The development of American political parties traces its origins to the late 18th century, emerging as a response to the ideological divisions and political debates that followed the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1787. Initially, the Founding Fathers, including George Washington, were wary of political factions, viewing them as threats to unity and stability. However, by the 1790s, the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, formalized the nation’s first political parties. This period marked the beginning of organized party politics in America, as these groups rallied around differing visions of governance, economic policy, and the role of the federal government. The year 1796 is often cited as a pivotal moment, as it saw the first contested presidential election between these emerging parties, solidifying their role in American political life.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Early Factions in the 1790s

The 1790s marked a pivotal decade in American political history, as the young nation grappled with the formation of its first distinct political factions. These early divisions laid the groundwork for the two-party system that would dominate American politics for centuries. The Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republicans, championed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, emerged as the primary contenders, each advocating for contrasting visions of the nation’s future. Their disagreements centered on issues such as the role of the federal government, economic policy, and foreign relations, setting the stage for enduring political debates.

Consider the Federalist Party, which coalesced around Hamilton’s vision of a strong central government and a robust national economy. Federalists championed the creation of a national bank, protective tariffs, and the assumption of state debts by the federal government. These policies, outlined in Hamilton’s economic plan, aimed to stabilize the nation’s finances and foster industrial growth. However, critics argued that such measures favored the wealthy elite and threatened states’ rights. The Federalists’ pro-British stance during the French Revolution further alienated those who feared the resurgence of monarchical influence in America.

In contrast, the Democratic-Republican Party, often referred to as Jeffersonians, advocated for a more limited federal government and emphasized agrarian interests. Jefferson and Madison viewed Hamilton’s policies as a dangerous overreach, warning that they would undermine individual liberties and concentrate power in the hands of a few. They championed states’ rights, strict interpretation of the Constitution, and a foreign policy of neutrality. The Democratic-Republicans’ populist appeal resonated with farmers and rural voters, who felt marginalized by Federalist policies. Their victory in the 1800 election marked a significant shift in American politics, demonstrating the power of organized opposition.

A key example of the tension between these factions was the debate over the Jay Treaty in 1795. Negotiated by John Jay, the treaty aimed to resolve lingering issues with Britain but was seen by many Jeffersonians as a betrayal of American interests. Federalists supported the treaty as a pragmatic solution to avoid war, while Democratic-Republicans denounced it as a sellout to British influence. This controversy highlighted the deepening ideological divide and the emergence of partisan politics in the early republic.

Understanding these early factions provides insight into the enduring themes of American politics: the balance between federal and state power, the role of government in the economy, and the nation’s place in the world. The 1790s were not just a period of political experimentation but a crucible in which the principles of American democracy were forged. By studying this era, we can better appreciate the origins of the partisan dynamics that continue to shape the United States today.

Lei Sharsh-Davis Political Party Affiliation: Unveiling Her Political Leanings

You may want to see also

Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans

The development of American political parties began in the 1790s, with the emergence of the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans as the first major factions. These parties, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, respectively, defined early American politics through their contrasting visions of government, economy, and society. Their rivalry not only shaped the nation’s foundational policies but also established a partisan framework that persists in modern politics.

Consider the Federalist Party, which dominated the 1790s under President George Washington and later John Adams. Federalists advocated for a strong central government, believing it essential for national stability and economic growth. They championed Hamilton’s financial plans, including the establishment of a national bank, assumption of state debts, and excise taxes. These policies aimed to foster industrial development and solidify the nation’s creditworthiness. However, their support for the Alien and Sedition Acts in the late 1790s alienated many, as these laws restricted civil liberties and targeted political dissenters. The Federalists’ pro-British stance during the Quasi-War with France further eroded their popularity, leading to their decline by the early 1800s.

