The concept of a political machine refers to a well-organized, often hierarchical system where a powerful individual or group wields significant influence over a political party or government, typically through patronage, control of resources, and strategic alliances. One of the most notorious examples is Boss Tweed, who ran the Tammany Hall machine in 19th-century New York City, using it to dominate local politics and dispense favors in exchange for loyalty and votes. Similarly, figures like Richard J. Daley in Chicago during the mid-20th century operated a political machine that controlled the Democratic Party and shaped the city’s governance. These machines often blurred the lines between public service and personal gain, leaving a lasting impact on the political landscapes they dominated.

Explore related products

$32.25 $39

What You'll Learn

- Boss Tweed’s Tammany Hall: Controlled 19th-century New York politics through patronage, corruption, and voter influence

- Richard J. Daley’s Chicago: Dominated mid-20th-century Chicago with Democratic Party machine tactics

- William M. Tweed’s Rise: Built Tammany Hall into a powerful political force in NYC

- Machine Politics in Urban Areas: Thrived in cities like Philadelphia, Boston, and St. Louis

- Decline of Political Machines: Weakened by reforms, media scrutiny, and changing voter attitudes

Boss Tweed’s Tammany Hall: Controlled 19th-century New York politics through patronage, corruption, and voter influence

In the mid-19th century, Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall emerged as the quintessential political machine, dominating New York City's political landscape through a combination of patronage, corruption, and voter influence. Led by William M. "Boss" Tweed, Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party's political organization in New York, became a powerhouse by exploiting the city's rapidly growing immigrant population. Tweed and his associates mastered the art of political control, using their influence to secure votes and maintain power. They distributed jobs, favors, and resources to loyal supporters, creating a network of dependency that ensured their electoral dominance. This system of patronage was the backbone of Tammany Hall's control, as it rewarded allies and punished opponents, effectively silencing dissent within the party.

Corruption was another cornerstone of Tammany Hall's operation under Boss Tweed. The organization systematically manipulated city contracts, public works projects, and government funds for personal gain. Tweed and his inner circle, known as the "Tweed Ring," orchestrated massive fraud schemes, inflating the cost of public projects and pocketing the difference. For example, the construction of the New York County Courthouse, which should have cost around $3 million, ended up costing over $13 million due to graft and kickbacks. This rampant corruption enriched Tammany Hall leaders while burdening taxpayers, yet it went largely unchecked due to their political influence and control over law enforcement and the judiciary.

Voter influence was a critical tool in Tammany Hall's arsenal, particularly through its ability to mobilize and manipulate the immigrant vote. Boss Tweed recognized the political potential of New York's burgeoning immigrant population, many of whom were new to the American political system. Tammany Hall provided these immigrants with essential services, such as food, housing, and legal assistance, in exchange for their votes. The organization also employed tactics like voter intimidation, ballot-box stuffing, and repeat voting to ensure favorable election outcomes. By controlling the electoral process, Tammany Hall maintained its grip on power, even in the face of growing opposition.

