The question of whether we should maintain the system of political parties is a contentious and thought-provoking issue in modern politics. Political parties have long been a cornerstone of democratic governance, providing a framework for organizing political ideologies, mobilizing voters, and facilitating representation. However, critics argue that they often prioritize partisan interests over the common good, foster polarization, and hinder effective governance. Proponents, on the other hand, contend that parties are essential for aggregating diverse interests, simplifying electoral choices, and ensuring accountability. As societies grapple with increasing political fragmentation and disillusionment, reevaluating the role and relevance of political parties becomes imperative to address systemic challenges and strengthen democratic institutions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Representation | Political parties aggregate and represent diverse interests, providing a voice for various groups in society. |

| Mobilization | They mobilize citizens, encourage political participation, and increase voter turnout. |

| Policy Formulation | Parties develop and promote policies, offering clear choices to voters and facilitating governance. |

| Stability | In democratic systems, parties can provide stability by forming governments and managing coalitions. |

| Accountability | They hold governments accountable by acting as opposition and scrutinizing policies. |

| Fragmentation | Can lead to polarization and gridlock, especially in multi-party systems. |

| Corruption | Parties may engage in corrupt practices, such as lobbying for special interests or misusing funds. |

| Elitism | Often dominated by elites, potentially marginalizing grassroots voices. |

| Ideological Rigidity | Parties may prioritize ideology over pragmatism, hindering compromise. |

| Alternatives | Non-partisan systems or direct democracy are proposed as alternatives, though they have their own challenges. |

| Public Opinion | Surveys show mixed views; some support parties for structure, while others criticize them for division. |

| Global Trends | Many democracies retain parties, but there’s a rise in anti-establishment movements and independent candidates. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Pros of Multi-Party Systems: Encourages diverse representation, fosters competition, and promotes accountability through opposition

- Cons of Party Politics: Risks polarization, fosters corruption, and prioritizes party interests over public good

- Alternatives to Parties: Direct democracy, technocracy, or issue-based governance as potential replacements

- Historical Impact of Parties: Role in shaping nations, revolutions, and societal progress or decline

- Reforming Party Systems: Measures like funding transparency, term limits, and anti-polarization policies

Pros of Multi-Party Systems: Encourages diverse representation, fosters competition, and promotes accountability through opposition

Multi-party systems inherently amplify diverse representation by creating space for a wide array of ideologies, identities, and interests. Unlike two-party systems, which often force issues into binary choices, multi-party frameworks allow smaller parties to advocate for niche concerns—whether environmental sustainability, regional autonomy, or minority rights. For instance, Germany’s Bundestag includes parties like the Greens and the Left, ensuring that ecological and socialist perspectives are not marginalized. This diversity mirrors the complexity of society, giving voice to groups that might otherwise be overlooked, and fostering policies that reflect a broader spectrum of public opinion.

Competition is the lifeblood of multi-party systems, driving parties to innovate, adapt, and perform. With multiple contenders vying for power, there’s a constant pressure to deliver on campaign promises, refine platforms, and engage voters effectively. Consider India’s vibrant political landscape, where regional parties like the Aam Aadmi Party challenge established giants like the BJP and Congress, pushing all players to address local issues and improve governance. This competitive dynamic prevents complacency and ensures that parties remain responsive to citizen needs, as failure to do so risks losing ground to rivals.

Opposition in multi-party systems serves as a critical check on power, holding ruling parties accountable for their actions. When no single party dominates, coalitions often form, and opposition blocs scrutinize government decisions, expose corruption, and propose alternatives. In countries like Sweden, where coalition governments are common, opposition parties play a vital role in shaping policy debates and preventing unilateral decision-making. This accountability mechanism reduces the risk of authoritarian tendencies and ensures that power remains decentralized and balanced.

However, realizing these benefits requires careful institutional design. Proportional representation systems, for example, are more effective at translating diverse votes into parliamentary seats than winner-take-all models. Additionally, robust civil society and free media are essential to amplify opposition voices and keep voters informed. Without these safeguards, multi-party systems can devolve into fragmentation or gridlock. Yet, when structured thoughtfully, they offer a dynamic framework for representation, competition, and accountability that single or two-party systems struggle to match.

