The question of whether the solution to contemporary political challenges lies in having more political parties or fewer is a complex and contentious issue. On one hand, proponents of increasing the number of parties argue that it fosters greater representation, encourages diverse perspectives, and reduces the dominance of established elites, thereby making political systems more inclusive and responsive to varied societal needs. Conversely, advocates for fewer parties contend that a streamlined party system can enhance stability, reduce polarization, and facilitate more efficient governance by minimizing ideological fragmentation. This debate is further complicated by contextual factors such as a nation's political culture, electoral systems, and historical experiences, which significantly influence the outcomes of party proliferation or consolidation. Ultimately, the ideal number of political parties may not be a one-size-fits-all solution but rather a nuanced balance that depends on the specific dynamics and priorities of each democratic society.

Explore related products

$11.99 $16.95

What You'll Learn

Impact of Multiparty Systems on Governance

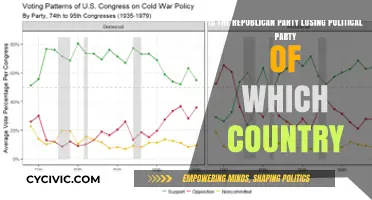

Multiparty systems inherently fragment political power, distributing it across numerous parties rather than concentrating it in a few. This fragmentation can lead to both gridlock and collaboration. In countries like Belgium or the Netherlands, where multiparty systems are the norm, coalition governments are common. These coalitions often require compromise, forcing parties to negotiate and find common ground. However, this process can be time-consuming and may result in policy stagnation if parties prioritize ideological purity over governance. For instance, Belgium once went 541 days without a formal government due to the complexity of coalition-building among its diverse parties.

Consider the practical implications of such fragmentation. In a multiparty system, smaller parties often hold disproportionate power, acting as kingmakers in coalition negotiations. This dynamic can lead to policy distortions, as minor parties push for specific agendas in exchange for their support. For example, in Israel’s multiparty system, small religious parties have historically influenced broader national policies, sometimes at the expense of secular or majority interests. Policymakers in such systems must balance inclusivity with efficiency, ensuring that governance isn’t paralyzed by the demands of too many stakeholders.

A comparative analysis reveals that multiparty systems can enhance representation but may dilute accountability. In India, the world’s largest democracy, regional parties play a crucial role in national politics, giving voice to diverse cultural and linguistic groups. However, this diversity can complicate decision-making, as seen in the slow implementation of nationwide reforms. Conversely, in Germany, the multiparty system has fostered a culture of consensus-building, with the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Social Democratic Party (SPD) often forming grand coalitions. The takeaway here is that the impact of multiparty systems on governance depends on institutional design—specifically, electoral rules and the presence of mechanisms to streamline decision-making.

To maximize the benefits of multiparty systems, consider these steps: first, adopt proportional representation with thresholds to limit the proliferation of tiny, fringe parties. Second, establish clear rules for coalition formation to reduce negotiation periods. Third, encourage cross-party collaboration through joint committees or issue-based alliances. Caution should be taken to avoid over-fragmentation, as too many parties can lead to instability. For instance, Italy’s post-war multiparty system often resulted in short-lived governments until electoral reforms in the 1990s introduced thresholds to reduce party proliferation.

Ultimately, the impact of multiparty systems on governance is context-dependent. While they foster inclusivity and representation, they require robust institutional frameworks to prevent gridlock. Policymakers must strike a balance between diversity and decisiveness, ensuring that the system serves the public interest rather than becoming a battleground for partisan interests. The solution isn’t necessarily more or fewer parties but a system designed to harness the strengths of multiparty dynamics while mitigating their risks.

Where Words Shape Politics: Analyzing Language's Power in NYTimes Coverage

You may want to see also

Role of Smaller Parties in Representation

Smaller political parties often serve as the canary in the coal mine of democratic systems, amplifying voices that larger parties overlook. In countries like Germany, where proportional representation allows smaller parties like the Greens or the Free Democratic Party (FDP) to gain parliamentary seats, these groups push niche but critical issues—climate policy, digital rights—into the mainstream. Their presence forces coalition-building, which, while sometimes messy, ensures that governance reflects a broader spectrum of public opinion rather than the polarized extremes of two-party dominance.

Consider the mechanics of representation: smaller parties act as pressure valves for societal discontent. In India, regional parties like the Trinamool Congress or the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) address hyper-local concerns—water scarcity, agrarian distress—that national parties like the BJP or Congress might gloss over. This granular focus fosters accountability, as these parties’ survival depends on delivering tangible results to their constituencies. However, their effectiveness hinges on electoral systems; in winner-takes-all models (e.g., the U.S.), such parties often face extinction, leaving voters with no outlet for their grievances.

