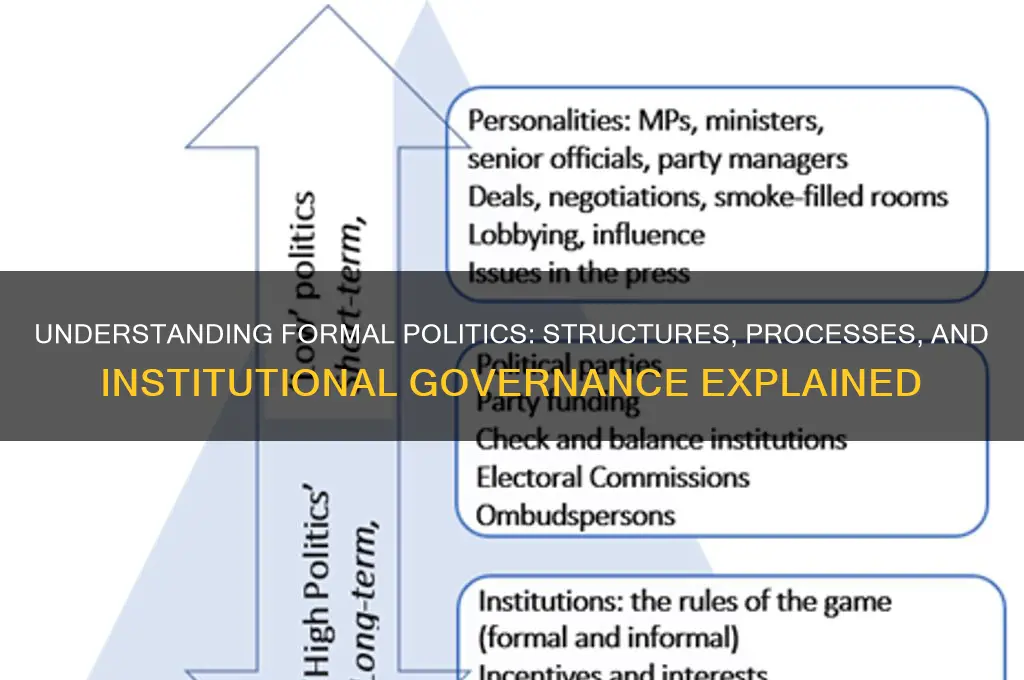

Formal politics refers to the structured and institutionalized processes through which power is exercised, decisions are made, and governance is carried out within a society. It encompasses the official mechanisms of government, including legislative bodies, executive branches, and judicial systems, as well as the rules, procedures, and norms that govern their operations. Formal politics involves the activities of political parties, elections, policy-making, and the administration of public affairs, all of which are conducted within a legal and constitutional framework. Unlike informal politics, which occurs outside these established structures, formal politics is characterized by its adherence to codified laws, hierarchical authority, and formalized roles, making it a central component of organized political systems in modern states.

Explore related products

$9.28 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Political Institutions: Structures like governments, parliaments, and courts that shape formal political systems

- Electoral Processes: Mechanisms for voting, elections, and representation in formal political frameworks

- Legal Frameworks: Laws, constitutions, and regulations governing political behavior and governance

- Political Parties: Organized groups competing for power within formal political systems

- International Diplomacy: Formal interactions and agreements between sovereign states and global organizations

Political Institutions: Structures like governments, parliaments, and courts that shape formal political systems

Formal political systems are the backbone of governance, and their structure is defined by political institutions—entities like governments, parliaments, and courts that establish rules, enforce laws, and mediate conflicts. These institutions are not merely buildings or titles; they are the mechanisms through which power is exercised and decisions are made. For instance, the U.S. Congress, a parliamentary institution, is designed to represent the people’s interests through elected officials, while the Supreme Court acts as a check on legislative and executive powers. Understanding these structures is critical, as they determine how policies are formed, rights are protected, and accountability is maintained.

Consider the role of parliaments in democratic systems. They serve as forums for debate, where diverse viewpoints are aired and compromises are forged. In the United Kingdom, the House of Commons exemplifies this by scrutinizing government actions and passing legislation. However, the effectiveness of parliaments varies. In some countries, they are rubber-stamp bodies with little real power, while in others, they are vibrant centers of political contestation. The structure of a parliament—whether unicameral or bicameral, its electoral system, and its committee system—directly influences its ability to function as a check on executive power and a voice for citizens.

Courts, another cornerstone of formal political systems, play a unique role in upholding the rule of law. They interpret constitutions, resolve disputes, and protect individual rights. The International Court of Justice, for example, settles legal disagreements between nations, while constitutional courts in countries like Germany ensure that laws align with fundamental principles. Yet, the independence of courts is not guaranteed. Political interference, inadequate funding, or lack of public trust can undermine their ability to function effectively. Strengthening judicial institutions requires safeguards like lifetime appointments, transparent selection processes, and robust ethical standards.

