Political machines, which dominated urban American politics in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were often criticized for their corrupt practices. These organizations, led by powerful bosses like Tammany Hall's William Tweed, operated by trading favors, jobs, and services for political support, creating a system of patronage that blurred the lines between public service and personal gain. While they provided essential resources to immigrant communities and the working class, their methods frequently involved voter fraud, bribery, and kickbacks, raising questions about the integrity of the democratic process. Critics argued that political machines undermined good governance by prioritizing loyalty over competence and perpetuating a cycle of dependency. However, supporters contended that they filled a void left by unresponsive governments, offering tangible benefits to marginalized groups. Ultimately, the legacy of political machines remains complex, reflecting both their contributions to social welfare and their undeniable association with corruption.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Patronage System | Political machines often distributed government jobs and contracts in exchange for political support, leading to corruption and inefficiency. |

| Voter Fraud | Machines frequently engaged in voter intimidation, ballot stuffing, and repeat voting to ensure electoral victories. |

| Bribery and Kickbacks | Officials and machine operatives accepted bribes from businesses and individuals in exchange for favorable treatment or contracts. |

| Control of Local Government | Machines dominated city councils, police departments, and other local institutions, often using them to further their own interests. |

| Lack of Transparency | Decision-making processes were opaque, with deals and agreements made behind closed doors, fostering corruption. |

| Exploitation of Immigrants | Machines often relied on immigrant communities for votes, offering patronage jobs in exchange for political loyalty, sometimes exploiting their vulnerabilities. |

| Monopoly on Power | Machines maintained long-term control over cities, stifling political competition and perpetuating corrupt practices. |

| Connection to Organized Crime | Some machines had ties to organized crime, allowing illegal activities to flourish in exchange for financial or political support. |

| Public Works Mismanagement | Funds for public projects were often misappropriated or used to benefit machine-aligned businesses rather than the public. |

| Resistance to Reform | Machines actively opposed reforms aimed at increasing transparency, accountability, and fair governance. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Bosses and Patronage Systems

Political machines, often led by powerful bosses, thrived on patronage systems that exchanged favors for loyalty. These bosses controlled jobs, contracts, and services, wielding immense influence over local politics. While critics labeled this system corrupt, it functioned as a survival mechanism in impoverished urban areas, providing resources to marginalized communities neglected by mainstream institutions. For instance, Tammany Hall in New York City under Boss Tweed distributed food, coal, and even legal aid to immigrants, ensuring their votes in return. This symbiotic relationship highlights the blurred line between corruption and community support.

To understand the mechanics, consider the step-by-step process of patronage: First, the boss secured control over government appointments, often through political victories. Second, they distributed these positions to loyal followers, creating a network of dependents. Third, these appointees funneled resources back to the boss, who then redistributed them to constituents. This cycle solidified the boss’s power while addressing immediate community needs. However, the system’s inherent lack of transparency and accountability often led to embezzlement, as seen in the Tweed Ring’s notorious fraud cases.

A comparative analysis reveals that patronage systems were not inherently corrupt but became so when exploited for personal gain. In contrast to modern merit-based hiring, patronage prioritized loyalty over competence, leading to inefficiencies. Yet, it filled a void in an era before social welfare programs, acting as a proto-safety net. For example, Chicago’s Democratic machine under Mayor Daley provided jobs to thousands during the Great Depression, though often at the cost of public funds. This duality—serving the community while exploiting resources—defines the legacy of bosses and patronage.

To mitigate corruption in such systems, practical reforms are essential. First, implement transparent hiring processes that balance merit and community needs. Second, establish independent oversight bodies to monitor resource allocation. Third, invest in public education to reduce dependency on political machines. For instance, the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 aimed to dismantle patronage by introducing competitive exams for federal jobs. While not a panacea, such measures can curb abuses while preserving the system’s community-oriented aspects.

In conclusion, bosses and patronage systems were neither wholly corrupt nor entirely benevolent. They emerged as responses to societal failures, offering support to the vulnerable while breeding opportunism. By studying their mechanisms and consequences, we can design modern political structures that prioritize fairness without sacrificing community welfare. The key lies in balancing power with accountability, ensuring that patronage serves the people, not the other way around.

