French political pamphlets, a significant form of political expression in France, have played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and influencing political discourse throughout history. These concise, often polemical writings emerged as a powerful tool during periods of social and political upheaval, such as the French Revolution and the Enlightenment, allowing authors to critique authority, advocate for reform, and mobilize public sentiment. Typically distributed widely and anonymously to evade censorship, pamphlets addressed a range of issues, from monarchy and religion to democracy and human rights, reflecting the diverse ideologies of their time. Their accessibility and directness made them an effective medium for both intellectuals and the general populace, cementing their legacy as a vital component of French political and cultural heritage.

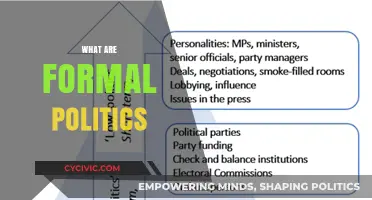

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Short, unbound booklets or writings advocating political ideas or critiques. |

| Historical Origin | Emerged during the French Wars of Religion (16th century) and popularized during the Enlightenment and French Revolution. |

| Purpose | To influence public opinion, mobilize support, or critique political figures/policies. |

| Format | Typically 8-48 pages, unbound, and cheaply produced for mass distribution. |

| Content | Satirical, polemical, or persuasive, often using rhetoric, anecdotes, and facts. |

| Anonymity | Frequently published anonymously or under pseudonyms to avoid censorship or persecution. |

| Distribution | Sold cheaply in public spaces, distributed in salons, or circulated clandestinely. |

| Impact | Played a pivotal role in shaping public discourse during the French Revolution and other political movements. |

| Notable Examples | Qu'est-ce que le Tiers État? (What is the Third Estate?) by Abbé Sieyès (1789). |

| Legal Status | Often subject to censorship; authors risked imprisonment or exile under repressive regimes. |

| Modern Relevance | Similar to modern blogs, opinion pieces, or social media posts in their role in political discourse. |

| Language | Written in accessible French to reach a broad audience, including the literate public. |

| Tone | Passionate, urgent, and often radical, reflecting the political climate of the time. |

| Historical Context | Flourished during periods of political upheaval, such as the Enlightenment and Revolution. |

| Cultural Significance | Symbolize the power of free speech and the role of literature in political change. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