Governments, as the executive branch, implement policies and administer public services. Their structure—whether presidential, parliamentary, or hybrid—shapes their relationship with other institutions and their responsiveness to citizens. In France, the semi-presidential system divides power between the president and prime minister, creating a dynamic balance. Conversely, in authoritarian regimes, governments often dominate other institutions, sidelining checks and balances. Effective governance demands not only a clear division of powers but also mechanisms for coordination and accountability.

To illustrate, compare the political institutions of Canada and India. Canada’s parliamentary system emphasizes party discipline and cabinet solidarity, with the Prime Minister holding significant power. India, on the other hand, operates as a federal parliamentary republic with a multi-party system and a strong judiciary. These differences reflect historical contexts and societal needs, highlighting how institutions are tailored to specific environments. For practitioners or observers, studying such variations offers insights into how political systems can be designed or reformed to better serve their populations.

In conclusion, political institutions are not static; they evolve in response to societal changes, technological advancements, and global trends. Strengthening them requires a commitment to transparency, inclusivity, and adaptability. Whether through electoral reforms, judicial independence, or parliamentary modernization, the goal is to create systems that are resilient, responsive, and reflective of the people they serve. By examining these structures critically and comparatively, we can identify best practices and lessons for building more effective formal political systems.

Frankenstein's Political Anatomy: Power, Creation, and Social Responsibility Explored

You may want to see also

Electoral Processes: Mechanisms for voting, elections, and representation in formal political frameworks

Electoral processes are the backbone of formal political systems, providing structured mechanisms for citizens to participate in governance. At their core, these processes encompass voting, elections, and representation, each serving as a critical link between the people and their government. Voting, the most direct form of political participation, allows citizens to express their preferences for candidates, policies, or referendums. Elections, the periodic contests through which representatives are chosen, ensure accountability and legitimacy in governance. Representation, the outcome of these elections, bridges the gap between the electorate and decision-making bodies, ideally reflecting the diverse interests of the population. Together, these mechanisms form a system designed to uphold democratic principles and maintain political stability.

Consider the variety of voting mechanisms employed globally, each with its own strengths and challenges. First-past-the-post systems, used in countries like the United Kingdom and the United States, prioritize simplicity but can lead to disproportionate representation. Proportional representation, common in European nations, ensures that legislative seats more closely align with the popular vote, fostering minority inclusion. Ranked-choice voting, increasingly adopted in local elections, reduces the spoiler effect by allowing voters to rank candidates in order of preference. Each method reflects different societal priorities—whether efficiency, fairness, or inclusivity—and underscores the importance of tailoring electoral systems to specific political contexts.

Elections, however, are not merely technical exercises; they are deeply embedded in the cultural and historical fabric of societies. For instance, the frequency of elections varies widely, with presidential terms ranging from four years in the U.S. to six in France, while parliamentary elections in the UK can be called at any time within a five-year period. Campaign regulations also differ significantly: in Canada, strict spending limits and blackout periods aim to level the playing field, whereas in the U.S., campaign financing is largely unrestricted, often favoring well-funded candidates. These variations highlight how electoral processes are shaped by local norms and values, influencing both their design and outcomes.

Representation, the ultimate goal of electoral processes, remains a complex and often contested concept. While elected officials are expected to act as delegates of their constituents, the reality is often more nuanced. In practice, representatives may balance constituent interests with their own judgment, party loyalties, or broader national concerns. This tension is particularly evident in systems with strong party discipline, where legislators are expected to vote along party lines. To enhance accountability, some countries have introduced mechanisms like recall elections or public consultations, empowering citizens to hold their representatives to higher standards.

In designing or reforming electoral processes, policymakers must navigate trade-offs between competing goals. For example, increasing voter turnout may require lowering barriers to participation, such as introducing early voting or automatic registration, but these measures can also raise concerns about security and fraud. Similarly, while proportional representation promotes diversity, it can lead to fragmented legislatures and unstable coalitions. Practical tips for improving electoral systems include conducting regular audits to ensure transparency, investing in voter education to combat misinformation, and leveraging technology to modernize voting infrastructure. Ultimately, the effectiveness of electoral processes hinges on their ability to balance accessibility, integrity, and representation in ways that strengthen public trust in democratic institutions.

The Spark of Political Purges: Origins and Early Warning Signs

You may want to see also

Legal Frameworks: Laws, constitutions, and regulations governing political behavior and governance

Formal politics operates within a structured legal framework that defines the rules, processes, and boundaries of governance. At its core, this framework consists of laws, constitutions, and regulations designed to ensure stability, accountability, and fairness in political behavior. These instruments are not merely bureaucratic tools but the backbone of any functioning political system, providing clarity on how power is exercised, rights are protected, and disputes are resolved. Without such a framework, politics would devolve into chaos, with no mechanism to enforce agreements or hold leaders accountable.