Understanding FSA Politics: Key Concepts, Players, and Implications Explained

You may want to see also

Voter Fraud and Intimidation

To understand the mechanics of voter intimidation, consider the role of "repeaters"—individuals paid to vote multiple times under different names. These operatives were often provided with pre-marked ballots or coached to vote in specific precincts where machine-friendly officials would turn a blind eye. Intimidation was equally brazen: voters might face physical violence, loss of jobs, or eviction if they refused to comply. In immigrant-heavy wards, language barriers were exploited, with machine representatives offering "assistance" that effectively dictated votes. These methods were not merely theoretical; they were documented in congressional investigations and exposés, such as those by journalists like Lincoln Steffens during the Progressive Era.

The impact of these practices extended beyond individual elections, eroding public trust in democratic institutions. Machines justified their actions as necessary to deliver services to constituents, but the cost was the corruption of the electoral process itself. For example, in Chicago under Mayor Richard J. Daley, allegations of voter fraud persisted into the mid-20th century, with reports of "ghost voting" and manipulated vote counts. Such tactics disproportionately affected marginalized communities, who were often dependent on machine patronage for basic needs, creating a cycle of dependency and exploitation.

Addressing voter fraud and intimidation requires a multi-pronged approach. Historically, reforms like the introduction of secret ballots, voter registration laws, and federal oversight (e.g., the Voting Rights Act of 1965) have been effective in curbing these practices. Modern solutions include biometric voter verification, transparent vote counting, and penalties for coercion. However, vigilance is essential; even today, allegations of voter suppression and irregularities persist, reminding us that the legacy of political machines lives on in subtler, yet equally damaging, forms.

In conclusion, voter fraud and intimidation were not anomalies but systemic features of political machines. Their methods were as inventive as they were destructive, undermining the very foundation of democracy. By studying these historical practices, we gain insights into the importance of safeguarding electoral integrity and the ongoing need to protect the rights of every voter. The fight against corruption in this realm is far from over, but understanding its roots is the first step toward meaningful reform.

Hate Crimes as Political Tools: Power, Division, and Social Control

You may want to see also

Bribery and Kickbacks

The mechanics of kickbacks within political machines were equally insidious. Contractors and businesses seeking government contracts would pay a percentage of their profits back to the machine, ensuring they remained in favor for future deals. This practice was particularly prevalent in urban infrastructure projects, where machines controlled the allocation of contracts for roads, bridges, and public buildings. For example, in Chicago during the late 19th century, the Democratic machine under Mayor Richard J. Daley routinely demanded kickbacks from construction firms, funneling the money back into the machine’s coffers to maintain its dominance. Such arrangements not only enriched machine operatives but also inflated project costs, burdening taxpayers.

To combat bribery and kickbacks, reformers in the early 20th century pushed for civil service reforms, such as the Pendleton Act of 1883, which aimed to replace patronage-based hiring with merit-based systems. However, these measures were often circumvented by machines that adapted their tactics. For instance, machines would still control the appointment of examiners for civil service tests, ensuring their allies passed. Practical steps to address modern-day equivalents include strengthening whistleblower protections, mandating transparent procurement processes, and imposing stricter penalties for corruption. Individuals can contribute by reporting suspicious activities to oversight bodies and supporting candidates committed to ethical governance.

Comparatively, while bribery and kickbacks are illegal today, their legacy persists in softer forms of influence-peddling, such as campaign contributions and lobbying. The distinction between a legitimate donation and a bribe can be murky, particularly when donors expect favorable policies in return. For example, a developer contributing to a politician’s campaign might later receive zoning approvals, raising questions about quid pro quo arrangements. To navigate this gray area, citizens should advocate for campaign finance reforms, such as caps on donations and real-time disclosure requirements, to reduce the potential for corruption.