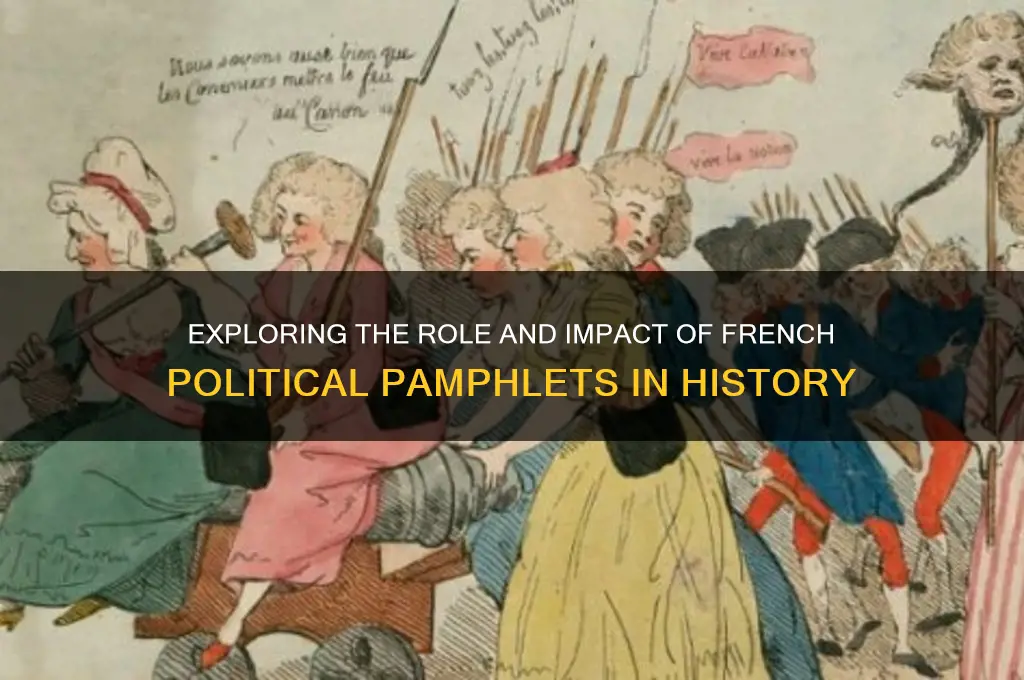

Historical origins of French political pamphlets

French political pamphlets, often sharp and succinct, trace their roots to the early modern period, emerging as a potent tool during the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598). These conflicts, pitting Catholics against Huguenots, saw the proliferation of printed texts designed to sway public opinion. Pamphlets like *La Défense de l’Église* (1563) exemplified this trend, blending theological argument with political rhetoric to mobilize factions. Their brevity and accessibility made them ideal for a literate but time-constrained audience, marking the beginning of their role as instruments of ideological warfare.

The 18th century, particularly the Enlightenment, saw pamphlets evolve into vehicles for radical thought. Voltaire, Rousseau, and others used them to critique the monarchy, clergy, and social inequalities. *Lettres philosophiques* (1734) and *Le Contrat Social* (1762) circulated widely, though often clandestinely, due to censorship. This era cemented the pamphlet’s status as a medium for subversion, blending philosophical argument with calls for reform. Their production surged in the lead-up to the French Revolution, reflecting and shaping the zeitgeist of dissent.

The Revolution itself transformed pamphlets into weapons of mass mobilization. From *Qu’est-ce que le Tiers État?* (1789) by Sieyès to Marat’s *L’Ami du peuple*, these texts galvanized public sentiment, often with incendiary language. Their role was dual: to inform and to incite. Printed in large quantities and distributed in cafés, markets, and salons, they reached a diverse audience, including the semi-literate, who had them read aloud. This period demonstrated the pamphlet’s power to bridge the gap between elite discourse and popular action.

Post-Revolution, pamphlets continued to thrive, adapting to new political landscapes. During the 19th century, they became tools for both reactionaries and revolutionaries, from royalist tracts opposing Napoleon to socialist manifestos like *Le Manifeste du Parti Communiste* (1848). Their format remained consistent: concise, provocative, and often anonymous, allowing authors to evade persecution. This adaptability ensured their relevance across regimes, from the Bourbon Restoration to the Third Republic, proving their enduring utility in French political culture.

Understanding the historical origins of French political pamphlets reveals their role as barometers of societal tension and catalysts for change. From religious strife to revolutionary fervor, they have mirrored and molded public opinion. For modern readers, studying these texts offers insights into the evolution of political communication. Practical tip: explore digitized archives like Gallica to trace their development, noting shifts in tone, audience, and purpose across centuries. This historical lens enriches our grasp of how ideas spread and societies transform.

Understanding Political Globalization: Key Examples and Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Key figures and authors in pamphlet writing

French political pamphlets have long been a powerful medium for dissent, satire, and reform, often flourishing during periods of social upheaval. Among the key figures and authors who shaped this genre, Voltaire stands out as a master of wit and critique. His pamphlets, such as *Philosophical Letters* and *Treatise on Tolerance*, employed sharp irony to expose religious hypocrisy and political corruption. Voltaire’s ability to blend intellectual rigor with accessible language made his works widely influential, inspiring both the Enlightenment and later revolutionary thought. His legacy lies in demonstrating how pamphlets could serve as both a weapon and a tool for enlightenment.

Another pivotal figure is Jean-Paul Marat, whose radical voice defined the French Revolution’s most tumultuous phase. Through his pamphlet *L’Ami du peuple* (The Friend of the People), Marat championed the rights of the sans-culottes and relentlessly attacked the monarchy and moderates. His writing was incendiary, often calling for direct action against perceived enemies of the revolution. Marat’s style was unapologetically confrontational, reflecting the urgency of the times. His assassination in 1793 only cemented his status as a martyr for the cause, but his pamphlets remain a testament to the power of unyielding advocacy in political literature.

Contrastingly, Olympe de Gouges used pamphlets to advance a different kind of revolution—one centered on gender equality. Her 1791 work, *Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen*, directly challenged the male-dominated political discourse of the era. De Gouges’ writing was both bold and methodical, mirroring the structure of the Declaration of the Rights of Man to highlight the exclusion of women. Her pamphlets were not just calls for reform but blueprints for a more inclusive society. Despite facing ridicule and eventual execution, her contributions laid the groundwork for feminist thought in France and beyond.

Finally, the collective efforts of anonymous pamphleteers during the Revolution cannot be overlooked. These writers, often operating under pseudonyms or in secret presses, produced a deluge of material that fueled public opinion. Their works ranged from satirical cartoons to detailed policy critiques, democratizing political discourse in unprecedented ways. While individual authors like Voltaire or Marat left indelible marks, the anonymous pamphleteers exemplified the genre’s grassroots nature. Their anonymity protected them from persecution but also underscored the idea that political critique was a duty shared by all citizens.

In studying these figures, one takeaway is clear: pamphlet writing in France was not merely a literary exercise but a catalyst for change. Each author brought a unique style and purpose, from Voltaire’s intellectual provocations to Marat’s revolutionary fervor, de Gouges’ feminist vision, and the collective voice of the anonymous. Together, they illustrate how pamphlets could dismantle old orders, shape new ideologies, and mobilize masses. For modern readers, their works offer both historical insight and a reminder of the enduring power of written dissent.

Trump's Legacy: The End of Political Comedy as We Knew It

You may want to see also

Role in the French Revolution

French political pamphlets, often biting and unapologetically partisan, served as the social media of the 18th century, amplifying grievances and shaping public opinion during the French Revolution. These short, cheaply produced booklets were the ideal medium for a populace hungry for information and eager to participate in the political upheaval. Their role in the Revolution was multifaceted, acting as both a catalyst for change and a tool for manipulation.

Imagine a time before Twitter threads or viral Facebook posts. News traveled slowly, and information was controlled by the elite. Pamphlets, with their accessibility and affordability, democratized political discourse. They were sold on street corners, read aloud in cafes, and passed hand-to-hand, reaching a wide audience across social strata. This widespread dissemination of ideas fueled the revolutionary fervor, allowing radical notions of liberty, equality, and fraternity to permeate even the most remote villages.

One of the most potent weapons in the pamphleteer's arsenal was satire. Caricatures and biting wit exposed the excesses of the monarchy and the clergy, making complex political issues understandable and emotionally resonant. Pamphlets like "What is the Third Estate?" by Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès, a seemingly innocuous question, became a rallying cry for the disenfranchised masses, highlighting the vast inequality between the privileged orders and the common people. This pamphlet, widely circulated, played a crucial role in galvanizing support for the Estates-General and ultimately, the storming of the Bastille.

However, the power of pamphlets was a double-edged sword. Their anonymity and lack of accountability allowed for the spread of misinformation, rumors, and vicious attacks. Counter-revolutionary pamphlets, often funded by the aristocracy, sought to discredit the Revolution and sow fear among the populace. The sheer volume of conflicting information created a climate of confusion and distrust, making it difficult for individuals to discern truth from propaganda.

Despite these drawbacks, the impact of pamphlets on the French Revolution cannot be overstated. They provided a platform for diverse voices, challenged established power structures, and mobilized public opinion on an unprecedented scale. They were a vital tool for both revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries, shaping the course of history through the power of the written word. Understanding their role offers valuable insights into the complexities of revolutionary movements and the enduring power of communication in shaping societal change.

Was Jared Loughner Politically Motivated? Unraveling the Tucson Shooting Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Modern usage and digital evolution

French political pamphlets, historically tools of dissent and enlightenment, have undergone a metamorphosis in the digital age. Once confined to clandestine printing presses and underground networks, these texts now thrive in the boundless expanse of the internet. Platforms like Twitter, Medium, and independent blogs have become the new bastions of political pamphleteering, allowing for instantaneous dissemination and global reach. The essence remains—provocation, critique, and mobilization—but the medium has evolved to exploit the interactive and viral nature of digital communication.

Consider the *gilets jaunes* movement, where digital pamphlets circulated rapidly, galvanizing protests against economic inequality. These modern pamphlets often take the form of viral threads, infographics, or video essays, blending brevity with impact. Unlike their printed predecessors, they are not static; they evolve through comments, shares, and edits, creating a dynamic dialogue between author and audience. This interactivity amplifies their influence, turning readers into participants in the political discourse.

To craft an effective digital pamphlet, focus on clarity and concision. Start with a provocative headline—think *"Macron’s Policies: A Recipe for Division?"*—and structure your argument in digestible chunks. Use visuals sparingly but strategically; a well-designed chart can convey more than a paragraph of text. Leverage hashtags to increase visibility, but avoid oversaturation. For instance, #RépubliqueEnMarche or #JusticeSociale can anchor your content within relevant conversations. Finally, end with a call to action—whether it’s signing a petition, attending a rally, or sharing the post—to transform engagement into mobilization.