Consider the constitution, often referred to as the supreme law of the land. It establishes the fundamental principles of governance, outlines the structure of government, and delineates the rights of citizens. For instance, the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1789, not only divides power among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches but also includes the Bill of Rights, safeguarding individual freedoms such as speech, religion, and due process. In contrast, the Constitution of India, the longest in the world, incorporates detailed directives on social justice, reflecting the nation’s unique historical and cultural context. These examples illustrate how constitutions are tailored to address the specific needs and values of their societies.

Laws and regulations, on the other hand, operationalize the principles enshrined in constitutions. They provide the day-to-day rules governing political behavior, from election procedures to public finance management. For example, campaign finance laws in many democracies limit the amount of money individuals or organizations can donate to political candidates, aiming to prevent undue influence. Similarly, environmental regulations mandate how governments and corporations must act to protect natural resources, ensuring that economic development does not come at the expense of ecological sustainability. These laws are not static; they evolve in response to societal changes, technological advancements, and emerging challenges.

However, the effectiveness of legal frameworks depends on their enforcement. Strong institutions, such as independent judiciaries and anticorruption agencies, are essential to ensure that laws are applied consistently and impartially. In countries where these institutions are weak, legal frameworks often exist in name only, with powerful actors circumventing rules without consequence. For instance, while many nations have laws against bribery, their impact varies widely depending on the capacity and integrity of enforcement bodies. This underscores the importance of not just creating laws but also building the infrastructure to uphold them.

In conclusion, legal frameworks are the scaffolding of formal politics, providing structure and predictability in an inherently complex arena. They reflect a society’s values, address its challenges, and guide its aspirations. Yet, their success hinges on more than just their content—it requires robust institutions, public trust, and a commitment to the rule of law. As political systems navigate an increasingly interconnected and rapidly changing world, the adaptability and resilience of these frameworks will be tested, making their thoughtful design and diligent enforcement more critical than ever.

Spartan Politics: Unveiling the Unique Governance of Ancient Sparta

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political Parties: Organized groups competing for power within formal political systems

Political parties are the engines of formal political systems, structured to mobilize resources, articulate ideologies, and compete for control of governance. Unlike informal political movements, which may lack clear hierarchies or long-term goals, parties are institutionalized entities with defined leadership, membership, and policy platforms. Their primary function is to aggregate interests, translate them into actionable agendas, and secure electoral mandates to implement those agendas. For instance, the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States exemplify this model, each with distinct organizational structures, fundraising mechanisms, and voter outreach strategies. Without such organized groups, formal politics would devolve into fragmented, chaotic contests of individual ambitions.

Consider the lifecycle of a political party: formation, consolidation, and competition. Formation often begins with a core group identifying a gap in representation—whether ideological, demographic, or policy-driven. Consolidation involves building a grassroots base, drafting a constitution, and registering within legal frameworks. Competition then unfolds through campaigns, debates, and elections, where parties deploy tactics ranging from door-to-door canvassing to multimillion-dollar media campaigns. In Germany, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Social Democratic Party (SPD) have dominated post-war politics by mastering this cycle, adapting their platforms to shifting voter priorities while maintaining organizational discipline. This structured approach contrasts sharply with movements like the Arab Spring, which, while powerful, lacked the institutional backbone to transition into stable governing forces.

A critical caution emerges when parties prioritize power over principle. The allure of winning elections can lead to ideological dilution, as parties moderate stances to appeal to swing voters. For example, the Labour Party in the UK shifted from its socialist roots under Tony Blair’s "New Labour" to capture centrist support, alienating its traditional base. Similarly, in India, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been accused of leveraging nationalist rhetoric to consolidate power, sometimes at the expense of minority rights. This tension between pragmatism and ideology underscores the challenge of balancing electoral success with policy integrity. Parties must navigate this trade-off carefully, or risk becoming hollow vessels of power rather than vehicles of meaningful change.

To maximize their impact, political parties should adopt a three-pronged strategy: clarify their unique value proposition, invest in data-driven campaigning, and foster internal democracy. First, a clear ideological stance helps voters understand what the party stands for, reducing ambiguity. Second, leveraging data analytics—as seen in Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign, which used microtargeting to identify and mobilize key voter segments—can optimize resource allocation. Third, internal democracy, such as open primaries or member-driven policy development, ensures that parties remain responsive to their base. For instance, Spain’s Podemos party uses digital platforms to allow members to vote on candidates and policies, enhancing transparency and engagement. These steps not only strengthen a party’s competitive edge but also reinforce its legitimacy within the formal political system.

