaigns to maintain legality. |

| Transparency | Donors and expenditures are publicly disclosed, though "dark money" from nonprofits can obscure sources. |

| Impact on Elections | Can significantly influence elections through advertising, mobilization, and messaging. |

| Recent Trends | Increasing use of digital platforms and targeted ads in independent expenditures. |

| Criticisms | Concerns about undisclosed donors, potential for corruption, and unequal influence on elections. |

| Examples of Spenders | Super PACs, 501(c)(4) organizations, and wealthy individuals. |

Explore related products

$13.4 $23.95

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Legal Framework: Understanding independent expenditures under campaign finance laws and regulations

- Disclosure Requirements: Rules for reporting sources and amounts of independent political spending

- Coordination Rules: Prohibitions on collaboration between campaigns and independent expenditure groups

- Impact on Elections: How independent spending influences voter behavior and election outcomes

- Notable Cases and Controversies: Key legal battles and debates surrounding independent expenditures

Definition and Legal Framework: Understanding independent expenditures under campaign finance laws and regulations

Independent political expenditures are a critical yet often misunderstood component of campaign finance, operating outside the direct control of candidates, political parties, or their agents. Legally defined as spending by individuals, corporations, unions, or other groups that advocate for or against a candidate without coordinating with the candidate’s campaign, these expenditures are governed by a complex framework designed to balance free speech with transparency and fairness. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 *Citizens United v. FEC* decision, which lifted restrictions on corporate and union spending, significantly expanded the scope of independent expenditures, making them a dominant force in modern elections.

To qualify as an independent expenditure, the spending must meet specific criteria. First, it cannot be made in concert or cooperation with a candidate’s campaign. For example, a Super PAC can run ads supporting a candidate, but it cannot consult with the campaign about messaging, timing, or strategy. Second, the expenditure must explicitly advocate for or against a candidate using words like “vote for,” “elect,” “defeat,” or “reject.” Issue ads, which discuss a candidate’s stance without calling for a vote, do not qualify. These distinctions are crucial, as coordinated spending is subject to contribution limits and disclosure requirements, while independent expenditures are not.

The legal framework governing independent expenditures is rooted in the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) and subsequent court rulings. FECA requires groups making independent expenditures to disclose their donors and spending, but the *Citizens United* and *SpeechNow.org v. FEC* decisions created a loophole: organizations like Super PACs can accept unlimited contributions as long as they do not coordinate with candidates. This has led to a surge in outside spending, with billions of dollars flowing into elections from undisclosed or loosely regulated sources. Critics argue this undermines accountability, while proponents defend it as a First Amendment right.

Navigating this landscape requires vigilance. For organizations, ensuring compliance means maintaining strict firewalls between independent spenders and campaigns. For voters, understanding the source of political ads is essential to interpreting their credibility. Tools like the FEC’s online database allow the public to track independent expenditures, though the complexity of shell organizations and dark money groups often obscures the true origins of funding. As the legal framework continues to evolve, staying informed is key to participating in—or reforming—the system.

In practice, the impact of independent expenditures is profound. In the 2020 election cycle, outside groups spent over $1 billion on independent expenditures, dwarfing many candidates’ own campaign budgets. This raises questions about whose voices are amplified in the political process. While the legal framework aims to protect free speech, it also highlights the tension between individual rights and the public’s interest in fair, transparent elections. Whether viewed as a safeguard for democracy or a loophole for influence-peddling, independent expenditures are a defining feature of contemporary campaign finance.

Patronage Politics: How Favoritism Erodes Democracy and Public Trust

You may want to see also

Disclosure Requirements: Rules for reporting sources and amounts of independent political spending

Independent political expenditures, often made by outside groups not directly affiliated with candidates or parties, have become a significant force in modern elections. To ensure transparency and accountability, disclosure requirements mandate that these groups report the sources and amounts of their spending. These rules are designed to inform the public, deter corruption, and maintain the integrity of the electoral process. Without such transparency, voters would be left in the dark about who is influencing their elections and how.

