The question of whether there is a time delay to change political parties is a nuanced one, varying significantly across different countries and their respective electoral systems. In some nations, individuals can switch party affiliations almost instantaneously, while others impose mandatory waiting periods or restrictions, particularly for elected officials or during specific electoral cycles. These delays often aim to prevent opportunistic party-switching, maintain political stability, or ensure alignment with campaign promises. Understanding such regulations is crucial for both politicians and voters, as they can influence legislative dynamics, party cohesion, and the overall integrity of democratic processes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time Delay to Change Political Parties | Varies by country and jurisdiction; no universal rule. |

| United States | No formal time delay; voters can change party affiliation at any time, though deadlines exist for primary voting eligibility. |

| United Kingdom | No time delay; voters can join or switch parties at any time. |

| Canada | No formal delay; party membership changes can occur anytime. |

| Australia | No time delay; voters can change party membership freely. |

| Germany | No formal delay; party membership changes are allowed at any time. |

| France | No time delay; voters can join or switch parties freely. |

| India | No formal delay; party membership changes can occur anytime. |

| Brazil | No time delay; voters can change party affiliation freely. |

| Japan | No formal delay; party membership changes are allowed at any time. |

| General Trend | Most democracies do not impose a time delay for changing political parties, though administrative processes may apply. |

| Exceptions | Some countries may have internal party rules or deadlines for specific elections, but these are not universal. |

Explore related products

$28.31 $42

$11.59 $18.99

What You'll Learn

Legal Requirements for Party Switching

In many democratic systems, the act of switching political parties by elected officials is governed by specific legal frameworks designed to maintain stability and prevent opportunistic behavior. These laws often include provisions that dictate when and how such changes can occur, ensuring that the process aligns with the integrity of the political system. For instance, some countries impose a "cooling-off period" during which an elected official must wait before formally changing party affiliations. This delay is intended to discourage hasty decisions that could undermine public trust or disrupt legislative processes.

Consider the case of the Philippines, where the Party-List System Act explicitly prohibits party-list representatives from switching parties during their term. This law underscores the importance of consistency in representing the interests of the sector or group they were elected to serve. In contrast, countries like the United Kingdom operate under a more flexible system, allowing Members of Parliament to change parties without legal restrictions, though such moves are often subject to public and media scrutiny. These differing approaches highlight the balance between individual political freedom and systemic stability.

For those contemplating a party switch, understanding the legal requirements is crucial. In jurisdictions with strict regulations, such as India, the Anti-Defection Law mandates that a legislator must obtain prior approval from the party leadership before switching. Failure to comply can result in disqualification from office. Conversely, in the United States, while there are no federal laws governing party switching, state-level regulations may apply, particularly for state legislators. This patchwork of rules necessitates careful research and consultation with legal experts to navigate the process effectively.

A persuasive argument can be made for the necessity of these legal safeguards. By imposing time delays or procedural hurdles, such laws deter politicians from making impulsive decisions driven by personal gain rather than principled conviction. For example, a mandatory waiting period allows constituents and colleagues to assess the sincerity of the switch, fostering transparency and accountability. However, critics argue that overly restrictive laws can stifle political evolution, trapping officials in parties that no longer align with their values or the needs of their constituents.

In practical terms, individuals considering a party switch should take several steps to ensure compliance with legal requirements. First, thoroughly review the relevant laws and regulations in their jurisdiction. Second, consult with legal advisors to understand the potential consequences, including the risk of disqualification or loss of privileges. Third, engage in open communication with both the current and prospective party leadership to mitigate backlash and ensure a smooth transition. Finally, prepare a clear and compelling rationale for the switch, emphasizing alignment with core principles rather than expediency. By approaching the process methodically, politicians can navigate the legal landscape while maintaining their credibility and effectiveness.

Understanding Racial Identity Politics: Power, Representation, and Social Justice

You may want to see also

Notice Periods in Political Affiliations

In the realm of political affiliations, notice periods serve as a mechanism to regulate transitions between parties, ensuring stability and integrity within political systems. These periods, often mandated by party bylaws or national legislation, dictate the timeframe during which a member must declare their intent to switch allegiances. For instance, in the United Kingdom, Members of Parliament (MPs) who wish to defect to another party are typically required to inform their party leadership in advance, although the exact duration of this notice period can vary. This practice aims to minimize disruptions and allow parties to prepare for potential shifts in their parliamentary composition.

From an analytical perspective, notice periods in political affiliations function as a double-edged sword. On one hand, they provide parties with a buffer to manage the logistical and strategic implications of a member’s departure, such as redistributing roles or recalibrating policy stances. On the other hand, they can stifle individual political expression, forcing members to remain affiliated with a party they no longer align with until the notice period expires. This tension highlights the need for a balanced approach, where notice periods are long enough to ensure procedural fairness but not so lengthy as to constrain political freedom.

