Marriage is not mentioned in the US Constitution, and therefore, it is not a power delegated to the federal government to regulate. The Constitution provides no citizen of any gender or orientation a constitutional right to marriage. However, in 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that denying the right of marriage to same-sex couples was unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause. This ruling, known as Obergefell v. Hodges, marked a significant shift in the legal recognition of same-sex marriages.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does the Constitution provide citizens with a right to marriage? | No, the Constitution does not provide citizens of any gender or orientation with a right to marriage. |

| Is marriage mentioned in the Constitution? | No, marriage is not mentioned in the Constitution. |

| Can the federal government regulate marriage? | No, as the Constitution does not mention marriage, it is not a power delegated to the federal government to regulate. |

| Can states regulate marriage? | Yes, each state is free to set the conditions for a valid marriage, subject to limits set by the state's own constitution and the U.S. Constitution. |

| Can the Supreme Court create a Constitutional right to marriage? | No, for the Supreme Court to create a Constitutional right to marriage, it would have to violate the 10th Amendment, which states that "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." |

| Has the Supreme Court ruled on same-sex marriage? | Yes, in its 2015 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that denying the right of marriage to same-sex couples was unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Marriage is not mentioned in the Constitution

The Constitution makes no mention of marriage, and therefore, it is not a power delegated to the federal government to regulate. The Constitution is an elegant document that is rigid in its respect for federalism. Its framework of powers is encased in a document designed to require overwhelming support for any changes to be made.

The 10th Amendment states: "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." This means that the people and the states have Constitutional rights. All rights that have not been delegated to the federal government are retained by the people, including the right to determine whom, if anyone, should be given the right to marry and the benefits and burdens that come with it.

The Supreme Court cannot create a Constitutional right to marriage without first violating the rights of the people under the 10th Amendment. One principle of statutory interpretation is to not read into a law words that are not there. The words "marriage" and "gay marriage" do not exist in the Constitution, and therefore, their meaning need not be considered.

The Federal Marriage Amendment (FMA), also referred to as the Marriage Protection Amendment, was a proposed amendment to the Constitution that would have legally defined marriage as a union between one man and one woman. The FMA would also have prevented the extension of marriage rights to same-sex couples. However, the last congressional vote on the proposed amendment occurred in the House of Representatives on July 18, 2006, and the motion failed to pass.

The Declaration of Independence: Precursor to the Constitution?