Consider the practical steps involved in complying with these disclosure requirements. Organizations making independent expenditures must file detailed reports with regulatory bodies, such as the Federal Election Commission (FEC) in the United States. These reports typically include the names of donors, the amounts contributed, and how the funds were spent. For instance, a political action committee (PAC) supporting a candidate must disclose if it received $500,000 from a single donor and allocated $300,000 of that to television ads. Failure to report accurately can result in fines or legal penalties, underscoring the seriousness of these obligations.

A comparative analysis reveals that disclosure rules vary widely across jurisdictions. In the U.S., the Citizens United v. FEC decision loosened restrictions on corporate spending but maintained disclosure requirements. In contrast, countries like Canada impose stricter limits on both spending and disclosure, often requiring real-time reporting during election periods. These differences highlight the tension between free speech and the need for transparency, with each nation striking its own balance. For organizations operating internationally, navigating these disparate rules can be a complex but necessary task.

Persuasively, one could argue that robust disclosure requirements are essential for a healthy democracy. When voters know who is funding political ads, they can better evaluate the motives behind the messages. For example, an ad criticizing a candidate’s environmental record carries different weight if it’s funded by an oil industry group rather than a grassroots organization. Transparency empowers citizens to make informed decisions, reducing the influence of hidden agendas. Critics may claim these rules burden free speech, but the counterargument is clear: disclosure fosters trust in the electoral system.

Finally, a descriptive approach illustrates the real-world impact of these rules. Imagine a voter in a closely contested race who sees an ad attacking a candidate’s healthcare policy. Thanks to disclosure requirements, they can visit a public database and discover that the ad was funded by a pharmaceutical industry PAC. Armed with this knowledge, the voter can contextualize the ad’s claims and make a more informed judgment. This scenario demonstrates how disclosure requirements serve as a critical tool for voter education, bridging the gap between political spending and public awareness.

Mastering Political Maneuvering: Strategies for Influence and Success

You may want to see also

Coordination Rules: Prohibitions on collaboration between campaigns and independent expenditure groups

Independent political expenditures, by definition, must operate independently of candidate campaigns. This firewall is enforced through coordination rules—strict prohibitions designed to prevent collusion that could undermine the transparency and fairness of elections. These rules are the backbone of campaign finance law, ensuring that "independent" truly means independent.

Without these rules, the system would be ripe for abuse. Campaigns could funnel unlimited, undisclosed funds through seemingly independent groups, effectively circumventing contribution limits and donor disclosure requirements. The result? A distorted playing field where money, not voters, dictates outcomes.

Consider a hypothetical scenario: A candidate's campaign manager meets with the head of a Super PAC supporting their candidacy. They discuss polling data, messaging strategies, and even specific ad placements. This coordination, though seemingly innocuous, violates the spirit and letter of the law. The Super PAC, despite its "independent" status, has become an extension of the campaign, blurring the lines between regulated and unregulated spending.

Real-world examples abound. In 2018, the Federal Election Commission fined a political action committee for illegally coordinating with a congressional candidate's campaign through shared vendors and strategic planning. Such cases highlight the importance of vigilance in enforcing coordination rules.

So, what constitutes prohibited coordination? The rules are nuanced but generally encompass any "substantial discussion or negotiation" between a campaign and an independent expenditure group regarding campaign strategy, messaging, or spending decisions. This includes sharing internal polling data, discussing ad scripts, or even hinting at preferred attack angles against opponents.

Even indirect communication can trigger violations. For instance, a campaign consultant publicly stating a candidate's preferred messaging themes could be seen as a signal to independent groups, potentially crossing the coordination line.

Navigating these rules requires meticulous attention to detail. Campaigns and independent groups must establish strict information firewalls, avoiding any communication that could be construed as strategic coordination. This often involves separate legal counsel, distinct fundraising operations, and a clear separation of personnel. While challenging, adhering to these rules is crucial for maintaining the integrity of independent expenditures and, ultimately, the democratic process itself.