For individuals considering a party change, understanding the notice period is crucial. Practical steps include reviewing party constitutions or national laws to identify specific requirements, such as written notifications or consultations with party leaders. In some cases, like in India, politicians must wait for a cooling-off period before formally joining a new party to avoid accusations of opportunistic defection. Ignoring these rules can lead to penalties, including disqualification from office, as seen in the anti-defection laws of several countries.

A comparative analysis reveals that notice periods vary widely across jurisdictions. In the United States, there are no formal notice periods for party switches at the federal level, allowing politicians like Senator Mitt Romney to change affiliations with relative ease. Contrastingly, countries like Germany impose stricter regulations, requiring members to adhere to party guidelines that often include mandatory waiting periods. These differences reflect broader cultural and political attitudes toward party loyalty and individual autonomy.

In conclusion, notice periods in political affiliations are a critical yet often overlooked aspect of party dynamics. They serve as a tool for maintaining organizational stability while potentially limiting personal political expression. For politicians and citizens alike, awareness of these periods is essential for navigating the complexities of party transitions. By striking a balance between procedural fairness and individual freedom, notice periods can contribute to healthier, more transparent political systems.

The Rise and Fall of Political Machines: Who Held the Power?

You may want to see also

Consequences of Immediate Party Changes

Immediate party changes can destabilize legislative coalitions, particularly in parliamentary systems where governments rely on majority support. If a member switches parties mid-session, it could tip the balance of power, forcing a snap election or leading to a minority government. For instance, in the UK’s 2019 Brexit debates, defections from the Conservative Party to the Liberal Democrats temporarily weakened the government’s ability to pass key legislation. Such volatility underscores the risk of allowing unrestricted party switches during critical legislative periods.

From a voter’s perspective, immediate party changes can erode trust in elected officials. Constituents often vote based on party platforms, and a sudden switch may feel like a betrayal of campaign promises. In Canada, for example, a 2021 study found that 62% of respondents believed MPs who changed parties mid-term should resign and run in a by-election. This sentiment highlights the ethical dilemma: does an elected official represent themselves, their party, or their constituents? Without a cooling-off period, such actions can deepen political cynicism.

Immediate party changes also create strategic incentives for political maneuvering. In the U.S., where party switching is less common but still occurs, it often happens during lame-duck sessions or when a politician is retiring. This timing minimizes electoral backlash but can still influence key votes. For instance, a senator switching parties to secure committee chairmanships or favorable legislation could undermine the integrity of the legislative process. Such tactics emphasize the need for safeguards to prevent opportunistic defections.

Finally, the absence of a time delay for party changes can amplify polarization. When politicians switch parties without consequence, it encourages alignment with extreme factions to gain power or influence. In India, where party hopping is rampant, this has led to fragmented state legislatures and unstable governments. A mandatory waiting period, such as the six-month cooling-off period proposed in some European countries, could reduce impulsive decisions and encourage cross-party collaboration rather than division.

Practical reforms could include requiring a by-election for any mid-term party switch, as practiced in some Australian states, or imposing a 90-day public consultation period before a change is finalized. Such measures would balance the need for political flexibility with accountability, ensuring that immediate party changes do not undermine democratic stability.

Navigating Political Differences: How Couples Can Stay United in Divided Times

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Voter Perception of Quick Switches

Voters often view quick party switches with skepticism, questioning the authenticity of a politician’s ideological shift. A sudden change in allegiance, particularly during election seasons, can appear opportunistic rather than principled. For instance, a U.S. senator switching parties weeks before a primary might be seen as a tactical move to secure reelection rather than a genuine realignment with new values. This perception erodes trust, as constituents may feel the politician prioritizes personal gain over public service. Such switches can backfire, leading to voter disillusionment and, in some cases, electoral defeat.

To mitigate negative perceptions, politicians should communicate transparently about their reasons for switching parties. A detailed public statement explaining the ideological evolution, coupled with a track record of consistent votes or advocacy, can help legitimize the change. For example, a politician who has publicly criticized their party’s stance on climate policy for years before switching might be viewed more favorably than one who changes without prior indication. Timing also matters; switches made well ahead of elections, rather than in their immediate run-up, are less likely to be dismissed as politically motivated.

Comparatively, voters in multiparty systems like Germany or India may be more forgiving of party switches due to the fluidity of coalitions and ideological overlaps. In contrast, the U.S.’s two-party system amplifies the perceived drama of such moves, as they often involve crossing a stark ideological divide. This cultural context shapes voter expectations, with Americans tending to view party identity as more fixed. Politicians in such systems must work harder to reframe their switch as a principled stand rather than a pragmatic maneuver.

Practical advice for politicians considering a switch includes conducting a “listening tour” with constituents to gauge sentiment and build goodwill. Additionally, aligning the switch with a specific legislative issue or event can provide a narrative anchor. For instance, a politician switching parties to support a bipartisan infrastructure bill might be seen as putting country over party. Finally, avoiding overly defensive language in public statements can prevent the switch from appearing reactive or insincere.

In conclusion, while quick party switches are often met with voter suspicion, strategic communication and timing can soften the blow. Politicians must balance the need for self-preservation with the obligation to maintain public trust, ensuring their actions reflect genuine conviction rather than political expediency. Voters, in turn, should scrutinize both the timing and rationale behind such switches to hold their representatives accountable.

