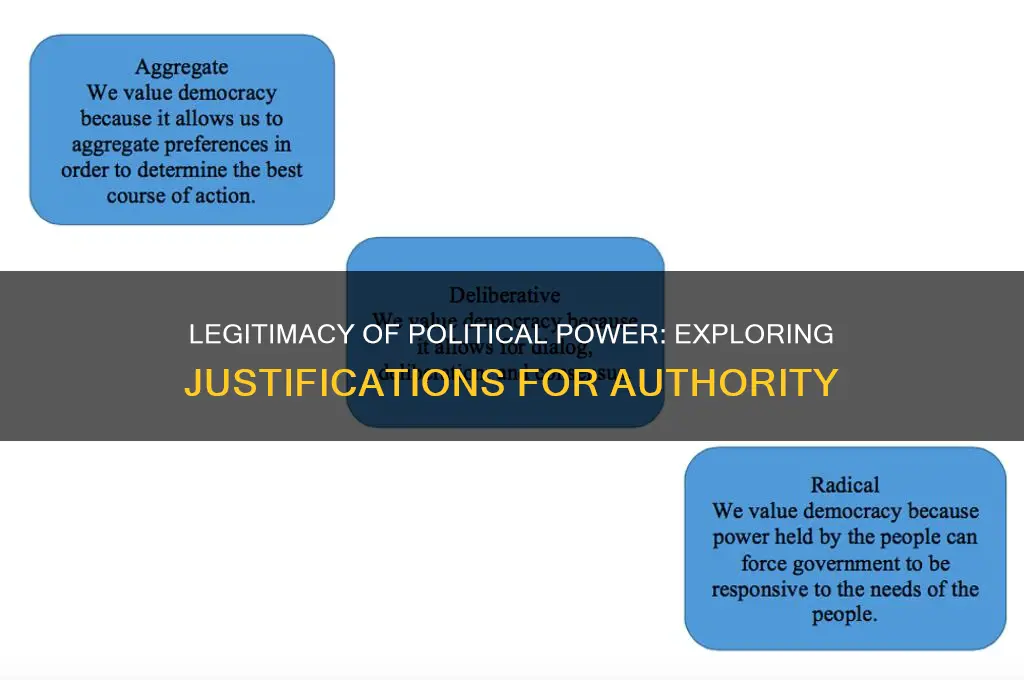

The question of what justifies political authority is a cornerstone of political philosophy, probing the legitimacy of governments and their right to wield power over individuals. At its core, this inquiry seeks to reconcile the tension between individual autonomy and collective governance, asking under what conditions, if any, it is morally acceptable for a state to impose rules and enforce compliance. Theories range from consent-based models, such as social contract theory, which argue that authority is justified when individuals implicitly or explicitly agree to it, to utilitarian perspectives, which emphasize the role of authority in maximizing societal welfare. Other approaches, like those rooted in natural law or divine right, posit that authority derives from higher principles or divine ordination. Ultimately, the justification of political authority hinges on balancing the need for order and stability with the protection of individual rights and freedoms, a challenge that continues to shape political discourse and practice in diverse societies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Consent of the Governed | Legitimacy derived from the voluntary agreement of citizens, often through elections or social contracts. |

| Social Contract Theory | Authority is justified when it upholds mutual agreements between the state and its citizens, ensuring protection and order in exchange for obedience. |

| Justice and Fairness | Authority is justified if it ensures equitable distribution of resources, equal treatment under the law, and protection of rights. |

| Effectiveness and Stability | Authority is justified if it maintains social order, provides public goods, and ensures security and stability. |

| Moral and Ethical Foundations | Authority is justified if it aligns with moral principles, such as protecting human rights, promoting the common good, and upholding ethical standards. |

| Accountability and Transparency | Authority is justified if it is accountable to the people, operates transparently, and is subject to checks and balances. |

| Legitimacy through Tradition or History | Authority is justified by historical continuity, cultural norms, or established traditions that are widely accepted. |

| Legal and Constitutional Frameworks | Authority is justified if it operates within established laws, constitutions, and institutional frameworks that define its powers and limits. |

| Protection of Individual Rights | Authority is justified if it safeguards individual freedoms, such as speech, religion, and property, while preventing tyranny. |

| Public Trust and Legitimacy | Authority is justified if it maintains the trust of the populace through consistent, fair, and responsive governance. |

