The effectiveness of the system of political parties is a subject of ongoing debate, as it plays a pivotal role in shaping governance, representation, and policy-making within democratic societies. While political parties serve as essential vehicles for aggregating interests, mobilizing voters, and structuring political competition, their efficacy is often questioned due to issues such as polarization, gridlock, and the prioritization of partisan interests over public welfare. Critics argue that the two-party dominance in some systems stifles diverse voices and limits policy innovation, while proponents contend that parties provide stability, accountability, and a framework for citizen engagement. Evaluating their effectiveness requires examining their ability to foster inclusive representation, address societal challenges, and maintain public trust in democratic institutions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Representation of Diverse Interests | Effective systems ensure diverse societal interests are represented. |

| Accountability | Parties hold governments accountable through opposition and checks. |

| Stability | Multi-party systems can lead to coalition governments, sometimes unstable. |

| Voter Engagement | Effective systems encourage higher voter turnout and civic participation. |

| Policy Formulation | Parties provide clear policy alternatives for voters to choose from. |

| Corruption and Transparency | Effective systems reduce corruption through transparency and oversight. |

| Inclusivity | Ensures marginalized groups are represented in the political process. |

| Adaptability | Ability to respond to changing societal needs and global challenges. |

| Polarization | Can lead to extreme polarization in two-party systems. |

| Efficiency in Decision-Making | Multi-party systems may slow decision-making due to consensus-building. |

| Public Trust | Effective systems maintain higher levels of public trust in institutions. |

| Global Comparisons | Nordic countries often rank high in party system effectiveness. |

| Role of Media | Media plays a critical role in holding parties accountable. |

| Funding and Resources | Fair funding ensures smaller parties can compete effectively. |

| Electoral Systems | Proportional representation often leads to more inclusive outcomes. |

Explore related products

$17.49 $26

$28.31 $42

What You'll Learn

- Party Polarization Impact: How extreme party divisions affect governance and policy-making effectiveness

- Voter Representation: Do parties truly reflect the diverse interests and needs of voters

- Two-Party Dominance: Does a two-party system limit political diversity and innovation

- Campaign Financing: How does money influence party agendas and electoral outcomes

- Accountability Mechanisms: Are parties held accountable for their promises and actions

Party Polarization Impact: How extreme party divisions affect governance and policy-making effectiveness

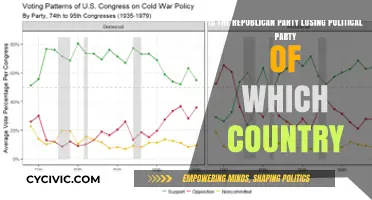

Extreme party polarization has become a defining feature of modern political landscapes, particularly in systems like the United States, where ideological divides between major parties have widened dramatically. This polarization manifests in rigid adherence to party lines, reduced cross-aisle collaboration, and a focus on winning partisan battles over solving collective problems. The result? A governance system that struggles to respond effectively to crises, from economic downturns to public health emergencies. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, polarized responses to mask mandates and vaccine distribution highlighted how party divisions can hinder unified, science-driven policy implementation, exacerbating public confusion and prolonging recovery efforts.

To understand the mechanics of this dysfunction, consider the legislative process. Polarization often leads to gridlock, as parties prioritize blocking the opposition’s agenda over advancing their own. Filibusters, veto threats, and procedural delays become weapons in a partisan arms race, stalling even widely supported measures. For example, infrastructure bills, which historically enjoyed bipartisan backing, now face protracted battles as parties seek to deny the other a political win. This gridlock isn’t just procedural—it’s psychological. Lawmakers increasingly view compromise as betrayal, fearing backlash from ideologically extreme bases that dominate primary elections.

The impact on policy-making effectiveness is profound. Polarization encourages short-term, symbolic victories over long-term solutions. Policies are crafted to appeal to narrow constituencies rather than address broad societal needs. Take climate change: despite overwhelming scientific consensus, partisan divides have prevented comprehensive legislation, with one party often dismissing the issue entirely. This short-sightedness undermines trust in government, as citizens witness their leaders prioritizing party loyalty over problem-solving. Over time, this erodes democratic legitimacy, as voters perceive the system as incapable of delivering meaningful results.

Breaking this cycle requires structural and cultural shifts. One practical step is reforming primary election systems to reduce the influence of extreme factions. Open primaries or ranked-choice voting could incentivize candidates to appeal to a broader electorate. Additionally, institutional changes like eliminating the filibuster or creating bipartisan committees for critical issues could foster collaboration. However, these solutions face resistance from those who benefit from the status quo. Ultimately, addressing polarization demands a reorientation of political incentives—away from partisan warfare and toward governance that serves the common good. Without such changes, the effectiveness of party-based systems will continue to decline, leaving societies ill-equipped to tackle their most pressing challenges.

My Political Stance: Navigating Key Issues Shaping Our Future

You may want to see also

Voter Representation: Do parties truly reflect the diverse interests and needs of voters?

Political parties are often seen as the backbone of democratic systems, but their effectiveness in representing the diverse interests and needs of voters is increasingly under scrutiny. A key issue lies in the tendency of parties to prioritize broad, unifying platforms over niche concerns. For instance, while major parties may address economic growth or healthcare, they often overlook specific issues like rural broadband access or cultural preservation, which are critical to smaller demographics. This gap in representation can leave certain voter groups feeling marginalized, questioning whether their voices are truly heard in the political process.

To bridge this divide, some argue that parties should adopt more flexible structures, such as allowing for internal factions or caucuses that champion specific causes. For example, the Labour Party in the UK has various affiliated groups, like the Fabian Society, which push for progressive policies within the broader party framework. Similarly, proportional representation systems, as seen in countries like Germany or New Zealand, enable smaller parties to gain seats, ensuring that diverse interests are not drowned out by majority rule. However, this approach is not without challenges, as it can lead to coalition governments that struggle to implement cohesive policies.

Another critical factor is the role of primaries and candidate selection processes. In the U.S., for instance, primary elections often favor candidates who appeal to the most extreme wings of their party, rather than those who represent the median voter. This dynamic can result in elected officials who are out of step with the broader electorate, further exacerbating the representation gap. To counter this, some propose open primaries or ranked-choice voting, which encourage candidates to appeal to a wider spectrum of voters and reduce polarization.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of political parties in representing voters hinges on their willingness to evolve. Parties must actively seek input from underrepresented groups, leverage data to understand granular needs, and embrace innovative mechanisms for inclusivity. For voters, staying engaged beyond election cycles—through advocacy, participation in local politics, and holding representatives accountable—is essential. While no system is perfect, a combination of structural reforms and civic participation can help ensure that parties better reflect the rich tapestry of voter interests and needs.

Understanding the Politics of Consensus: A Historical Overview and Impact

You may want to see also

Two-Party Dominance: Does a two-party system limit political diversity and innovation?

Two-party systems, exemplified by the United States' Democratic and Republican parties, often stifle political diversity by funneling discourse into a binary framework. This structure marginalizes smaller parties, such as the Green Party or Libertarians, which struggle to gain traction due to electoral mechanics like winner-take-all systems and media focus on major candidates. For instance, third-party candidates rarely surpass 5% of the national vote, despite polling showing significant public interest in alternatives. This dynamic limits the spectrum of ideas presented to voters, reducing politics to a choice between two dominant ideologies rather than fostering a marketplace of diverse solutions.

Consider the practical implications of this limitation. In a two-party system, policies often become polarized, with each party advocating for extreme versions of their platform to solidify their base. This polarization discourages innovation, as compromise and cross-party collaboration are viewed as weaknesses rather than strengths. For example, the U.S. healthcare debate has been dominated by the Affordable Care Act and calls for its repeal, with little room for hybrid models or incremental reforms that might emerge in a multi-party system. Such rigidity can hinder progress on complex issues, leaving voters with limited options that fail to address nuanced concerns.

To illustrate, examine the 2020 U.S. presidential election, where both major parties focused on mobilizing their bases rather than appealing to independents or moderates. This strategy reinforces ideological silos, making it difficult for new ideas to gain traction. In contrast, countries like Germany, with a multi-party system, often form coalition governments that blend diverse perspectives, leading to more innovative and inclusive policies. For instance, Germany’s energy transition (Energiewende) emerged from cross-party collaboration, a feat unlikely in a two-party system where such cooperation is politically risky.

Breaking the cycle of two-party dominance requires structural reforms. Ranked-choice voting, already implemented in cities like New York, allows voters to rank candidates, giving smaller parties a fairer chance. Proportional representation, used in many European countries, allocates seats based on vote share, encouraging party diversity. Advocates should push for these changes at local and state levels, as incremental reforms can build momentum for broader adoption. For example, Maine’s adoption of ranked-choice voting in federal elections demonstrates how small-scale experiments can challenge entrenched systems.

Ultimately, while two-party systems provide stability and simplicity, they come at the cost of political diversity and innovation. Voters seeking alternatives often feel disenfranchised, and policymakers are constrained by partisan loyalties. By embracing electoral reforms and demanding more inclusive structures, societies can unlock a wider range of ideas and solutions. The question is not whether two-party systems work, but whether they work well enough for the complexities of modern governance.

Sports and Politics: Unraveling the Inextricable Link Between Games and Power

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Campaign Financing: How does money influence party agendas and electoral outcomes?

Money in politics is a double-edged sword, shaping both the messages parties promote and the candidates who ultimately win. Consider the 2020 U.S. presidential election, where over $14 billion was spent, making it the most expensive in history. This staggering figure wasn’t just about buying airtime; it was about crafting narratives, mobilizing voters, and securing strategic advantages. Wealthy donors and corporations often funnel funds to candidates whose policies align with their interests, effectively tilting the scales in favor of agendas that may not reflect the broader public’s priorities. For instance, candidates backed by fossil fuel industries are less likely to champion aggressive climate policies, even if such measures are widely supported by voters.

The influence of money on party agendas is both subtle and profound. Parties often tailor their platforms to attract high-dollar donors, sometimes at the expense of grassroots issues. Take healthcare reform: while single-payer systems enjoy significant public support in many countries, they rarely gain traction in campaign promises because they threaten the profits of powerful healthcare and insurance industries. This dynamic creates a feedback loop where policies are shaped not by voter needs but by the financial interests of a select few. As a result, parties may adopt watered-down versions of popular policies or avoid contentious issues altogether, undermining their effectiveness as representatives of the electorate.

Electoral outcomes are equally skewed by campaign financing. Candidates with deeper pockets can afford sophisticated advertising campaigns, extensive ground operations, and data-driven voter targeting. In contrast, underfunded candidates, often those with more progressive or populist agendas, struggle to gain visibility. This disparity was evident in the 2018 U.S. midterm elections, where 94% of House races were won by the candidate who spent the most. While money doesn’t guarantee victory, it significantly increases the odds, creating a system where wealth often translates to political power.

To mitigate these effects, some countries have implemented campaign finance reforms. Public financing models, as seen in Germany and Canada, provide candidates with state funds based on their electoral performance, reducing reliance on private donors. Contribution limits and transparency requirements, such as those in the U.S.’s McCain-Feingold Act, aim to curb the influence of big money. However, loopholes and legal challenges often dilute these efforts. For instance, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling allowed unlimited corporate spending on political campaigns, further entrenching the role of money in politics.

The takeaway is clear: campaign financing is a critical determinant of both party agendas and electoral outcomes. Without robust reforms, the system risks becoming a playground for the wealthy, sidelining the voices of ordinary citizens. Voters must demand greater transparency and accountability, while policymakers should explore innovative solutions like crowdfunding or blockchain-based donation tracking to level the playing field. Only then can political parties truly serve as effective vehicles for democratic representation.

Changing Political Party Affiliation in Georgia: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Accountability Mechanisms: Are parties held accountable for their promises and actions?

The effectiveness of political parties hinges on their accountability, yet the mechanisms designed to ensure this are often flawed. Elections, the primary accountability tool, are infrequent and binary, offering voters a limited choice between parties rather than a direct evaluation of performance. This system can lead to a "lesser of two evils" scenario, where parties face minimal consequences for broken promises or poor governance as long as the alternative is perceived as worse. For instance, in the United States, the two-party dominance often shields incumbents from meaningful accountability, as voters lack viable alternatives.

To enhance accountability, some democracies have introduced recall elections and referendums, allowing citizens to directly challenge politicians or policies. In Switzerland, for example, citizens can initiate a referendum to overturn a law, providing a continuous check on government actions. Similarly, California’s recall process enables voters to remove elected officials mid-term, as seen in the 2003 recall of Governor Gray Davis. However, these mechanisms are resource-intensive and rarely used, limiting their effectiveness as a widespread accountability tool.

Another layer of accountability comes from independent institutions like anti-corruption bodies and audit agencies. South Africa’s Public Protector, for instance, investigates government misconduct and can recommend corrective actions. Yet, such institutions are only as strong as their enforcement powers and political independence. In countries with weak rule of law, these bodies often face political interference, rendering them ineffective. For example, despite the Public Protector’s findings against former President Jacob Zuma, years of legal battles and political obstruction delayed accountability.

Media and civil society play a critical role in holding parties accountable by scrutinizing their actions and amplifying public dissent. Investigative journalism, such as the *Panama Papers* exposé, has uncovered corruption and forced political resignations. However, media effectiveness depends on press freedom and public trust. In polarized societies, media outlets often align with political factions, undermining their role as neutral watchdogs. Similarly, civil society’s impact varies; while protests in Hong Kong pressured the government, they also faced harsh crackdowns, highlighting the risks of activism in authoritarian contexts.

Ultimately, accountability mechanisms are only as effective as the political will to enforce them. While elections, direct democracy tools, independent institutions, and media scrutiny provide frameworks, their success relies on robust implementation and public engagement. Strengthening these mechanisms requires reforms such as more frequent elections, empowering anti-corruption bodies, and protecting press freedom. Without such measures, parties will continue to evade accountability, eroding public trust in the political system.

Where Does Reuters Lean Politically? Uncovering Its Editorial Stance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The effectiveness of political parties in representing diverse views depends on the system in place. In pluralistic democracies, parties often adapt to reflect various ideologies, but in two-party systems, representation can be limited. However, no system perfectly captures all perspectives, leading to gaps in representation.

Political party systems can foster both cooperation and polarization. While parties often collaborate to form governments in multiparty systems, they can also deepen divisions by prioritizing partisan interests over national unity, especially in highly polarized environments.

Political parties can hold leaders accountable through internal mechanisms, opposition scrutiny, and electoral competition. However, this effectiveness diminishes when parties prioritize loyalty over accountability or when corruption and lack of transparency prevail.

The party system can facilitate efficient governance by providing clear majorities and policy direction. However, it can also lead to gridlock, especially in fragmented systems or when parties prioritize ideological purity over practical solutions. Efficiency depends on the balance of power and the willingness to compromise.