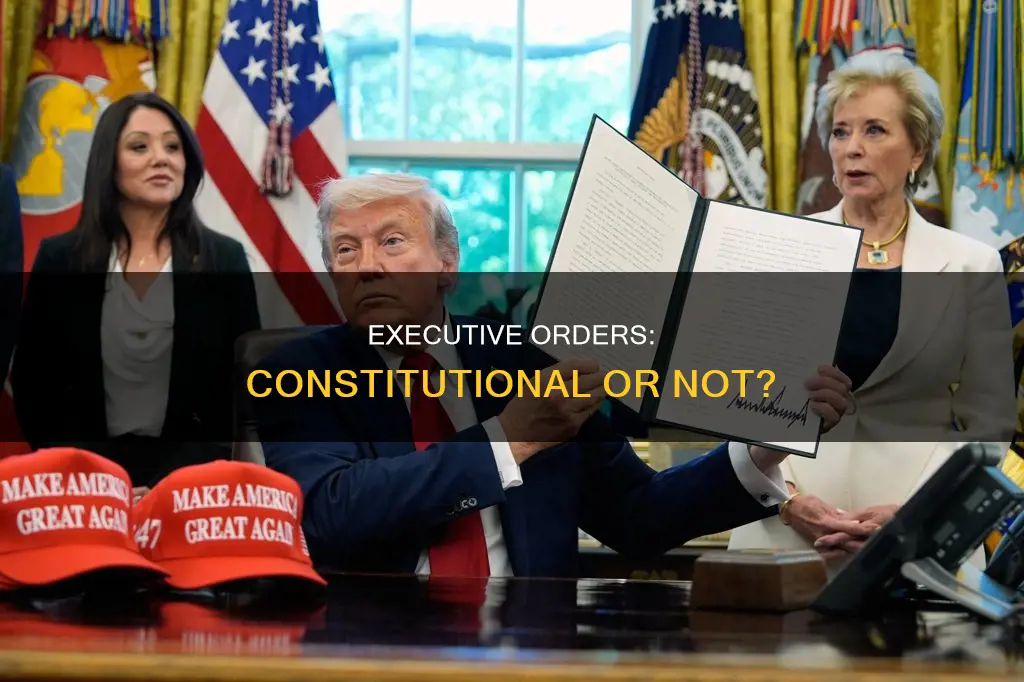

Executive orders are written, signed directives from the President of the United States that manage operations of the federal government. They are not explicitly defined in the Constitution, but derive their authority from Article II, which vests executive powers in the President, making them the commander in chief, and requiring that the President shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed. While executive orders can have the same effect as federal laws, they are not legislation and do not require approval from Congress. They can be invalidated by a federal court if they are found to be unlawful or unconstitutional. This has happened several times, including in 1952, when the Supreme Court invalidated President Truman's executive order putting steel mills under federal control during a strike.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government |

| Constitutional Basis | Article II of the US Constitution, or enacted by Congress in statutes |

| Authority | Must derive from an already existing statute or a constitutionally enumerated presidential power |

| Issuance | Requires no approval from Congress |

| Checks and Balances | Congress can enact a law that reverses the order, a court can hold that an order is unlawful, or a future president can issue a new order that rescinds or amends the previous one |

| Revocation | A president may revoke, modify, or make exceptions from any executive order |

| Validity | An executive order can be invalidated if the president lacked the authority to issue it or because its substance violates the Constitution |

| Numbering | Executive orders are numbered consecutively and can be referenced by their assigned number |

| Publication | All executive orders are published in the Federal Register, the daily journal of the federal government |

| Signature | Signed by the issuing president, followed by a "White House" notation and the date the order was issued |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Executive orders are not legislation

Executive orders are directives issued by the President of the United States to manage the operations of the federal government. They are numbered consecutively and are signed, written, and published. Executive orders do not require approval from Congress, and every American president has issued at least one. However, they are not the same as legislation.

Firstly, executive orders are not explicitly defined in the Constitution and do not have a specific provision authorizing their issuance. The Constitution does not address executive orders, and no statute grants the President the general power to issue them. Instead, the authority to issue executive orders is derived from the President's broad powers to issue directives, as well as powers granted by Congress. These powers are outlined in Article II of the Constitution, which vests the President with executive power and requires them to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed".

Secondly, executive orders cannot override federal laws and statutes. They must be rooted in Article II of the Constitution or enacted by Congress in statutes. If an executive order attempts to create an obligation, right, or penalty outside the scope of an existing statute or presidential power, it would violate the Separation of Powers doctrine and be deemed unlawful and unconstitutional. This is because it would encroach on Congress's authority to make laws.

Thirdly, there are checks and balances in place to prevent the President from misusing executive orders. Congress can enact a law that reverses an executive order, provided they have the constitutional authority to legislate on the issue. The courts can also hold an executive order unlawful if it violates the Constitution or a federal statute. Additionally, a future President can issue a new executive order that rescinds or amends a previous one.

Finally, while an executive order can have the same effect as a federal law under certain circumstances, it is not the same as legislation. Executive orders are subject to judicial review and may be overturned if they lack support by statute or the Constitution. They can be invalidated if the President lacked the authority to issue them or if their substance violates the Constitution.

The Constitution's Religious Freedom Clause

You may want to see also

The President's authority

Executive orders are written, signed directives issued by the President to manage the operations of the federal government. They are not legislation and do not require approval from Congress. However, they must be rooted in either Article II of the Constitution or enacted by Congress in statutes. The authority for an executive order must derive from an existing statute or a constitutionally enumerated presidential power. For example, an executive order that creates an obligation, right, or penalty outside the scope of existing laws or powers would violate the Separation of Powers doctrine and be deemed unlawful.

