The concept of a government without political parties challenges traditional notions of democratic governance, as political parties are often seen as essential for organizing political competition, aggregating interests, and facilitating representation. However, there are instances where governments operate without formal party structures, such as in non-partisan democracies or technocratic regimes. These systems often rely on independent candidates, consensus-building, or expertise-driven decision-making rather than party affiliations. Examples include Singapore’s dominant-party system with limited opposition, or local governments in the United States where elections are officially non-partisan. The question of whether such systems can truly function without underlying political factions or informal groupings remains a subject of debate, as human political behavior tends to gravitate toward coalition-building and ideological alignment, even in the absence of formal parties.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Existence | Yes, governments without formal political parties do exist. |

| Examples | Micronesia, Palau, Tuvalu, Nauru, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Honduras (historically), Panama (historically), and some city governments (e.g., Los Angeles Unified School District Board of Education). |

| System Type | Non-partisan democracy, technocracy, or consensus-based governance. |

| Decision-Making | Decisions are often made based on consensus, expertise, or direct citizen participation rather than party lines. |

| Elections | Candidates run as independents, without party affiliations, focusing on personal platforms or community issues. |

| Advantages | Reduced polarization, focus on local or national issues rather than party ideology, and potential for more pragmatic decision-making. |

| Challenges | Lack of structured opposition, difficulty in forming stable coalitions, and potential for weaker accountability mechanisms. |

| Stability | Can be stable if there is a strong culture of consensus-building and civic engagement. |

| Citizen Engagement | Often relies on high levels of citizen participation and direct democracy mechanisms. |

| Historical Context | Some countries have transitioned away from party-based systems due to historical or cultural factors, while others have never adopted them. |

| Global Prevalence | Relatively rare, with most democratic governments operating within a multi-party system. |

Explore related products

$17.49 $26

$28.31 $42

What You'll Learn

Historical examples of non-partisan governments

Throughout history, several governments have operated without formal political parties, often relying on consensus-building, technocratic expertise, or traditional authority structures. One notable example is the Swiss Federal Council, which, while not entirely non-partisan, functions on a unique model of concordance democracy. Political parties are represented proportionally, but council members are expected to set aside party loyalties and govern collectively. This system minimizes partisan conflict and prioritizes stability, offering a hybrid approach to non-partisan governance.

In contrast, ancient Athens provides a purely non-partisan historical example. Athenian democracy operated through direct citizen participation, with officials selected by lot rather than elected based on party affiliation. This system, while limited to male citizens, eliminated party politics entirely, relying instead on collective decision-making and civic duty. Its success hinged on small-scale governance and a shared cultural identity, factors difficult to replicate in modern nation-states.

The Sultanate of Brunei offers a contemporary example of non-partisan governance rooted in tradition. Here, the monarch serves as both head of state and government, with no political parties in existence. Decision-making is centralized and based on Islamic law and customary practices. While this model ensures stability, it lacks the pluralism and accountability often associated with democratic systems, highlighting the trade-offs of non-partisan rule.

Finally, post-apartheid South Africa briefly experimented with non-partisan governance during its transition to democracy. The Government of National Unity (1994–1996) included parties based on proportional representation but emphasized reconciliation over partisan competition. This temporary arrangement laid the groundwork for a more inclusive political system, demonstrating how non-partisan principles can facilitate healing in divided societies.

These examples reveal that non-partisan governments can take diverse forms, from direct democracy to monarchical rule and transitional arrangements. While they often prioritize stability and unity, their success depends on contextual factors such as scale, cultural cohesion, and the presence of alternative accountability mechanisms. For modern policymakers, these historical cases offer valuable lessons on balancing partisanship with effective governance.