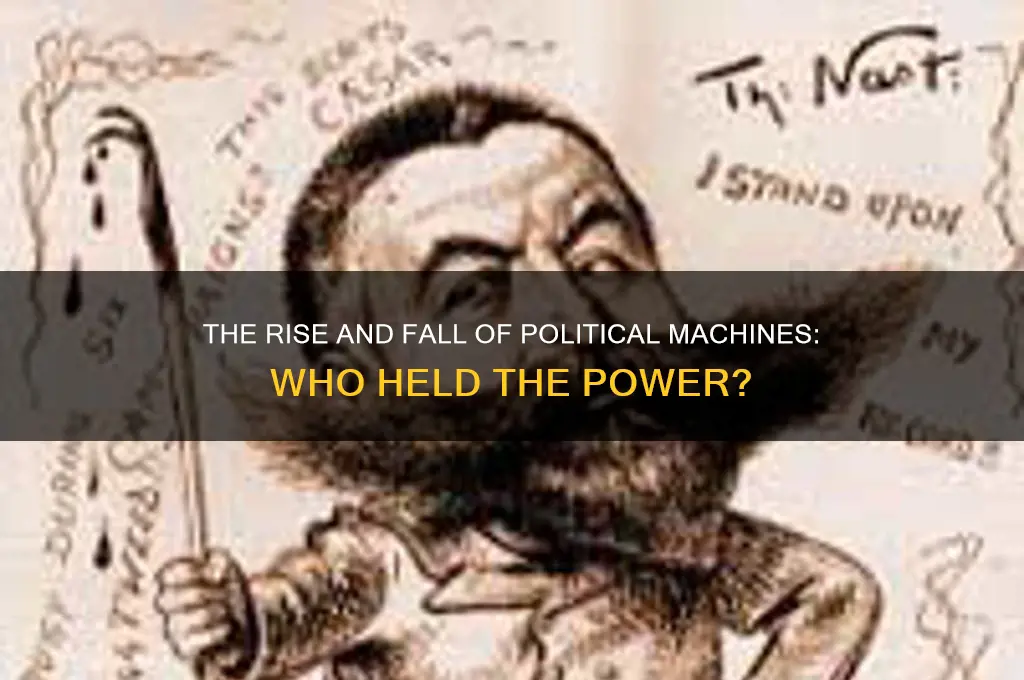

The rise of Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall was not without its critics. Reformers and journalists, most notably Thomas Nast through his scathing political cartoons in *Harper's Weekly*, exposed the corruption and excesses of the Tweed Ring. Nast's illustrations brought public attention to Tammany Hall's misdeeds, galvanizing opposition and ultimately contributing to Tweed's downfall. In 1871, Tweed was arrested and convicted on charges of fraud and corruption, marking the beginning of Tammany Hall's decline. However, the legacy of his political machine endured, shaping the way future political organizations operated in urban America.

Despite its eventual fall, Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall remains a defining example of how a political machine can control a city through patronage, corruption, and voter influence. Its methods were both innovative and exploitative, leveraging the vulnerabilities of a rapidly changing urban society to maintain power. The story of Tammany Hall serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked political power and the importance of transparency and accountability in governance. Through its rise and fall, Tammany Hall underscores the enduring tension between political pragmatism and ethical governance in American history.

Political Parties and Cultural Reform: Coexisting with Revolutionary Movements

You may want to see also

Richard J. Daley’s Chicago: Dominated mid-20th-century Chicago with Democratic Party machine tactics

Richard J. Daley, often referred to as "The Boss," was a towering figure in mid-20th-century American politics, dominating Chicago through his mastery of Democratic Party machine tactics. Serving as mayor from 1955 to 1976, Daley built and maintained a political machine that controlled nearly every aspect of city governance. His power was rooted in a network of patronage, where jobs, contracts, and favors were exchanged for political loyalty and votes. This system ensured that the Democratic Party remained unchallenged in Chicago, solidifying Daley's grip on power. His ability to deliver votes for national Democratic candidates also made him a key player in state and federal politics, earning him influence far beyond the city limits.

Daley's political machine thrived on its organizational efficiency and grassroots reach. Precinct captains, ward committeemen, and local aldermen formed the backbone of the machine, mobilizing voters and ensuring turnout during elections. Daley rewarded these loyalists with city jobs, contracts, and other perks, creating a self-sustaining system of mutual benefit. This structure allowed him to maintain tight control over the city council, labor unions, and even the police department. Critics often accused Daley of prioritizing political loyalty over competence, but the machine's effectiveness in delivering services and maintaining order in a rapidly changing city kept him popular among many Chicagoans.

One of Daley's most notable tactics was his use of patronage to consolidate power. City jobs, from garbage collectors to high-ranking officials, were often awarded based on political allegiance rather than merit. This practice not only ensured loyalty but also created a vast network of supporters who depended on the machine for their livelihoods. Daley's control over city contracts further enriched his allies, fostering a culture of dependency and obedience. While this system was criticized for inefficiency and corruption, it was undeniably effective in maintaining Daley's dominance and the Democratic Party's stranglehold on Chicago.

Daley's leadership was also marked by his ability to balance competing interests within the city. He navigated tensions between racial groups, labor unions, and business leaders, often using his machine to broker compromises that favored his political agenda. During the 1960s, for example, Daley faced significant challenges from the civil rights movement, which exposed the machine's role in perpetuating racial segregation and inequality. Despite these criticisms, Daley's machine remained resilient, adapting to changing demographics and political pressures while maintaining its core structure.

The legacy of Richard J. Daley's political machine is complex and enduring. While his tactics were often undemocratic and exclusionary, they also brought stability and development to Chicago during a tumultuous period. Daley's ability to deliver federal funds and infrastructure projects, such as the construction of O'Hare International Airport, transformed the city into a global hub. However, the machine's reliance on patronage and control ultimately stifled political competition and accountability. Daley's death in 1976 marked the beginning of the machine's decline, but its influence on Chicago's political culture remains evident to this day. His reign as mayor exemplifies the power and pitfalls of political machines in American urban politics.