You may want to see also

The Supreme Court's role in same-sex marriage

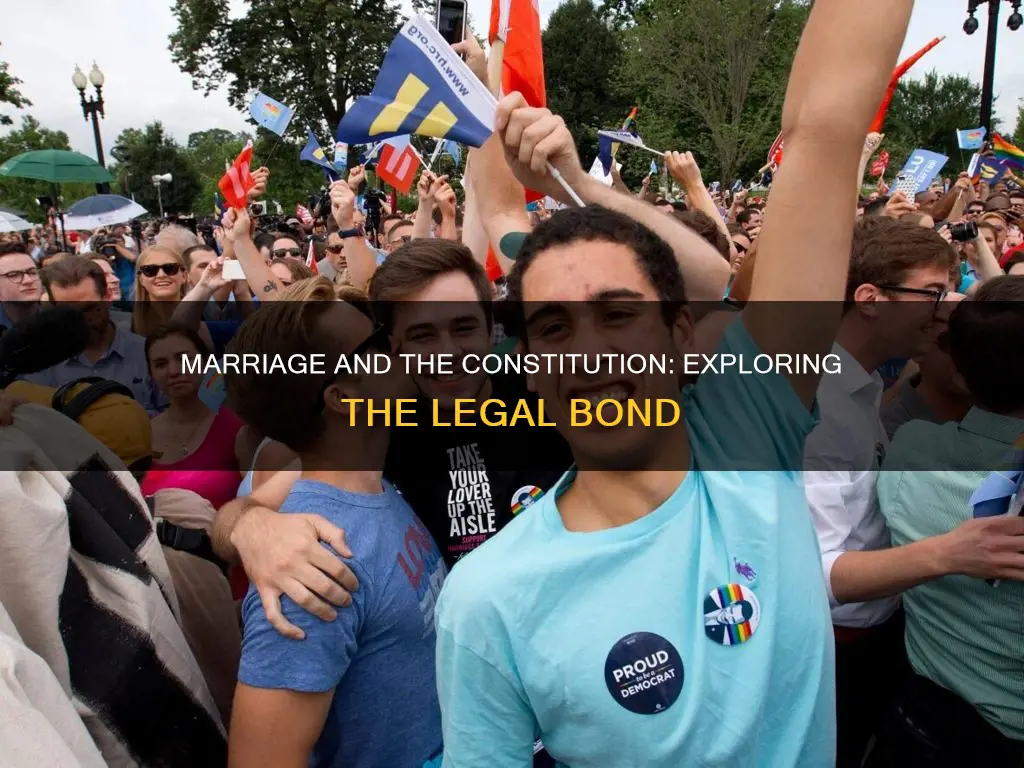

The Supreme Court has played a significant role in shaping the legal landscape for same-sex marriage in the United States. While the expansion of marriage rights to same-sex couples has been a gradual process, the Supreme Court's rulings have been pivotal in this evolution.

In 1972, the Supreme Court of the United States declined to get involved in the case of Baker v. Nelson, which sought to challenge marriage laws that discriminated based on sex. This marked an early missed opportunity for the Court to address the issue. However, in 1996, the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) was passed, explicitly defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman, which further solidified the exclusion of same-sex couples from marriage rights.

The tide began to turn in 2003 when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health that it was unconstitutional for the state to abridge marriage based on sex. This decision sparked a wave of state-level court rulings, legislation, and direct popular votes that gradually expanded marriage rights to same-sex couples across the country. By 2015, same-sex marriage was legally recognized in 36 states.

The Supreme Court of the United States finally addressed the issue directly in two landmark cases. In 2013, the Court struck down a key provision of DOMA in United States v. Windsor, ruling that it violated the Fifth Amendment and led to federal recognition of same-sex marriage. This decision extended federal benefits to married same-sex couples, marking a significant victory for marriage equality.

Two years later, in 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that the fundamental right of same-sex couples to marry is guaranteed by the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This decision established same-sex marriage as a national right, ensuring that all states must recognize and honor these marriages.

Despite these landmark rulings, same-sex marriage continues to face opposition and legal challenges. In recent years, there have been efforts by conservative lawmakers to urge the Supreme Court to reconsider and overturn its decision in Obergefell. These attempts have been fueled by concerns that the Court's conservative majority, solidified during President Donald Trump's second term, may be more receptive to undoing precedent. While these resolutions carry no legal authority, they signal a persistent effort to undermine marriage equality and LGBTQ+ rights more broadly.

Congressional Committees: Constitutional or Not?

You may want to see also

Federal Marriage Amendment

The Federal Marriage Amendment (FMA), also referred to as the Marriage Protection Amendment, was a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution. The bill aimed to legally define marriage as a union of one man and one woman, and to prevent judicial extension of marriage rights to same-sex couples.

The FMA was introduced in the United States Congress on multiple occasions: in 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2008, 2013, and 2015. The original proposed Federal Marriage Amendment was written by the Alliance for Marriage under Matthew Daniels, with the assistance of legal professionals, including former Solicitor General and failed Supreme Court nominee Judge Robert Bork, and law and Princeton University professors Robert P. George and Gerard V. Bradley. It was introduced in the 107th United States Congress in the House of Representatives on May 15, 2002, by Representative Ronnie Shows (D-Miss.), with 22 cosponsors. The bill was designated H.J.Res 93 and was immediately referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary.

The last congressional vote on the proposed amendment occurred in the House of Representatives on July 18, 2006, when the motion failed 236 to 187, falling short of the 290 votes required for passage. The Senate has only voted on cloture motions with regard to the proposed amendment, the last of which was on June 7, 2006, when the motion failed 49-48, falling short of the 60 votes required to allow the Senate to proceed with the proposal.

Although the FMA was never passed, prior to the Supreme Court's ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges on June 26, 2015, thirty states passed state constitutional amendments defining marriage as being between one man and one woman. These amendments were invalidated by the ruling, which held that the government could not refuse to recognize same-sex marriage.