A cautionary note: smaller parties are not inherently virtuous. In fragmented systems like Israel’s, their proliferation can lead to legislative gridlock and unstable coalitions. The 2021 Israeli election saw 13 parties enter the Knesset, yet it took months to form a government. Here, the solution isn’t fewer parties but smarter thresholds—a minimum vote share (e.g., 5%) to qualify for seats, as in Turkey or New Zealand. This balances diversity with governability, ensuring smaller parties contribute without paralyzing the system.

To maximize their role, electoral reforms are key. Mixed-member proportional systems (used in Germany and New Zealand) offer a blueprint: voters cast one vote for a local representative and another for a party, blending direct accountability with proportionality. For activists and policymakers, the takeaway is clear: advocate for systems that lower barriers to entry for smaller parties but include safeguards against fragmentation. This dual approach ensures representation remains both inclusive and functional.

Understanding Queer Politics: Identity, Resistance, and Social Transformation Explained

You may want to see also

Effectiveness of Two-Party Dominance

Two-party dominance simplifies the electoral landscape, offering voters a clear choice between distinct ideologies. In the United States, for instance, the Democratic and Republican parties have historically represented contrasting views on issues like healthcare, taxation, and social policies. This clarity can be particularly beneficial for voters who prefer straightforward decisions, as it reduces the cognitive load of navigating multiple party platforms. However, this simplicity comes at the cost of nuance, often forcing voters to compromise on certain beliefs to align with one of the two major parties.

From a governance perspective, two-party systems can foster stability by encouraging coalition-building within parties rather than across them. This internal cohesion can lead to more predictable policy outcomes, as seen in the UK’s Conservative and Labour party dynamics. Yet, this stability can also stifle innovation, as minority viewpoints within the dominant parties may be marginalized. For example, centrist or progressive ideas within a conservative party might struggle to gain traction, limiting the diversity of solutions to complex problems.

Critics argue that two-party dominance can lead to political polarization, as parties may adopt extreme positions to solidify their base. The U.S. political climate in recent decades illustrates this, with increasing partisan gridlock hindering legislative progress. In contrast, proponents suggest that such systems encourage moderation through the need to appeal to a broader electorate. For instance, the Australian Labor Party and the Liberal-National Coalition often temper their policies to attract swing voters, which can result in more centrist governance.

A practical consideration is the efficiency of two-party systems in decision-making. With fewer parties to negotiate, legislative processes can move more swiftly, as evidenced by the UK’s ability to pass Brexit-related legislation despite its contentious nature. However, this efficiency can come at the expense of inclusivity, as smaller parties representing specific demographics or regions may be excluded from the political process. For voters in such groups, the effectiveness of two-party dominance is questionable, as their interests may remain unaddressed.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of two-party dominance hinges on the specific context and priorities of a political system. While it offers clarity and stability, it risks oversimplifying complex issues and marginalizing minority voices. Policymakers and voters must weigh these trade-offs carefully, considering whether the benefits of a streamlined system outweigh the potential loss of diversity and representation. In doing so, they can better determine whether two-party dominance is a solution or a limitation in modern politics.

Uniting for Power: Understanding the Implications of Political Party Mergers

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.59 $18.99

Political Fragmentation vs. Stability

The proliferation of political parties can either invigorate democracy or paralyze it, depending on the context. In countries with deeply entrenched two-party systems, such as the United States, the introduction of additional parties can break the gridlock caused by polarized bipartisanship. For instance, third parties like the Libertarians or Greens often push mainstream parties to address issues like climate change or criminal justice reform, which might otherwise be ignored. However, in nations with already fragmented party systems, like Israel or Belgium, the addition of more parties can exacerbate instability, leading to frequent coalition collapses and governance inefficiency. The key lies in the balance: too few parties stifle diverse voices, while too many can fragment consensus.

Consider the mechanics of coalition-building in multiparty systems. In Germany, a country with a robust multiparty democracy, coalitions are formed through negotiation and compromise, often resulting in stable governments that reflect a broader spectrum of public opinion. Yet, this stability comes at a cost—smaller parties may dilute their core principles to secure power, and coalition agreements can lead to policy stagnation. Conversely, in India, the world’s largest democracy, the sheer number of regional and national parties has sometimes led to weak, short-lived governments, undermining long-term policy implementation. The takeaway? Multiparty systems thrive when institutions are strong enough to manage diversity, but falter when they lack mechanisms for consensus-building.