Explore related products

$53.99 $109.99

$29.95 $29.95

What You'll Learn

- Consent of the governed: Legitimacy through voluntary agreement and participation in political decision-making processes

- Social contract theory: Authority derived from implicit or explicit agreements among individuals for mutual benefit

- Utilitarian justification: Authority is valid if it maximizes overall societal welfare and minimizes harm

- Natural law and morality: Political authority grounded in universal moral principles and divine or natural order

- Historical and traditional legitimacy: Authority justified by long-standing customs, traditions, and historical continuity

Consent of the governed: Legitimacy through voluntary agreement and participation in political decision-making processes

The concept of "consent of the governed" is a cornerstone in justifying political authority, emphasizing that legitimate power arises from the voluntary agreement of those being governed. This principle suggests that individuals willingly submit to authority when they perceive it as fair, representative, and aligned with their interests. At its core, this idea challenges the notion of coercion as the basis for governance, instead advocating for a system where authority is derived from the active participation and approval of the citizenry. This approach not only fosters legitimacy but also ensures that political institutions remain accountable to the people they serve.

Voluntary agreement is the foundation of this justification for political authority. It implies that individuals consent to be governed under certain terms, often formalized through social contracts, constitutions, or democratic processes. For example, in democratic societies, citizens implicitly or explicitly consent to the authority of elected representatives by participating in elections, referendums, or public consultations. This consent is not a one-time transaction but an ongoing process, as citizens continually engage with political systems through voting, activism, and public discourse. When governance aligns with the collective will of the people, it gains moral and practical legitimacy, reinforcing the authority of the state.

Participation in political decision-making processes is another critical aspect of this justification. Legitimacy is not merely about obtaining initial consent but also about ensuring that citizens have a meaningful role in shaping policies and decisions that affect their lives. This participation can take various forms, including voting, joining political parties, engaging in civil society organizations, or contributing to public debates. Inclusive and transparent decision-making processes empower citizens, making them stakeholders in the governance system. When people see their voices reflected in policy outcomes, they are more likely to view the political authority as legitimate and worthy of their continued support.

However, the principle of consent of the governed is not without challenges. One major issue is ensuring that consent is truly informed and voluntary, rather than coerced or manipulated. This requires an environment where citizens have access to accurate information, freedom of expression, and protection from undue influence. Additionally, the diversity of opinions within a population complicates the idea of unanimous consent, necessitating mechanisms like majority rule, minority rights protections, and consensus-building to ensure fairness. Addressing these challenges is essential for maintaining the legitimacy of political authority in a pluralistic society.

In conclusion, the consent of the governed justifies political authority by grounding it in voluntary agreement and active participation. This principle shifts the focus from power imposed from above to authority derived from the collective will of the people. By fostering inclusive decision-making processes and ensuring that consent is informed and voluntary, political systems can achieve and sustain legitimacy. Ultimately, this approach not only strengthens the moral foundation of governance but also promotes stability, accountability, and responsiveness in political institutions.

NBC's Political Leanings: Uncovering the Network's Ideological Stance

You may want to see also

Social contract theory: Authority derived from implicit or explicit agreements among individuals for mutual benefit

Social contract theory is a foundational concept in political philosophy that posits political authority is justified through agreements—either implicit or explicit—among individuals who consent to form a society for mutual benefit. At its core, this theory suggests that humans originally lived in a "state of nature," a hypothetical condition where there was no established authority or organized society. In this state, individuals were free but faced challenges such as insecurity, conflict, and limited cooperation. To overcome these challenges, people entered into a social contract, voluntarily agreeing to establish a political authority that would protect their rights and ensure stability in exchange for their compliance with its rules.

