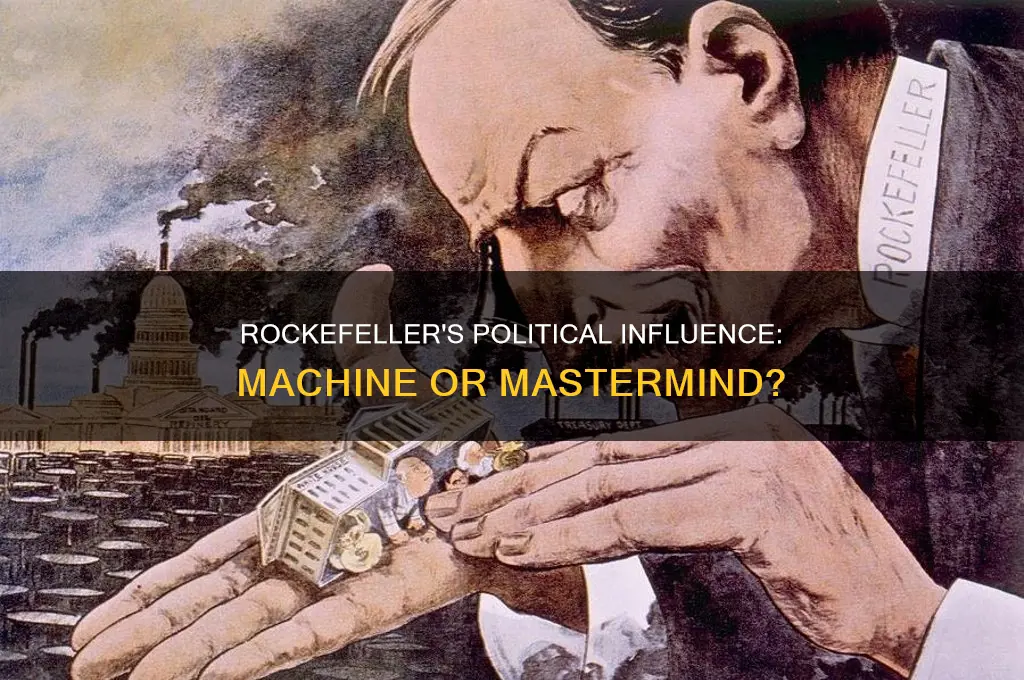

John D. Rockefeller, the industrialist and founder of Standard Oil, is often discussed in relation to political influence rather than being a political machine in the traditional sense. While Rockefeller’s immense wealth and business acumen granted him significant sway over political and economic landscapes, particularly during the Gilded Age, he did not operate a formal political machine like those associated with urban bosses such as Boss Tweed. Instead, Rockefeller’s influence was more indirect, leveraging his financial resources, lobbying efforts, and strategic alliances to shape policies favorable to his interests. His ability to manipulate markets, influence legislation, and cultivate relationships with politicians underscores his role as a powerful figure in American politics, but his methods were more aligned with corporate power than the organizational structure of a traditional political machine.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Influence | Rockefeller, particularly John D. Rockefeller and later Nelson Rockefeller, wielded significant political influence through wealth, philanthropy, and strategic alliances. |

| Party Affiliation | Strongly associated with the Republican Party, especially during the Gilded Age and early 20th century. |

| Patronage System | Utilized financial resources to support political candidates and gain loyalty, similar to a political machine. |

| Control Over Institutions | Influenced political, economic, and social institutions through the Rockefeller Foundation and other philanthropic efforts. |

| Policy Shaping | Played a key role in shaping policies, particularly in areas like healthcare, education, and international relations. |

| Network Building | Built extensive networks of allies, including politicians, business leaders, and civic organizations. |

| Public Perception | Often viewed as a powerful figure with machine-like control, though not a traditional political machine boss. |

| Legacy in Politics | Nelson Rockefeller served as Vice President and Governor of New York, further cementing the family's political legacy. |

| Criticism | Faced criticism for using wealth to manipulate political outcomes and consolidate power. |

| Distinction from Machines | Lacked the localized, ward-based structure typical of traditional political machines like Tammany Hall. |

Explore related products

$20.98 $39

What You'll Learn

Rockefeller's Influence on GOP Politics

The Rockefeller family's influence on the Republican Party (GOP) is a study in the power of wealth, ideology, and strategic political engagement. Nelson Rockefeller, in particular, embodied the liberal wing of the GOP during the mid-20th century, advocating for progressive policies like civil rights, environmental protection, and social welfare programs. His leadership as Governor of New York and his repeated bids for the presidency reshaped the party’s internal dynamics, often pitting him against conservative factions led by figures like Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan. This ideological divide highlights how the Rockefellers’ influence was both transformative and contentious within the GOP.