The Federalist Party's Reign: Unveiling 1796's Political Leadership

You may want to see also

Role of independent candidates in governance

Independent candidates, free from party affiliations, can inject a unique dynamism into governance by prioritizing local issues over partisan agendas. Consider the case of Michael Bloomberg, who governed New York City as an independent, focusing on pragmatic solutions like crime reduction and economic revitalization rather than ideological battles. This approach allows independents to act as bridges between polarized factions, fostering collaboration in divided legislatures. For instance, in the U.S. Senate, Angus King and Bernie Sanders, both independents, often broker compromises by aligning with either party based on issue merit rather than loyalty. This issue-driven governance can lead to more targeted policies, such as King’s work on rural broadband expansion, which transcends party lines.

However, the effectiveness of independent candidates hinges on their ability to navigate structural barriers. Without party backing, they face challenges in fundraising, media coverage, and coalition-building. In the UK, independent MP Martin Bell won a seat in 1997 by campaigning against corruption, but his influence was limited by lack of party support. To overcome this, independents must cultivate strong grassroots networks and leverage digital platforms to amplify their message. For example, crowdfunding campaigns can offset financial disadvantages, while social media allows direct engagement with voters. Practical tips for independents include focusing on hyper-local issues, such as school funding or infrastructure, which resonate deeply with constituents and demonstrate tangible impact.

A comparative analysis reveals that independents thrive in systems with proportional representation or mixed-member districts, where smaller parties and unaffiliated candidates have a better chance of winning seats. In New Zealand’s mixed-member proportional system, independents like Peter Dunne have held significant influence by aligning with governing coalitions. Conversely, in winner-take-all systems like the U.S., independents often struggle to gain traction. This suggests that electoral reform, such as ranked-choice voting, could enhance the role of independents by reducing the spoiler effect and encouraging broader voter engagement.

Persuasively, the inclusion of independent candidates enriches democratic governance by diversifying perspectives and reducing partisan gridlock. Their presence forces parties to address neglected issues and adopt more inclusive policies. For instance, in India, independent candidates often represent marginalized communities, bringing their concerns to the forefront of legislative debates. To maximize their impact, independents should focus on building cross-party alliances on specific issues, such as climate change or healthcare reform, where consensus is achievable. By doing so, they can act as catalysts for meaningful change, proving that governance need not be monopolized by political parties.

In conclusion, while independent candidates face structural hurdles, their role in governance is invaluable for fostering pragmatism and inclusivity. By focusing on local issues, leveraging technology, and advocating for electoral reforms, independents can overcome barriers and contribute significantly to policy-making. Their success lies in their ability to remain issue-driven, adaptable, and responsive to constituent needs, offering a compelling alternative to party-dominated politics.

Legitimacy of Political Power: Exploring Justifications for Authority

You may want to see also

Technocracy vs. party-based systems

Technocracy, a system where decision-making is in the hands of technical experts and scientists rather than politicians, stands in stark contrast to party-based systems that dominate global governance. In a technocracy, policies are shaped by data, research, and specialized knowledge, not by ideological platforms or electoral promises. For instance, Singapore’s governance model, while not a pure technocracy, incorporates elements of this approach, with a heavy reliance on technocratic expertise in areas like urban planning and economic policy. This model prioritizes efficiency and problem-solving over political maneuvering, raising the question: could such a system eliminate the polarization and gridlock inherent in party-based politics?