Understanding Far-Right Parties: Ideologies, Policies, and Political Impact

You may want to see also

Historical Examples of Party Delays

The concept of party delays in political history is a fascinating lens through which to examine the fluidity and constraints of political affiliations. One notable example is the 1930s Labour Party split in the UK, where Independent Labour Party members faced a six-month waiting period before they could formally join the new Socialist League. This delay was not merely procedural but strategic, allowing the Labour Party to consolidate its base and prevent immediate defections during a period of ideological turmoil. Such historical instances reveal how time delays can serve as both a protective mechanism and a barrier to political realignment.

Consider the post-Civil War Reconstruction era in the United States, where former Confederates were barred from joining the Republican Party for varying periods, often tied to loyalty oaths. This delay was punitive, designed to ensure political and social reintegration on Northern terms. However, it also created a gray area where individuals could nominally align with a party while still harboring conflicting loyalties. This example underscores how time delays can be weaponized to enforce ideological conformity rather than encourage genuine political evolution.

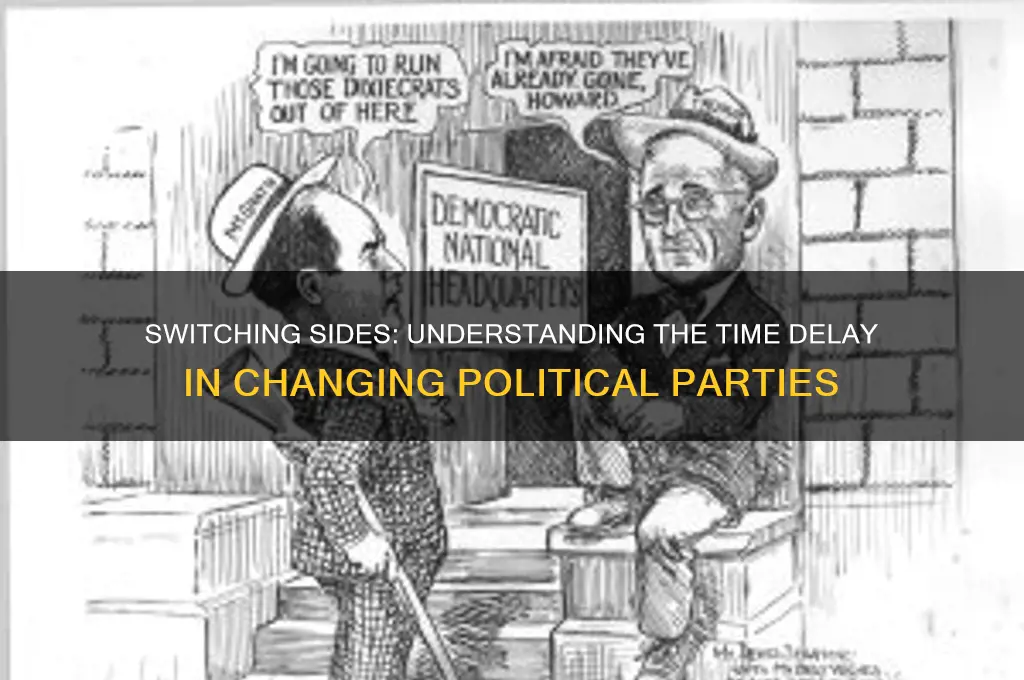

In contrast, the 1960s Democratic Party realignment in the U.S. offers a more fluid example. Southern Democrats, increasingly at odds with the party’s civil rights stance, faced no formal delay in switching to the Republican Party. Yet, the cultural and social inertia of their constituencies created an informal delay, as politicians had to carefully manage public perception before making the switch. This highlights how time delays can arise organically, driven by external pressures rather than internal party rules.

A more recent example is the 2010s UKIP-Conservative Party shift in the UK, where Conservative MPs defecting to UKIP often waited until strategically opportune moments, such as before key elections. While there was no formal delay, the timing of these defections was calculated to maximize impact and minimize backlash. This demonstrates how time delays can be self-imposed, reflecting political pragmatism rather than institutional constraints.

From these examples, a clear takeaway emerges: time delays in party switching are not uniform but are shaped by historical context, institutional rules, and individual strategy. Whether punitive, protective, or pragmatic, these delays play a critical role in shaping political landscapes. Understanding them offers insight into the mechanics of party loyalty and the complexities of political transformation.

Understanding Political Parties: Their Core Objectives and Societal Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The time delay to change political parties varies by country, state, or region, as it is often governed by local election laws. Some jurisdictions require a waiting period, while others allow immediate changes.

The waiting period to change party affiliation depends on local regulations. In some places, it can range from a few days to several months before an election.

In most cases, you cannot change your political party affiliation on election day. Deadlines are typically set well in advance of elections to ensure administrative processes are completed.

Restrictions on how often you can change parties vary. Some jurisdictions allow frequent changes, while others impose limits, such as only permitting changes during specific registration periods.