A cautionary note: the digital realm’s speed and anonymity can dilute the rigor of traditional pamphleteering. Fact-checking and sourcing remain essential, even in the heat of online activism. A single inaccuracy can undermine credibility and derail the message. Additionally, the algorithmic nature of social media often prioritizes sensationalism over substance. Resist the temptation to sacrifice depth for virality; a well-reasoned argument, even if it spreads slowly, carries more enduring power than a fleeting trend.

In conclusion, the modern French political pamphlet is a hybrid of tradition and innovation. It retains the urgency and audacity of its historical roots while harnessing the tools of the digital age to reach and engage wider audiences. By balancing brevity with depth, interactivity with integrity, and virality with substance, today’s pamphleteers can wield this evolved medium to challenge, inspire, and transform.

Understanding Acrimony: The Bitter Divide in Modern Political Discourse

You may want to see also

Impact on French political discourse

French political pamphlets, often sharp and succinct, have historically served as catalysts for public debate, shaping discourse by distilling complex issues into accessible, provocative arguments. Consider *J’accuse…!* by Émile Zola, a seminal pamphlet that galvanized public opinion during the Dreyfus Affair. Its direct, emotive language not only exposed injustice but also redefined the role of intellectuals in political activism. Such pamphlets act as rhetorical grenades, fragmenting complacency and forcing citizens to confront uncomfortable truths. Their brevity ensures wide dissemination, while their polemical tone fosters polarization—a double-edged sword that both energizes and divides the polity.

To understand their impact, examine their structural design: pamphlets are crafted for maximum persuasion, blending facts with hyperbole to sway hearts and minds. For instance, Voltaire’s *Treatise on Tolerance* employed historical examples and moral appeals to critique religious fanaticism, influencing Enlightenment thought. Modern French pamphlets, like those during the *gilets jaunes* protests, mimic this strategy, using social media to amplify reach. However, their effectiveness hinges on timing and context. A pamphlet released during a political lull may fizzle, while one coinciding with public unrest can ignite revolutions. Practitioners should note: timing is as critical as content.

Contrast French pamphlets with other political mediums, such as speeches or manifestos, to grasp their unique influence. Unlike speeches, which are ephemeral and audience-specific, pamphlets endure as tangible artifacts, often reprinted and referenced. Unlike manifestos, which outline comprehensive ideologies, pamphlets focus on singular issues, making them more actionable. For example, the *Cahiers de Doléances* of 1789, while not pamphlets in the traditional sense, shared their spirit of direct grievance-airing, directly feeding into revolutionary discourse. This comparative analysis reveals pamphlets as precision tools in the political toolkit, ideal for targeted campaigns.

Finally, consider the cautionary tale of their misuse. While pamphlets democratize political expression, their lack of gatekeeping can propagate misinformation or hate speech. The anti-Semitic pamphlets of the 19th century, such as those by Édouard Drumont, illustrate how unchecked polemics can poison discourse. Modern digital pamphlets, shared via platforms like Twitter or Telegram, exacerbate this risk, spreading rapidly without fact-checking. To mitigate harm, readers should cross-reference pamphlet claims with credible sources, while writers must balance provocation with responsibility. In this way, pamphlets remain a potent force in French political discourse—but one that demands vigilance.

Colorado's Political Upheaval: Key Events and Shifts in 2023

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

French political pamphlets are short, written works that express political opinions, critiques, or arguments, often in a persuasive or satirical manner. They have been a significant medium for political discourse in France since the Renaissance.

French political pamphlets gained prominence during the 16th century, particularly during the French Wars of Religion and the Enlightenment, as they provided a means to disseminate ideas and challenge authority in a time of political and social upheaval.

Authors of French political pamphlets ranged from intellectuals and writers like Voltaire and Rousseau to anonymous activists. They often used pseudonyms to avoid censorship or persecution, especially during periods of strict political control.

French political pamphlets played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and mobilizing support for causes, such as the French Revolution. They served as tools for propaganda, reform, and resistance, influencing major political and social changes in France.

![Point D'accommodement [a Political Pamphlet] Par Henri-alexandre Audainel... (French Edition)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71Y-Q8GKsNL._AC_UY218_.jpg)