Why Political Parties Dealign: Causes, Consequences, and Shifting Voter Loyalties

You may want to see also

Cons of Party Politics: Risks polarization, fosters corruption, and prioritizes party interests over public good

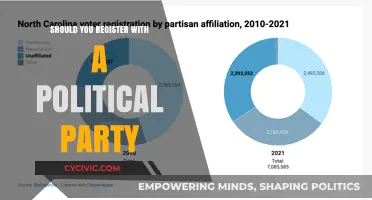

Political parties, by their very nature, often exacerbate societal divisions. Consider the United States, where the two-party system has deepened ideological rifts, turning policy debates into zero-sum battles. A 2021 Pew Research Center study found that 90% of Americans believe there is more ideological difference between Democrats and Republicans than in the past, with 59% viewing these differences as a "very big problem." This polarization isn’t unique to the U.S.; countries like India and Brazil have seen similar trends, where party loyalties overshadow shared national goals. The takeaway? Parties can amplify differences, making compromise nearly impossible and governance increasingly dysfunctional.

Corruption thrives in environments where power is concentrated, and political parties often serve as vehicles for such concentration. In Nigeria, for instance, party politics has been linked to systemic corruption, with resources diverted to fund campaigns and reward loyalists rather than serve public needs. A 2020 Transparency International report ranked Nigeria 149th out of 180 countries on its Corruption Perceptions Index, highlighting the corrosive effect of party-driven politics. This isn’t an isolated case; in Italy, the "Clean Hands" scandal of the 1990s exposed widespread corruption tied to party financing. The lesson here is clear: when parties prioritize survival over integrity, the public pays the price.

Parties inherently operate as interest groups, but their interests often diverge sharply from the public good. Take the European Union’s struggles with climate policy, where member states’ party politics have repeatedly delayed ambitious legislation. In Germany, the coalition government’s 2023 climate plan faced criticism for prioritizing industry interests over environmental goals, as parties sought to appease their voter bases. Similarly, in the U.S., pharmaceutical lobbying has influenced both major parties, resulting in drug prices that are 2.5 times higher than in other developed nations. The pattern is unmistakable: party interests can hijack policy-making, leaving citizens with suboptimal outcomes.

To mitigate these risks, consider a two-pronged approach. First, implement stricter campaign finance reforms to reduce parties’ reliance on special interests. For example, Canada’s 2004 Election Act capped corporate and union donations, forcing parties to engage more directly with individual voters. Second, encourage cross-party collaboration through mechanisms like New Zealand’s Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) system, which fosters coalition-building and reduces extreme partisanship. While these steps won’t eliminate the downsides of party politics, they can help rebalance the scales in favor of the public good. The challenge lies in implementation, but the alternative—a system where parties reign unchecked—is far costlier.

Unveiling the Power Dynamics of Historical Political Rings

You may want to see also

Alternatives to Parties: Direct democracy, technocracy, or issue-based governance as potential replacements

The debate over whether to retain political parties often leads to discussions about alternative systems that could address their perceived shortcomings. Among the most frequently proposed alternatives are direct democracy, technocracy, and issue-based governance. Each of these models offers a distinct approach to decision-making, but they also come with their own challenges and trade-offs. Understanding their mechanics and implications is crucial for evaluating whether they could serve as viable replacements for party-based systems.

Direct democracy, where citizens vote directly on policies rather than electing representatives, is often hailed as a way to bypass party politics and empower individuals. Switzerland, for instance, uses referendums extensively, allowing citizens to shape laws on issues ranging from immigration to healthcare. However, this system requires a highly engaged and informed electorate. In practice, low voter turnout or misinformation can skew outcomes. For direct democracy to work effectively, governments must invest in civic education and accessible information platforms. Without these, it risks becoming a tool for the most vocal or well-funded groups, undermining its egalitarian promise.