The explicit form of the social contract is often associated with philosophers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, each of whom interpreted the agreement differently. Hobbes argued that individuals consented to absolute authority to escape the "war of all against all" in the state of nature. Locke, on the other hand, emphasized a limited government that protects natural rights, such as life, liberty, and property, and suggested that individuals could revoke their consent if the government failed to fulfill its obligations. Rousseau proposed a more democratic interpretation, where the general will of the people, rather than a ruler, constitutes the sovereign authority. Despite their differences, all these thinkers agreed that political authority is legitimate only if it arises from the consent of the governed.

Implicit social contracts, while less formal, are equally important in justifying political authority. These agreements are unwritten and often inferred from societal norms, traditions, and shared expectations. For example, citizens in a democracy implicitly agree to abide by the rule of law and respect the outcomes of elections, even if their preferred candidate does not win. This implicit consent is based on the understanding that the system, though imperfect, provides greater overall benefits than chaos or anarchy. Implicit contracts also reflect a sense of reciprocity, where individuals accept authority in exchange for public goods like security, infrastructure, and social services.

A key strength of social contract theory is its emphasis on mutual benefit and reciprocity. By framing political authority as a collective agreement, it ensures that governments are accountable to the people they govern. This accountability is crucial for maintaining legitimacy, as it reminds rulers that their power is derived from and contingent upon the consent of the governed. Moreover, the theory provides a normative framework for evaluating the justness of political systems: any authority that fails to uphold its end of the bargain—whether by violating rights, neglecting public welfare, or acting tyrannically—loses its moral justification.

However, social contract theory is not without its criticisms. One challenge is determining how consent is established, especially in large, diverse societies where explicit agreements are impractical. Critics argue that many individuals do not actively consent to the political systems they are born into, raising questions about the theory’s applicability in modern nation-states. Additionally, the theory assumes a degree of equality among individuals in the state of nature, which may not reflect historical or contemporary power dynamics. Despite these challenges, social contract theory remains a powerful tool for understanding and justifying political authority, as it underscores the importance of consent, mutual benefit, and the social nature of human existence.

CBN's Political Stance: Unraveling Its Ideological Position and Influence

You may want to see also

Utilitarian justification: Authority is valid if it maximizes overall societal welfare and minimizes harm

The utilitarian justification for political authority centers on the principle that legitimate authority must maximize overall societal welfare and minimize harm. This perspective, rooted in utilitarian philosophy, evaluates the moral worth of actions and institutions based on their consequences. In the context of political authority, this means that governments or ruling bodies are justified in their power only if their decisions and policies lead to the greatest good for the greatest number of people. This approach shifts the focus from abstract rights or contractual agreements to tangible outcomes, making it a pragmatic and results-oriented framework for justifying authority.

To operationalize this justification, utilitarianism requires that political authority systematically assess the impact of its actions on societal welfare. This involves weighing the benefits and harms of policies across the population, ensuring that the net positive outcome is maximized. For example, a government might implement progressive taxation to redistribute wealth, reduce poverty, and improve access to education and healthcare. While such policies may impose burdens on higher-income individuals, the overall increase in societal welfare—such as reduced inequality and improved public health—justifies the authority’s actions under utilitarian principles. The key is that the benefits outweigh the costs when considered across the entire population.

A critical aspect of the utilitarian justification is its emphasis on impartiality and the equal consideration of interests. Political authority must treat every individual’s welfare as equally important, avoiding favoritism or discrimination. This impartiality ensures that decisions are made based on the collective good rather than the interests of a particular group. For instance, policies addressing climate change may require sacrifices from industries reliant on fossil fuels, but the long-term benefits of environmental preservation and public health justify these measures. Utilitarianism demands that authority prioritize the greater good, even if it means imposing short-term costs on specific sectors or individuals.