The Origins of Political Realism: Tracing Its Historical Beginnings

You may want to see also

William M. Tweed’s Rise: Built Tammany Hall into a powerful political force in NYC

William M. Tweed, often referred to as "Boss" Tweed, was a pivotal figure in the history of American political machines, particularly in New York City. His rise to power and his role in transforming Tammany Hall into a dominant political force are emblematic of the era's machine politics. Tweed, born in 1823, began his political career in the 1840s as a volunteer for Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party's political organization in New York City. Through a combination of charisma, organizational skill, and a keen understanding of the city's immigrant populations, Tweed quickly climbed the ranks. By the 1850s, he had become a key figure within Tammany Hall, leveraging his influence to secure patronage jobs and favors for his supporters, which solidified his base of power.

Tweed's ascent was marked by his ability to connect with the working-class and immigrant communities of New York City, particularly the Irish. He recognized that these groups, often marginalized by the city's elite, represented a significant and untapped political resource. Tweed provided them with jobs, legal assistance, and other forms of support, earning their loyalty. This grassroots approach allowed him to build a formidable political machine that could mobilize voters and sway elections. By the 1860s, Tweed had effectively taken control of Tammany Hall, becoming its undisputed leader and the most powerful political boss in New York City.

Under Tweed's leadership, Tammany Hall became a well-oiled political machine, dominating local and state politics. Tweed's control extended to the judiciary, legislature, and city government, enabling him to manipulate contracts, legislation, and appointments for personal and political gain. One of his most notorious achievements was the consolidation of power through the "Tweed Charter," which granted Tammany Hall unprecedented control over New York City's finances and governance. This charter allowed Tweed and his associates to embezzle millions of dollars through fraudulent contracts and inflated construction projects, the most infamous being the construction of the New York County Courthouse, which cost taxpayers an exorbitant amount.

Tweed's influence was not limited to local politics; he also wielded significant power at the state level. As a member of the New York State Senate, he played a crucial role in passing legislation that benefited his machine and its allies. His ability to control both city and state governments made him one of the most powerful political figures in the country. However, Tweed's rise was not without opposition. Reformers and journalists, most notably Thomas Nast of *Harper's Weekly*, began to expose the corruption and excesses of Tweed's regime. Nast's cartoons, in particular, played a key role in turning public opinion against Tweed.

The downfall of Boss Tweed began in the early 1870s, as investigations into Tammany Hall's corruption gained momentum. In 1871, a committee led by Samuel J. Tilden, a prominent Democrat and future presidential candidate, uncovered evidence of Tweed's embezzlement and fraud. Tweed was arrested, tried, and convicted, ultimately serving time in prison. Despite his eventual fall, Tweed's legacy as the architect of one of the most powerful political machines in American history remains intact. His rise and reign illustrate the complexities of machine politics, highlighting both the potential for public service and the dangers of unchecked corruption. Through Tammany Hall, Tweed built a political force that shaped New York City's landscape and left an indelible mark on its history.

How to Change Your Political Party Affiliation in Texas: A Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.39 $15.75

Machine Politics in Urban Areas: Thrived in cities like Philadelphia, Boston, and St. Louis

Machine politics, a system where a tightly organized political organization controls resources and patronage to maintain power, thrived in urban areas during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Cities like Philadelphia, Boston, and St. Louis became fertile ground for these political machines due to their rapidly growing populations, diverse immigrant communities, and the need for local services. In these urban centers, political machines emerged as powerful entities that could deliver jobs, housing, and protection to constituents in exchange for their loyalty and votes. The bosses who ran these machines often wielded immense influence, shaping local and even national politics.

In Philadelphia, the most notorious example of machine politics was the organization led by Boss Matt Quay of the Republican Party. Quay’s machine dominated the city’s politics by controlling patronage jobs, manipulating elections, and ensuring the party’s dominance in Pennsylvania. The machine thrived by catering to the needs of immigrants and working-class citizens, providing them with employment opportunities and basic services in exchange for their political support. This system, while often corrupt, created a sense of stability and security for marginalized communities in a rapidly industrializing city.

Boston was another stronghold of machine politics, with the Democratic Party’s machine led by figures like Martin Lomasney and James Michael Curley. Curley, in particular, was a master of urban politics, using his charisma and ability to connect with Irish immigrants to build a powerful political base. His machine provided jobs, housing, and even coal for the poor during harsh winters, earning him the loyalty of Boston’s working class. While critics accused him of corruption and inefficiency, Curley’s machine effectively addressed the immediate needs of its constituents, solidifying its hold on the city.