Ultimately, the prevalence of bribery and kickbacks in political machines underscores the corrosive effect of transactional politics on democratic institutions. While machines provided tangible benefits to marginalized communities, their reliance on corruption undermined public trust and distorted governance. By studying these historical practices, we can better identify and address contemporary forms of political malfeasance. Practical takeaways include supporting anti-corruption legislation, engaging in local politics to hold leaders accountable, and educating communities about the dangers of quid pro quo arrangements. Only through vigilance and systemic reform can we mitigate the enduring legacy of bribery and kickbacks in politics.

Inflation's Dual Nature: Economic Forces vs. Political Decisions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Control of Local Governments

Political machines often exerted control over local governments through a combination of patronage, coercion, and strategic alliances, creating systems that blurred the lines between public service and private gain. By dominating city councils, police departments, and public works, these machines could allocate resources, enforce laws, and shape policies to benefit their leaders and supporters. For instance, the Tammany Hall machine in 19th-century New York City controlled municipal jobs, granting positions to loyalists while sidelining opponents, effectively turning public offices into extensions of the machine’s power structure.

To understand how this control operated, consider the mechanics of patronage. Machines would distribute government jobs, contracts, and favors to their followers, ensuring loyalty and dependence. In return, these beneficiaries would mobilize voters, monitor neighborhoods, and even intimidate opponents during elections. This quid pro quo system allowed machines to dominate local politics, often at the expense of transparency and accountability. For example, in Chicago during the early 20th century, the Democratic machine under Mayor Richard J. Daley controlled hiring in city departments, cementing its grip on power by rewarding supporters with jobs and contracts.

However, the control of local governments by political machines was not inherently corrupt in every case. Some machines delivered tangible benefits to marginalized communities, such as immigrants or the working class, who were often ignored by mainstream political parties. Tammany Hall, for instance, provided social services, legal aid, and employment opportunities to Irish immigrants, earning their loyalty and support. This raises a critical question: does the end justify the means? While the methods of control were often questionable, the outcomes occasionally addressed real needs, complicating the narrative of outright corruption.

To dismantle or mitigate the control of local governments by political machines, several strategies can be employed. First, implementing civil service reforms to replace patronage-based hiring with merit-based systems can reduce machine influence. Second, increasing transparency in government contracts and spending can limit opportunities for graft. Third, empowering independent media and watchdog organizations can expose abuses of power. For instance, the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 in the U.S. aimed to curb patronage by introducing competitive exams for federal jobs, a model that could be adapted for local governments.

Ultimately, the control of local governments by political machines highlights the tension between efficiency and ethics in governance. While machines could deliver results quickly and effectively, their reliance on patronage and coercion often undermined democratic principles. By studying these historical examples, modern policymakers can design systems that balance responsiveness to local needs with safeguards against corruption, ensuring that public institutions serve the common good rather than private interests.

What Excites Political Scientists: Theories, Trends, and Transformative Ideas

You may want to see also

Reform Movements and Scandals

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of political machines, often accused of corruption, which controlled major U.S. cities like New York, Chicago, and Boston. These machines, led by bosses such as Tammany Hall’s William Tweed, traded favors, jobs, and services for votes, creating a system of dependency and patronage. While they provided essential resources to immigrants and the poor, their methods frequently crossed ethical and legal boundaries, sparking widespread public outrage and reform movements.