However, the utilitarian justification is not without challenges. One major concern is the potential for the majority’s welfare to overshadow the rights or interests of minorities. If a policy benefits a large population at the expense of a smaller, marginalized group, utilitarianism might justify it, raising ethical questions about fairness and justice. To address this, proponents argue that true maximization of welfare requires protecting the vulnerable and ensuring that no group is systematically disadvantaged. Thus, utilitarian authority must balance aggregate welfare with the equitable distribution of benefits and burdens.

In practice, implementing utilitarian justification requires robust mechanisms for measuring and comparing welfare outcomes. This includes data-driven policymaking, cost-benefit analyses, and public consultation to understand diverse needs and preferences. Additionally, transparency and accountability are essential to ensure that authority acts in the best interest of society. For example, governments might use surveys, economic indicators, and health metrics to assess the impact of their policies and adjust them accordingly. By grounding authority in evidence and outcomes, utilitarianism provides a dynamic and adaptive framework for governance.

In conclusion, the utilitarian justification for political authority hinges on its ability to maximize societal welfare and minimize harm. This approach prioritizes consequences over intentions, demanding that authority act impartially and focus on the greater good. While it offers a pragmatic and outcome-oriented basis for legitimacy, it also requires careful attention to equity and the protection of minority interests. When implemented with transparency and accountability, utilitarian principles can provide a robust foundation for justifying political authority in a complex and diverse society.

Do Political Parties Wield Excessive Power in Modern Democracies?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Natural law and morality: Political authority grounded in universal moral principles and divine or natural order

The concept of natural law and morality as a justification for political authority is rooted in the belief that certain moral principles are universally applicable and inherently binding on all individuals. This perspective posits that political authority is legitimate when it aligns with these universal moral principles, which are often seen as derived from a divine or natural order. Proponents of this view argue that governments and rulers derive their authority from their ability to uphold and enforce these moral standards, ensuring justice, fairness, and the common good. This approach to political authority is deeply intertwined with philosophical and theological traditions, emphasizing the existence of an objective moral framework that transcends human-made laws.

One of the key figures associated with natural law theory is Thomas Aquinas, who integrated Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology. Aquinas argued that natural law is a reflection of divine reason, accessible to human reason through observation and reflection on the natural order. According to this view, political authority is justified when it conforms to the rational principles of natural law, which include the protection of life, the pursuit of the common good, and the promotion of virtue. Governments that fail to uphold these principles are seen as illegitimate, as they deviate from the moral order that underpins human existence. This perspective provides a normative framework for evaluating political systems, emphasizing the importance of moral integrity in governance.

The idea of political authority grounded in natural law and morality also has significant implications for the relationship between law and ethics. In this framework, human-made laws are valid only insofar as they reflect the higher principles of natural law. Laws that contradict these universal moral standards are considered unjust and do not bind the conscience. This perspective has been influential in shaping legal and political thought, particularly in the development of concepts such as human rights and the rule of law. For example, the Declaration of Independence asserts that all individuals are endowed with certain unalienable rights derived from their Creator, a clear echo of natural law theory. This understanding of rights as inherent and universal provides a moral foundation for political authority, anchoring it in principles that transcend the contingencies of time and place.

Critics of natural law and morality as a justification for political authority often challenge the objectivity and universality of the moral principles it invokes. They argue that what constitutes the "natural order" or "divine reason" is subject to interpretation and can vary widely across cultures and historical periods. This relativistic critique questions the feasibility of grounding political authority in a fixed moral framework, particularly in a diverse and pluralistic society. Additionally, skeptics point out the potential for abuse when political power is justified on the basis of moral or religious claims, as it can lead to the imposition of particular values on others under the guise of universality. These challenges highlight the need for careful consideration of how natural law principles are applied in practice, ensuring that they remain inclusive and respectful of human dignity.

Despite these criticisms, the appeal of natural law and morality as a justification for political authority endures, particularly among those who seek a stable and objective foundation for governance. This perspective offers a compelling alternative to purely utilitarian or contractual theories of political legitimacy, emphasizing the intrinsic value of moral principles in shaping just societies. By grounding political authority in a universal moral order, it provides a framework for addressing issues of justice, rights, and the common good in a way that transcends individual interests or societal conventions. For those who adhere to this view, the alignment of political power with natural law and morality is not only a matter of legitimacy but also a moral imperative, essential for the flourishing of individuals and communities alike.