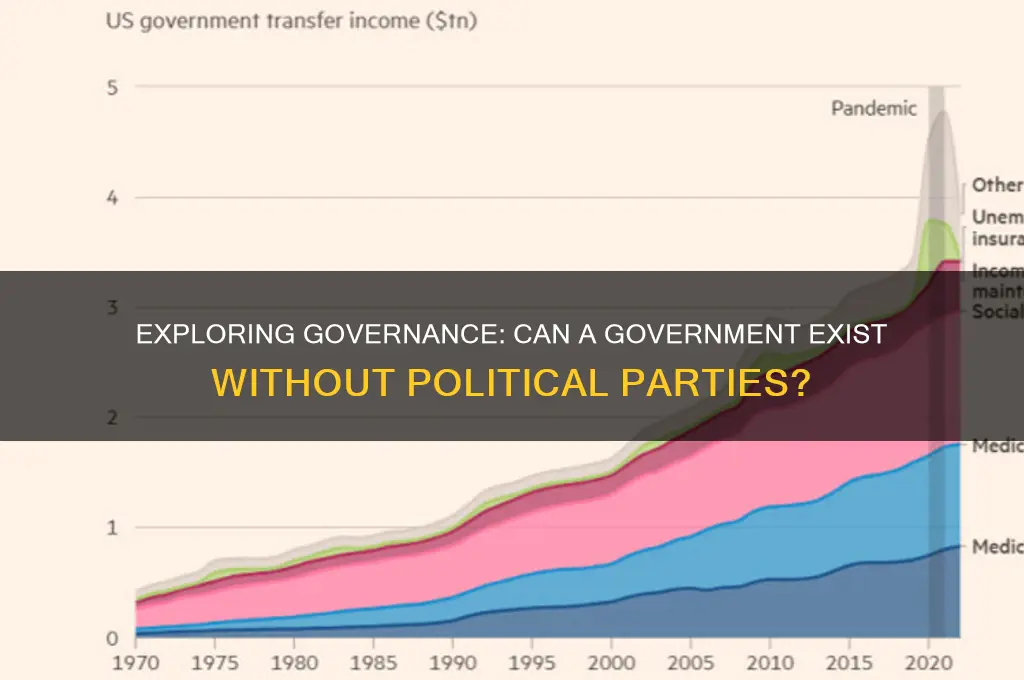

Consider the practical implications of transitioning to a technocracy. In a party-based system, policies often reflect the interests of the party in power, leading to short-termism and inconsistent long-term planning. Technocracy, by contrast, could ensure continuity and evidence-based decision-making. For example, climate policy in a technocracy might be driven by scientists and engineers, resulting in consistent, data-backed strategies rather than fluctuating commitments based on election cycles. However, this approach requires a robust mechanism for selecting experts, free from bias or influence, to maintain legitimacy.

Critics argue that technocracy risks sidelining public opinion and democratic participation. In a party-based system, elections serve as a check on power and a means for citizens to voice their preferences. Technocracy, without such mechanisms, could lead to an elitist governance structure where decisions are made without public input. To address this, a hybrid model could be explored, where technocratic bodies advise elected representatives, ensuring both expertise and accountability. For instance, the European Commission’s use of scientific committees to inform policy is a step in this direction, though it remains within a broader party-based framework.

Implementing a technocratic system also requires addressing the challenge of expertise in an era of rapid technological change. As fields like artificial intelligence and biotechnology evolve, the pool of relevant experts must continually adapt. This dynamic nature of expertise contrasts sharply with the static structures of party-based systems, where politicians may lack the specialized knowledge needed to govern effectively. A technocracy, therefore, must include mechanisms for ongoing education and integration of new expertise, ensuring that decision-makers remain at the forefront of their fields.

Ultimately, the debate between technocracy and party-based systems hinges on balancing efficiency with democratic values. While technocracy offers the promise of evidence-driven governance, it must be designed to incorporate public input and adapt to changing expertise. Party-based systems, despite their flaws, provide a platform for diverse voices and political participation. The ideal may not be to replace one with the other but to integrate their strengths, creating a governance model that leverages expertise while preserving democratic principles. This hybrid approach could offer a path forward in addressing the complexities of modern governance.

Unraveling the Origins: Tracing the Roots of Political Systems and Ideas

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Direct democracy as an alternative model

Direct democracy, where citizens directly participate in decision-making rather than electing representatives, offers a compelling alternative to party-based governance. This model eliminates the intermediary role of political parties, allowing voters to propose, debate, and enact laws themselves. Switzerland stands as the most prominent example, where citizens regularly vote on national and local issues through referendums, initiatives, and recalls. This system bypasses party politics, ensuring decisions reflect the immediate will of the people rather than partisan agendas.

Implementing direct democracy requires careful design to avoid pitfalls. First, establish clear thresholds for citizen-led initiatives to prevent frivolous proposals. For instance, Switzerland mandates 100,000 signatures within 18 months for a federal initiative. Second, invest in civic education to ensure voters understand complex issues. Third, leverage technology for accessible voting platforms, as Estonia has done with its e-voting system. Without these safeguards, direct democracy risks becoming chaotic or dominated by vocal minorities.