In contrast, the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Jefferson and James Madison, emerged as a counterforce to Federalist policies. They championed states’ rights, agrarian interests, and a limited federal government, viewing the Federalists’ centralization as a threat to individual liberty. Jefferson’s election in 1800 marked a pivotal shift, as his party dismantled Federalist programs, reduced the national debt, and expanded westward with the Louisiana Purchase. Democratic-Republicans also opposed standing armies and navies, favoring militias instead. Their emphasis on rural democracy and opposition to elitism resonated with the majority of Americans, ensuring their dominance for decades.

A key takeaway from this rivalry is how it framed enduring debates in American politics: centralization vs. states’ rights, industrialism vs. agrarianism, and interventionism vs. isolationism. The Federalists’ legacy is evident in modern conservative support for strong federal institutions and economic intervention, while the Democratic-Republicans’ ideals align with contemporary progressive and libertarian calls for limited government and individual freedoms. Understanding this early divide provides context for today’s political polarization, as many current issues echo these foundational disagreements.

Practical tip: To grasp the impact of these parties, examine primary sources like the Federalist Papers and Jefferson’s inaugural addresses. These documents reveal the philosophical and practical differences that defined early American politics and continue to influence political discourse. By studying these origins, one can better navigate the complexities of modern partisan debates.

Do City Council Members Have Political Party Affiliations?

You may want to see also

Era of Good Feelings (1816-1824)

The Era of Good Feelings, spanning from 1816 to 1824, is often remembered as a period of national unity and reduced partisan conflict in American politics. This era emerged in the aftermath of the War of 1812, which had fostered a sense of national pride and purpose. With the Federalist Party in decline due to its opposition to the war, the Democratic-Republican Party, led by James Monroe, dominated the political landscape. This apparent unity, however, masked underlying tensions that would later reshape the American political party system.

Analytically, the Era of Good Feelings was less about genuine political harmony and more about the temporary absence of strong opposition. Monroe’s presidency saw the Democratic-Republican Party operate with little resistance, as the Federalists failed to regain their former influence. This period is often cited as a time when party politics seemed to fade into the background, but it was, in reality, a lull before the storm. Regional differences, particularly over issues like tariffs and states’ rights, were simmering beneath the surface. These divisions would eventually give rise to new political alignments, such as the emergence of the Whig Party and the Second Party System in the late 1820s and 1830s.

Instructively, understanding this era requires examining its key events and figures. Monroe’s reelection in 1820, for instance, was uncontested, earning it the nickname "The Era of Good Feelings." His domestic tour in 1817 further symbolized national unity, as he was greeted with enthusiasm across the country. However, practical lessons from this period highlight the importance of recognizing latent political tensions. For example, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which temporarily resolved the issue of slavery in new states, demonstrated how regional interests could fracture even during times of apparent unity.

Persuasively, the Era of Good Feelings serves as a cautionary tale about the illusion of political consensus. While the absence of strong opposition can create the appearance of stability, it often fails to address deeper ideological and regional divides. This era reminds us that true political development requires engagement with differing viewpoints rather than their suppression. By the mid-1820s, as these divisions resurfaced, the American political landscape began to realign, setting the stage for the more contentious party politics of the Jacksonian era.

Comparatively, the Era of Good Feelings contrasts sharply with other periods of American political development. Unlike the fiercely partisan 1790s, when Federalists and Democratic-Republicans clashed over the nation’s future, this era saw a temporary pause in such conflicts. However, it also differs from later periods, such as the 1850s, when partisan divisions over slavery led to the collapse of the Second Party System. This comparison underscores the unique nature of the Era of Good Feelings as a brief interlude of political calm before the resurgence of party competition.

In conclusion, the Era of Good Feelings was a pivotal yet deceptive moment in the development of American political parties. While it appeared to signify national unity, it was, in fact, a period of latent tension and transformation. By examining its specifics—Monroe’s uncontested reelection, the Missouri Compromise, and the decline of the Federalists—we gain insight into the complexities of political evolution. This era teaches us that true political stability requires addressing underlying divisions rather than merely masking them, a lesson that remains relevant in understanding party dynamics today.