To understand their impact, consider the mechanics of political influence: financial contributions, policy advocacy, and institutional control. The Rockefellers leveraged their vast wealth to fund campaigns, think tanks, and political organizations that promoted moderate Republicanism. For instance, Nelson Rockefeller’s 1960s-era Commission on Critical Choices for Americans laid out a blueprint for centrist policies, influencing GOP platforms for decades. However, their approach was not without backlash. Critics within the party accused them of diluting conservative principles, setting the stage for the eventual rise of the New Right in the 1980s.

A comparative analysis reveals the Rockefellers’ unique role in GOP politics. Unlike other political dynasties, such as the Bush family, the Rockefellers were less about building a political legacy through elected office and more about shaping the party’s ideological direction. Their influence was institutional rather than personal, focusing on policy frameworks and organizational structures. This distinction explains why their impact persists in debates over the GOP’s identity, even as the party has shifted further to the right in recent decades.

Practical takeaways from the Rockefellers’ influence include the importance of long-term strategic planning in politics. Their ability to sustain influence over generations underscores the value of investing in ideas and institutions, not just individual candidates. For modern political operatives, this suggests that building think tanks, policy networks, and grassroots organizations can be as critical as campaign financing. However, it also cautions against alienating core party constituencies, as the Rockefellers’ liberal stances eventually marginalized them within the GOP.

In conclusion, the Rockefellers’ influence on GOP politics was a double-edged sword. While they expanded the party’s appeal to moderate voters and advanced progressive policies, their efforts also deepened internal divisions. Their legacy serves as a reminder that political influence is not just about power but about navigating the complexities of ideology, strategy, and coalition-building. For those seeking to shape a party’s direction, the Rockefeller example offers both inspiration and cautionary lessons.

Are Political Texts Legal? Understanding Campaign Messaging Rules and Regulations

You may want to see also

Campaign Funding and Political Control

John D. Rockefeller's influence on American politics extended far beyond his business empire, raising questions about the role of campaign funding in shaping political control. A key example is his strategic financial support during the Progressive Era, where he backed candidates and causes that aligned with his interests, such as tariff protection for the oil industry. This practice highlights how targeted funding can sway political agendas, creating a symbiotic relationship between wealth and power. Rockefeller's approach was not merely about donating money but about investing in outcomes that would safeguard his economic dominance.

To understand the mechanics of this control, consider the following steps: first, identify key political races or issues that impact your industry. Second, allocate funds to candidates or organizations that advocate for favorable policies. Third, maintain ongoing relationships with these political actors to ensure continued alignment. Rockefeller's success in this area demonstrates the importance of long-term strategic planning in campaign funding. However, caution must be exercised to avoid legal pitfalls, such as violating campaign finance laws or appearing to "buy" political favor, which can lead to public backlash.

A comparative analysis reveals that Rockefeller's methods were not unique but were executed with unparalleled precision. Unlike other industrialists of his time, he combined financial resources with a deep understanding of political dynamics, often working behind the scenes to avoid direct scrutiny. For instance, while Andrew Carnegie focused on philanthropy as a means of social control, Rockefeller used campaign funding as a tool for political influence. This distinction underscores the versatility of wealth in shaping public and private spheres.

Persuasively, one could argue that Rockefeller's model of campaign funding set a precedent for modern political financing. His ability to funnel money into specific races and causes laid the groundwork for today's Super PACs and dark money groups. While the scale and methods have evolved, the core principle remains: financial contributions can disproportionately influence policy-making. This raises ethical questions about the fairness of a system where wealth often translates to political control, marginalizing the voices of less affluent citizens.

Practically, individuals and organizations seeking to navigate campaign funding should adhere to these tips: first, research candidates' track records to ensure alignment with your goals. Second, diversify funding across multiple races or issues to maximize impact. Third, leverage transparency where possible to build public trust. Rockefeller's legacy serves as both a blueprint and a cautionary tale, illustrating the power and peril of using financial resources to shape political landscapes. By studying his strategies, one can gain insights into the enduring interplay between money and politics.

