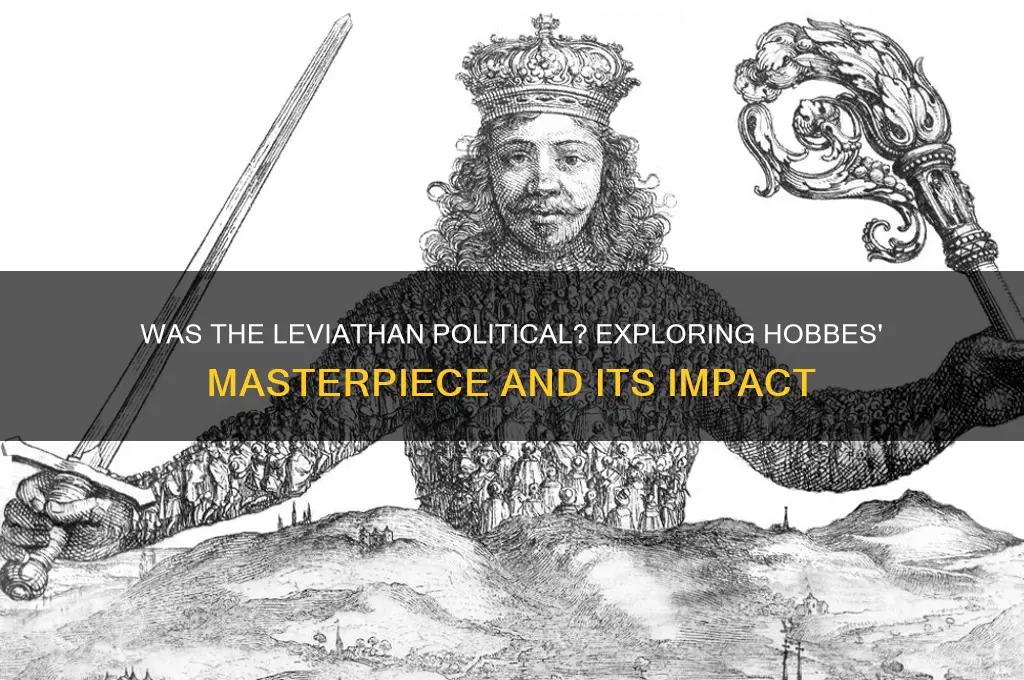

The question of whether Thomas Hobbes's *Leviathan* is fundamentally political is central to understanding its enduring impact on political philosophy. Published in 1651, *Leviathan* presents a comprehensive framework for understanding the nature of human society, the origins of the state, and the necessity of absolute sovereignty to prevent the war of all against all in the state of nature. Hobbes's arguments are deeply political, as they address the legitimacy of authority, the social contract, and the role of the state in securing peace and order. By grounding his analysis in a materialist and mechanistic worldview, Hobbes challenges traditional religious and moral justifications for power, instead advocating for a secular, rational basis for political organization. Thus, *Leviathan* is not merely a philosophical treatise but a profoundly political work that reshaped the way thinkers and statesmen conceptualize governance and the relationship between individuals and the state.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Author | Thomas Hobbes |

| Publication Year | 1651 |

| Central Theme | Social Contract Theory |

| Political Philosophy | Absolutism |

| State of Nature | War of all against all (Bellum omnium contra omnes) |

| Purpose of Government | To maintain order and prevent chaos |

| Sovereignty | Undivided and absolute |

| Rights of Subjects | Limited; primarily the right to self-preservation |

| Role of Law | To enforce peace and security |

| Religion and State | Subordination of religion to state authority |

| Human Nature | Selfish and competitive |

| Criticism | Accused of justifying tyranny and suppressing individual freedoms |

| Influence | Foundation of modern political philosophy and Western political thought |

| Key Concept | Leviathan as a commonwealth or state with supreme authority |

| Historical Context | Written during the English Civil War (1642–1651) |

| Modern Relevance | Debates on state power, individual rights, and social order |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Hobbes’s Social Contract Theory

Thomas Hobbes' *Leviathan* is a cornerstone of political philosophy, and his social contract theory remains a provocative framework for understanding the origins of political authority. At its core, Hobbes argues that individuals, driven by self-preservation in a hypothetical "state of nature," agree to surrender their natural freedoms to a sovereign power in exchange for security and order. This sovereign, whether a monarch or an assembly, becomes the *Leviathan*—an absolute authority that prevents the "war of all against all" Hobbes believed would otherwise exist.