Harry Hull's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Loyalty

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Second Party System Emergence (1828-1854)

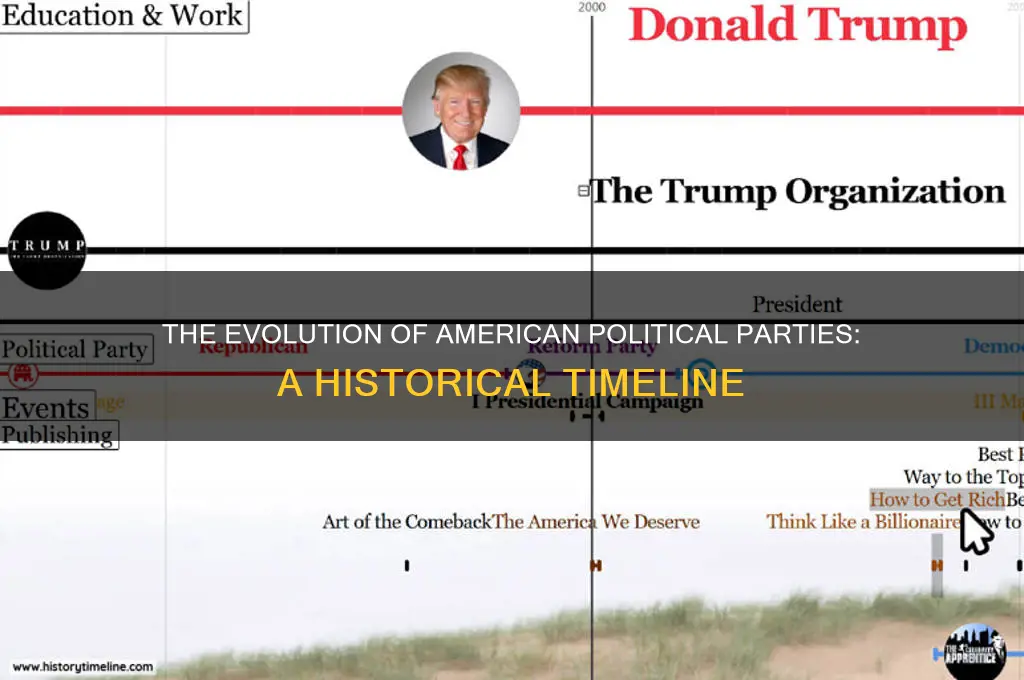

The Second Party System, emerging between 1828 and 1854, marked a transformative era in American political history, characterized by the rise of the Democratic Party and the Whig Party. This period followed the collapse of the First Party System, dominated by the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, and reflected the nation’s shifting demographics, economic interests, and ideological divides. The 1828 election of Andrew Jackson as president symbolized the beginning of this era, as his Democratic Party championed states’ rights, limited federal government, and the expansion of white male suffrage. In contrast, the Whigs, led by figures like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, advocated for national economic development, internal improvements, and a stronger federal role.

To understand the dynamics of this system, consider the key issues that defined it. The Democrats appealed to farmers, laborers, and the growing urban working class, while the Whigs attracted businessmen, industrialists, and those favoring modernization. The era saw intense political mobilization, with both parties building extensive networks of newspapers, rallies, and local organizations to engage voters. For instance, the 1840 presidential campaign, known as the “Log Cabin and Hard Cider” campaign, exemplified the Whigs’ use of symbolism and grassroots tactics to challenge Jacksonian democracy. This period also witnessed the emergence of third parties, such as the Liberty Party, which focused on the abolition of slavery, foreshadowing the deeper divides to come.

Analyzing the Second Party System reveals its role as a bridge between the early republic and the Civil War era. It grappled with issues like westward expansion, banking, and tariffs, but its inability to resolve the slavery question ultimately led to its downfall. The Compromise of 1850 temporarily eased tensions, but the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 shattered the fragile balance, leading to the collapse of the Whig Party and the rise of the Republican Party. This transition underscores the system’s limitations in addressing moral and sectional conflicts, which would soon dominate American politics.