Technocracy, in contrast, shifts decision-making power to experts and specialists, prioritizing technical knowledge over political maneuvering. This model is particularly appealing in areas like climate policy or public health, where scientific consensus is critical. Estonia’s e-governance system, which relies on data-driven decision-making, is a partial example of technocratic principles in action. Yet, technocracy raises concerns about accountability and representation. Who determines which experts hold power, and how are their decisions challenged or reviewed? Without mechanisms for public oversight, technocracy could lead to elitism or disregard for social equity. Balancing expertise with democratic checks is essential for its success.

Issue-based governance, meanwhile, proposes organizing political activity around specific issues rather than party platforms. This approach could reduce polarization by allowing citizens to align with policies rather than ideologies. New Zealand’s cross-party collaboration on climate change legislation demonstrates how issue-based governance can foster consensus. However, this model struggles with scalability and coordination. Without overarching structures, it risks fragmenting political efforts and diluting accountability. Implementing issue-based governance would require robust frameworks for issue prioritization and conflict resolution, possibly involving hybrid systems that combine direct participation with representative elements.

Each of these alternatives offers a pathway to address the limitations of political parties, but none is without flaws. Direct democracy demands an informed and engaged citizenry, technocracy requires careful safeguards against elitism, and issue-based governance needs mechanisms to ensure coherence and accountability. Rather than viewing these models as complete replacements, they could be integrated into existing systems to enhance participation, expertise, and responsiveness. The key lies in adapting their strengths to address specific challenges, rather than adopting them wholesale.

Finding Your Political Home: Which Country Aligns with Your Beliefs?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.99 $30

Historical Impact of Parties: Role in shaping nations, revolutions, and societal progress or decline

Political parties have been the architects of nations, often serving as the backbone of revolutionary change. Consider the French Revolution, where factions like the Jacobins and Girondins not only accelerated the overthrow of the monarchy but also shaped the ideological contours of modern democracy. These parties were not mere bystanders; they were catalysts, mobilizing masses and drafting policies that redefined societal structures. Their influence extended beyond France, inspiring movements across Europe and beyond. Without such organized groups, the revolution might have lacked direction, resulting in fragmented outcomes rather than a coherent shift toward republican ideals.

However, the role of political parties in revolutions is a double-edged sword. In Russia, the Bolsheviks’ rise to power during the 1917 Revolution demonstrated how a single party could monopolize control, leading to decades of authoritarian rule. While they achieved rapid industrialization and societal transformation, the cost was immense: political repression, economic inefficiencies, and the stifling of dissent. This example underscores the danger of unchecked party dominance, where progress is often accompanied by decline in individual freedoms and pluralism.

Parties have also been instrumental in societal progress, particularly in advancing civil rights and social justice. The Democratic Party in the United States, for instance, played a pivotal role in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a landmark legislation that dismantled segregation and expanded voting rights. This achievement was the culmination of decades of grassroots organizing, legislative maneuvering, and coalition-building within the party. Such progress highlights the potential of parties to act as vehicles for positive change when they align with broader societal aspirations.

Conversely, the decline of societies has often been linked to the failures or excesses of political parties. In Weimar Germany, the fragmentation of parties and their inability to form stable coalitions created a vacuum that the Nazi Party exploited. This case illustrates how party politics, when dysfunctional, can pave the way for extremism and societal collapse. The lesson here is clear: the structure and behavior of parties are not neutral; they can either fortify or undermine the health of a nation.

To navigate the historical impact of parties, one must adopt a critical lens. Analyze their role in specific contexts: Did they foster unity or division? Did they prioritize long-term stability or short-term gains? For instance, study how India’s Congress Party post-independence balanced diverse interests to maintain national cohesion, or how South Africa’s ANC transitioned from a liberation movement to a governing party. Practical tip: When evaluating whether to keep political parties, assess their adaptability—can they evolve to address contemporary challenges without repeating historical pitfalls? The answer lies not in their abolition but in their reform and responsible stewardship.