Understanding the Political Lame Duck: Definition, Impact, and Examples

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact on Elections: How independent spending influences voter behavior and election outcomes

Independent political expenditures, often funded by Super PACs, nonprofits, and wealthy individuals, inject vast sums into elections without coordinating directly with candidates. These expenditures, which can dwarf candidates’ own spending, reshape the electoral landscape by amplifying messages, targeting specific voter groups, and often introducing negative or polarizing content. Their influence on voter behavior and election outcomes is profound, yet their mechanisms are frequently misunderstood.

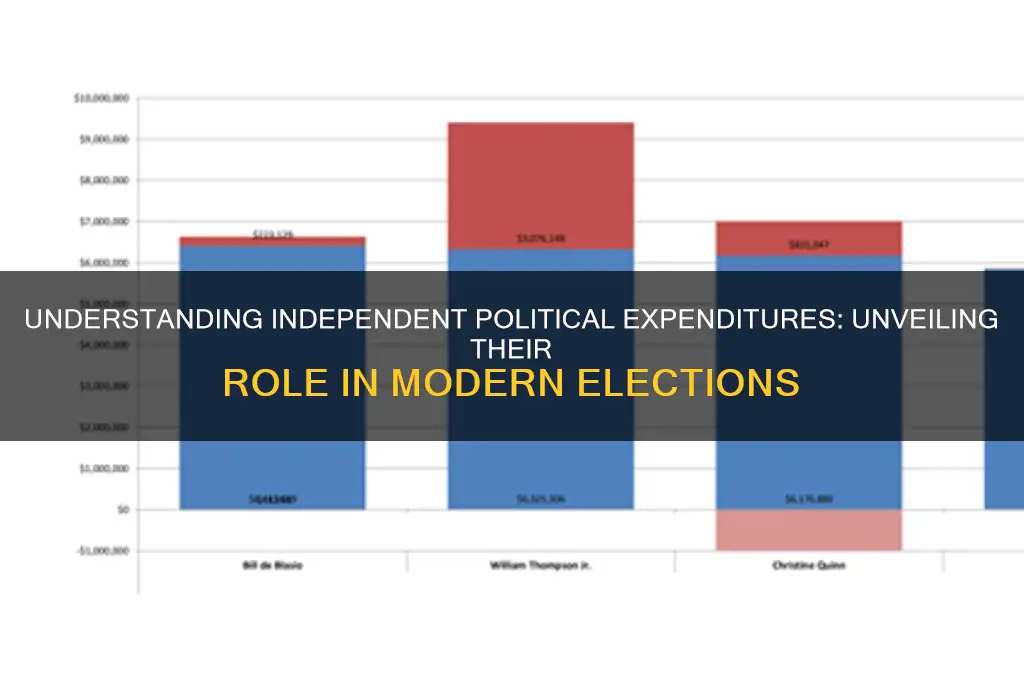

Consider the 2012 presidential election, where outside groups spent over $1 billion, much of it on attack ads. Research by the Wesleyan Media Project found that in battleground states, voters were exposed to an average of 30 political ads per day in the final weeks of the campaign. This bombardment of messaging, often funded by independent expenditures, can sway undecided voters or demobilize supporters of the targeted candidate. For instance, negative ads funded by Super PACs were linked to a 3-5% drop in candidate favorability among independent voters in key states. The takeaway? High-volume, independently funded ads can distort perceptions and shift electoral dynamics, particularly among less partisan voters.

To understand how this works, imagine a voter in a swing district who sees five ads daily criticizing a candidate’s record on the economy. Without counter-messaging from the candidate’s campaign, this narrative can take root, especially if the ads are emotionally charged or repetitive. Independent expenditures exploit this by bypassing campaigns’ strategic messaging, often focusing on divisive issues or personal attacks. A 2018 study in *The Journal of Politics* revealed that negative ads funded by outside groups were 20% more effective at reducing voter turnout than those from campaigns, particularly among younger voters (ages 18-29) and first-time voters.