For those studying this period, a comparative approach can illuminate its significance. Unlike the First Party System, which was more elite-driven, the Second Party System thrived on mass participation and ideological polarization. Practical tips for understanding its legacy include examining primary sources like party platforms, campaign materials, and political cartoons, which reveal the era’s rhetoric and strategies. Additionally, mapping the geographic distribution of party support—Democrats in the South and West, Whigs in the North and East—provides insight into the regional divides that shaped the nation’s future.

In conclusion, the Second Party System was a critical chapter in the development of American political parties, reflecting the nation’s evolving identity and challenges. Its rise and fall offer lessons on the interplay of democracy, sectionalism, and ideology. By studying this era, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of party politics and their enduring impact on the United States.

Tom Hanks' Political Views: Uncovering the Actor's Beliefs and Activism

You may want to see also

Civil War Impact on Parties (1860s)

The American Civil War of the 1860s was a crucible that reshaped the nation’s political landscape, forcing parties to redefine their identities and alliances. Before the war, the Democratic Party dominated the South, advocating for states’ rights and the expansion of slavery, while the Whig Party, and later the Republican Party, held sway in the North, focusing on economic modernization and the containment of slavery. The war’s onset fractured these alignments, as the issue of slavery became inescapable. The Republican Party, led by Abraham Lincoln, emerged as the primary force opposing the Confederacy, while the Democrats split between War Democrats, who supported the Union, and Peace Democrats (Copperheads), who sought reconciliation with the South. This period marked the beginning of the Republicans’ rise as a dominant national party, while the Democrats struggled to reconcile their pro-slavery legacy with a post-war nation.

Consider the immediate aftermath of the war: the Republican Party solidified its position by championing Reconstruction policies aimed at protecting the rights of freed slaves and rebuilding the South. The passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, which abolished slavery, granted citizenship, and ensured voting rights for African Americans, was a direct result of Republican dominance. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party, particularly in the South, resisted these changes, laying the groundwork for the Solid South—a region where Democrats would dominate for nearly a century. This realignment was not just ideological but also geographic, as the South’s shift to the Democratic Party and the North’s alignment with the Republicans created a sectional divide that persisted well into the 20th century.

A comparative analysis reveals how the Civil War accelerated the decline of third parties, such as the Constitutional Union Party, which had briefly sought to bridge the North-South divide by avoiding the slavery issue altogether. By 1864, the National Union Party—a temporary coalition of Republicans and War Democrats—nominated Lincoln for reelection, signaling the consolidation of the two-party system. This shift marginalized smaller parties, as the war’s binary nature (Union vs. Confederacy) mirrored the political binary of Republicans vs. Democrats. The war’s impact on party structure was thus twofold: it strengthened the Republicans while forcing the Democrats to adapt, often at the cost of internal cohesion.

Practically speaking, understanding this period offers lessons for modern political strategists. The Civil War era demonstrates how external crises can force parties to clarify their stances on divisive issues, often at the risk of alienating factions. For instance, the Democrats’ inability to unite on the issue of slavery led to long-term regional and ideological fragmentation. Conversely, the Republicans’ clear stance on preserving the Union and ending slavery earned them enduring support. Today, parties facing polarizing issues like climate change or immigration could study this era to see how principled stances, though risky, can reshape political landscapes.

In conclusion, the Civil War’s impact on American political parties was transformative, reshaping their ideologies, geographic bases, and national influence. It solidified the Republicans as the party of the North and eventual champions of civil rights, while the Democrats became the party of the South, grappling with their pro-slavery past. This period underscores the enduring power of crisis to redefine political identities and the importance of clarity in times of national upheaval. By examining the 1860s, we gain insight into how parties evolve under pressure—a lesson as relevant today as it was then.

Understanding the Left Party: Political Ideologies and Their Global Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The development of American political parties began in the early 1790s, with the emergence of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties during George Washington's presidency.

Key figures included Alexander Hamilton, who led the Federalists, and Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who founded the Democratic-Republican Party.

The First Party System, established in the 1790s, featured the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party as the dominant political forces in early American politics.