Emoluments Clause: A Constitutional Conundrum?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.5 $18.99

The Constitution and marriage rights for inmates

The Constitution of the United States grants its citizens the right to marry, and this right extends to prisoners. In 1981, a lawsuit was filed in Missouri challenging the restrictions on inmate mail, marriage, and visitation. This case, known as Turner v. Safley, established that inmates have a fundamental right to marry, and that this right is not extinguished by incarceration. The Supreme Court ruled that marriage is "one of the 'basic civil rights of man,' fundamental to our very existence and survival". This decision set a precedent for future cases, now known as the "Turner Test", which states that a prison regulation is constitutional if it satisfies four factors: a rational connection to a legitimate government interest, the existence of alternative means for prisoners to exercise their rights, the impact on resources and staff, and the existence of alternatives to the regulation.

However, it is important to note that while inmates have the right to marry, this does not include the right to conduct a wedding according to their exact wishes. Jail staff are not expected to be wedding planners, and there may be legitimate security concerns or institutional interests that require placing reasonable restrictions on an inmate's marriage. For example, some states have specific laws regarding proxy marriages that must be considered. Additionally, if a marriage application is denied, inmates should be afforded the opportunity to file a grievance and challenge the decision.

The Supreme Court's decision on gay marriage has also had implications for inmate marriage policies. Policies should be updated to be gender-neutral, and homosexual marriage applications should be treated with the same consideration as any other marriage application. Failure to adhere to these updated policies may result in potential litigation from inmates.

In conclusion, the Constitution grants inmates the right to marry, and this right is protected by the Supreme Court's decision in Turner v. Safley. However, this right is not absolute, and reasonable restrictions may be placed to address security concerns or institutional interests. Inmates whose marriage applications are denied have the right to file a grievance and challenge the decision.

Exploring Virginia's Constitution: Understanding the Comprehensive Civics SOLPASS

You may want to see also

State recognition of out-of-state marriages

Marriage in the United States is a matter of state law. Each state has its own requirements for marriage, and the only federal law about marriage is that a marriage valid in one state is valid in every other state. This is known as the "'place of celebration' rule", which means that a marriage that is valid where celebrated is valid everywhere.

The "place of celebration" rule is not absolute, and there are two historical exceptions. States can refuse recognition of an out-of-state marriage if it violates "natural law" or the state's "positive law". Under the "natural law" exception, courts tend to refuse recognition to marriages that are considered universally abhorrent, such as polygamous or incestuous marriages. The "positive law" exception allows states to continue to prohibit a particular kind of marriage, despite sometimes recognizing one formed out of state. For example, some states have refused to recognize same-sex marriages performed out of state, even when their own laws would prohibit and invalidate such marriages if they had been performed in their own state.

In the case of Baker v. State of Vermont, the state supreme court ordered its legislature to "extend to same-sex couples the common benefits and protections that flow from marriage under Vermont law". The court allowed the legislature to create an "equivalent statutory alternative", which resulted in civil unions. However, these civil unions are denied equal treatment under the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) and raise "portability" questions outside of Vermont.

When it comes to common-law marriages, only a handful of states recognize them, including Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah. California does not recognize common-law marriage within its borders but does acknowledge that they are legally established in other states. This recognition is important for couples moving to California who have established their marital status under common law in another state.

Overall, the recognition of out-of-state marriages in the United States is a complex issue that involves state laws, court rulings, and federal laws. While the "place of celebration" rule generally applies, there are exceptions and variations that depend on the specific circumstances and the laws of each state.

Executive Branch: Understanding Its Major Components

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, the Constitution does not provide citizens of any gender or orientation a constitutional right to marriage. The Constitution does not mention marriage and, therefore, it is not a power delegated to the federal government to regulate.

The FMA was a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution that would have legally defined marriage as a union of one man and one woman. The FMA would also have prevented the extension of marriage rights to same-sex couples. The last congressional vote on the proposed amendment occurred in the House of Representatives on July 18, 2006, when the motion failed 236 to 187, falling short of the 290 votes required for passage.

The Constitution does not explicitly protect the right to marry for any citizen, regardless of their background or orientation. However, in 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that denying the right of marriage to same-sex couples was unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause.