House seats, in the context of U.S. politics, refer to the 435 voting seats in the House of Representatives, the lower chamber of Congress. These seats are apportioned among the 50 states based on population, with each state guaranteed at least one representative. Members of the House, known as Representatives, serve two-year terms and are directly elected by voters in their respective congressional districts. House seats are highly contested in elections, as they play a crucial role in shaping legislation, overseeing government operations, and reflecting the political balance of power between the Democratic and Republican parties. The composition of House seats can shift dramatically based on national and local political trends, making them a key indicator of public sentiment and a focal point in American political discourse.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | House seats refer to the positions held by members in the U.S. House of Representatives, the lower chamber of Congress. |

| Total Number of Seats | 435 (fixed by law since 1913, apportioned among states based on population). |

| Apportionment | Seats are reapportioned every 10 years following the U.S. Census to reflect population changes. |

| Term Length | 2 years (members must run for reelection every two years). |

| Eligibility Requirements | Must be at least 25 years old, a U.S. citizen for 7 years, and a resident of the state they represent. |

| Role | Legislate, oversee federal budgets, and serve as a check on the executive and judicial branches. |

| Leadership | Speaker of the House (elected by members) leads the chamber and sets the legislative agenda. |

| Political Significance | Reflects the balance of power between political parties (e.g., Democrats vs. Republicans). |

| Redistricting | State legislatures redraw district boundaries every 10 years, often leading to gerrymandering. |

| Vacancies | Filled through special elections called by state governors. |

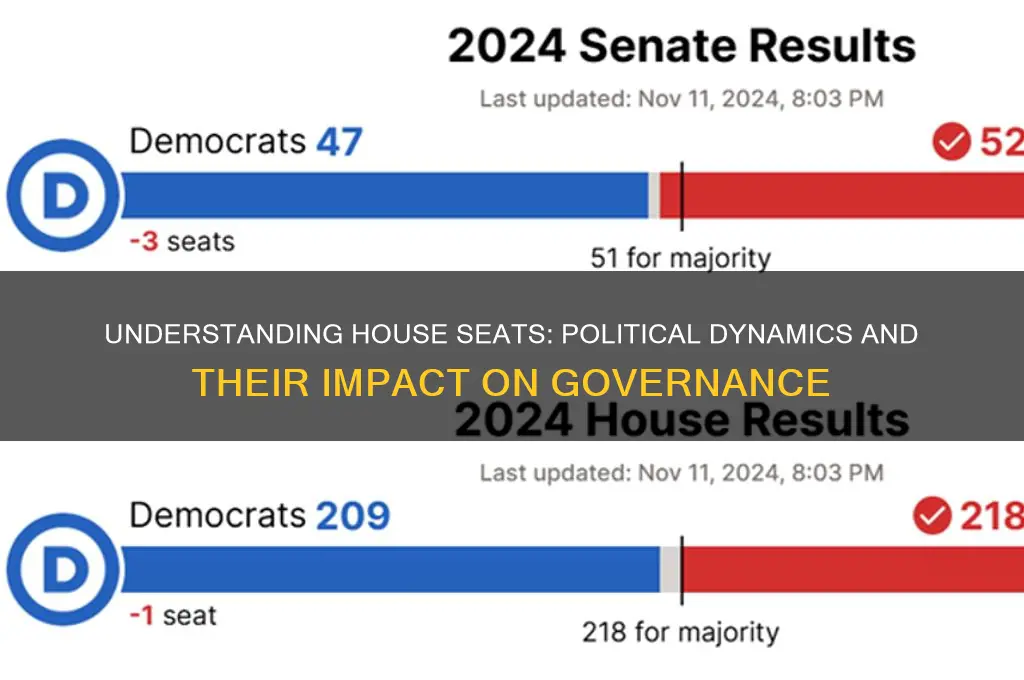

| Current Party Breakdown | As of October 2023: 213 Democrats, 222 Republicans (subject to change due to elections or vacancies). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Apportionment Process: How seats are distributed among states based on population census data

- Gerrymandering Impact: Manipulating district boundaries to favor specific political parties or groups

- Swing Districts: Areas where voters shift between parties, influencing election outcomes

- Incumbent Advantage: Benefits held by current officeholders in reelection campaigns

- Term Limits: Rules restricting how long representatives can serve in the House

Apportionment Process: How seats are distributed among states based on population census data

The U.S. House of Representatives is a dynamic institution, with its 435 seats constantly shifting among states to reflect population changes. This apportionment process, rooted in the Constitution and refined over centuries, ensures that representation in the House mirrors the nation’s demographic evolution. Every ten years, following the census, the process recalibrates the distribution of seats, balancing power between states based on their resident populations.

At its core, the apportionment process is a mathematical exercise. The method of equal proportions, adopted in 1941, is the current standard. It assigns seats by comparing each state’s population to a "priority value," calculated by dividing the population by the geometric mean of successive seat numbers. For example, if State A has 10 million residents, its priority value for the first seat is 10 million, for the second seat it’s 10 million divided by √(1×2), and so on. Seats are allocated to states with the highest priority values until all 435 seats are distributed. This method minimizes the disparity in representation per capita among states.

However, the process is not without challenges. Small states are guaranteed at least one seat, regardless of population, which can skew representation in their favor. For instance, Wyoming’s single representative serves approximately 580,000 residents, while California’s representatives each serve over 760,000. This imbalance highlights the tension between ensuring every state has a voice and maintaining proportional representation. Additionally, the census itself can introduce inaccuracies, such as undercounting marginalized communities, which further complicates equitable apportionment.

To navigate these complexities, transparency and public engagement are essential. The Census Bureau and Congress must work together to ensure data accuracy and fairness in the apportionment formula. Citizens can play a role by participating in the census and advocating for reforms that address systemic biases. Understanding the apportionment process empowers individuals to hold leaders accountable and ensures that the House of Representatives truly reflects the nation’s diversity.

In conclusion, the apportionment process is a critical mechanism for maintaining democratic balance in the U.S. House. While its mathematical precision and historical evolution are commendable, ongoing vigilance is required to address inherent challenges. By staying informed and engaged, Americans can help ensure that this process remains a cornerstone of fair and equitable representation.

Campus Tours and Politics: Uncovering Hidden Agendas in College Visits

You may want to see also

Gerrymandering Impact: Manipulating district boundaries to favor specific political parties or groups

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party or group, has become a cornerstone of political strategy in many democracies. By manipulating these boundaries, parties can consolidate their voter base or dilute the influence of opposing voters, effectively skewing election outcomes. For instance, in the 2012 U.S. House elections, Republicans won 49% of the popular vote but secured 54% of House seats, a disparity largely attributed to gerrymandering. This tactic not only distorts representation but also undermines the principle of "one person, one vote," creating a system where some votes carry more weight than others.

To understand gerrymandering’s impact, consider its two primary forms: cracking and packing. Cracking involves spreading opposition voters across multiple districts to ensure they never form a majority, while packing concentrates them into a single district to limit their influence elsewhere. For example, in North Carolina’s 2016 redistricting, Republicans packed Democratic voters into three districts, securing 10 out of 13 House seats despite winning only 53% of the statewide vote. Such strategies highlight how gerrymandering can silence minority voices and entrench political power, even when public opinion shifts.

The consequences of gerrymandering extend beyond election results. It fosters political polarization by creating "safe" districts where incumbents face little competition, reducing incentives for moderation or bipartisan cooperation. This dynamic was evident in the 2020 U.S. House races, where 89% of incumbents ran in districts considered non-competitive, according to the Cook Political Report. Moreover, gerrymandering discourages voter turnout in packed districts, as residents perceive their votes as futile. In Wisconsin, for instance, Democratic voters in heavily gerrymandered districts reported feeling disenfranchised, contributing to lower participation rates compared to swing districts.

Combatting gerrymandering requires systemic reforms. Independent redistricting commissions, as used in California and Arizona, can remove partisan bias from the process. These commissions, composed of non-partisan citizens, draw maps based on criteria like population equality and compactness, not political advantage. Additionally, courts have increasingly intervened, with the Supreme Court ruling in *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019) that federal courts cannot address partisan gerrymandering, leaving states to enact their own solutions. Practical steps for activists include advocating for transparency in redistricting, leveraging technology to analyze proposed maps, and supporting legislation like the For the People Act, which promotes fairer districting practices.

Ultimately, gerrymandering’s impact is a stark reminder of how procedural manipulations can distort democratic ideals. While it may offer short-term gains for parties, it erodes public trust and weakens governance. Addressing this issue demands vigilance, innovation, and a commitment to equitable representation. As voters and advocates, understanding these mechanisms is the first step toward reclaiming a political system that truly reflects the will of the people.

From Green to Gridlock: How Environmental Issues Became Political Battles

You may want to see also

Swing Districts: Areas where voters shift between parties, influencing election outcomes

In the intricate dance of American politics, swing districts emerge as the pivotal battlegrounds where elections are won or lost. These are the areas where voters don’t reliably lean Democratic or Republican, instead shifting allegiances based on candidates, issues, or national moods. For instance, in 2020, Arizona’s 6th Congressional District flipped from Republican to Democratic, reflecting broader trends in suburban areas where moderate voters prioritized healthcare and economic stability over party loyalty. Such districts are the political equivalent of a weather vane, signaling shifts in public sentiment long before they become national trends.

To understand swing districts, consider them as microcosms of the broader electorate’s complexities. Unlike safe seats, where incumbents can coast to victory, swing districts demand candidates tailor their messages to appeal to a diverse, often polarized, voter base. Take Pennsylvania’s 8th District, which has swung between parties in recent cycles. Here, candidates must balance urban progressives’ demands for social justice with rural conservatives’ focus on gun rights and agriculture. This delicate balancing act requires data-driven strategies, such as targeting independent voters aged 30–50, who often decide close races. Campaigns in these districts invest heavily in ground operations, with door-to-door canvassing and localized digital ads proving more effective than blanket national messaging.

The influence of swing districts extends beyond individual races, shaping national policy agendas. Since these districts often determine control of the House, parties prioritize issues that resonate there. For example, during the 2018 midterms, Democratic victories in swing districts like Virginia’s 7th were fueled by opposition to GOP healthcare policies. Conversely, in 2022, inflation and crime became dominant themes as Republicans targeted suburban swing districts in states like New York and California. This dynamic forces parties to moderate their platforms, as extreme positions risk alienating the very voters who decide elections. As a result, swing districts act as a check on ideological purity, pushing both parties toward the center.

For voters and activists, identifying and engaging with swing districts offers a strategic advantage. Tools like the Cook Political Report’s Partisan Voting Index (PVI) can help pinpoint these areas, though local factors often defy national trends. For instance, while Michigan’s 8th District has a PVI leaning Republican, its working-class electorate has recently favored Democrats on economic issues. Practical tips for engagement include volunteering in get-out-the-vote efforts, donating to competitive races, and amplifying local issues on social media. By focusing on these districts, individuals can maximize their impact, as a small shift in voter turnout or persuasion can tip the balance in favor of one party.

Ultimately, swing districts are the pulse of American democracy, reflecting its dynamism and divisions. They remind us that elections are not won in deep-blue or deep-red strongholds but in the gray areas where voters weigh competing priorities. As the nation grows more polarized, these districts will only increase in importance, serving as both a challenge and an opportunity for candidates and citizens alike. Understanding them is not just a political exercise—it’s a roadmap to influencing the future of the country.

Understanding Political Law: Key Principles and Real-World Applications

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Incumbent Advantage: Benefits held by current officeholders in reelection campaigns

In the high-stakes arena of House elections, incumbents enjoy a formidable edge that often tilts the scales in their favor. Statistical evidence underscores this phenomenon: historically, over 90% of incumbent representatives seeking reelection secure their seats. This staggering success rate isn’t merely coincidental; it’s a testament to the systemic advantages embedded in their role. From name recognition to access to resources, incumbents leverage their position to build a nearly insurmountable lead over challengers. Understanding these advantages is crucial for anyone analyzing political races or strategizing campaigns.

One of the most tangible benefits incumbents possess is their ability to fundraise effectively. Campaign finance data reveals that incumbents consistently outraise their opponents, often by a margin of 3:1 or more. This financial dominance isn’t just about personal wealth; it stems from their established networks of donors, including special interest groups and party backers. For instance, a sitting representative can tap into PAC contributions or host exclusive events, while challengers struggle to gain traction. This financial head start translates into more ads, better staff, and a polished campaign machine—all critical in swaying undecided voters.

Beyond money, incumbents wield the power of visibility and legislative influence. Holding office grants them a platform to shape policy and deliver tangible benefits to their districts, such as securing federal grants or sponsoring popular bills. These actions are then amplified through taxpayer-funded mailings, known as franking privileges, which allow incumbents to communicate directly with constituents without campaign costs. Challengers, lacking such tools, must rely on earned media or costly advertising to build name recognition. This disparity in visibility often leaves incumbents as the default choice for voters who prioritize familiarity over fresh ideas.

However, the incumbent advantage isn’t just structural—it’s psychological. Voters tend to favor the status quo, a bias known as the “sunk cost fallacy” in political science. Incumbents capitalize on this by framing elections as a referendum on their performance rather than a choice between candidates. Even in polarized climates, this strategy works: a 2020 study found that incumbents who highlighted their bipartisan efforts saw a 5% bump in approval ratings. Challengers, on the other hand, must work twice as hard to convince voters that change is worth the risk.

To counterbalance this advantage, challengers must adopt targeted strategies. First, focus on local issues where the incumbent’s record is weak—for example, unfulfilled promises or controversial votes. Second, harness grassroots energy through digital campaigns and community organizing to bypass traditional funding gaps. Finally, leverage endorsements from trusted figures or organizations to build credibility. While the incumbent advantage is significant, it’s not insurmountable; history shows that well-executed campaigns can flip seats, even against the odds.

Understanding Political Redistricting: Process, Impact, and Controversies Explained

You may want to see also

Term Limits: Rules restricting how long representatives can serve in the House

Term limits for House representatives have been a subject of debate, with proponents arguing they prevent entrenched incumbency and encourage fresh perspectives. Currently, members of the U.S. House of Representatives face no federal restrictions on the number of terms they can serve, allowing them to remain in office indefinitely if reelected. This contrasts with the presidency, which has a two-term limit established by the 22nd Amendment. Advocates for House term limits suggest a cap of 6 to 12 years (3 to 6 terms) could reduce careerism and increase accountability, as representatives would be less focused on reelection and more on constituent needs.

Implementing term limits for the House would require a constitutional amendment, a complex process demanding two-thirds approval in both chambers of Congress or a constitutional convention called by two-thirds of state legislatures, followed by ratification by three-fourths of the states. Historically, efforts to impose term limits via state laws in the 1990s were struck down by the Supreme Court in *U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton* (1995), which ruled that states cannot impose additional qualifications beyond those outlined in the Constitution for federal office. This decision underscores the necessity of a federal solution, such as an amendment, to enact term limits for House members.

Critics of term limits argue they could diminish institutional knowledge and legislative expertise, as seasoned representatives would be replaced by newcomers with steeper learning curves. For instance, complex issues like healthcare reform or foreign policy might suffer from frequent turnover, as new members would lack the experience to navigate intricate legislative processes. Additionally, term limits could shift power toward unelected staffers, lobbyists, and bureaucrats, who would become the de facto institutional memory, potentially undermining democratic accountability.

A comparative analysis reveals mixed outcomes in states with legislative term limits. In California, for example, term limits for state legislators have led to a faster rotation of lawmakers but have also been criticized for reducing continuity and increasing reliance on lobbyists. Conversely, in states like New York, where no term limits exist, long-serving representatives often develop deep expertise but may also become disconnected from their constituents. Balancing these trade-offs requires careful consideration of the specific needs and dynamics of the House of Representatives.

Practically, if term limits were introduced, a phased implementation could mitigate disruptions. For instance, a grandfather clause could exempt current representatives, while new members would be subject to the limits. Pairing term limits with robust training programs for incoming representatives could also address concerns about lost expertise. Ultimately, the decision to impose term limits hinges on whether the benefits of refreshing leadership outweigh the risks of institutional instability, a question that continues to divide policymakers and the public alike.

Exploring Global Relations: Understanding International Politics Class Essentials

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

House seats refer to the positions held by elected representatives in the lower chamber of a legislative body, such as the House of Representatives in the United States Congress.

House seats are determined through elections, where voters in specific districts or constituencies choose their representatives based on political campaigns and party affiliations.

House seats play a crucial role in creating and passing laws, overseeing government budgets, and representing the interests of their constituents at the national level.

In many systems, such as the U.S., house seats are up for election every two years, ensuring regular accountability to the electorate.

Yes, house seats can change party control based on election outcomes, which can shift the balance of power and influence legislative priorities.