Consider the practical implications of this theory. Hobbes’ social contract is not a voluntary agreement in the modern sense but a rational necessity. Imagine a society without laws or enforcement—a scenario not unlike post-apocalyptic fiction. In such chaos, Hobbes argues, individuals would logically consent to a powerful authority to escape constant fear and violence. This isn’t about democracy or equality; it’s about survival. For instance, in conflict zones where state authority collapses, Hobbes’ theory becomes eerily relevant as communities often seek strong leaders to restore order, even at the cost of individual liberties.

However, Hobbes’ theory is not without its pitfalls. Critics argue that his vision of the state of nature is overly pessimistic, and his solution—absolute sovereignty—risks tyranny. For example, authoritarian regimes often justify their power using Hobbesian logic, claiming that only their rule can prevent societal collapse. Yet, history shows that such regimes frequently exploit this authority, undermining the very security they promise. This tension highlights the need to balance order with individual rights, a challenge Hobbes’ theory doesn’t fully address.

To apply Hobbes’ ideas constructively, consider them as a cautionary tale rather than a blueprint. Modern societies can use his framework to evaluate the legitimacy of political power: Is the state fulfilling its end of the bargain by ensuring security and justice? For instance, during crises like pandemics or economic collapses, governments often invoke emergency powers. Hobbes would argue this is justified if it prevents chaos, but citizens must remain vigilant to ensure these measures are temporary and proportionate.

In conclusion, Hobbes’ social contract theory in *Leviathan* offers a stark but insightful perspective on the origins and purpose of political authority. While his vision of absolute sovereignty may seem extreme, it forces us to confront the trade-offs between freedom and security. By examining his ideas critically, we can better navigate the complexities of governance in an uncertain world.

PBS Politics Monday: Cancellation Confirmed or Just a Rumor?

You may want to see also

Sovereignty and Absolute Authority

Thomas Hobbes' *Leviathan* presents sovereignty as an absolute, indivisible authority necessary for societal stability. This authority, embodied in a commonwealth, holds supreme power over all individuals within its jurisdiction. Hobbes argues that without such absolute sovereignty, humanity would revert to a "state of nature," characterized by perpetual fear and violence. This perspective is not merely theoretical; it reflects Hobbes' lived experience of the English Civil War, where the absence of centralized authority led to chaos. Sovereignty, in this context, is not a suggestion but a necessity, a bulwark against the inherent fragility of human coexistence.

To understand absolute authority, consider it as a contract—a voluntary surrender of individual freedoms in exchange for security. Hobbes likens this to a "social contract," where citizens agree to submit to a sovereign power to escape the "war of all against all." This authority is not arbitrary; it is justified by its ability to enforce laws, protect lives, and maintain order. For instance, modern nation-states exemplify this principle, where citizens cede certain liberties to governments in exchange for protection, infrastructure, and justice. However, the challenge lies in ensuring that this authority remains legitimate and does not degenerate into tyranny.

A critical aspect of absolute authority is its indivisibility. Hobbes insists that sovereignty cannot be shared or divided without risking instability. Shared power, he argues, leads to conflict, as seen in systems where multiple entities claim authority. For example, the power struggles between the monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy in 17th-century England illustrate the dangers of divided sovereignty. Hobbes’ solution is clear: a single, undisputed authority is essential to prevent societal collapse. This principle remains relevant in contemporary debates about federalism, where the balance between centralized and decentralized power is often contentious.

However, absolute authority is not without its pitfalls. While it promises stability, it also risks becoming oppressive if unchecked. Hobbes acknowledges this but argues that the alternative—anarchy—is far worse. Practical safeguards, such as constitutional limits and democratic accountability, have been developed in modern political systems to mitigate these risks. For instance, the U.S. Constitution divides power among branches of government to prevent any single entity from becoming tyrannical. This blend of Hobbesian principles with checks and balances demonstrates how absolute authority can be adapted to serve justice without sacrificing order.