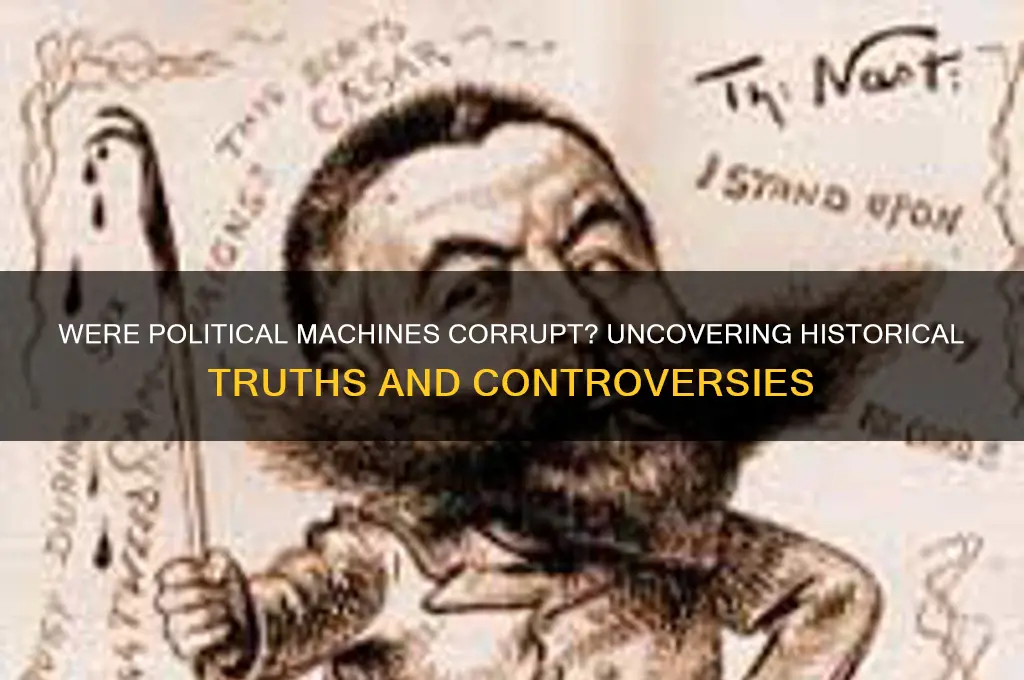

One of the most effective strategies against political machines was the exposure of scandals, which galvanized public opinion and fueled reform efforts. Investigative journalists, known as muckrakers, played a pivotal role in uncovering corruption. For instance, Lincoln Steffens exposed machine politics in *The Shame of the Cities* (1904), detailing how bosses like Tweed embezzled millions through fraudulent contracts. Similarly, the Tweed Ring scandal in the 1870s, revealed through Thomas Nast’s cartoons in *Harper’s Weekly*, led to Tweed’s conviction and the temporary weakening of Tammany Hall. These exposés not only informed the public but also pressured governments to act.

Reform movements emerged as a direct response to machine corruption, advocating for transparency, accountability, and ethical governance. The Progressive Era (1890s–1920s) saw the rise of initiatives like civil service reform, which replaced patronage-based hiring with merit-based systems. The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 was a landmark in this effort, reducing the machines’ control over government jobs. Additionally, direct primaries and secret ballots were introduced to minimize voter intimidation and fraud, tools often employed by machines to maintain power.

Despite these reforms, political machines adapted, finding new ways to exploit the system. For example, Chicago’s Daley Machine in the mid-20th century continued to wield influence through patronage and favoritism, even as legal constraints tightened. This highlights a critical takeaway: reform is an ongoing process, not a one-time solution. Scandals and exposés remain essential tools for holding power accountable, but they must be paired with structural changes to prevent corruption from reemerging.

To combat machine corruption today, citizens and policymakers can take specific steps. Strengthening ethics laws, increasing transparency in campaign financing, and empowering independent investigative bodies are practical measures. For instance, cities like New York have established Conflict of Interest Boards to monitor public officials. Additionally, civic education can help voters recognize and resist machine tactics, such as vote buying or coercion. By learning from historical scandals and reforms, modern societies can build more resilient democratic institutions.

Mastering Polite Requests: The Power of 'Could You' in Communication

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political machines were not inherently corrupt, but they often engaged in practices like patronage, vote buying, and graft to maintain power and control.

While many political machines engaged in illegal activities, some operated within the law, focusing on delivering services and jobs to their constituents in exchange for political loyalty.

Political machines thrived in urban areas due to high population density and the need for centralized services, but corruption was not exclusive to cities; it depended on the leaders and practices of the machine.

Yes, political machines often manipulated elections through voter fraud, intimidation, and ballot stuffing to ensure their candidates won, undermining democratic integrity.

No, many members of political machines were ordinary citizens seeking jobs or services, while corruption was typically concentrated among the machine’s leaders and key operatives.