To navigate the trade-offs between fragmentation and stability, policymakers should focus on institutional design. Electoral systems play a critical role: proportional representation encourages party diversity but risks fragmentation, while majoritarian systems favor stability at the expense of representation. A hybrid approach, such as Germany’s mixed-member proportional system, can strike a balance. Additionally, setting a minimum vote threshold for parliamentary representation, as seen in Turkey (10%) or Israel (3.25%), can prevent excessive fragmentation without suppressing minority voices. Practical tip: when reforming electoral systems, prioritize mechanisms that incentivize cooperation, such as ranked-choice voting or coalition bonuses, to mitigate the risks of fragmentation.

A persuasive argument for reducing party proliferation centers on the need for decisive governance. In times of crisis—economic downturns, pandemics, or security threats—a fragmented political landscape can hinder swift action. For example, Italy’s frequent government collapses during the Eurozone crisis underscored the dangers of excessive fragmentation. Conversely, countries with fewer, more dominant parties, like the UK or Canada, often exhibit greater decisiveness, albeit at the risk of marginalizing opposition voices. The challenge is to preserve stability without sacrificing the inclusivity that multiparty systems offer. One solution is to strengthen the role of independent institutions, such as courts or central banks, to act as checks on majority power while ensuring minority representation.

Ultimately, the choice between more or fewer political parties is not binary but contextual. A descriptive analysis reveals that stable democracies share common traits: strong institutions, a culture of compromise, and mechanisms to manage diversity. For instance, Switzerland’s consensus-driven model, with its multiparty system and direct democracy tools, exemplifies how fragmentation can coexist with stability. Conversely, countries with weak institutions, like Lebanon, struggle to manage even moderate party diversity. The lesson? Rather than fixating on the number of parties, focus on fostering a political ecosystem that values dialogue, accountability, and inclusivity. Practical advice: encourage cross-party collaboration through joint committees, public debates, and incentives for bipartisan legislation to bridge divides and enhance stability.

The Rise of Political Bosses and Their Corrupt Practices

You may want to see also

Voter Choice and Party Proliferation

The proliferation of political parties can significantly expand voter choice, but this expansion is not inherently beneficial. In multi-party systems, voters often face a broader spectrum of ideologies and policies, which can lead to more nuanced representation. For instance, in countries like Germany or India, the presence of multiple parties allows for the articulation of diverse interests, from environmental sustainability to regional autonomy. However, this diversity can also fragment the electorate, making it harder for any single party to achieve a governing majority without coalition-building, which can slow decision-making and dilute policy coherence.

Consider the mechanics of voter behavior in such systems. When presented with numerous options, voters may feel empowered but also overwhelmed. Research suggests that beyond a certain threshold—typically around five to seven parties—voters begin to experience "choice overload," leading to indecision or reliance on superficial factors like party branding rather than policy substance. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced among younger voters (ages 18–25), who may lack the historical context to differentiate between parties with similar platforms. To mitigate this, political education initiatives could focus on teaching voters how to critically evaluate party manifestos and track records.

A comparative analysis of two-party and multi-party systems reveals trade-offs in voter choice. In the United States, the dominance of the Democratic and Republican parties simplifies decision-making but often forces voters into a binary choice that may not reflect their nuanced views. Conversely, in Israel, where over a dozen parties regularly compete, voters enjoy greater ideological alignment but face frequent elections due to coalition instability. A practical tip for voters in such systems is to prioritize parties based on core issues rather than attempting to align with every policy, as this can lead to paralysis.

The role of electoral systems cannot be overlooked in this discussion. Proportional representation systems, common in multi-party democracies, ensure that smaller parties gain seats in proportion to their vote share, thereby amplifying minority voices. However, this can also lead to the rise of fringe parties with extremist agendas, as seen in some European countries. To balance representation and stability, mixed-member proportional systems, as used in Germany, offer a compromise by combining local constituency representation with proportional allocation of seats. Voters in such systems should familiarize themselves with both components of the ballot to maximize their impact.

Ultimately, the value of party proliferation depends on the context and goals of the electorate. If the aim is to foster inclusivity and representational diversity, more parties are likely the solution. However, if efficiency and decisiveness are prioritized, fewer parties with broader coalitions may be preferable. Voters should approach this question not as a binary choice but as a spectrum, weighing the benefits of expanded choice against the costs of fragmentation. Practical steps include engaging in cross-party dialogues, supporting electoral reforms that encourage collaboration, and holding parties accountable for their promises, regardless of their size.

Understanding Political Party Ads in Washington: Strategies and Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

More political parties can increase representation and diversity of ideas, but it may also lead to fragmentation and difficulty in forming stable governments.

Fewer parties can streamline decision-making, but it risks limiting voter choice and suppressing minority voices.

More parties can better represent niche interests, but they may also create polarization and hinder consensus-building.

Fewer parties might reduce competition for resources, but it could also lead to monopolistic control and lack of accountability.

The solution often lies in improving party accountability, electoral systems, and civic engagement rather than solely focusing on the number of parties.