In conclusion, sovereignty and absolute authority, as outlined in *Leviathan*, remain foundational concepts in political theory. They offer a framework for understanding the trade-offs between individual freedom and collective security. While Hobbes’ vision may seem extreme, its core insights—the need for centralized authority and the dangers of power vacuums—continue to shape governance. By studying these principles, we gain tools to navigate the complexities of modern politics, ensuring that authority serves its purpose without becoming a tool of oppression.

Understanding Political Behavior: Key Factors Shaping Public Engagement and Decisions

You may want to see also

Individual Rights vs. State Power

The tension between individual rights and state power is a cornerstone of political philosophy, and Thomas Hobbes’ *Leviathan* offers a stark exploration of this dynamic. Hobbes argues that individuals must surrender their natural freedoms to a sovereign authority to escape the “war of all against all” in the state of nature. This trade—personal liberty for collective security—frames the debate: How much power should the state wield, and at what cost to individual autonomy? Hobbes’ answer is absolute sovereignty, but this raises critical questions about the limits of state authority and the protection of personal rights.

Consider the practical implications of this balance in modern governance. In democratic societies, constitutions often act as safeguards, delineating the boundaries of state power while guaranteeing individual rights. For instance, the U.S. Bill of Rights explicitly protects freedoms like speech, religion, and due process, even as the government exercises authority over taxation, defense, and law enforcement. Yet, these boundaries are not static. Emergencies, such as pandemics or wars, often test this equilibrium, as states may temporarily expand their powers—think lockdowns, surveillance, or conscription—raising concerns about overreach and the erosion of liberties.

A comparative lens reveals how different political systems navigate this tension. Authoritarian regimes prioritize state power, often suppressing individual rights in the name of stability or ideology. China’s social credit system, for example, exemplifies state control over personal behavior, while liberal democracies like Sweden emphasize individual freedoms within a framework of collective welfare. The key takeaway is that the balance is not binary but exists on a spectrum, shaped by cultural, historical, and institutional contexts.

To strike a sustainable balance, individuals must remain vigilant and engaged. Practical steps include advocating for transparency in governance, supporting independent judiciaries, and participating in civic education to understand rights and responsibilities. Caution is warranted against complacency, as unchecked state power can lead to tyranny, while unbridled individualism risks social fragmentation. Ultimately, the ideal relationship between individual rights and state power is not fixed but requires continuous negotiation, reflecting the evolving needs and values of society.

Measuring Political Equality: Tools, Challenges, and Pathways to Fair Representation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fear and Human Nature’s Role

Fear is the invisible thread that weaves through the fabric of political systems, and Thomas Hobbes’ *Leviathan* exemplifies this by positing that fear of chaos and death drives humans to surrender their freedoms to a sovereign authority. This primal fear, rooted in human nature, is not merely a reaction to external threats but a psychological constant that shapes collective behavior. Hobbes argues that without a central power to instill order, individuals would revert to a “war of all against all,” driven by self-preservation and competition. This fear-driven calculus—security over liberty—forms the bedrock of his political theory, revealing how deeply human nature is intertwined with the need for stability.

Consider the practical application of this fear in modern governance. During crises, such as pandemics or economic collapses, governments often leverage fear to justify expanded powers. For instance, lockdowns and surveillance measures during COVID-19 were framed as necessary to prevent catastrophic loss of life, echoing Hobbes’ argument that individuals implicitly consent to authority when faced with existential threats. However, this dynamic raises ethical questions: at what point does fear become a tool for control rather than a safeguard? The dosage of fear in political messaging must be carefully calibrated—too little risks complacency, while too much breeds authoritarianism.

To navigate this tension, individuals and societies must cultivate critical awareness of fear’s role in politics. A three-step approach can help: first, recognize fear-based narratives in political discourse by identifying alarmist language or exaggerated threats. Second, evaluate the proportionality of proposed solutions to the actual risks, ensuring they do not infringe disproportionately on rights. Third, foster collective resilience through education and dialogue, reducing the susceptibility to fear-driven manipulation. For example, age-specific programs in schools can teach younger generations to analyze political messaging critically, while community forums can provide platforms for informed debate.

Comparatively, while Hobbes sees fear as a unifying force, other philosophers, like John Locke, argue that human nature inclines toward reason and cooperation, making fear a less dominant political motivator. This contrast highlights the importance of context: fear’s role in politics is not universal but contingent on societal conditions. In stable democracies, fear may play a minimal role, whereas in fragile states, it becomes a central organizing principle. Understanding this variability allows for tailored responses, such as strengthening institutions in unstable regions to reduce reliance on fear-based governance.

Ultimately, fear’s role in human nature is both a vulnerability and a survival mechanism. Hobbes’ *Leviathan* serves as a cautionary tale about the trade-offs between security and freedom, reminding us that fear, when unchecked, can erode the very liberties it seeks to protect. By acknowledging fear’s dual nature and implementing practical strategies to mitigate its misuse, societies can harness its protective aspects without succumbing to its pitfalls. This delicate balance is the key to ensuring that fear remains a servant of human nature, not its master.

Mastering the Art of Gracious Silence: How to Politely Decline Answers

You may want to see also

Leviathan’s Influence on Modern Politics

Thomas Hobbes' *Leviathan*, published in 1651, remains a cornerstone of political philosophy, but its influence on modern politics is often misunderstood. At its core, the *Leviathan* argues for a strong central authority—a "commonwealth"—to prevent the chaos of the "state of nature." This idea resonates in contemporary debates about the role of government, particularly in balancing individual freedoms with collective security. Modern states, from liberal democracies to authoritarian regimes, grapple with this tension, often citing Hobbesian principles to justify their actions. For instance, surveillance programs and emergency powers are frequently defended as necessary to protect citizens from internal and external threats, echoing Hobbes' argument for absolute sovereignty.

Consider the post-9/11 era, where governments worldwide expanded their security apparatuses under the guise of safeguarding national interests. The USA PATRIOT Act in the United States, for example, granted unprecedented powers to law enforcement agencies, mirroring Hobbes' belief in a centralized authority to maintain order. Critics argue that such measures erode civil liberties, but proponents counter that they are essential to prevent societal collapse—a Hobbesian nightmare. This dynamic illustrates how the *Leviathan’s* logic continues to shape policy, even in democracies that ostensibly reject absolute rule.

However, the *Leviathan’s* influence is not limited to security policies. Its emphasis on social contracts and the legitimacy of governance also informs modern political discourse. In democratic societies, elections serve as a mechanism to establish consent, aligning with Hobbes' idea that authority derives from the collective will of the people. Yet, the rise of populist movements challenges this framework, as leaders often claim direct mandates to bypass institutional checks, echoing Hobbes' skepticism of intermediary bodies. This tension highlights the *Leviathan’s* enduring relevance in debates about the nature and limits of political power.

To apply Hobbes' ideas practically, policymakers must navigate a delicate balance. For instance, when implementing public health measures during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, governments must weigh the need for centralized control against the risk of overreach. A Hobbesian approach would prioritize decisive action to prevent chaos, but modern societies demand transparency and accountability. Here, the *Leviathan* serves as a cautionary tale: unchecked authority, even in the name of order, can lead to tyranny. Thus, while its principles remain influential, they must be adapted to fit the complexities of contemporary governance.

Ultimately, the *Leviathan’s* influence on modern politics lies in its ability to provoke critical questions about the role of the state. How much power should governments wield? What constitutes legitimate authority? These questions are as relevant today as they were in Hobbes' time. By examining the *Leviathan* through a modern lens, we gain insights into the challenges of building stable, just societies. Its legacy is not a blueprint for governance but a framework for understanding the perennial struggle between order and freedom.

Understanding Political Maps: Boundaries, Governments, and Electoral Insights Revealed

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the Leviathan, as described by Thomas Hobbes in his 1651 work *Leviathan*, represents a political entity—a sovereign state or commonwealth created through a social contract to maintain order and prevent the "war of all against all" in the state of nature.

The Leviathan serves to establish and enforce laws, protect individuals from chaos, and ensure peace and security. Its primary purpose is to act as an absolute authority to prevent societal collapse.

Hobbes argues that the Leviathan’s authority is political, derived from the consent of individuals who agree to form a commonwealth. While Hobbes acknowledges the existence of God, the Leviathan’s power is secular and based on human agreement.

The Leviathan’s concept of a centralized, absolute authority influenced modern political theories, particularly those emphasizing strong central governments. It laid the groundwork for ideas about sovereignty and the social contract in political philosophy.

Hobbes presents the Leviathan as a necessity rather than an ideal. He argues that without such a powerful authority, humanity would revert to a state of constant conflict, making the Leviathan essential for survival and stability.