However, the impact isn’t uniform. In local elections, where campaigns have fewer resources, independent spending can dominate the discourse entirely. For example, in a 2020 mayoral race in a mid-sized city, a single Super PAC spent $500,000 on digital ads targeting a candidate’s environmental policies. The candidate’s campaign, with a budget of $100,000, couldn’t compete, and the narrative shaped by the PAC became the defining issue for 40% of voters, according to post-election surveys. This illustrates how independent expenditures can disproportionately influence races with lower overall spending, effectively hijacking the conversation.

Practical tips for voters and campaigns? First, voters should verify claims in ads through nonpartisan fact-checking organizations like PolitiFact or FactCheck.org. Campaigns, especially in resource-constrained races, should focus on grassroots engagement and earned media to counterbalance the influence of outside spending. Policymakers could also consider reforms like real-time disclosure requirements for independent expenditures, which would allow campaigns and voters to respond more effectively. Without such measures, independent spending will continue to distort elections, privileging those with deep pockets over the voices of ordinary voters.

Were Political Machines Exclusively Democratic? Unraveling Historical Party Affiliations

You may want to see also

Notable Cases and Controversies: Key legal battles and debates surrounding independent expenditures

The landmark 2010 *Citizens United v. FEC* Supreme Court decision remains the most pivotal legal battle surrounding independent expenditures. By ruling that corporations and unions could spend unlimited amounts on political speech, the Court effectively unleashed a torrent of outside spending in elections. This decision hinged on the interpretation of the First Amendment, with the majority arguing that restricting such expenditures violated free speech rights. Critics, however, contend that it opened the floodgates for wealthy interests to unduly influence elections, blurring the line between independent and coordinated spending.

A contrasting case, *McCutcheon v. FEC* (2014), further expanded the scope of independent expenditures by striking down aggregate contribution limits. While not directly about independent spending, it reinforced the legal framework favoring deregulation of political money. This decision highlighted the ongoing tension between protecting individual speech and preventing corruption or the appearance thereof. Together, these cases illustrate how legal interpretations of independent expenditures have reshaped the campaign finance landscape.

One of the most contentious debates revolves around the definition of "coordination" between independent spenders and candidates. In *FEC v. Cruz* (2022), the Supreme Court invalidated a provision limiting candidates from repaying personal loans to their campaigns, further complicating efforts to distinguish between independent and coordinated activity. This ruling underscored the difficulty of regulating expenditures without infringing on constitutional rights, leaving regulators and reformers in a perpetual state of legal whack-a-mole.

Practical implications of these controversies are evident in the rise of Super PACs, which exploit the legal distinction between independent and coordinated spending. For instance, the 2012 election saw Restore Our Future, a Super PAC supporting Mitt Romney, raise over $150 million in independent expenditures. While legally compliant, such activity raises ethical questions about transparency and accountability. To navigate this terrain, voters and advocates must scrutinize disclosure reports and demand clearer definitions of coordination.

In conclusion, the legal battles over independent expenditures reflect broader ideological clashes about the role of money in politics. From *Citizens United* to *FEC v. Cruz*, each case has redefined the boundaries of permissible spending, often at the expense of public trust. As the debate continues, stakeholders must balance constitutional protections with the need for equitable electoral participation, ensuring that independent expenditures do not become a tool for dominance by the few.

Is All Terrorism Political? Unraveling the Complex Motivations Behind Extremism

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Independent political expenditures are funds spent by individuals, corporations, unions, or other organizations to support or oppose political candidates or issues, without coordinating directly with the candidate’s campaign or political party.

Anyone, including individuals, corporations, unions, and nonprofit organizations, can make independent political expenditures as long as they do not coordinate with candidates, campaigns, or political parties.

No, independent political expenditures are different from campaign contributions. Contributions are donations made directly to a candidate or political party, while independent expenditures are made independently and cannot be coordinated with the campaign.

No, there are no limits on the amount that can be spent on independent political expenditures, as established by the Supreme Court’s *Citizens United v. FEC* decision in 2010. However, disclosure requirements may apply depending on the jurisdiction.