Understanding the Socio-Political Climate: Influences, Impacts, and Implications

You may want to see also

Historical and traditional legitimacy: Authority justified by long-standing customs, traditions, and historical continuity

Historical and traditional legitimacy serves as a cornerstone for political authority in many societies, grounding governance in the enduring power of customs, traditions, and historical continuity. This form of legitimacy asserts that political authority is justified because it is rooted in practices and institutions that have been accepted and followed over generations. Such continuity provides stability and a sense of collective identity, making it a compelling basis for rule. For instance, monarchies often derive their authority from centuries-old traditions, claiming a divine or historical right to govern that transcends individual rulers. This approach emphasizes the importance of preserving established norms and structures, even in the face of change, as a means of maintaining social order.

One of the key strengths of historical and traditional legitimacy is its ability to foster a shared sense of heritage and belonging among citizens. By anchoring authority in long-standing customs, it creates a narrative of continuity that connects the present to the past. This connection can be particularly powerful in societies with strong cultural or religious traditions, where adherence to historical norms is seen as a moral or sacred duty. For example, in many Asian and African societies, traditional leadership structures, such as chieftaincies or tribal councils, remain influential because they are deeply embedded in local customs and are perceived as legitimate by the community. This form of legitimacy relies on the collective memory and shared values of a people, making it resilient to external challenges.

However, historical and traditional legitimacy is not without its limitations. Critics argue that it can perpetuate outdated or unjust practices simply because they are old, rather than because they are fair or effective. For instance, traditions that marginalize certain groups, such as women or minorities, may continue to be upheld under the guise of preserving historical continuity. This raises questions about the compatibility of traditional legitimacy with modern principles of equality and human rights. Additionally, in an era of rapid globalization and cultural change, the relevance of historical traditions as a basis for authority may be increasingly contested, particularly among younger generations who prioritize innovation over continuity.

Despite these challenges, historical and traditional legitimacy remains a vital source of political authority in many parts of the world. It is often complemented by other forms of legitimacy, such as legal or charismatic authority, to create a more robust foundation for governance. For example, constitutional monarchies blend traditional legitimacy with legal frameworks, ensuring that historical continuity is balanced with modern democratic principles. Similarly, in countries with diverse populations, traditional practices may be adapted to reflect contemporary values, allowing historical legitimacy to remain relevant while addressing societal changes.

In conclusion, historical and traditional legitimacy justifies political authority by appealing to the enduring power of customs, traditions, and historical continuity. It provides a sense of stability, identity, and moral purpose, particularly in societies where cultural heritage is deeply valued. While it faces challenges in adapting to modern norms and ensuring fairness, its resilience lies in its ability to connect the present with the past, offering a foundation for governance that transcends individual leaders or transient ideologies. As such, it continues to play a significant role in shaping political authority across diverse contexts.

Tracing the Origins of Hate Politics: A Historical Perspective

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The social contract theory, proposed by thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, argues that individuals agree to form a society and government by consent, surrendering some freedoms in exchange for protection and order. This mutual agreement justifies political authority as a necessary mechanism to ensure collective security and well-being.

Legitimacy refers to the perception that a government’s authority is rightful and justified. It can be based on factors like democratic elections, adherence to the rule of law, or alignment with shared values. When a government is seen as legitimate, its authority is justified because it reflects the will or consent of the governed.

Yes, one justification for political authority is its role in maintaining social order and preventing chaos. Governments enforce laws, resolve disputes, and provide public goods, which are essential for societal stability. This utilitarian argument suggests that authority is justified if it maximizes overall security and prosperity.

Moral and ethical reasoning can justify political authority if the government acts in accordance with principles of justice, fairness, and the common good. For example, authority may be justified if it protects human rights, promotes equality, or ensures the welfare of its citizens, aligning with ethical standards.