St. Louis also saw the rise of machine politics, with the Democratic Party dominating local governance. Boss Tom Pendergast, though primarily associated with Kansas City, exemplifies the type of machine politics that thrived in St. Louis as well. These machines capitalized on the city’s diverse population, particularly immigrants and African Americans, by offering them access to jobs and services in exchange for political loyalty. The machines’ ability to deliver tangible benefits made them indispensable to urban residents, even as they often operated outside the bounds of ethical governance.

The success of machine politics in these cities can be attributed to the unique challenges of urban life during this period. Rapid industrialization and immigration created overcrowded neighborhoods, poor living conditions, and high unemployment. Political machines filled the void left by weak or unresponsive local governments, providing essential services and fostering a sense of community among marginalized groups. However, this system also perpetuated corruption, cronyism, and voter fraud, raising questions about the long-term sustainability of such political structures.

Despite their eventual decline due to reforms and changing political landscapes, the legacy of machine politics in cities like Philadelphia, Boston, and St. Louis remains significant. These machines shaped the urban political landscape, influencing how cities are governed and how politicians interact with their constituents. Their rise and fall offer valuable insights into the complexities of urban governance and the enduring tension between efficiency, corruption, and democratic ideals.

Who Funds Political Rallies? Uncovering the Financial Backers

You may want to see also

Decline of Political Machines: Weakened by reforms, media scrutiny, and changing voter attitudes

The decline of political machines can be attributed to a combination of reforms, increased media scrutiny, and shifting voter attitudes, all of which have significantly weakened their once-dominant influence. Political machines, historically run by powerful figures like Boss Tweed in New York City or Mayor Richard J. Daley in Chicago, thrived by controlling patronage, manipulating elections, and delivering services to loyal constituents. However, the early 20th century marked the beginning of their downfall as progressive reforms targeted the corruption and inefficiency that characterized these systems. The introduction of civil service reforms, such as the Pendleton Act of 1883, replaced patronage-based hiring with merit-based systems, stripping machines of one of their most potent tools for maintaining power.

Media scrutiny played a pivotal role in exposing the malpractices of political machines, further accelerating their decline. Investigative journalism, exemplified by newspapers like *The New York Times* and *The Chicago Tribune*, uncovered instances of graft, fraud, and abuse of power. High-profile exposés not only informed the public but also pressured lawmakers to enact stricter regulations. The rise of broadcast media in the mid-20th century amplified these efforts, as television brought political corruption into the living rooms of millions, making it harder for machines to operate in the shadows. This increased transparency eroded public trust in machine politics, making it more difficult for them to maintain their grip on power.

Changing voter attitudes also contributed to the weakening of political machines. As education levels rose and urbanization transformed societies, voters became more informed and less reliant on machine-provided services. The post-World War II era saw a shift toward issue-based voting, with citizens prioritizing policy over personal favors. Additionally, the civil rights movement and other social justice campaigns fostered a demand for more equitable and transparent governance, further marginalizing the exclusionary practices of political machines. These shifts in voter expectations made it increasingly challenging for machines to sustain their traditional methods of control.

Reforms at the local, state, and federal levels dealt additional blows to political machines. Campaign finance laws, such as the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, limited the ability of machines to funnel money into elections unchecked. Voting rights legislation, including the Voting Rights Act of 1965, expanded access to the ballot, diluting the influence of machine-controlled blocs. Furthermore, the professionalization of government and the rise of independent regulatory agencies reduced opportunities for machine interference in public administration. These structural changes systematically dismantled the frameworks that had allowed political machines to flourish.

In conclusion, the decline of political machines was driven by a convergence of factors: reforms that curtailed patronage and corruption, media scrutiny that exposed their misdeeds, and changing voter attitudes that demanded greater accountability. While remnants of machine politics still exist in some areas, their influence has been vastly diminished. The legacy of this decline is a more transparent and democratic political landscape, though it also raises questions about the role of local intermediaries in representing marginalized communities. Understanding this transformation is crucial for analyzing contemporary political systems and the ongoing struggle for equitable governance.

Are Political Parties Still Relevant in Today's Changing Political Landscape?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Boss William Tweed, also known as "Boss Tweed," was the most notorious leader of Tammany Hall, controlling it in the mid-1800s.

Richard J. Daley, mayor of Chicago from 1955 to 1976, was the central figure in running the powerful political machine.

Thomas "Tom" Pendergast was the boss of the Pendergast machine, which dominated Kansas City politics in the 1920s and 1930s.

Matthew Quay, a U.S. Senator and political boss, controlled the Pennsylvania Republican machine in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Harry F. Byrd Sr., a U.S. Senator and Governor of Virginia, ran the Byrd Organization, which dominated Virginia politics for much of the 20th century.