Understanding Political Activism: Engaging in Democracy and Driving Change

You may want to see also

Standard Oil's Political Leverage

Consider the tactics employed: Standard Oil often funded political campaigns of both major parties, ensuring bipartisan support for its interests. For instance, the company’s donations to Republican and Democratic candidates alike guaranteed that, regardless of election outcomes, its agenda remained intact. Additionally, Rockefeller’s team cultivated relationships with key lawmakers, offering financial incentives in exchange for legislative favors. One notable example was the company’s ability to delay or weaken early antitrust bills, such as the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which was initially toothless due to political maneuvering. These actions demonstrate how Standard Oil’s wealth became a tool for political manipulation, blurring the lines between corporate and governmental power.

To replicate such leverage in a modern context, one might analyze Standard Oil’s playbook as a blueprint for corporate political engagement. Step one: identify key policymakers and their vulnerabilities, whether financial needs or career ambitions. Step two: deploy resources strategically, such as campaign donations or targeted lobbying efforts, to align their interests with your own. Step three: maintain a low profile to avoid public backlash, as Rockefeller often did by operating behind the scenes. Caution: overreach can lead to public scrutiny and regulatory backlash, as Standard Oil eventually faced with the breakup of its monopoly in 1911. The takeaway is that political leverage requires precision, subtlety, and a long-term strategy.

Comparatively, Standard Oil’s approach contrasts with modern corporate lobbying, which often relies on more transparent methods like PACs (Political Action Committees) and public advocacy campaigns. Rockefeller’s era lacked today’s regulatory frameworks and media scrutiny, allowing for more covert operations. However, the core principle remains: economic power can be converted into political influence. For instance, while Standard Oil used direct bribes and backroom deals, contemporary corporations employ sophisticated lobbying firms and think tanks to shape policy narratives. The difference lies in the methods, not the intent. Both eras highlight the symbiotic relationship between wealth and political control.

Descriptively, Standard Oil’s political machine was a well-oiled apparatus, pun intended. Rockefeller’s team meticulously mapped out legislative landscapes, identifying allies and opponents. They employed a network of agents to monitor political developments and intervene when necessary. For example, when state legislatures threatened to regulate oil prices, Standard Oil would flood local markets with cheap oil, undercutting competitors and forcing compliance. This combination of economic coercion and political persuasion created an environment where resistance was futile. The company’s ability to dictate terms to elected officials underscores the extent of its leverage, painting a vivid picture of corporate power at its zenith.

Cuba's Political Prisoners: Uncovering the Hidden Numbers and Realities

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Relationships with State Legislatures

John D. Rockefeller's relationship with state legislatures was a masterclass in strategic influence, blending financial leverage, personal networks, and policy alignment to shape legislative outcomes. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company often targeted statehouses to secure favorable regulations, tax structures, and operational freedoms. For instance, in Ohio, his home state, Rockefeller cultivated relationships with key legislators, offering campaign contributions and business incentives in exchange for laws that protected Standard Oil’s monopoly. This quid pro quo dynamic was replicated in Pennsylvania and New York, where his company’s dominance in the oil refining industry was cemented through legislative cooperation. By controlling the legislative environment, Rockefeller ensured that state governments became de facto partners in his corporate empire, rather than regulators.

To replicate Rockefeller’s approach in modern contexts, focus on building relationships with legislators through consistent engagement, not just transactional exchanges. Start by identifying key committees and lawmakers overseeing industries relevant to your interests. For example, if you’re in the energy sector, target state energy or commerce committees. Offer expertise through testimony or white papers that align your goals with public policy objectives, such as job creation or economic growth. Rockefeller’s success hinged on making legislators see his interests as synonymous with state prosperity. Emulate this by framing your advocacy as mutually beneficial, not self-serving.

A cautionary note: Rockefeller’s tactics often blurred ethical lines, leading to public backlash and eventual antitrust scrutiny. Modern efforts to influence state legislatures must navigate stricter transparency laws and heightened public scrutiny. Avoid direct quid pro quo arrangements, which can be legally and reputationally risky. Instead, focus on long-term relationship-building and policy education. For instance, host informational sessions for legislators or sponsor non-partisan research on industry trends. Rockefeller’s legacy underscores the importance of balancing influence with accountability to avoid becoming a target of regulatory or public ire.

Comparatively, Rockefeller’s state-level strategies differed from his federal lobbying efforts, which were less successful due to the broader political landscape. At the state level, he could concentrate resources and personal attention on a smaller number of decision-makers, whereas federal politics required navigating a more complex web of interests. This localized focus allowed him to dominate state legislatures in ways that were harder to replicate nationally. For businesses or advocates today, this highlights the value of prioritizing state-level engagement, especially in industries heavily regulated at the state level, such as healthcare or energy.