Ultimately, political parties are indispensable to formal politics, serving as bridges between citizens and state institutions. Their ability to organize, mobilize, and govern hinges on their capacity to balance ambition with accountability. While their competitive nature can lead to polarization or gridlock—as seen in the U.S. Congress—it also fosters innovation and representation. The takeaway is clear: parties are not merely tools for power; they are the scaffolding of democratic governance. By understanding their mechanics and challenges, citizens can better engage with—or reform—these systems to ensure they serve the public good.

How Historical Events and Social Movements Shaped National Politics

You may want to see also

International Diplomacy: Formal interactions and agreements between sovereign states and global organizations

International diplomacy is the backbone of formal politics on the global stage, where sovereign states and international organizations engage in structured dialogues and binding agreements to address shared challenges and conflicts. Unlike informal diplomacy, which relies on personal relationships and backchannel communications, formal diplomacy operates within established frameworks, such as treaties, summits, and multilateral institutions. These mechanisms ensure predictability, accountability, and legitimacy in international relations, even when tensions run high. For instance, the United Nations General Assembly provides a platform for all member states to voice their concerns and negotiate resolutions, while the World Trade Organization enforces rules governing global commerce. Without these formal structures, international cooperation would devolve into chaos, leaving critical issues like climate change, nuclear proliferation, and humanitarian crises unaddressed.

Consider the process of treaty ratification, a cornerstone of formal diplomacy. When two or more nations negotiate a treaty, they follow a meticulous sequence: drafting, signing, ratification, and implementation. Each step involves legal scrutiny, legislative approval (in democratic systems), and public transparency. The Paris Agreement on climate change exemplifies this process, with 196 parties committing to limit global warming to well below 2°C. However, formal agreements are not without challenges. Ratification can stall due to domestic political opposition, as seen with the U.S. Senate’s rejection of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. Moreover, enforcement mechanisms often lack teeth, relying on peer pressure or economic sanctions rather than military force. Despite these limitations, treaties remain essential tools for codifying international norms and fostering collective action.

A comparative analysis of formal diplomacy reveals its adaptability across diverse contexts. Bilateral agreements, such as the 2020 Abraham Accords normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, demonstrate how direct negotiations can resolve long-standing conflicts. In contrast, multilateral forums like the G20 address global economic issues through consensus-building among major powers and emerging economies. Regional organizations, such as the African Union or ASEAN, tailor diplomatic efforts to local priorities, balancing sovereignty with cooperation. Each approach has its strengths and weaknesses: bilateral diplomacy is swift but limited in scope, while multilateralism is inclusive but slow. The choice of format depends on the issue at hand, the parties involved, and the desired outcome.

To engage effectively in formal diplomacy, stakeholders must navigate a complex web of protocols, cultural nuances, and power dynamics. Ambassadors, for instance, must master the art of negotiation, balancing national interests with the need for compromise. Global organizations, meanwhile, must ensure inclusivity, avoiding dominance by major powers. Practical tips include: preparing thoroughly for negotiations by researching counterparts’ priorities, leveraging data and evidence to strengthen arguments, and building coalitions to amplify influence. For instance, small island nations have successfully advocated for climate action by uniting under the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), despite their limited individual clout. Such strategies highlight the importance of skill, persistence, and creativity in formal diplomatic settings.

Ultimately, formal diplomacy is not a panacea but a vital mechanism for managing an interconnected world. Its success hinges on the willingness of states and organizations to engage in good faith, uphold commitments, and adapt to evolving challenges. As global threats grow more complex—from pandemics to cyber warfare—the need for robust formal frameworks has never been greater. By understanding its principles, processes, and pitfalls, actors can harness the power of formal diplomacy to build a more stable and equitable international order. After all, in a world of competing interests, the ability to negotiate, compromise, and cooperate is not just a skill—it’s a necessity.

Understanding Political Weighting: A Key Tool in Polling and Elections

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Formal politics refers to the structured and institutionalized processes through which decisions are made and power is exercised within a society, typically involving governments, political parties, and official organizations.

Formal politics operates within established rules, laws, and institutions, while informal politics involves unofficial, often behind-the-scenes influence, such as lobbying, personal networks, or community activism.

Key components include legislative bodies (e.g., parliaments), executive branches (e.g., presidents or prime ministers), judicial systems, political parties, and electoral processes.

Formal politics provide a framework for legitimate decision-making, ensure accountability, protect rights, and allow citizens to participate in governance through voting and representation.

Yes, formal politics can exist in authoritarian or totalitarian regimes, but they often lack transparency, citizen participation, and checks on power, serving primarily to maintain control by the ruling elite.