Unveiling the Author Behind 'Political Behaviour': A Comprehensive Exploration

You may want to see also

Reforming Party Systems: Measures like funding transparency, term limits, and anti-polarization policies

Political parties, while essential for organizing democratic systems, often become entrenched in practices that undermine their effectiveness. Reforming party systems through measures like funding transparency, term limits, and anti-polarization policies can restore public trust and foster healthier political discourse. These reforms address systemic issues that contribute to corruption, stagnation, and ideological extremism, offering a pathway to more accountable and representative governance.

Funding Transparency: The Foundation of Accountability

Opaque financial flows between donors, parties, and candidates breed corruption and erode public trust. Implementing real-time disclosure requirements for campaign contributions and expenditures, coupled with accessible digital platforms, can demystify funding sources. For instance, countries like Canada and the UK mandate immediate reporting of donations over specific thresholds (e.g., £7,500 in the UK). Pairing transparency with caps on individual donations—say, $2,500 per donor per election cycle—limits undue influence. Caution: Avoid overly restrictive caps that push funding underground; instead, focus on traceability and public scrutiny. Takeaway: Transparent funding mechanisms ensure parties serve citizens, not special interests.

Term Limits: Breaking the Cycle of Entrenchment

Longevity in office often prioritizes reelection over policy innovation. Instituting term limits—for example, two consecutive terms for legislators—can rejuvenate political institutions by encouraging fresh perspectives. Mexico’s Senate limits members to one six-year term, fostering turnover. However, term limits must be balanced with experience retention; consider exempting committee chairs or allowing non-consecutive terms. Practical tip: Phase in limits gradually to avoid institutional knowledge loss. Analysis: While critics argue limits reduce expertise, they also curb the concentration of power and incentivize long-term policy thinking.

Anti-Polarization Policies: Bridging the Ideological Divide

Hyper-partisanship paralyzes governance and alienates voters. Ranked-choice voting (RCV), used in Australia and Maine, encourages candidates to appeal beyond their base by seeking second-choice votes. Another strategy is open primaries, where voters select candidates regardless of party affiliation, as seen in California’s "top-two" system. Comparative insight: Mixed-member proportional representation, as in Germany, blends local and party-list voting, reducing winner-takes-all dynamics. Caution: Anti-polarization measures must avoid diluting party identities entirely, as some ideological clarity is necessary for voter orientation. Conclusion: These policies foster collaboration without sacrificing diversity of thought.

Synergy of Reforms: A Holistic Approach

Isolating reforms risks incomplete solutions. Funding transparency without term limits leaves entrenched elites to exploit resources, while anti-polarization policies falter if parties remain unaccountable. A holistic approach—combining transparent funding, term limits, and inclusive electoral systems—creates a self-reinforcing cycle of accountability and moderation. Example: New Zealand’s public funding model ties party financing to electoral performance, incentivizing broad appeal. Practical tip: Pilot reforms regionally before national rollout to identify unintended consequences. Takeaway: Integrated reforms transform parties into adaptive, citizen-centric institutions.

By addressing funding, tenure, and polarization, these measures recalibrate party systems to prioritize public good over partisan gain. The challenge lies in implementation—requiring political will, citizen engagement, and iterative refinement. Yet, the payoff is clear: a democracy where parties are tools for representation, not barriers to it.

Political Party Perspectives: Understanding Their Core Beliefs and Policies

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political parties serve as essential structures for organizing political participation, aggregating interests, and simplifying voter choices. They provide a framework for governance by uniting individuals with shared ideologies, enabling efficient decision-making, and ensuring representation of diverse viewpoints in democratic systems.

While political parties can highlight differences, they also channel conflicts into peaceful, democratic processes. They provide platforms for debate and compromise, fostering stability and preventing societal fragmentation by offering organized avenues for dissent and participation.

Direct democracy and independent candidates have limitations in large, complex societies. Political parties streamline governance by mobilizing resources, formulating policies, and ensuring accountability. Eliminating them could lead to inefficiency, lack of coordination, and difficulty in addressing broad societal needs.