In practical terms, Rockefeller’s approach can be distilled into three actionable steps: first, map the legislative landscape to identify allies and potential opponents. Second, invest in relationship-building through regular communication, campaign support, and shared policy initiatives. Third, align your interests with broader state goals, such as economic development or environmental sustainability. For example, if you’re in the tech industry, propose legislation that fosters innovation while addressing workforce training needs. By following these steps, you can emulate Rockefeller’s success in leveraging state legislatures without repeating his ethical missteps.

Is a PSA Political? Analyzing Public Service Announcements' Role in Society

You may want to see also

Impact on Progressive Era Reforms

John D. Rockefeller's influence during the Progressive Era was both profound and paradoxical. While he was not a traditional political machine boss, his vast wealth and strategic philanthropy shaped the reform landscape in ways that both advanced and complicated progressive ideals. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil fortune funded institutions like the University of Chicago and the General Education Board, which became incubators for progressive thought and policy. These institutions pushed for education reform, public health initiatives, and efficiency in government—hallmarks of the Progressive Era. Yet, his business practices, which often stifled competition and exploited workers, stood in stark contrast to the era’s calls for fairness and regulation. This duality underscores how Rockefeller’s impact was less about direct political control and more about systemic influence, leaving a legacy that both propelled and challenged progressive reforms.

Consider the role of Rockefeller’s philanthropy in public health, a key progressive concern. The Rockefeller Foundation, established in 1913, spearheaded campaigns against hookworm and yellow fever, improving health outcomes for millions. For instance, in the American South, the Foundation’s hookworm eradication program reduced infection rates from 40% to less than 1% in targeted areas by 1920. This was achieved through a combination of medical treatment, sanitation improvements, and public education. However, critics argue that such initiatives often prioritized efficiency over local autonomy, reflecting Rockefeller’s business-minded approach to reform. While these efforts undeniably advanced public welfare, they also highlighted the tension between top-down solutions and grassroots progressive ideals.

Rockefeller’s influence on education reform offers another lens into his impact. The General Education Board, funded by his donations, aimed to modernize American schools, particularly in rural areas. Between 1902 and 1934, the Board distributed over $100 million to improve teacher training, curriculum standards, and school infrastructure. This investment helped lay the groundwork for the modern education system. Yet, it also reflected Rockefeller’s belief in education as a tool for social control, emphasizing vocational training and conformity over critical thinking. This approach aligned with some progressive goals but clashed with others, such as John Dewey’s vision of education as a means of fostering democratic citizenship.

To understand Rockefeller’s legacy, it’s instructive to compare his methods with those of traditional political machines. Unlike bosses like Tammany Hall’s William Tweed, Rockefeller did not rely on patronage or electoral manipulation. Instead, he wielded power through institutions and ideas, shaping policy indirectly. For example, his support for the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913 reflected his interest in stabilizing the economy, a goal shared by many progressives. However, his opposition to antitrust regulation, even as Standard Oil faced scrutiny, revealed a disconnect between his business interests and progressive demands for corporate accountability. This contrast illustrates how Rockefeller’s influence was both a driving force and a barrier to reform.

In practical terms, Rockefeller’s impact on Progressive Era reforms serves as a cautionary tale for modern philanthropists and policymakers. While his investments in public health and education yielded tangible benefits, they also demonstrated the risks of unchecked private influence in public affairs. For those seeking to drive systemic change today, the lesson is clear: align financial power with democratic values, prioritize local input, and remain vigilant against the concentration of influence. Rockefeller’s legacy reminds us that even well-intentioned efforts can perpetuate inequalities if they fail to address the root causes of injustice. By studying his role in the Progressive Era, we gain insights into how to balance ambition with accountability in the pursuit of reform.

Understanding Global Political Brinkmanship: Risks, Strategies, and Consequences

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

John D. Rockefeller, the oil magnate and philanthropist, was not directly involved in running a political machine. However, his wealth and influence allowed him to wield significant power in politics, often supporting Republican candidates and policies.

Rockefeller did not control political machines in the traditional sense, but his financial contributions and connections gave him considerable sway over political outcomes, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

While Rockefeller's influence was immense, it was more individual and corporate in nature rather than part of a structured political machine. Political machines typically involve organized networks of patronage and control, which Rockefeller did not directly operate.