Critics argue direct democracy is impractical for large, diverse populations, but evidence suggests otherwise. In California, a state with nearly 40 million residents, ballot initiatives have addressed issues from taxation to environmental policy. While not all outcomes are perfect, the process fosters greater civic engagement and accountability. For smaller communities, direct democracy can be even more effective, as seen in New England town meetings, where residents gather annually to vote on local budgets and policies.

Adopting direct democracy as a model requires a cultural shift toward active citizenship. It demands time, attention, and willingness to engage in public discourse. However, the benefits—reduced partisan polarization, increased transparency, and direct control over governance—make it a worthy alternative. For nations weary of party-driven politics, direct democracy offers a path to re-center government around the people’s voice, not party interests.

Socrates' Political Absence: Exploring the Realms He Never Entered

You may want to see also

Challenges of coalition-free administrations

Governments without political parties, though rare, exist in various forms, such as non-partisan democracies or technocratic administrations. These systems often aim to reduce ideological polarization and prioritize expertise over party loyalty. However, coalition-free administrations face distinct challenges that can undermine their effectiveness and stability. Understanding these hurdles is crucial for evaluating their viability in modern governance.

One of the primary challenges is the lack of a unified policy framework. Political parties typically provide a cohesive agenda, streamlining decision-making and legislative processes. In their absence, coalition-free governments must rely on ad-hoc consensus-building, which can lead to policy fragmentation. For instance, independent legislators or technocrats may prioritize their constituencies or expertise over national interests, resulting in disjointed initiatives. This inconsistency can hinder long-term planning and public trust, as citizens may perceive the government as directionless or reactive rather than proactive.

Another significant obstacle is the difficulty of maintaining stability in the absence of party discipline. Political parties enforce cohesion through internal mechanisms, ensuring members vote along party lines. Without this structure, coalition-free administrations risk frequent legislative gridlock or unpredictable outcomes. A case in point is the 2019 Italian government, which, despite being technocratic in nature, struggled to pass key reforms due to conflicting interests among independent ministers. Such instability can deter foreign investment and weaken a government’s ability to respond to crises effectively.

Moreover, coalition-free governments often face challenges in fostering public engagement and accountability. Political parties serve as intermediaries between the government and the electorate, mobilizing support and channeling public opinion. Without this intermediary role, coalition-free administrations may struggle to communicate their vision or secure broad-based legitimacy. For example, non-partisan governments in small island nations like Palau have sometimes been criticized for appearing distant or elitist, as their technocratic focus may alienate less educated or marginalized communities.

To mitigate these challenges, coalition-free administrations must adopt innovative strategies. Establishing robust consultative mechanisms, such as citizen assemblies or expert panels, can help bridge the gap between governance and public participation. Additionally, fostering a culture of collaboration among independent actors, possibly through incentives for bipartisan cooperation, can reduce legislative stagnation. Finally, transparent communication and regular performance evaluations can enhance accountability, ensuring that technocratic or non-partisan governments remain responsive to societal needs. While coalition-free administrations offer a unique approach to governance, their success hinges on addressing these inherent challenges with creativity and adaptability.

Understanding BRX: Which European Political Party Does It Align With?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, it is possible. Some governments operate without formal political parties, relying instead on non-partisan systems, technocratic leadership, or consensus-based decision-making.

Examples include Singapore, where the dominant party system is often described as non-partisan in practice, and certain local or municipal governments that operate on a non-partisan basis.

Such governments often rely on technocratic expertise, public consultation, or consensus-building among stakeholders to make decisions, rather than party-based ideologies.

Efficiency and effectiveness depend on context. Non-partisan governments may avoid partisan gridlock but can lack the diversity of perspectives that political parties bring.

Yes, a democracy can function without political parties through mechanisms like direct democracy, independent candidates, or issue-based coalitions, though this is less common in large-scale systems.