The President's executive orders can be challenged and invalidated if they are found to violate the Constitution or federal law. This can occur through a lawsuit by an aggrieved party or a ruling by the Supreme Court, as seen in the case of Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, where President Truman's executive order was invalidated as it attempted to make law rather than clarify or further existing law.

While the President has broad discretionary power to issue executive orders, there are checks and balances in place to prevent overreach. Congress can pass a new law to override an executive order, and the courts can hold an order unlawful if it violates the Constitution or federal statutes. Additionally, a future president can issue a new executive order that rescinds or amends a previous one.

In summary, the President's authority to issue executive orders stems from the US Constitution and congressional laws. These orders allow the President to direct the federal government's operations, but they are subject to checks and balances from other branches of government to ensure they do not exceed the President's constitutional powers.

Ottoman Empire's Constitutionalism: A Historical Governor's Analysis

You may want to see also

The role of the judiciary

While executive orders are not explicitly defined in the US Constitution, they are a powerful tool for the president, with the same power as federal law. The US Constitution has a set of checks and balances to ensure that no one branch of the government is more powerful than the others. The judiciary is one of these checks.

Article III of the US Constitution gives the judiciary the power to review "all cases, in law and equity, arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties". This means that the judiciary decides whether executive actions, such as executive orders, are lawful and constitutional.

Executive orders must be rooted in Article II of the US Constitution or enacted by Congress in statutes. The authority for an executive order must derive from an existing statute or a constitutionally enumerated presidential power. If an executive order is not supported by the Constitution, it can be deemed unlawful and unconstitutional.

If an executive order is deemed unlawful, it is invalidated. For this to happen, an aggrieved party must challenge the order in federal court. The Supreme Court has held that all executive orders from the president must be supported by the Constitution, and it has struck down executive orders that it deemed to be unlawful.

In conclusion, the judiciary plays a crucial role in ensuring that executive orders are lawful and constitutional. It has the power to review and invalidate executive orders, providing a check on the president's power to issue such orders.

Mastering the Weird 'S' in Legal Writing

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Checks and balances

The US Constitution has a set of checks and balances to ensure that no one branch of the government is more powerful than the others. While the President has the power to issue executive orders, these cannot override federal laws and statutes. Executive orders are not legislation and do not require approval from Congress. However, they must be rooted in Article II of the US Constitution or enacted by Congress in statutes.

Congress can pass a new law to override an executive order, but only for those orders enacted "pursuant to powers delegated to the President" by Congress. Congress cannot directly modify or revoke an executive order issued pursuant to powers granted exclusively to the President by the Constitution. However, Congress has used other methods to restrain executive orders, such as attempting to withhold spending on programs created by an executive order.

The judiciary also plays a role in checking executive orders. Courts can hold that an executive order is unlawful if it violates the Constitution or a federal statute. For an executive order to be invalidated, an aggrieved party must challenge the order in federal court. The Supreme Court has held that all executive orders from the President must be supported by the Constitution, whether from a clause granting specific power or by Congress.

In addition, any future President can issue a new executive order that rescinds or amends a previous one.

America's Broken Constitutional Promises: A Betrayal of Principles

You may want to see also

Historical practice

Executive orders are not explicitly defined in the US Constitution. However, they are considered an inherent aspect of presidential power, resting on historical practice, executive interpretations, and court decisions. The authority to issue executive orders is derived from the president's broad powers outlined in Article II of the Constitution, which vests executive powers in the president, and their role as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

Historically, every US president since George Washington has issued executive orders, with the first one being issued on June 8, 1789. While the form and substance of these orders have varied, they have been used to address a range of issues, including slavery during the Civil War (Abraham Lincoln), control of steel mills during a labour dispute (Harry Truman), and the Kosovo War (Bill Clinton).

The use of executive orders has evolved over time, with some presidents issuing significantly more orders than others. For example, Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a record 3,721 executive orders during his time in office, while Donald Trump issued 143 executive orders in his first 100 days, surpassing Roosevelt.

The authority of executive orders has been challenged and reviewed by the courts on several occasions. In the landmark Youngstown case in 1952, the Supreme Court struck down Truman's executive order attempting to seize control of steel mills, as it was found to exceed his constitutional powers. This set a precedent for future executive orders, with presidents becoming more cautious in citing the specific laws under which they act.

The courts have played a crucial role in upholding the rule of law and ensuring that executive orders do not violate the Constitution or federal laws. For example, during Trump's administration, several of his executive orders were challenged and temporarily blocked by federal judges, including the order to end birthright citizenship.

American Mentions in the Constitution: How Many Times?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

An executive order is a directive issued by the President of the United States that manages operations of the federal government.

The constitutional basis for executive orders is derived from Article II of the US Constitution, which vests executive powers in the President and makes them the commander-in-chief. The President is also given the responsibility to execute the laws passed by Congress.

Yes, an executive order can violate the Constitution. If an executive order violates the Constitution, it can be invalidated by a federal court.

No, the US Supreme Court has held that a President has absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for actions within their constitutional authority. However, the executive order itself would remain illegal and invalid.

Yes, an executive order can be blocked or overturned by Congress or the courts. Congress can pass a new law to override an executive order, and the courts can hold an executive order unlawful if it violates the Constitution or federal law.

![Constitutional Law: [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61R-n2y0Q8L._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Constitutional Law [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61qrQ6YZVOL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![Constitutional Law: [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/711lR4w+ZNL._AC_UL320_.jpg)

![American Constitutional Law: Powers and Liberties [Connected eBook with Study Center] (Aspen Casebook)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/612lLc9qqeL._AC_UL320_.jpg)