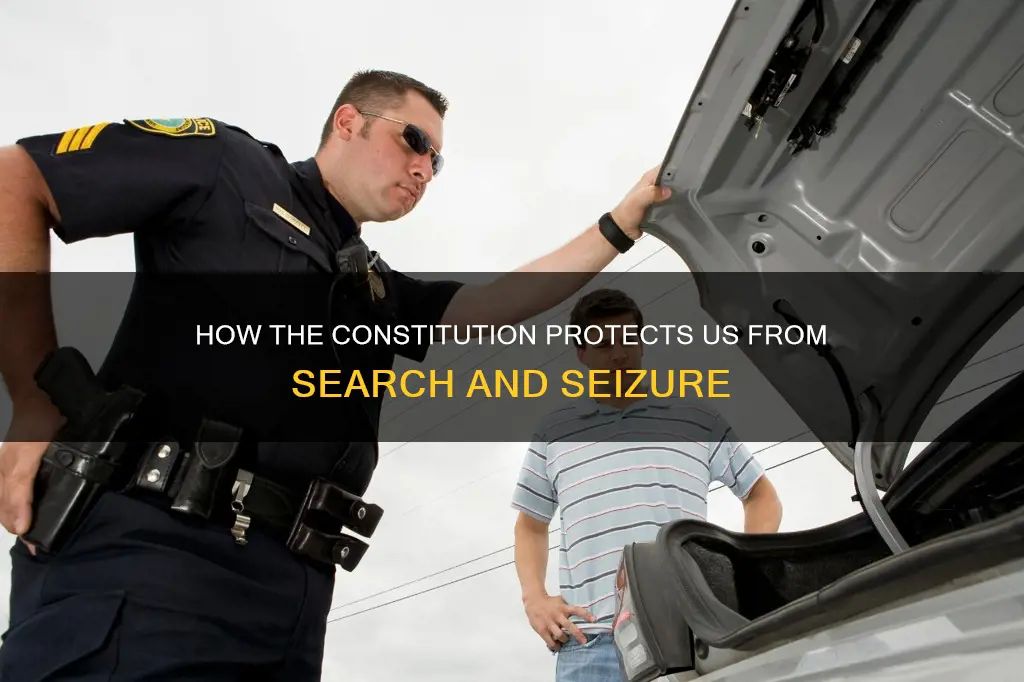

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution is a crucial safeguard against unreasonable searches and seizures, protecting the rights of individuals to privacy, personal security, and private property. This amendment, part of the Bill of Rights, was introduced in 1789 by James Madison to prevent arbitrary invasions by government officials and ensure that searches and arrests are conducted with judicial oversight. It requires warrants to be issued by a judge or magistrate, based on probable cause, and with specific descriptions of the places to be searched and items to be seized. While there are exceptions to the warrant requirement, such as consent searches and vehicle searches, the Fourth Amendment generally ensures that evidence obtained through unlawful means is inadmissible in criminal trials. This amendment reflects the Framers' intent to prevent the unjust searches and seizures they experienced under English rule, where general warrants were abused by the Crown.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose | To protect people from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government |

| Requirements for issuing warrants | Warrants must be issued by a judge or magistrate, justified by probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and must particularly describe the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized |

| Exceptions to warrants | Consent searches, motor vehicle searches, evidence in plain view, exigent circumstances, border searches, and other situations |

| Enforcement | The exclusionary rule holds that evidence obtained as a result of a Fourth Amendment violation is generally inadmissible at criminal trials |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

The Fourth Amendment

The exclusionary rule is one way the Fourth Amendment is enforced. This rule states that evidence obtained as a result of a Fourth Amendment violation is generally inadmissible at criminal trials. Evidence discovered as an indirect result of an illegal search may also be inadmissible as "fruit of the poisonous tree", unless it inevitably would have been discovered by legal means.

What Does the Declaration of Independence Preamble Indicate?

You may want to see also

Requirements for warrants

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures and outlines the requirements for issuing warrants. Search warrants are usually a prerequisite for searches, protecting individuals' reasonable expectations of privacy against unreasonable government intrusion.

Warrants must be issued by a judge or magistrate and justified by probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation. They must also specifically describe the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized. The Fourth Amendment's "general touchstone of reasonableness" governs the method of executing the warrant.

The Fourth Amendment's origins lie in British law and the events of the American colonial period. It was influenced by the Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776), which explicitly forbade the use of general warrants, and the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights (1780), which stated that all searches must be "reasonable". By 1784, eight state constitutions included provisions against general warrants.

While warrants are typically required for searches, there are exceptions. For example, administrative searches such as vehicle checkpoints, factory searches, and detention of a traveler do not always require warrants. Additionally, if officers have a reasonable suspicion that a crime is occurring, they can stop and frisk a suspect for weapons to ensure their safety without a warrant.

The Supreme Court has also created exceptions to the warrant requirement, including good faith of police officers, searches incident to valid arrests, automobile searches, and evidence in plain view. However, the Court has also narrowed privacy rights in some cases, such as in Carpenter v. United States, where it ruled that the government violated Mr. Carpenter's reasonable expectation of privacy by acquiring private information without a warrant.

David Brearley: A Founding Father and Constitution Writer

You may want to see also

Probable cause

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures. It requires a judicially sanctioned warrant, which must be issued by a judge or magistrate, justified by probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and must particularly describe the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.

Florida's Constitution Revision Commission: How Independent?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Exceptions to the Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures without a warrant. However, there are several exceptions to this rule, which have been outlined by the Supreme Court.

Plain View Exception

Officers may seize items that are in plain view, as long as they have a right to be in that position. For example, if an officer stops someone for speeding and sees what appears to be drugs in the back seat of the car, they can seize the suspected drugs without a warrant.

Consent

A warrantless search may be lawful if an officer has asked for and received consent to search. This consent can also be given by a co-occupant of a shared property, as seen in the case of United States v. Matlock.

Search Incident to Lawful Arrest

When a law enforcement officer makes a lawful arrest, they may search both the person arrested and the area within the person's immediate control. This is justified by the need to ensure officer safety and preserve evidence.

Probable Cause and Exigent Circumstances

A warrantless search may be justified if there is probable cause to search and exigent circumstances, such as imminent danger, imminent escape, or the destruction of evidence.

Terry Stop

In Terry v. Ohio, the Supreme Court clarified that police officers can stop and frisk a person for weapons if they have a reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. This type of investigative stop is known as a Terry stop.

Automobile Exception

Officers may search any area of a vehicle if they have probable cause to believe it contains evidence of a criminal activity.

Emergency and Public Safety

Warrantless searches may be permitted in emergencies and situations involving public safety concerns.

Iroquois Constitution's Influence on the Declaration of Independence

You may want to see also

Supreme Court cases

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures. Generally, evidence found through an unlawful search cannot be used in a criminal proceeding. The Fourth Amendment typically requires "a neutral and detached authority interposed between the police and the public", and it is offended by "general warrants" and laws that allow searches to be conducted indiscriminately and without regard to their connection with [a] crime under investigation.

Katz v. United States (1967)

This case is considered a leading case on Fourth Amendment searches. Law enforcement agents installed a recording device in a public telephone booth without obtaining a warrant to learn about a suspect's illegal gambling activity. The Supreme Court ruled that installing the wiretap constituted a search under the Fourth Amendment.

Riley v. California (2014)

The Supreme Court ruled that without a warrant, the police generally may not search digital information on a cell phone seized from an individual who has been arrested.

Winston v. Lee (1985)

The ruling stated that a police officer may not seize an unarmed, non-dangerous suspect by shooting them dead. However, when an officer has probable cause to believe that a suspect poses a threat of serious physical harm, it is not constitutionally unreasonable to prevent escape by using deadly force.

California v. Acevedo (1991)

The Supreme Court ruled that there is no per se rule that every encounter on a bus is a seizure. The test is whether a reasonable passenger would feel free to decline the officers' requests or terminate the encounter.

Florida v. Jimeno (1991)

In a search extending only to a container within a vehicle, the police may search the container without a warrant when they have probable cause to believe that it holds contraband or evidence.

Arizona v. Gant (2009)

An officer may lawfully search any area of the vehicle in which the evidence might be found when there is probable cause to believe that a vehicle contains evidence of criminal activity.

Minnesota v. Carter (1998)

The extent to which an individual is protected by the Fourth Amendment depends, in part, on the location of the search or seizure. Searches and seizures inside a home without a warrant are presumptively unreasonable.

Who's the Principal? Acting Officials and the Constitution

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution is part of the Bill of Rights. It prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures.

An unreasonable search or seizure is one that is conducted without a warrant or probable cause. The Fourth Amendment requires the government to obtain a warrant based on probable cause to conduct a legal search and seizure.

A warrant is a document issued by a judge or magistrate that authorises a search or seizure. Warrants must be justified by probable cause and must describe the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized. A warrant is needed for most search and seizure activities, but there are exceptions for consent searches, motor vehicle searches, evidence in plain view, exigent circumstances, and border searches, among others.

Evidence obtained as a result of a Fourth Amendment violation is generally inadmissible at criminal trials. This is known as the exclusionary rule, which was established in Weeks v. United States (1914).

![New York Search & Seizure 2025 Edition [LATEST EDITION]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41O2vzeA7rL._AC_UY218_.jpg)